|

GOODBYE MASTER STOKES

CHAPTER 1: TEMPUS FUGIT By Touch the Light You’re being stupid, I told myself. Plug had made all that up. If Testranol had those kinds of side-effects and they’d been exposed on national television, how was it that nothing had appeared in the papers? Why hadn’t the people who’d manufactured the drug been publicly disgraced? |

Okay, it's another period piece. Anything to avoid mobile phones and the bloody Internet!

To get into the feel of it just hum Rod Stewart's 'Maggie May' or Jethro Tull's 'Life's A Long Song', or if you're really -and I mean really - cool, Family's 'In My Own Time'.

You may think I'm wasting my time

Say what you think, you know I don't mind

I SUPPOSE I'D BETTER ADD A DISCLAIMER

The medical condition described in this story is the product of my imagination. There was indeed a drug that some expectant mothers took in the 1950s and 1960s which in a few extreme cases resulted in girl babies being mistakenly identified as boys, but to the best of my knowledge the condition didn't persist until adolescence. Any resemblance between the product named here as 'Testranol' and an existing drug is entirely coincidental.

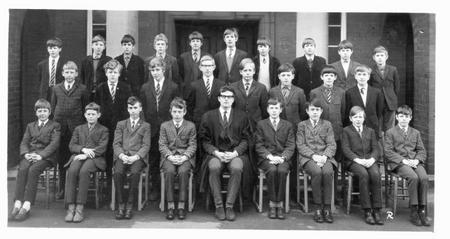

One more thing: this chapter is dedicated to the memory of the late John Oscar Coxon, who taught me History at Hartlepool Grammar School in the early 1970s. His enthusiasm for the subject and his ability to put it across were inspirational, and I am proud to have been a colleague of his during the final years of his career.

CHAPTER 1: TEMPUS FUGIT

October 21st 1971

When Pansy Porter fainted ten minutes before the end of Chipper Wood’s Maths lesson, and we all saw the vivid red smear he left behind as he slid from his chair, there was uproar.

Chipper had difficulty keeping order at the best of times; now he lost control completely.

“Pansy’s having a period! Pansy’s having a period!” we chanted. Desk lids were banged. Pens, pencils, rulers, set squares and protractors went flying across the classroom. Gungies splattered on the blackboard and the wall behind it.

Then Oscar Collings walked in, and within seconds you could have heard a microbe burp.

Bull-chinned and bearded, he swept his uncompromising gaze across every face like a searchlight. It paused as it illuminated Pansy’s slumped shoulders and lolling head, but not for long.

“Chisholm, go to the secretary’s office and tell them to call the nurse,” he instructed the boy nearest the door, each syllable he enunciated demanding your absolute and unwavering attention. “The rest of you…RAFFERTY!”

Oscar took a single step towards the thin, weasel-faced figure at the back of the room. One more and there might have been another, browner smudge for the caretaker to wipe up.

“W…w…what, sir?”

“You must have a very limited understanding of the laws that govern the propagation of light, Rafferty, if you thought I would be unable to see you sniggering.”

“No sir…I…I mean yes sir.”

“You will collect your things, leave the room in single file and gather in the south cloister,” Oscar told the class. “And you will do this in silence.”

He didn’t say what would happen if we disobeyed him. He didn’t have to.

‘Cloister’ was a rather grandiloquent term for the open-sided brick passageway that led from the west wing to the assembly hall, but then Newburn Grammar School had always fancied itself a cut above other establishments of its kind. Many of the masters had graduated from Cambridge; some had dined there at high table. Former pupils had gone on to represent their country at rugby and cricket, to forge successful careers as doctors, solicitors and high-ranking civil servants. One had recently been appointed Sub Dean and Canon Precentor at Durham Cathedral.

I had no such hopes for myself. I was bright enough — too clever for my own good, mum often complained — but I didn’t live behind the park, I wasn’t much use in a scrum, I couldn’t hit a six and I lacked the confidence to break free of the herd mentality that infected all but the affluent elite and discouraged academic excellence in favour of getting along by keeping your head down.

“Here he is!” someone hissed, and the murmuring we’d allowed ourselves to indulge in while Oscar was out of earshot ceased.

“Look over to your left,” he boomed, gesturing with a gowned arm across the car park to the cricket lawn and the belt of woodland that enfolded it. “You will notice that much of the ground is thickly carpeted with leaves. That is because the trees, being of the deciduous variety, are letting them fall. Your O level year is upon you, gentlemen, and it is passing. To imprint this simple concept into the grey matter beneath your skulls, you will all write the following line from Virgil two hundred times: Sed fugit interea, fugit inreparabile tempus.”

