Author:

Caution:

Audience Rating:

Publication:

Genre:

Character Age:

TG Themes:

Other Keywords:

Permission:

I was running late, again. It’s so hard to get away from the crowd, sometimes. Everyone wants just a minute of your time, or just a quick selfie, or just a chance to shake hands. And, in a tight election, with just weeks left to go, I certainly didn’t want to offend anyone by brushing them off.

But, I also didn’t want to offend people by being late, which meant that I needed to move, now. Fortunately, I have very competent staff who make sure that happens when it needs to . . . and not before.

Portia – young, dark, intense – was my advance guard today; she was firmly taking my elbow and making apologies to the couple I was leaving. “So sorry; the governor has to be in Torvill for another event . . . thank you SO much for coming!”

The back door to the black sedan was open and I was down, Portia hopping in front to ride shotgun. My driver, Gavin, was already in gear. And off we went.

I turned my phone back on – I leave it off during events because it’s critically important that I really be present at whatever event I’m attending, rather than have my attention endlessly divided. Portia’s immediate superior, my chief of staff Dwight Evans, would most assuredly get word to me of any real emergency that I absolutely had to address. But it always amazed me – dismayed might be a better term – exactly how many not-quite earth-shattering emergencies cropped up any time my phone was off for an hour. 13 texts; I don’t even know how many emails.

But one of the texts was from Sandy, so I opened it immediately. “Sorry Sam. Need to meet you right away. Gav’s going to drop you off at Abbott Park. Cleared with Trig.”

I said, “Gav? We’re headed to the Fall Festival at Torvill, right?”

Gavin said, “Abbott Park first, boss. Just got the word from Trig.” Trigva Sorensen, aka “the Boy Wonder,” was the chief scheduler for the campaign. He always found a way for me to squeeze 26 hours of work out of an 18-hour day, bless his eager heart. But having me skip a scheduled event should have been above his pay grade.

I shot him a text. “What gives, Trig? I’m supposed to be in Torvill in 30 minutes and we’re 45 minutes out.”

The response was immediate. “A ‘how high’ moment, Governor. We’re reworking the schedule and will send to Gav & 911 when finished.” Portia purely hated Trig’s nickname for her, but it did make for a shorter text.

Well, this sounded serious, alright. Sandy wasn’t just my spouse. I made it very clear to the professionals we hired for the campaign that there was no better political mind on the planet. Sandy almost never dipped an oar into my campaigns anymore, but I told the campaign staff, on no uncertain terms: “If Sandy says jump, you ask ‘how high?’ Don’t wait to talk to me.”

But this intervention wasn’t like Sandy at all. Why not just call me? Or ask me to call? Once the calendar flipped to October in an election year, there were no spare moments for anyone. Nothing but a grueling series of 18-20 hour days, zipping between events and dialing for desperately needed campaign dollars.

We could have been anywhere in the state that day, but it happened that we weren’t all that far from home. Sandy had my schedule and would have known that. Abbott Park and the Abbott Memorial Reservoir were old stomping grounds, and the loop trail around the reservoir had left its dust on many, many pairs of my shoes. Sandy’s too. Back when we were just a couple young lawyers with a couple kids to raise. Before the local Democratic Town Committee chair had approached me to run for a slot on the town council and I had shocked everyone by winning the most votes and becoming mayor.

Life had definitely taken a turn after that. Six years as mayor, then my first state-wide race. Eight years as the hard-charging Attorney General. The last four years, Governor.

I remembered walking that loop trail with Sandy, and with little Jack, and Brittany. Brittany always wanted to drop Pooh sticks from the stone bridge over the small stream that served as an outflow. I remembered her squeals as she watched the sticks drift away, bouncing from rock to rock . . . . Seamus, the inquisitive Irish Setter, would sometimes chase the sticks, barking for the sheer fun of it.

But I honestly couldn’t remember if I’d ever taken the walk with Chase, our surprise third child. Chase had been born a bit after I started my third two-year term as mayor. By the time he was capable of walking any distance, I was spending most weekdays down at the capital. I felt guilty about that, but Sandy, as always, had picked up the slack. Without a single complaint, ever.

