Goodbye Master Stokes - Chapter 1: Tempus Fugit

Author:

Caution:

Audience Rating:

Publication:

TG Themes:

Permission:

|

GOODBYE MASTER STOKES

CHAPTER 1: TEMPUS FUGIT By Touch the Light You’re being stupid, I told myself. Plug had made all that up. If Testranol had those kinds of side-effects and they’d been exposed on national television, how was it that nothing had appeared in the papers? Why hadn’t the people who’d manufactured the drug been publicly disgraced? |

Okay, it's another period piece. Anything to avoid mobile phones and the bloody Internet!

To get into the feel of it just hum Rod Stewart's 'Maggie May' or Jethro Tull's 'Life's A Long Song', or if you're really -and I mean really - cool, Family's 'In My Own Time'.

You may think I'm wasting my time

Say what you think, you know I don't mind

I SUPPOSE I'D BETTER ADD A DISCLAIMER

The medical condition described in this story is the product of my imagination. There was indeed a drug that some expectant mothers took in the 1950s and 1960s which in a few extreme cases resulted in girl babies being mistakenly identified as boys, but to the best of my knowledge the condition didn't persist until adolescence. Any resemblance between the product named here as 'Testranol' and an existing drug is entirely coincidental.

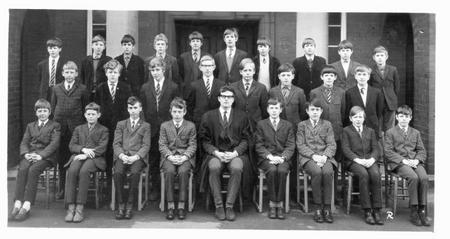

One more thing: this chapter is dedicated to the memory of the late John Oscar Coxon, who taught me History at Hartlepool Grammar School in the early 1970s. His enthusiasm for the subject and his ability to put it across were inspirational, and I am proud to have been a colleague of his during the final years of his career.

CHAPTER 1: TEMPUS FUGIT

October 21st 1971

When Pansy Porter fainted ten minutes before the end of Chipper Wood’s Maths lesson, and we all saw the vivid red smear he left behind as he slid from his chair, there was uproar.

Chipper had difficulty keeping order at the best of times; now he lost control completely.

“Pansy’s having a period! Pansy’s having a period!” we chanted. Desk lids were banged. Pens, pencils, rulers, set squares and protractors went flying across the classroom. Gungies splattered on the blackboard and the wall behind it.

Then Oscar Collings walked in, and within seconds you could have heard a microbe burp.

Bull-chinned and bearded, he swept his uncompromising gaze across every face like a searchlight. It paused as it illuminated Pansy’s slumped shoulders and lolling head, but not for long.

“Chisholm, go to the secretary’s office and tell them to call the nurse,” he instructed the boy nearest the door, each syllable he enunciated demanding your absolute and unwavering attention. “The rest of you…RAFFERTY!”

Oscar took a single step towards the thin, weasel-faced figure at the back of the room. One more and there might have been another, browner smudge for the caretaker to wipe up.

“W…w…what, sir?”

“You must have a very limited understanding of the laws that govern the propagation of light, Rafferty, if you thought I would be unable to see you sniggering.”

“No sir…I…I mean yes sir.”

“You will collect your things, leave the room in single file and gather in the south cloister,” Oscar told the class. “And you will do this in silence.”

He didn’t say what would happen if we disobeyed him. He didn’t have to.

‘Cloister’ was a rather grandiloquent term for the open-sided brick passageway that led from the west wing to the assembly hall, but then Newburn Grammar School had always fancied itself a cut above other establishments of its kind. Many of the masters had graduated from Cambridge; some had dined there at high table. Former pupils had gone on to represent their country at rugby and cricket, to forge successful careers as doctors, solicitors and high-ranking civil servants. One had recently been appointed Sub Dean and Canon Precentor at Durham Cathedral.

I had no such hopes for myself. I was bright enough — too clever for my own good, mum often complained — but I didn’t live behind the park, I wasn’t much use in a scrum, I couldn’t hit a six and I lacked the confidence to break free of the herd mentality that infected all but the affluent elite and discouraged academic excellence in favour of getting along by keeping your head down.

“Here he is!” someone hissed, and the murmuring we’d allowed ourselves to indulge in while Oscar was out of earshot ceased.

“Look over to your left,” he boomed, gesturing with a gowned arm across the car park to the cricket lawn and the belt of woodland that enfolded it. “You will notice that much of the ground is thickly carpeted with leaves. That is because the trees, being of the deciduous variety, are letting them fall. Your O level year is upon you, gentlemen, and it is passing. To imprint this simple concept into the grey matter beneath your skulls, you will all write the following line from Virgil two hundred times: Sed fugit interea, fugit inreparabile tempus.”