“Yer doin’ mine for us, Rafferty,” growled Briggsy.

“Yer can do mine an’ all,” muttered Kendo, not to be outshone.

Rafferty paled but didn’t argue. He was desperate to hang around with the hardest lads in the Fifth Year, even if it meant being treated as a virtual slave. Maybe he imagined that some of their toughness would eventually rub off on him.

Oscar directed us to hand in our work tomorrow morning at break. At this point most teachers would have taken a register so that no one could claim he was absent when the punishment was meted out. Not him; he’d counted twenty-six of us and that was how many sets of lines he would receive.

The dinner bell went and we were dismissed.

“Stokesy…Stokesy!” I turned to find Rafferty offering me a dog-eared scrap of paper torn from an exercise book — no doubt it was intended as the raw material for more gungies — and a chewed pencil. “Write it down for us, will yer?”

“Piss off! I’ve already got to do it two hundred times. Might only have been one hundred if you’d managed to control yourself.”

“Aw, come on Pete! If I get it wrong they’ll knack us.”

“Don’t you remember it from First Year?”

“I wasn’t ‘ere then, was I?”

So the phrase hadn’t been drummed into his brain by a Classics master who believed that learning random quotations from a dead language by heart was an essential part of an eleven year old boy’s preparation for adult life.

“All right,” I sighed. “But you can do the writing. I know where that pencil’s been.”

I recited the phrase for him, becoming increasingly impatient as he struggled with the word inreparabile. Our year were on first sitting this week, and if I was late I could expect a spoon in the forehead from the prefect in charge of the table.

“What’s it in English?” Rafferty asked me once he’d covered the paper with his scrawl.

“But meanwhile it’s flying, time is irretrievably flying.”

He traced the words with his finger, shaking his head.

“Fuck it,” he laughed, then took off after Briggsy and Kendo.

Picking up my haversack, I hurried out of the cloister and along the west wing’s bottom corridor towards the top yard and the well-trodden path through the woods that led to the new dining hall, erected in the spring as the first part of a development that would eventually include a swimming baths and a sports centre. On the way I caught up with Plug and Gash, who were both in a higher Maths set than me and would take their O levels in that subject before Christmas, giving them one less exam to worry about next summer.

“Have you heard about Pansy?” I asked them.

“Yeah, Teeth told us,” said Plug, whose nickname arose not because he was ugly — though we all agreed that he was — but on account of Mr & Mrs Graydon’s failure to realise how their son Philip’s initials would appear if they gave him middle names as pretentious as Leo and Unwin.

“Wish I’d been there,” chuckled Gash.

“Then you’d have got two hundred lines from Oscar,” I pointed out.

“Be funny if it really was a period,” laughed Plug.

“Yer fuckin’ daft or what?” said Gash. “How could it be a period?”

“He might be one of them, er…”

“He’s one of them all right!” I tossed in, feeling a twinge of guilt because I’d once been best mates with Pansy — though that was when everyone still called him Paul.

“Naw, what I was goin’ to say was he might be one of them I dunno what yer call ‘em but there was this documentary on not so long back where there were these kids who had what looked like cocks but they weren’t.”

“What the fuck were they then?” asked Gash.

“Some girly bit that grew bigger than it should’ve done.”

“Yer takin’ the piss, aren’ yer?”

“I’m not!” insisted Plug. “It was this stuff the mothers took to keep ‘em from losin’ the baby ‘alfway through. It made the kids look like lads on the outside, but on the inside they’ve got all lasses’ bits.”

“What ‘appened to ‘em?”

“They waited till they started needin’ jam rags, then they give ‘em these pills that turned ‘em into proper girls.”

“How’d they work? Make it shrivel up an’ go back in?”

“Must do. Anyway, they all got sent to this special school so they could be taught ‘ow to wear dresses an’ everything.”

“Jesus!” cried Gash. “I’d ‘ave sliced me fuckin’ wrists open!”

“I think I would an’ all,” said Plug.

“Me too,” I concurred.

But I didn’t contribute anything else to this conversation. I was so deep in thought that it washed right over my head.

Because I’d remembered someone saying years ago that between giving birth to Jeanette and me, mum had suffered four miscarriages.

And that I might have been the victim of a fifth were it not for a drug called Testranol.

As Newburn Grammar School was located on the south-western outskirts of the town and we lived on the very northern edge of the built-up area, it usually took me about three-quarters of an hour to walk home. I only caught the bus in the direst weather; not only did it have the main shopping area to negotiate, which meant it hardly saved me any time at all, but four new pence a day added up to three quid over the course of a term, enough and to spare for the Jethro Tull LP I needed to complete my collection.