My trip down memory lane was interrupted by the sound of the car’s tires crunching on the gravel of the parking lot at Abbott Park. Gavin put the big beast by the entry walk, next to Sandy’s Prius. Sandy got a lot of jokes about that car.

There was no sign of Sandy, but I knew where to go. I said, “I’ll be off the grid until I get back. Shouldn’t be more than a half hour, but I’m off the grid regardless. Hold the fort, okay?”

Portia looked distinctly unhappy; Dwight was not going to approve of my disappearing into the woods without her. I imagined that Tanya Goodwin, my campaign manager, would be even less happy. Positively apoplectic, was more like it. But I had meant what I said: “How high.” I suppose it applied to me too.

I was wearing good shoes and I cursed that I hadn’t thought to have a change in the car. Presumably Sandy knew better than to be planning a hike, and a little shoe polish would hide any problems. Most days they got a lot of wear, lord knows. I went through the break in the parking lot fence and walked down the paved pathway that led through a small band of trees to the reservoir.

As I got among the trees, the paved path became carpeted with leaves – oak and ash and maple, especially maple. A kaleidoscope of reds and oranges and yellows and browns, still damp from the brief shower that had passed through the area at sunrise.

The sky was clear now, without so much as a cloud to mar the deep, deep autumn blue. I found myself, as I rarely did, wishing with all my heart that I could just spend the day walking around the reservoir, hand in hand with Sandy, discussing nothing more consequential than what we might like to have for dinner.

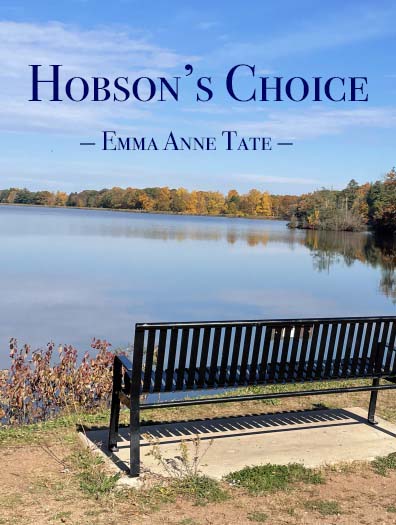

On the other side of the trees, the Abbott Memorial Reservoir opened in front of me, a breathtaking view on a clear day in early fall. Sandy was sitting on the park bench that faced the reservoir’s southern edge. Just as I expected. Looking, as usual, like an elephant perched on a footstool.

James Alexander Wilson, Jr., “Sandy” to his friends (his father having cornered the market on “Jamie”), was a mountain of a man. Six and a half feet tall, arms and legs like tree trunks and a chest like a blacksmith’s. The years had only added to his bulk. Back in the day, people had joked about how the two of us managed . . . well . . . things. Given my own, trim 5’4” frame.

I had always just smiled. The truth was, Sandy was one of those giant men who, because they have nothing to prove, are extremely gentle. The missionary position might have killed me, but there are lots of other positions. Fortunately.

For a man of his bulk, he was pretty light on his feet; he easily rose to his full height as he heard me approach, turned and smiled a welcome. “Good staff you’ve got,” he said. “Trig’s definitely a keeper.” Dangling from his thumb and forefinger were a pair of light-blue sneakers. My sneakers.

“Sandy,” I said briskly, “If you say it’s important, it’s important. But you know my schedule. Can we just talk here?”

He shook his head, “A bit too public, Sam. Better if we’re walking, in the trees.” There were other people in the immediate area, and my face was well known. But still . . . I was getting nervous. Sandy, worried about casual onlookers? Or was he worried about press people and campaign oppo types?

But this was Sandy, so I just sat down, took off my signature red pumps, donned ankle socks and laced up the sneakers. Fortunately I was wearing denim pants – it was sort of a “down-home” day for the campaign, with stops at several harvest festivals. I had put a windbreaker over my blouse and my sky-blue blazer was hanging up in the car.

Sandy took my pumps and put them neatly into a daypack. We walked off the paved area and headed out on the dirt path that looped around the reservoir. In a couple of minutes we were back under the trees. “Okay, Sandy,” I said. “Give.”

He said, “Of course, but keep walking. Like we aren’t discussing anything serious.”