“Yer doin’ mine for us, Rafferty,” growled Briggsy.

“Yer can do mine an’ all,” muttered Kendo, not to be outshone.

Rafferty paled but didn’t argue. He was desperate to hang around with the hardest lads in the Fifth Year, even if it meant being treated as a virtual slave. Maybe he imagined that some of their toughness would eventually rub off on him.

Oscar directed us to hand in our work tomorrow morning at break. At this point most teachers would have taken a register so that no one could claim he was absent when the punishment was meted out. Not him; he’d counted twenty-six of us and that was how many sets of lines he would receive.

The dinner bell went and we were dismissed.

“Stokesy…Stokesy!” I turned to find Rafferty offering me a dog-eared scrap of paper torn from an exercise book — no doubt it was intended as the raw material for more gungies — and a chewed pencil. “Write it down for us, will yer?”

“Piss off! I’ve already got to do it two hundred times. Might only have been one hundred if you’d managed to control yourself.”

“Aw, come on Pete! If I get it wrong they’ll knack us.”

“Don’t you remember it from First Year?”

“I wasn’t ‘ere then, was I?”

So the phrase hadn’t been drummed into his brain by a Classics master who believed that learning random quotations from a dead language by heart was an essential part of an eleven year old boy’s preparation for adult life.

“All right,” I sighed. “But you can do the writing. I know where that pencil’s been.”

I recited the phrase for him, becoming increasingly impatient as he struggled with the word inreparabile. Our year were on first sitting this week, and if I was late I could expect a spoon in the forehead from the prefect in charge of the table.

“What’s it in English?” Rafferty asked me once he’d covered the paper with his scrawl.

“But meanwhile it’s flying, time is irretrievably flying.”

He traced the words with his finger, shaking his head.

“Fuck it,” he laughed, then took off after Briggsy and Kendo.

Picking up my haversack, I hurried out of the cloister and along the west wing’s bottom corridor towards the top yard and the well-trodden path through the woods that led to the new dining hall, erected in the spring as the first part of a development that would eventually include a swimming baths and a sports centre. On the way I caught up with Plug and Gash, who were both in a higher Maths set than me and would take their O levels in that subject before Christmas, giving them one less exam to worry about next summer.

“Have you heard about Pansy?” I asked them.

“Yeah, Teeth told us,” said Plug, whose nickname arose not because he was ugly — though we all agreed that he was — but on account of Mr & Mrs Graydon’s failure to realise how their son Philip’s initials would appear if they gave him middle names as pretentious as Leo and Unwin.

“Wish I’d been there,” chuckled Gash.

“Then you’d have got two hundred lines from Oscar,” I pointed out.

“Be funny if it really was a period,” laughed Plug.

“Yer fuckin’ daft or what?” said Gash. “How could it be a period?”

“He might be one of them, er…”

“He’s one of them all right!” I tossed in, feeling a twinge of guilt because I’d once been best mates with Pansy — though that was when everyone still called him Paul.

“Naw, what I was goin’ to say was he might be one of them I dunno what yer call ‘em but there was this documentary on not so long back where there were these kids who had what looked like cocks but they weren’t.”

“What the fuck were they then?” asked Gash.

“Some girly bit that grew bigger than it should’ve done.”

“Yer takin’ the piss, aren’ yer?”

“I’m not!” insisted Plug. “It was this stuff the mothers took to keep ‘em from losin’ the baby ‘alfway through. It made the kids look like lads on the outside, but on the inside they’ve got all lasses’ bits.”

“What ‘appened to ‘em?”

“They waited till they started needin’ jam rags, then they give ‘em these pills that turned ‘em into proper girls.”

“How’d they work? Make it shrivel up an’ go back in?”

“Must do. Anyway, they all got sent to this special school so they could be taught ‘ow to wear dresses an’ everything.”

“Jesus!” cried Gash. “I’d ‘ave sliced me fuckin’ wrists open!”

“I think I would an’ all,” said Plug.

“Me too,” I concurred.

But I didn’t contribute anything else to this conversation. I was so deep in thought that it washed right over my head.

Because I’d remembered someone saying years ago that between giving birth to Jeanette and me, mum had suffered four miscarriages.

And that I might have been the victim of a fifth were it not for a drug called Testranol.