The most interesting section of the journey was right at the beginning. The school stood on a high terrace overlooking the stream after which the town was named; here, about a mile and a half from the sands where the water spread into hundreds of rivulets as it emptied into Cleveland Bay, the burn flowed through a long, narrow open space set out with tidy rock gardens, secluded bowers reached by winding pathways, and grassy slopes interrupted by scattered stands of trees. This was followed by a succession of dull inner suburban streets and avenues, the monotony of the route broken only by the occasional main road that crossed it heading in a dead straight line for the town centre. Often I would try to make it seem shorter by dividing it into stages and counting each one off as I completed it, or pass the time by humming my favourite tunes and using them to create daydreams in which I was the performer and Lisa Middleton my audience, her eyes shining with joy when she began to realise that every song was especially for her.

Today I had no need of such strategies. Pansy Porter’s fainting fit had given me plenty to occupy my mind.

I’d begun evaluating the evidence during Scripture, and it was suggesting some pretty disturbing possibilities. First of all there was my physique to consider: I was slightly smaller and less robustly built than most of my contemporaries, and despite enjoying a normal, active lifestyle my arm and chest muscles were as poorly developed as they’d been when I was in junior school. I hadn’t started shaving yet; the bum fluff that had appeared on my chin a few months ago was a fading memory. My voice had deepened, but not to the extent that it could be mistaken for a young adult’s. Most worrying of all, only the finest down, so sparse it was practically invisible even when I peered closely at it, had ever sprouted from my legs.

On the other hand, I had a sixteen year old boy’s interests and urges. I watched every home game at Clarence Park. I pestered my dad for a moped. I read adventure stories and Science Fiction. I listened to rock music. I’d grown my light brown hair fashionably long. I joined in when my mates organised kickabouts in West Park, and when they bought bottles of Newcastle Brown Ale from the off-door on Thornhill Road and sat on Cameron Bank to swig from them.

And I was in love with Lisa. That clinched it.

Or it might have done if I’d felt the slightest stirrings of lust for her.

You’re being stupid, I told myself. Plug had made all that up. If Testranol had those kinds of side-effects and they’d been exposed on national television, how was it that nothing had appeared in the papers? Why hadn’t the people who’d manufactured the drug been publicly disgraced?

I was still debating the pros and cons when I passed the cemetery gates on Jessamine Road. My long trek was nearly over; another minute or two and I’d be at the crossroads where you could look past the allotment gardens to the fields belonging to Throston Grange and Middle Warren farms, just yards from the quiet cul-de-sac which was the only home I’d known.

Then I saw Lisa. She was on the other side, walking past Jezzie Jailhouse — otherwise known as Jessamine Road Primary School — so I didn’t get the chance to find out if she’d return my smile again, but that scarcely mattered. My mental images of the flame-red hair she’d had cut short on top but at the sides and back still hung almost to her shoulders, the heart-shaped face with the nose that was just a little too aquiline, the denim jacket, the flared jeans and the platform shoes, all of them would now be refreshed. Tonight they’d help me imagine whole worlds which just the two of us would inhabit; Martians might invade, flood, fire, pestilence and even nuclear war might threaten, but Peter Stokes would be there to keep her safe and warm.

First he had homework to do — and two hundred lines to write.

Ashleigh Close was a hotchpotch of 1930s semi-detached houses and short terraces put up the decade before. Number 21 was in the middle of one of the latter, on the left-hand side as you walked towards the uncultivated ground at the northern end. It had a small hedge-fronted palisade, a low wrought-iron gate, a curved bay window and a doorbell that mimicked the chimes of Big Ben. A humble dwelling, to be sure: there was no central heating, you could only reach the bathroom by squeezing around the table that took up most of the space in the dining room, and the lavatory was an extension the size of a pantry built onto the kitchen. But the back garden made up for these deficiencies, and if I no longer courted my parents’ wrath by climbing the apple tree, or needed to escape that of my big sister by hiding among the fuchsia bushes, it continued to be a place where I could practise keepie-uppie, or hurl a tennis ball against the wall of the shed and see how many times out of a hundred I could catch it. All things considered, I could have grown up in far less pleasant surroundings.

The staircase rose straight from the vestibule, so I’d acquired the habit of rushing up to my room, dumping my haversack on the bed, unfastening my tie and throwing it to the floor, then exchanging my grey flannel trousers for a pair of jeans or cords and my shoes for slippers before I did anything else.