I had a sudden, panicked thought that he was about to tell me that he was leaving me, or had had an affair . . . . something about his extreme caution, coupled with his apparent serenity, was freaking me out. “Fine,” I’m afraid I snapped. “I’ll walk. Just tell me what the hell is going on!”

“I forgot some papers yesterday and went home to get them. I found Chase alone in the living room, wearing a dress. Actually, dressed like a girl from head to toe. Did a nice job of it, too.” I froze and he said, very softly, “keep walking, sweetie.”

I forced myself to keep pace. “Why . . . what . . . ?” My brain was having a hard time processing.

He put a hand on my elbow, as if to guide me over some tricky footing, and kept us both moving forward. “We had kind of a long talk, as you might imagine. ’Til late at night – too late to call you. I think we now know why Chase’s grades went into a tailspin two years ago. Chase believes that he – or rather she – is female. She hasn’t wanted to say anything. Figured it might hurt you. Politically.”

I didn’t ask if Chase was certain. Almost any parent would. And, if it had been Jack or Britt, I would have asked. But Chase? If Chase said that moon rocks were made of green cheese, I’d take a healthy bite without a second’s worry for my incisors. Chase didn’t say anything unless he was certain. She was certain? Was it really “She?”

Well . . . even if “she” was certain, wasn’t it possible “she” was mistaken? “Do you think Chase is right? IS Chase transgendered?” I cringed internally at my avoidance of the pronoun.

Sandy nodded. “It was a very long talk, Sam. I wanted to be sure too. And yes, I think she is. She’s felt this way for years. With puberty coming . . . well, it’s just come to a head.”

We walked further as I processed that. Tried to adjust my mental picture of Chase, my stubborn, studious, reserved youngest child. Chase is a girl?

Sandy added, “She's right about the other thing too, you know. It will hurt you, politically. If people know.”

This time I had no trouble continuing to walk. I didn’t want to talk about the politics. I wanted, for a moment, just to be a mom. To sit with this. Try to figure out how to do this right, what it would take to be a good parent here. Life gives you moments – generally rare – that your children will remember forever. The moments they will judge you on, for the rest of their lives. What did you do, in that moment when they needed you most? In that moment when your values, and your love, were put to the test? This was, without a doubt, just that kind of moment.

But I wasn’t just a mom, and being the governor – being any sort of political figure – isn’t just a job you can leave at the end of a long day. It permeates every aspect of your life, whether you want it to or not. There was no question about my supporting Chase if – I made a mental adjustment – she had determined that she was transgendered. Support for people who are transgendered, or whose children are trangendered, has always been part of my political platform, and I had been firmly in their corner both as Attorney General and as Governor. No; my private inclination and my public positions were entirely consistent on this question.

But I could follow Sandy’s thinking without having him spell it out. The real question is, does Chase’s decision become public, and if so, when? If it became public, it wouldn’t change many people’s minds. Transphobic people weren’t going to support me anyway, and I probably wouldn’t increase my support among the trans community beyond what it was anyway.

But elections, especially in non-presidential years, are all about which people bother to show up and vote. A governor announcing on the eve of an election that one of her children was transgendered would drive voter participation through the roof – but only for her opponent. Daniel Kasten wasn’t a bigot himself, but if he needed the bigots’ votes in order to win, and he did, he knew how to pander to their darker impulses. Chase – studious, stubborn, sensitive Chase – would become a recruiting poster for the worst elements of Kasten’s base.

Worst of both worlds, there. Bad for Chase, bad for me, politically. And bad for all of the things that I had spent the last eighteen years in the public sphere fighting for. Bad for all the people who had chosen me as their standard-bearer. I was a pretty good Governor, if I do say so myself, but that wasn’t the important thing.

The tough part was that Daniel Kasten would be a truly awful governor. Including, most pertinently, on issues affecting the LGTBQ+ community. A “don’t say gay” bill and a “bathroom bill” were both part of his campaign’s platform.

“Can we keep this quiet, just for now?” I was thinking out loud. Maybe grasping at straws. Looking at the sky; at the leaves. Maybe at the trail. Looking anywhere except in the direction of my towering spouse.