As Newburn Grammar School was located on the south-western outskirts of the town and we lived on the very northern edge of the built-up area, it usually took me about three-quarters of an hour to walk home. I only caught the bus in the direst weather; not only did it have the main shopping area to negotiate, which meant it hardly saved me any time at all, but four new pence a day added up to three quid over the course of a term, enough and to spare for the Jethro Tull LP I needed to complete my collection.

The most interesting section of the journey was right at the beginning. The school stood on a high terrace overlooking the stream after which the town was named; here, about a mile and a half from the sands where the water spread into hundreds of rivulets as it emptied into Cleveland Bay, the burn flowed through a long, narrow open space set out with tidy rock gardens, secluded bowers reached by winding pathways, and grassy slopes interrupted by scattered stands of trees. This was followed by a succession of dull inner suburban streets and avenues, the monotony of the route broken only by the occasional main road that crossed it heading in a dead straight line for the town centre. Often I would try to make it seem shorter by dividing it into stages and counting each one off as I completed it, or pass the time by humming my favourite tunes and using them to create daydreams in which I was the performer and Lisa Middleton my audience, her eyes shining with joy when she began to realise that every song was especially for her.

Today I had no need of such strategies. Pansy Porter’s fainting fit had given me plenty to occupy my mind.

I’d begun evaluating the evidence during Scripture, and it was suggesting some pretty disturbing possibilities. First of all there was my physique to consider: I was slightly smaller and less robustly built than most of my contemporaries, and despite enjoying a normal, active lifestyle my arm and chest muscles were as poorly developed as they’d been when I was in junior school. I hadn’t started shaving yet; the bum fluff that had appeared on my chin a few months ago was a fading memory. My voice had deepened, but not to the extent that it could be mistaken for a young adult’s. Most worrying of all, only the finest down, so sparse it was practically invisible even when I peered closely at it, had ever sprouted from my legs.

On the other hand, I had a sixteen year old boy’s interests and urges. I watched every home game at Clarence Park. I pestered my dad for a moped. I read adventure stories and Science Fiction. I listened to rock music. I’d grown my light brown hair fashionably long. I joined in when my mates organised kickabouts in West Park, and when they bought bottles of Newcastle Brown Ale from the off-door on Thornhill Road and sat on Cameron Bank to swig from them.

And I was in love with Lisa. That clinched it.

Or it might have done if I’d felt the slightest stirrings of lust for her.

You’re being stupid, I told myself. Plug had made all that up. If Testranol had those kinds of side-effects and they’d been exposed on national television, how was it that nothing had appeared in the papers? Why hadn’t the people who’d manufactured the drug been publicly disgraced?

I was still debating the pros and cons when I passed the cemetery gates on Jessamine Road. My long trek was nearly over; another minute or two and I’d be at the crossroads where you could look past the allotment gardens to the fields belonging to Throston Grange and Middle Warren farms, just yards from the quiet cul-de-sac which was the only home I’d known.

Then I saw Lisa. She was on the other side, walking past Jezzie Jailhouse — otherwise known as Jessamine Road Primary School — so I didn’t get the chance to find out if she’d return my smile again, but that scarcely mattered. My mental images of the flame-red hair she’d had cut short on top but at the sides and back still hung almost to her shoulders, the heart-shaped face with the nose that was just a little too aquiline, the denim jacket, the flared jeans and the platform shoes, all of them would now be refreshed. Tonight they’d help me imagine whole worlds which just the two of us would inhabit; Martians might invade, flood, fire, pestilence and even nuclear war might threaten, but Peter Stokes would be there to keep her safe and warm.

First he had homework to do — and two hundred lines to write.

Ashleigh Close was a hotchpotch of 1930s semi-detached houses and short terraces put up the decade before. Number 21 was in the middle of one of the latter, on the left-hand side as you walked towards the uncultivated ground at the northern end. It had a small hedge-fronted palisade, a low wrought-iron gate, a curved bay window and a doorbell that mimicked the chimes of Big Ben. A humble dwelling, to be sure: there was no central heating, you could only reach the bathroom by squeezing around the table that took up most of the space in the dining room, and the lavatory was an extension the size of a pantry built onto the kitchen. But the back garden made up for these deficiencies, and if I no longer courted my parents’ wrath by climbing the apple tree, or needed to escape that of my big sister by hiding among the fuchsia bushes, it continued to be a place where I could practise keepie-uppie, or hurl a tennis ball against the wall of the shed and see how many times out of a hundred I could catch it. All things considered, I could have grown up in far less pleasant surroundings.