And you could tell it was a boy’s room. In the three and a half years since Jeanette had bequeathed it to me by leaving to get married I’d concealed the teddy-bear wallpaper with posters of football squads, rock bands — Sonia Kristina, lead singer with Curved Air, took pride of place — astronauts, comic-book heroes, steam locomotives and spectacular photographs of volcanic eruptions, ferocious wild animals and star-filled night skies. The shelves creaked under the weight of model aircraft, battleships and tanks. Few of the discs strewn around the record player were in their sleeves, fewer still of the shirts, jackets and jumpers in the wardrobe were accorded the dignity of hanging from a rail.

I didn’t plan to spend much time there this evening. It hadn’t been a bad day for the third week in October, yet as the light began to weaken I sensed a chill in the air that the two-bar electric fire would struggle to stave off. I’d have to finish my lines before I went downstairs, otherwise there’d be an inquest I was in no mood to tolerate; the ten ‘quickies’ Sidlet had given us at the end of French and the essay on the causes of the Russian revolution could be done in the front room while I waited for Top of the Pops to come on.

I lifted one of the dozen or so spare exercise books from the pile in the corner — it was easy enough to con the more absent-minded of the masters into giving you a new one, in the Third Year I’d done it twice in one lesson with Pop Sherman — and ripped two double pages from the middle.

Sed fugit interea, fugit inreparabile tempus.

But meanwhile it’s flying, time is irretrievably flying.

As I began to write, setting down all the Seds first to get them out of the way, I had no idea how turbulent that flight was soon to become.

Tea on Thursdays was mum’s chance to experiment, since dad always went to the Labour Club after he left the office and got fed there during the meeting. Sadly the results of her explorations into the realm of foreign cuisine rarely met with success, and tonight was no exception. Although there may indeed have existed parts of the world where cod fillets were coated in breadcrumbs, fried and served with tinned sweetcorn and plain boiled rice, I felt certain that the natives would have come up with something rather more appealing to accompany these delicacies than parsley sauce.

That was as unconventional as it got. The meal didn’t begin until mum had turned off the radio and said grace in dad’s absence; she’d been raised to believe that table manners should be enforced with a severity that would have caught Mrs Beeton out, and showed no signs of mellowing as the years went by. Woe betide Peter Stokes if he should talk while his mouth was full, leave food on the end of his fork, or fail to ask permission before he rose from his chair.

“I want you to run round to your gran’s,” she said in her warm Berkshire accent as we started clearing up. “There’s a pile of magazines on the telephone table, and some books I brought back from the shop.”

“Shall I go now?”

“After we’ve done the washing up.”

It had been worth a try.

The burden I lugged through the front door twenty minutes later was a hefty one, but I didn’t have to take it very far, just to the street that began at the corner of the school. In fact ‘gran’s’ was a misnomer, as she’d died fifteen months ago; the house now belonged to her youngest daughter, my aunt Rachel.

Rachel had a past, which made her unique in the Stokes family. Not that I knew anything about it. How could I, when my polite enquiries as to the identity of the fetching young beauty whose sepia-tinted portrait she kept on the mantelpiece beside uncle Bob’s were consistently answered by my parents with a curt “we’ll tell you when you’re older”?

It was the same with the facts of life. I’d worked out for myself that babies grew inside their mothers’ tummies, but if it hadn’t been for the copy of the Kama Sutra Gash pulled out on the school field one dinnertime I’d never have guessed in a million years what put them there.

All the front doors on Everard Street opened directly onto the pavement. The houses had only one main downstairs room, and back yards instead of gardens. Until I was six or seven a huge tin bath had hung from a nail hammered into the side of the toilet shed; dad had told me that on Sunday evenings gran would boil pan after pan of water to fill it, he and his brothers taking their turn to bathe first and then being sent to bed so they couldn’t watch their sisters undressing. My grandparents must have been remarkable people to bring up eight children in a building this size.

I went in without knocking, and found my aunt in the armchair watching the regional news. She remained a handsome woman, even if by her own admission she was ‘getting on a bit’. I sometimes felt sad that she’d spent so long looking after gran instead of marrying again. Now it looked as if she was destined to drift into old age alone.

“Hiya,” I said. “Where d’you want these?”

“Leave ‘em on the table, love. If you want to help yourself to a drink or a biscuit…”

“No thanks. Just had my tea.”

I took off my anorak and sat in the chair opposite hers. It was the first act in a ritual I hoped would end with her twisting open her purse and giving me a shiny 10p piece.

“How’s school goin’?” she asked, fiddling with the long necklaces she always wore.

“Not so bad. We break up for half-term tomorrow.”

“Is it tatie-pickin’ week already? Doesn’t time fly! It only seems like yesterday when you were in short trousers.” Her eyes narrowed. “Is everything else all right?”