“Do you mean, ‘can it be done?’ or do you mean, ‘should we do it?,’” Sandy asked.

“Let’s start with the first,” I said, “since if the answer’s ‘no,’ we don’t have to face the second.”

Sandy waggled his fingers. “Hard to say. Chase told some close friends from school. She believes they haven’t said anything. But if they have, or if they do later, then you’ll be in much, much worse shape. So will Chase, for that matter.”

I could picture it now: “noted trans advocate Governor Sam Hobson is hiding the fact that her child is trans.” That wouldn’t play well with the trans community (“are you ashamed?”), the anti-trans crowd (“anti-religion AND a hypocrite!”), or even the majority of folks for whom transgender issues were not a pressing concern. They would just peg me as dishonest, or at least, non-forthcoming. And poor Chase would think she was responsible for the whole debacle.

But . . . Chase’s friends might prove trustworthy. Chase was a sober soul; did not make friends easily. Or lightly. Maybe it wouldn’t become public. Wouldn’t that be better? Would it be right?

What did I owe the voters? It’s not like I had ever taken the position that my family life was no-one’s business. Being a working mom was most definitely part of my public persona. Pictures of me with my family, with Sandy, Jack, Britt and Seamus, and, later, with Chase, had always been included on my campaign literature. It was a way of saying, “I’m just like you; just another parent trying to make ends meet and make a better world for my kids.”

It was also a way of communicating my values. I’m a lot of people; we all are. A daughter, a sister, a lawyer, a Christian, a public official. But the thing that went on all my lit was the thing in all the world that I was the most proud of. The family that Sandy and I had made.

My current campaign website had a great picture of the five of us, shoveling snow together. We’d had a freak storm the day before the scheduled photoshoot and Tanya had said, “Perfect!” Chase – a very clearly male-looking Chase – was captured in the process of sending a snowball arcing towards Sandy. Sandy, Britt and I were leaning on our shovels, laughing; Jack – the only one of the three kids to inherit his dad’s size and strength – was the only one who seemed to be actually working.

Did the voters deserve to know that that image, so traditionally wholesome, masked a different reality that might not sit so well with some voters?

I thought about that some. In general, I thought the answer was “no.” The other members of my family were people too, and while my life has to be an open book that doesn’t mean that theirs have to be as well. They weren’t just campaign props.

But if we were doing the website today, would I include a family photo? I would. And if Chase wanted to present as a female in the photo, I would support her. But suppose she said, “no, let me look like a guy in the photo, even though I’m not?” Would I be okay with that?

No, I thought. I wouldn’t. I wouldn’t deliberately obfuscate what I knew to be true, for “political expediency.” Which is just a fancy way of saying, “trying to get people to vote for you based on misconceptions that you deliberately fostered.”

“What are you thinking?,” Sandy asked. I guess I’d been lost in thought for a while. We were well past the point in the trail where it starts climbing up to a ridge overlooking the reservoir.

“I’m going in circles,” I confessed. “If we’d known six months ago, we’d probably simply have done what any sympathetic parents would have done, and when the story surfaced, we’d have put out a statement saying we were supporting Chase’s decision and didn’t intend to address it further. If we were lucky, it would be old news by now. Certainly it wouldn’t drive turn-out like it will this late.”

We walked another thirty yards or so before I added, “If we’d known a year ago, maybe . . . I don’t know. Maybe I wouldn’t have run again. We could have dealt with this as a family, without the public spotlight.”

“Absentee ballots have already gone out,” Sandy said. “Your name’s on the ballot even if you drop dead tomorrow. And anyway – Robotman couldn’t win this thing.”

Rob Ottman, the running mate who had been foisted on me by the party poobahs, might as well have been a robot for all the charisma he displayed. Except that no-one would build a robot with such an underpowered CPU.

“I know,” I sighed. I could lose this election, even without this new complication. But it was clear to all of us, the poobahs very much included, that in the current political environment we didn’t have anyone who had a better chance.

We walked on in the silence of our own thoughts, hearing the gentle sound of the wind rustling the leaves, pulling them from the life-giving branches, scattering them in swirls of random color. The air smelled sweet, clean. Why couldn’t life be as beautiful, as simple, as a walk through the woods in a morning in October?