The staircase rose straight from the vestibule, so I’d acquired the habit of rushing up to my room, dumping my haversack on the bed, unfastening my tie and throwing it to the floor, then exchanging my grey flannel trousers for a pair of jeans or cords and my shoes for slippers before I did anything else.

And you could tell it was a boy’s room. In the three and a half years since Jeanette had bequeathed it to me by leaving to get married I’d concealed the teddy-bear wallpaper with posters of football squads, rock bands — Sonia Kristina, lead singer with Curved Air, took pride of place — astronauts, comic-book heroes, steam locomotives and spectacular photographs of volcanic eruptions, ferocious wild animals and star-filled night skies. The shelves creaked under the weight of model aircraft, battleships and tanks. Few of the discs strewn around the record player were in their sleeves, fewer still of the shirts, jackets and jumpers in the wardrobe were accorded the dignity of hanging from a rail.

I didn’t plan to spend much time there this evening. It hadn’t been a bad day for the third week in October, yet as the light began to weaken I sensed a chill in the air that the two-bar electric fire would struggle to stave off. I’d have to finish my lines before I went downstairs, otherwise there’d be an inquest I was in no mood to tolerate; the ten ‘quickies’ Sidlet had given us at the end of French and the essay on the causes of the Russian revolution could be done in the front room while I waited for Top of the Pops to come on.

I lifted one of the dozen or so spare exercise books from the pile in the corner — it was easy enough to con the more absent-minded of the masters into giving you a new one, in the Third Year I’d done it twice in one lesson with Pop Sherman — and ripped two double pages from the middle.

Sed fugit interea, fugit inreparabile tempus.

But meanwhile it’s flying, time is irretrievably flying.

As I began to write, setting down all the Seds first to get them out of the way, I had no idea how turbulent that flight was soon to become.

Tea on Thursdays was mum’s chance to experiment, since dad always went to the Labour Club after he left the office and got fed there during the meeting. Sadly the results of her explorations into the realm of foreign cuisine rarely met with success, and tonight was no exception. Although there may indeed have existed parts of the world where cod fillets were coated in breadcrumbs, fried and served with tinned sweetcorn and plain boiled rice, I felt certain that the natives would have come up with something rather more appealing to accompany these delicacies than parsley sauce.

That was as unconventional as it got. The meal didn’t begin until mum had turned off the radio and said grace in dad’s absence; she’d been raised to believe that table manners should be enforced with a severity that would have caught Mrs Beeton out, and showed no signs of mellowing as the years went by. Woe betide Peter Stokes if he should talk while his mouth was full, leave food on the end of his fork, or fail to ask permission before he rose from his chair.

“I want you to run round to your gran’s,” she said in her warm Berkshire accent as we started clearing up. “There’s a pile of magazines on the telephone table, and some books I brought back from the shop.”

“Shall I go now?”

“After we’ve done the washing up.”

It had been worth a try.

The burden I lugged through the front door twenty minutes later was a hefty one, but I didn’t have to take it very far, just to the street that began at the corner of the school. In fact ‘gran’s’ was a misnomer, as she’d died fifteen months ago; the house now belonged to her youngest daughter, my aunt Rachel.

Rachel had a past, which made her unique in the Stokes family. Not that I knew anything about it. How could I, when my polite enquiries as to the identity of the fetching young beauty whose sepia-tinted portrait she kept on the mantelpiece beside uncle Bob’s were consistently answered by my parents with a curt “we’ll tell you when you’re older”?

It was the same with the facts of life. I’d worked out for myself that babies grew inside their mothers’ tummies, but if it hadn’t been for the copy of the Kama Sutra Gash pulled out on the school field one dinnertime I’d never have guessed in a million years what put them there.

All the front doors on Everard Street opened directly onto the pavement. The houses had only one main downstairs room, and back yards instead of gardens. Until I was six or seven a huge tin bath had hung from a nail hammered into the side of the toilet shed; dad had told me that on Sunday evenings gran would boil pan after pan of water to fill it, he and his brothers taking their turn to bathe first and then being sent to bed so they couldn’t watch their sisters undressing. My grandparents must have been remarkable people to bring up eight children in a building this size.

I went in without knocking, and found my aunt in the armchair watching the regional news. She remained a handsome woman, even if by her own admission she was ‘getting on a bit’. I sometimes felt sad that she’d spent so long looking after gran instead of marrying again. Now it looked as if she was destined to drift into old age alone.

“Hiya,” I said. “Where d’you want these?”

“Leave ‘em on the table, love. If you want to help yourself to a drink or a biscuit…”

“No thanks. Just had my tea.”

I took off my anorak and sat in the chair opposite hers. It was the first act in a ritual I hoped would end with her twisting open her purse and giving me a shiny 10p piece.