“What d’you mean?”

“You haven’t had any aches or pains lately?”

“Only the bruise I got the other morning when I banged my elbow on a lamp post trying to avoid stepping in a lump of dog dirt.”

“No tenderness anywhere?”

“I don’t think so…”

“You don’t feel tense or angry or bad-tempered?”

This wasn’t in the litany. By now she ought to have been entertaining me with amusing anecdotes about my early childhood, such as the time mum left me in the pushchair outside Timothy Whites and came back to find it surrounded by people listening to me belt out ‘Tulips From Amsterdam’, or when she was berated by the headmistress during my first week in infant school for teaching me to read when in fact I’d taken care of that inconsequential little task myself.

“I’m fine, honestly!”

“Are you sure? If you’re unhappy about anything you can tell me, you know. It won’t get back to your mother and father.”

I wanted to tell her I’d come here to deliver a bundle of magazines and books, not be grilled about my private life. But I needed that 10p, and the only way to coax it into my jeans pocket was to play along.

“Okay, there is someone on my mind,” I confessed.

My aunt leaned forward.

“Who is it?”

“I’d rather not say.”

She rested her forearms on her thighs. Her expression was a blend of deep curiosity and genuine concern.

“Is it a boy?”

“What?”

“This person you keep thinking about. Is it a boy?”

“No!” I laughed. “No, it isn’t!”

“Are you tellin’ me the truth?”

“Of course I am!”

“There’s nothing wrong with havin’ feelings, Peter. You can’t help who you fall in love with.”

I saw her eyes dart to the portrait on the mantelpiece, and suddenly it made sense.

But I was too shocked to say anything. I knew what a poof was; it had never occurred to me that women might fancy each other. And here was my dad’s sister looking at a picture of a young woman who’d once been her girlfriend…

“I…I’m not, you know…” I forced through my lips eventually.

“So what’s she called?”

My heart sank as I realised that I’d painted myself into a corner. Lisa lived half a dozen doors up from my aunt, who I gathered was on friendly terms with her parents. To make a clean breast of my emotional attachment to a girl who was a full year older than me and to whom I’d never actually spoken would not only have visited upon me the most exquisitely painful embarrassment of which a sixteen year old lad could conceive, it would also have invited a lecture that forced me to face up to the hopelessness of my cause.

Then again, what was to stop me from plucking a name out of the air?

“Joanne Robson,” I lied.

“Where’s she live?”

“Uh…Wellfield Gardens.”

“How did you meet her?”

“It was when I was still mates with Pan…I mean Paul Porter.”

I had no idea why, but that seemed to do the trick. My aunt nodded, reached for her handbag and took out her purse.

“I want you to keep this to yourself, Peter,” she said, pressing into my palm not a coin but a crisp five-pound note. “It’s to cheer you up if things don’t go so well with this lass.”

I didn’t feel uncomfortable taking it. After all, Joanne was only Lisa in disguise.

But why should aunt Rachel assume that I’d fail to get off with her?

I wasted little time mulling that question over. A simple errand had left me four pounds and ninety pence better off than I thought I’d be when I finished it. I returned to Ashleigh Close with a spring in my step and a hole swiftly being burned in my back pocket.

It would be a while before I was in such high spirits again.

If you liked this post, you can leave a comment and/or a kudos!

Click the Thumbs Up! button below to leave the author a kudos:

And please, remember to comment, too! Thanks.

Comments

Nice start.

It seems that at least his aunt suspects that he is going to change and that he won't even look at the possibility. Though you can't blame a boy that age for that, can you?

Maggie

Thanks Maggie

Peter's a complex character. I haven't figured him out yet. He's not bothered by the change he's about to go through so much as the fact that people haven't been open with him. Then again he doesn't really understand what he's in for. And he's in love. I should stick to spy stories, shouldn't I?

Well done!

Nice start.

I look forward to reading more.

Hugs

Sue

Similar Story to Tell

Similar Grammar School photo and a Maths teacher called Mr Holroyd who was tough but had great respect.

You'll be treating yourself to fish and chips out of the bag next chapter if I'm not mistaken.

Pity the poor teachers nowadays.

Pendant apes

Well I never realised...

"we'll tell you when you're older"

something tells me the facts of life are going to show up before anybody gets around to explaining some things to him ...

Will be very interesting

to see what happens to him/her.

May Your Light Forever Shine

This is a beautifully written

atmosphere catcher, how have I missed it before. It brings back several sorts of memories of days gone by, though mine would have been just before decimated coinage - that happened when I was in college.

Angharad