“Let me ask you this,” Sandy said. “If it were just the election, if you didn’t have to think about the firestorm that will hit Chase, what would you do?”

I thought about it. It didn’t take me long. “I’d go public. God, I want to beat that bastard Kasten like he was a five-gallon bucket on a city street corner. But I’m not ashamed of Chase, and I wouldn't want anyone to think I was. If it’s she, it’s she.”

“Even if you knew it would cost you the election?,” Sandy pressed.

I stopped, forcing him to stop as well, a bit short of the crest of the rise. “You taught me better than that, love,” I said. “The voters get to decide whether I stay on the job. I’m just supposed to make sure they have the information they need to make the choice.”

His soft smile was a communion of sorts – a deep sharing of years and years of memories. Of hard-won battles, fought side-by-side. Three municipal campaigns; he’d run the first two. After that, he faded into the background, my frequent absences making his presence at home with the kids all the more critical.

But the imprint of his character was on every subsequent effort, even the state campaigns where I had the high-priced talent. The operatives whose only asset was their favorable win-loss ratio. Sandy had more integrity, more faith in democracy, than all the political operatives combined. I was the public face, but it was very much our political career.

“So, yeah,” I said. “I’d still go public. Even if I knew I’d end my career, that bastard would get my office, and he would do his damndest to undo all the good we accomplished. Because if that’s what the voters want, that’s what they get.”

“Okay,” Sandy said. “So then, the only question is what’s best for Chase?”

“Yes,” I said. “Like it should be. And I’m torn there. I need her to know I support her. That I’m not ashamed of her. If we try to keep it quiet, after she’s told you, all the nice words won’t matter. She’ll think I’m ashamed. She’ll think all my public support for trans rights was a sham. But on the other hand . . . .” I stopped. The other hand was, after all, pretty grim.

“They’ll tear her apart,” Sandy summarized. “Dan Kasten’s crew won’t give a shit about what they might be doing to a fourteen-year-old. She will be the poster-child for everything that’s wrong with the ‘liberal elites.’”

I nodded miserably. “I know,” I said. “I know.”

Sandy reached up and laid one of his massive palms against my cheek, wiping the single tear drop that had escaped my burning eyes. “So does she, love,” he said softly. “Maybe it’s time to bring her into this conversation.”

I opened my mouth to begin a question, but saw the answer already in his understanding eyes. I knew where she was. “Yeah,” I said. “Let’s go talk to our daughter.”

I took Sandy’s hand and we walked fifty yards further, to where the trail hit the crest and leveled out. There, I well remembered, was a quiet bench overlooking the reservoir, a little lawn, and the spreading branches of a mighty sugar maple.

We had sat together on that bench, Sandy and I, fifteen years ago, on a day much like this one. Jack was high in the branches of the tree; Britt was chasing Seamus, Seamus was chasing his frisbee and we . . . we were alive and in love and chasing our dreams. And I had told my wonderful man, in the privacy provided by the kid’s temporary distraction, that he was going to be a father again. Our last child, though we hadn’t known that then.

And there she was, sitting on that same park bench, dressed appropriately for a walk in the autumn woods – sneakers, capris and a cute sweater. Sensible makeup, of course. Subdued nail polish. Chase would have spent hours of study figuring out what was appropriate and would never look over the top or garish.

Chase had deep-set, warm, expressive eyes that revealed a sensitive nature. She turned those eyes towards us as we emerged from the trees, seeing Sandy first – of course – but then finding me and watching closely, anxious to see my reaction. Afraid of rejection, certainly. But also afraid of what this all might mean for me, for everything I had worked for. Everything we had worked for.

But the stubborn was there too, thank God, in the set of her jaw. She would need that. My studious, stubborn, wonderful youngest child.

My daughter.

I opened my arms as wide as I could, picked up my feet and ran to meet her.

— The End

For information about my other stories, please check out my author's page.

If you liked this post, you can leave a comment and/or a kudos!

Click the Thumbs Up! button below to leave the author a kudos:

And please, remember to comment, too! Thanks.

Comments

So good

Thanks for an excellent story.

Hus,

Erin

= Give everyone the benefit of the doubt because certainty is a fragile thing that can be shattered by one overlooked fact.