“How’s school goin’?” she asked, fiddling with the long necklaces she always wore.

“Not so bad. We break up for half-term tomorrow.”

“Is it tatie-pickin’ week already? Doesn’t time fly! It only seems like yesterday when you were in short trousers.” Her eyes narrowed. “Is everything else all right?”

“What d’you mean?”

“You haven’t had any aches or pains lately?”

“Only the bruise I got the other morning when I banged my elbow on a lamp post trying to avoid stepping in a lump of dog dirt.”

“No tenderness anywhere?”

“I don’t think so…”

“You don’t feel tense or angry or bad-tempered?”

This wasn’t in the litany. By now she ought to have been entertaining me with amusing anecdotes about my early childhood, such as the time mum left me in the pushchair outside Timothy Whites and came back to find it surrounded by people listening to me belt out ‘Tulips From Amsterdam’, or when she was berated by the headmistress during my first week in infant school for teaching me to read when in fact I’d taken care of that inconsequential little task myself.

“I’m fine, honestly!”

“Are you sure? If you’re unhappy about anything you can tell me, you know. It won’t get back to your mother and father.”

I wanted to tell her I’d come here to deliver a bundle of magazines and books, not be grilled about my private life. But I needed that 10p, and the only way to coax it into my jeans pocket was to play along.

“Okay, there is someone on my mind,” I confessed.

My aunt leaned forward.

“Who is it?”

“I’d rather not say.”

She rested her forearms on her thighs. Her expression was a blend of deep curiosity and genuine concern.

“Is it a boy?”

“What?”

“This person you keep thinking about. Is it a boy?”

“No!” I laughed. “No, it isn’t!”

“Are you tellin’ me the truth?”

“Of course I am!”

“There’s nothing wrong with havin’ feelings, Peter. You can’t help who you fall in love with.”

I saw her eyes dart to the portrait on the mantelpiece, and suddenly it made sense.

But I was too shocked to say anything. I knew what a poof was; it had never occurred to me that women might fancy each other. And here was my dad’s sister looking at a picture of a young woman who’d once been her girlfriend…

“I…I’m not, you know…” I forced through my lips eventually.

“So what’s she called?”

My heart sank as I realised that I’d painted myself into a corner. Lisa lived half a dozen doors up from my aunt, who I gathered was on friendly terms with her parents. To make a clean breast of my emotional attachment to a girl who was a full year older than me and to whom I’d never actually spoken would not only have visited upon me the most exquisitely painful embarrassment of which a sixteen year old lad could conceive, it would also have invited a lecture that forced me to face up to the hopelessness of my cause.

Then again, what was to stop me from plucking a name out of the air?

“Joanne Robson,” I lied.

“Where’s she live?”

“Uh…Wellfield Gardens.”

“How did you meet her?”

“It was when I was still mates with Pan…I mean Paul Porter.”

I had no idea why, but that seemed to do the trick. My aunt nodded, reached for her handbag and took out her purse.

“I want you to keep this to yourself, Peter,” she said, pressing into my palm not a coin but a crisp five-pound note. “It’s to cheer you up if things don’t go so well with this lass.”

I didn’t feel uncomfortable taking it. After all, Joanne was only Lisa in disguise.

But why should aunt Rachel assume that I’d fail to get off with her?

I wasted little time mulling that question over. A simple errand had left me four pounds and ninety pence better off than I thought I’d be when I finished it. I returned to Ashleigh Close with a spring in my step and a hole swiftly being burned in my back pocket.

It would be a while before I was in such high spirits again.

Goodbye Master Stokes - Chapter 2: Childhood's End

Author:

Caution:

Audience Rating:

Publication:

Character Age:

TG Themes:

Permission:

|

GOODBYE MASTER STOKES

CHAPTER 2: CHILDHOOD'S END By Touch the Light I nearly didn’t ring the bell. I couldn’t escape the feeling that by entering this house I risked bringing to an end the world I’d always known. But I reasoned that really bad news normally took you unawares; if you expected the worst, it probably wouldn’t happen. I lifted my finger and pushed... |

I've just remembered that there really is a place in north-east England called Newburn, a few miles from Newcastle upon Tyne. It has no connection with the fictional town described in this story.

CHAPTER 2: CHILDHOOD’S END

Morning assemblies at Newburn Grammar School were acts of worship. Weddings, christenings and funerals apart, they formed the sum total of my contact with the Almighty. In common with the overwhelming majority of my fellow pupils, I came from a family who considered themselves staunch Anglicans but didn’t hold their creed in such high regard as to actually attend services at the parish church. They therefore got the best of both worlds, paradise in the next one for doing bugger all in this.

My personal philosophy could be boiled down to a single sentence. I believed in God because it was too much bother not to.

Today, the last of the half-term, the service began with 'O Jesus I Have Promised'. This was followed by the headmaster’s lesson. Skelty Boulton had a simple and infallible system: on the first Monday of every autumn term he would hobble up to the lectern in the centre of the stage, turn to the first chapter of Genesis and read it; next day he would read the second chapter, and continue in this manner until July, by which time he’d be in the middle of Joshua. What happened after Moses gave unto the tribe of Levi not any inheritance we were left to discover for ourselves.

It was after Isaac had given up the ghost, and his sons Esau and Jacob had buried him, that the introduction to the closing hymn presented Plug with the opportunity to start whispering into Gash’s ear. They were too far along the row for me to hear what, if anything, was said in reply.

He who would valiant be, ‘gainst all disaster

“I’m tellin’ yer, it’s true.”

Let him in constancy follow the master

“I’ll bet yer any money.”

There’s no discouragement…

“He can’t come back. They won’t let ‘im.”

…shall make him once relent

“Me mam knows ‘is mam. Has done for ages.”

His first avowed intent…

“Summat else an’ all. He’s not the only one.”

…to be a pilgrim.

Was he talking about Pansy? I wondered as we filed out of the lobby. I knew that Mrs Graydon and Mrs Porter were acquainted — and Pansy hadn’t been in registration.

The obvious thing to do was go up to Plug and ask him. But something held me back. Maybe I couldn’t face finding out that what he’d said yesterday about the television programme was the truth.

Or worse, that he might have heard of a drug called Testranol…

He’s not the only one.

Once again I chided myself for being paranoid. Pansy was off school because his parents had decided that with us breaking up today it wasn’t worth sending him back. Case solved.

At the end of double Physics I made my way to the west wing, climbed the stairs to the top corridor and joined the queue outside the masters’ room at the head of which stood Oscar, perusing each set of lines he was handed with the meticulous attention to detail of a Victorian counting-house clerk before giving its author leave to depart. Briggsy and Kendo, whose efforts had evidently been found wanting, waited a short distance from the door; cowering between them was a thin, weasel-faced figure who looked ready to wet himself.

“Yer fuckin’ dead, Rafferty,” Briggsy snarled at him.

“Aye, yer a goner,” added Kendo.

Oscar’s face could have felled forests.

“If either of you miserable wretches dares to utter one more word,” he roared, “I shall go to great lengths to ensure that he arrives at his next lesson wishing he had never left the warmth and comfort of his mother’s womb.”

He collected the rest of our lines, then went into the masters’ room. I had little doubt as to the implement he would be brandishing when he returned.

Rafferty pointed a trembling finger at me.

“Blame Stokesy!” he snivelled. “It’s ‘is fault. He told us what to write.”

“Hang on,” I said, holding up my hands. “All I did was help him with some of the spelling.”

Briggsy eyed me suspiciously.

“You told ‘im to write it?”

“Write what?”

“Yer fuckin’ know what,” said Kendo.

“No I don’t,” I protested. “Rafferty, have you still got that scrap of paper?”

He dug inside his pockets, pulling out a gobstopper wrapped in a handkerchief so grubby I wouldn’t have been surprised to see a cloud of flies spring from it. Finally he found what he was looking for.

I bent forward to read what he’d scribbled down.

Sed fuck it inter ear fuck it inrepairable tempus

“It’s ‘fugit’, you daft cunt,” I yelled at him. “Did you write that out six hundred times and never once think how unlikely it was that Oscar would give us lines with the word ‘fuck’ in them?”

He didn’t answer. Briggsy and Kendo remained tight-lipped too.

Oscar, who was of course standing right behind me, merely tapped his cane against the palm of his hand.

“I’m disappointed, Stokes. I’d hoped someone of your intelligence might have had the common sense to associate with less disreputable company.”

Which is why I walked back along the corridor with sore buttocks to add to Kendo’s invitation to meet him on the field after dinner so that any differences between us could be ironed out in the time-honoured Newburn manner.

And these were supposed to be the happiest days of your life.

I had no intention of keeping my appointment with Kendo. If it had been Briggsy I’d have taken what was coming to me. He fought fairly, and knew when to stop.

Kendo didn’t. If his opponent went down he wouldn’t think twice about kicking him in the stomach, the chest or even the head. I valued my self-respect as much as anyone, but I wasn’t prepared to go to hospital for it.