Thanks, Erin.

Hugs to you as well.

— Emma

Just the caution was worth a kudos

Said without any intention of diminishing the sweet story.

That helps answer a question . . .

I did wonder whether people read the cautions . . . . :)

— Emma

Between the devil and the deep blue sea

Of course Hobson's Choice is synonymous with no choice at all. Your mastery of the English language is seemingly bottomless. What is ironic to me is that you chose two of the most, in my opinion, despicable professions to put on the horns of this dilemma. I am so glad that even two lawyers can set aside all the machinations and simply put their child first. Thank you for this treat Emma. (and sorry for going dark on you, I have family issues of my own I'm dealing with)

P.S. And to slightly paraphrase the immortal words of Lt. Col. Frank Slade in one of my most favorite movies scenes from 'Scent of a Woman' "Her soul is intact! It is not for sale!) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TuYhfCkRxyE

DeeDee

Thank-you Dee!

So good to hear from you, and so glad you enjoyed the story! I think your Slade paraphrase is appropriate: it IS easier for politicians and lawyers to lose their souls compared to many other professions. In part it’s a power thing, but in part it has to do with being responsible to, and often for, so many others. I’ve tried to show a bit of that dynamic here.

— Emma

I'm not crying, you're crying...

Beautiful, and as well-written as your other stories. (I LOVED Aria for Cami.)

Thank-you, Lisa

So glad you enjoyed both this and Aria!

— Emma

Yes, the haters ...

... will come out in force, but so might the lovers. Give the people the benefit of the doubt until they prove otherwise.

BE a lady!

From your keyboard. . .

To God’s inbox. Thanks, Jezzi.

— Emma

Politician with integrity

Truly a rare and endangered species, possibly even mythical now like Unicorns and Dragons.

I have really soured on US democracy over the years. The mythical common wisdom people are supposed to have seem to have disintegrated with social media, as so many just vote with their old hatreds instead of their compassion.

As said, the voters against her will just get what their bigotry will get them.

However bad it may be . . . .

We would miss democracy sorely were we to lose it. But don’t give up heart. However rare, our current crisis has included examples of tremendous integrity and courage.

— Emma

love to see this one continue

very nice !

Thanks, Dot

I wrote this one as a solo, so I don’t have any thoughts about a sequel. Of course, if a storyline just pops out of a dark alley and mugs me while I was minding my own business— which is how MOST of my stories start — I’ll certainly write it down!

— Emma

Dear Reader...

Miss Tate, it's a beautiful story about a parent's love for her own child over everything else. Two lawyers will survive the fallout even if the Gov doesn't survive the election. The question is, how many lives won't survive if DirtBag gets elected instead? Not a fan of stories without a ribbon on the ending but this one is so thought provoking it's acceptable.

Hugs Emma

Barb

We thought we would change the world until the challenge became more than we could bare.

Oklahoma born and raised cowgirl

Thanks, Barb

Yeah, I don’t have answers on this one. The best I could manage was to explore the questions.

— Emma

Warning: lawyers with integrity

This reminded me of an essay “Why I Defend Guilty Clients” from Harper’s Magazine. About 1990; certainly between 1987 and 1993 as I remember the room where I read it. It was a very different piece of writing but also carrying elemental truth.

In an adversarial justice system. . . .

Lawyers with integrity almost have to adopt “rule utilitarianism” as a philosophy. It’s logical, but often emotionally unsatisfactory.

— Emma

Duplicate comment

Oops

— Emma

Looked it up

Good read! Looks like it was the Dec 1986 issue. Harper's has it behind their paywall here, but someone has it posted over here.

Decisions

Determine who you are and what you will be...

They do indeed.

And sometimes they have other effects that rippLe across a lot of other lives too.

— Emma

Our Adversarial System

Gives lawyers and politicians no encouragement to be ethical.

This story demonstrates that some things cannot be set aside in the pursuit of power. How I wish real life was really like this.

There are good people, even in those positions.

I have known some.

— Emma

All Politicians Are Narcicists

. . .except those few who aren't.

I've spent the last two days reading Michael Cohen's book "Revenge." The book is filled with anecdotal evidence that elected officials are capable of extreme evil.