When the dinner bell sounded I made straight for the path that descended to the burn. I was now a truant, since pupils who ate school meals were forbidden to leave the premises — and with Maths on the timetable that afternoon I’d stay one. How I was going to explain this sudden deterioration in my health to my form teacher the Monday after next was a problem I’d postpone until I could steal a sheet of mum’s writing paper from the pad she kept in the sideboard drawer.

A more pressing issue was how to pass the four and a half hours before it was safe for me to walk through my front door. I needed to formulate a plan of action quickly; spots of rain were beginning to fall, and the air had that muggy quality that suggested a heavy and prolonged downpour. Although getting drenched and catching a bad cold might have been seen by some as poetic justice, I had other plans for the week’s holiday than coughing and spluttering.

The solution came to me as I was crossing the footbridge. I could keep dry and at the same time put my mind at rest concerning Pansy just by calling at his house. Mrs Porter had never struck me as the type who’d be straight on the phone to mum; after I told her my story there was every chance she’d rustle up the meal my grumbling belly was already starting to miss.

Pansy lived on Grantham Avenue, so I didn’t have to deviate more than a quarter of a mile from my usual route home in order to reach it. The detour took me closer to West Park, and into an area of tree-lined groves and crescents that looked more prosperous than they were. I picked up my pace as the rain grew more persistent, regretting too late my decision not to put on my anorak before I left this morning.

The Porter residence was part of a late nineteenth-century pebbledashed terrace set back from the road by small front lawns bordered with mouldering brickwork and ragged privet hedges. The path leading to the door was cracked and uneven, allowing me to scrape away the leaf mulch from the soles of my shoes; with my big toe poking out of my left sock the last thing I needed was to be asked to remove them.

I nearly didn’t ring the bell. I couldn’t escape the feeling that by entering this house I risked bringing to an end the world I’d always known. But I reasoned that really bad news normally took you unawares; if you expected the worst, it probably wouldn’t happen.

I lifted my finger and pushed.

It was Pansy himself who came to the door. He wasn’t more than a couple of inches taller than me, though he had broader shoulders and a fairly strong chin. His mop of frizzy nutbrown hair was as disobedient as always; if he hadn’t been fully clothed I’d have assumed he’d just climbed out of bed.

“Well well well,” he said, “look who it isn’t.”

“Er, hiya,” was all I could manage in response.

“Let you out a bit early, haven’t they?”

“I’m knocking off. Kendo’s after me.”

“Ooh…” he said, pursing his lips. “What have you done to upset that great lump?”

“It’s to do with the lines we got from Oscar after he came in when you, uh…you know.”

He glanced from side to side, as if he feared that the entire Kennedy clan might be about to descend on the house demanding he surrender the bedraggled fugitive forthwith or suffer the most calamitous of consequences.

“You’d better come in,” he said. “I’ve got something to tell you.”

I was shown into a spacious, high-ceilinged but cosily furnished sitting room warmed by a blazing coal fire. While I settled on the sofa Pansy took the chair nearest the hearth, crossing one chunky thigh over the other and folding his arms in his lap. I offered up a silent prayer that all he wanted to get off his chest was a preference for his own sex.

But if God was listening, He gave no indication of it.

“I’ve begun menstruating,” Pansy announced. “That means I’m having periods.”

I couldn’t speak. I couldn’t move. Slowly I became aware of a tingling sensation in my forehead and cheeks. They started to feel very cold.

“You believe me!” he grinned, and for a second or two I clung to the hope that this was just an elaborate practical joke at my expense. I let go when his smile vanished. “I wasn’t sure if you would. I thought I’d have to work much harder to convince you.”

“It’s what Plug said…” I muttered, the words barely coherent even to me.

“Oh him! I might’ve guessed.” He sighed and ran a hand through his untidy hair. “It doesn’t matter. I’m not going back there.”

“Is…is that because…?”

“I’m female. On the inside, anyway. I’ve got ovaries, fallopian tubes, a vagina, the lot. I managed to hide it until yesterday. Won’t be able to now. The hormones set off the correction process, you see. Before long I’ll have started to turn into a real girl.”

I was astonished that he could be so blasé about it. On any list of life-changing experiences, this had to occupy the top spot.

“Plug mentioned something about pills,” I said.

“I have to undergo a course of treatment to speed things up. If that’s not successful I’ll need surgery. Minor stuff. Local anaesthetic, they said. But it shouldn’t come to that.”

“Surgery?” I gulped. “Anaesthetic?”