One of my business partners had been an AG and then Governor. He's one of the most ethical persons I know.

Your story rang true. I could see my friend go through the mental gymnastics in your story. He actually refused to live in the governor's mansion because if he did his kids would have had to switch high schools. The Democrats made a lot of that saying he thought he was "too good for the governor's mansion."

Congratulations on an excellent story.

Jill

Angela Rasch (Jill M I)

Thank you, Jill.

Given all the bad stories we see in the news, it’s hard not to get cynical. But if we want things to get better, we have to work on figuring out who the good people are, and support them.

— Emma

Very good

Great title, so very apt. I'm so glad I don't have to make decisions on these kinds of things but it is so good of you to present this because it seems likely somebody does.

>>> Kay

Thanks, Kay.

I’m glad you enjoyed the story!

— Emma

Yet another superb short story

…in which you demonstrate your talent for different tones, styles and themes.

You should maybe think about anthologising them and publishing them on Amazon, because both they, and you, deserve a wider audience.

Rob xx

☠️

Thank you, Robert

But I really like the company here. :D

— Emma

Awww

Very sweet story.

Why is my room so dusty?

Thanks, Jennifer

So glad you enjoyed it!

— Emma

You've done it again!

I keep trying to catch up on my reading, working up the list by date - oldest first - then you come up with another story and I have to jump to the top and read that first! There are other writers that I do this for, but it's very bad for my self-discipline :)

Anyway, another excellent story - who would have guessed that lawyers / politicians actually had principles!

Alison

The nice thing about self-discipline. . . .

Is that you can always tell it to sod off without offending anyone. :D Glad you liked the story, Alison!

— Emma

I really like your writing

and have right from the first, where you appeared fully formed on the scene, like Athena from Zeus's headache.

The ending was perfect (and more may have been hinted from the title). I am content to leave it like that, after all, it is YOUR story.

On the other hand, if you decide to resurrect the family at sometime in the future, with a change of viewpoint or whatever, I will be delighted to read more. Your governor character is a marvellous concept -- if only real life could produce more (politicians) like her!

Best wishes

Dave

Thanks, Dave!

So very kind of you. As far as the good governors go, a wise man once said that the cream AND the crap tend to rise to the top.

— Emma

Brilliant story...

Should come with a warning that tissues may be needed. Your skill as a writer and teller of stories - impeccable. Loved this offering...

XOXO

Rachel

XOXOXO

Rachel M. Moore...

Thank you, Rachel

You’ve got me blushing! :D

— Emma

It was there as the random choice

I must confess, I couldn't remember the details, so I read it again.

Recollection struck in, but I continued, and after completing it, I wiped my eyes and checked the comments. There was mine, from the first reading. The second reading moved me even more deeply.

At the risk of seeming repetitive, Thank you again!

Dave

Gotta love the random choice feature!

I’ve caught some really great stories that way. I’m delighted to know that this story held up well on a second reading. Thanks, Dave!

— Emma

The Wrath of Khan

I'm reminded of the climatic scene. "The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few, or the one." How many are sacrificed on the alter of idealism? Are they necessary sacrifices, or unavoidable collateral damage?

What do you do when all the choices are bad? From the song Free Will, "If you choose not to decide you still have made a choice." A friend of mine used to say that when all the possible results are equally bad it frees you to make the right choice and to hell with the fallout.

I dunno.

They know they can survive

If only

If only the machines of politics and power didn't make it darn near impossible (on both sides of the so-called aisle) for those with integrity to succeed. Lying, obfuscating, pandering - sadly in the newsbites and contrived news cycles even those who DO have integrity will be portrayed as the opposite.

I find it disgusting that it doesn't matter which news outlet I read, the slant/spin/smear is horribly apparent. Truth used to be found in between, but that between has vanished with the similarities of the extremes which have managed to take over.

All that said, it's a lovely story, Emma, and an illustrative one.

Thank you, Erisian!

I do know people in the public sphere who have incredible integrity. I know some good news sources too, though finding them takes work, for sure!

— Emma

This story

Touched me in many ways. You have a career mom, and a stay at home dad. The mothers career is often one that most people look on with distain and mistrust. But you can tell she doing her best to make it work and to honest about it. The dad is willing to step aside and let his wife have the limelight. And then you have Chase, a young woman struggling to find herself. Who is wise beyond her years, who is at odds with herself and at odd's with the currents of her soul. The ending is sweet, but leaves us wanting more. Another wonderful piece of fiction. You are a true wordsmith.

Relationships

I started this one with the intent of exploring coming out issues through the lens of our crazy current culture war politics. But as usual, I found the relationships between the characters, especially between Sam and Sandy, became the true heart of the story. I can’t help myself; ideas fascinate me, but relationships touch me. Move me. Make me cry, even when the characters are fictional. I wrote this, so obviously I know what’s coming. But Sam’s recollection of the day she told Sandy she was pregnant with Chase makes me cry. Every. Damned. Time.

Thanks, Sunflower— so glad you read and enjoyed it. Oh, and . . . there is a bit more out there. ;-)

— Emma

So many factors

but just one choice. I pray i get this right.

Faith that God would honor Sam's decision but would the voters understand? Would God sustain her and her family regardless of any outcome? How would she campaign knowing what opposition she would surely face? Would she withhold the truth to assure a better outcome in service to those like Chase? Like us? In the long run? Would she this...would she that... What if this? What if that?

But in the end, which really was there, was there all along at the beginning. It was all about a mother's love. First, last, and always, her faith was in her daughter. Her love was the best and only real factor in her choice! No matter what, it's all about who is important.

The last words my mother ever said to me were, "I love you with all my heart." I've been thinking and even writing an awful lot lately about mothers and their love. Sam loves Chase with every part of her being!

You, dear woman, have given me a feast for thought. Thank you!

Love, Andrea Lena

Thank you, Drea.

Your comments are always so full of thought and wisdom. Hard-earned wisdom, I know. The thing I particularly love about Sam in this story is how well she knows her youngest child as an individual. Had it been one of her other children, she would have questioned whether it was a phase they were going through or if they were sure. But she knew Chase was deeply serious and completely honest. So Chase said she was trans, Sam had a lot of trust in that.

Thank you for the kind comment!

— Emma

Heartwarming.

Heartwarming.

Thank you, once more!

Everyone deserves parents like these!

— Emma

This is my second time reading this

I couldn't resist stepping in and acting as Sam's press secretary.

Press Release:

Ladies and gentlemen, thank you for coming on such short notice. Yesterday, I was made aware of something that that will test me personally, politically and morally. It will test my resolve to my stated, long held political position and morally in that I will have to stand by my personal convictions publicly. Copies of this release will be handed to you as you leave. I would ask that you quote it, or in the case of broadcast journalists, read it in its entirety verbatim. It will be short.

It’s in the final hours of my gubernatorial campaign and I assure you that this is not some well thought-out political strategy. Quite the opposite. I reveal this information, involving a member of my immediate family reluctantly, but rather in deference honoring my stance on full discovery in my campaign.

My husband informed me that two days ago he became aware that my youngest child is transgender. We have discussed it at length with her and are in contact with a gender specialist as to the best practice course for her. It will be our top priority to support her in her journey and will not allow her to become a political football.

I will not now nor in the future answer any questions regarding this as it would be an invasion of her personal life for me to discuss this beyond this announcement.

Thank you again for coming and in advance for your cooperation.

Hugs

Patricia

Happiness is being all dressed up and HAVING some place to go.

Semper in femineo gerunt

Ich bin ein femininer Mann

I read this one before but didn’t comment.

It’s a good story and really sets up the moral dilemma. Unfortunately too many politicians get their ethical compass diverted by the demands of their office.

We’re about to find out what happens when the other person wins. A lot of people who voted for Biden 4 years ago just didn’t show up. It probably would have taken more than one interview answer to bring them out in force. But I know our country needs leaders who actually stand for something. And my state is going to pick a new governor this year.

Gillian Cairns

I’m afraid so.

The voters had a clearer choice this year than in any election in my lifetime. I think they chose poorly, but it’s a democracy and the choice is theirs to make. The days that come will be hard for many, including our community but not limited to it.

— Dan Hill, Hold On

— Emma