“Yes, I do seem to be taking it all very calmly, don’t I? The thing is, I’ve known this would happen for well over a year. Mam and dad wanted to give me plenty of time to get used to the idea.”

“But how did they find out?”

“It was after I failed the medical for Lanehead. The doctor wrote to them suggesting an immediate visit to our GP.”

That didn’t help. I’d been all set to enjoy a week in the Lake District studying glaciated landforms, then my parents had suddenly decided they wanted to go on holiday. As a result I was in Devon when the medicals were held.

“And what did he say?”

“To me? Nothing. But he told mam and dad that instead of a penis I had a grossly enlarged clitoris. The urinary tract had become attached to it, so I passed water like a normal boy. Apparently it all went back to when mam was pregnant with me. Too many androgens, I think they’re called, in her system.”

I didn’t know what a clitoris or androgens were, but now wasn’t the right time to ask him to cure me of my ignorance.

“Weren’t you upset when they broke the news?”

“I was at first, obviously. Then I realised I wasn’t some kind of freak, I just had a condition that would eventually be put right.”

“I meant about becoming a girl.”

“That didn’t bother me in the slightest. Why would it? You must have noticed which side of my toast I like buttered.” He winked at me, then sat forward. “Actually I’m getting quite excited now the waiting’s almost over. I had a look at the settlement last night and–“

“Settlement?”

“With the drug company. The case didn’t go to court because they paid extra to keep mam and dad from selling the story to the papers. They won’t be able to hush it up for ever, though. Too many families have been affected. There’s already been a documentary about it, but the people who made the programme weren’t allowed to name the product for legal reasons.”

This was the moment of truth. If I didn’t say something now I might never find the courage to bring up the subject again.

I had to grasp the nettle. I had to know.

“It was called Testranol, wasn’t it?”

“Plug does seem to be well informed, doesn’t he?” laughed Pansy. “Yes, it was developed to prevent miscarriages. Mam had one about eighteen months before she fell pregnant with me, so she took it to be on the safe side.”

I stared at the fireplace. I felt as if I was looking directly into the flames of Hell.

The urge to leap up and run out of the house was almost overwhelming. If I left now I could pretend that I hadn’t come here, that the words I’d just heard had never been spoken.

But I stayed put. If fate had dealt me these cards, no amount of juvenile self-deception was going to improve my hand.

“I didn’t get it from him,” I said. “My mother had four miscarriages before I was born. She took Testranol too.”

Pansy’s eyes lit up. He was literally on the edge of his seat.

“So that’s why you’ve had a face like fourpence ever since I mentioned my period! You’re worried that you might start having them! I don’t know if I should say this ‘cause it’ll spoil the fun — but no, not every foetus suffered from virilisation. The figure’s around one in six. There’s still hundreds of us, mind.”

I sighed with unabashed relief. I had a five-in-six chance of growing into a healthy adult male, odds I’d have committed high treason for less than a minute ago.

“How will I be able to tell?” I asked.

“Easy. If your tackle’s the same as every other boy’s then you’ve nothing to worry about.”

I wasn’t quite sure which aspects of my genitals he was referring to — their size, their shape or the way they hung — but I decided not to pursue the matter any further. I’d quit while I was ahead, even if it might be months before I knew I was completely in the clear.

“That’s all right then,” I laughed. “No problems in that department.”

“I’ll bear that in mind,” smirked Pansy, and to my lasting shame I reddened.

“You’ll see Benny Hill have a number one hit first,” I said.

I was soaked to the skin well before I reached Ashleigh Close. I hardly noticed; my limited capacity for performing mental calculations had nevertheless informed me that out of every hundred Testranol babies, eighty-three had been born with perfectly normal gonads. What were the chances that two of the unlucky ones would live so close to each other they’d attended the same primary school?

But I didn’t allow myself to become too complacent. The only penis I was familiar with was my own — and I couldn’t very well go round to Plug’s or Gash’s that evening and ask them to whip it out for me so I had something to use as a yardstick.

He’s not the only one.

When I got home I found that the front door was locked. I never took a key with me; mum was always back from the shop by a quarter to four at the latest. I trotted through the covered alleyway that led to the garden gate. That was bolted shut as well. Swearing loudly, I threw down my haversack and called on every erg of energy my biceps could produce to hoist my body high enough to scramble over it, bending my legs at the knee to lessen the impact as I dropped to the concrete patio.

I had no luck with the kitchen door either, but I’d spotted that the spare bedroom’s window was slightly ajar. Since it was a casement and opened outwards, I reckoned I’d be able to force my arm through the gap, flick the stay off its fixing, push the pane aside and climb through.

First I needed to get onto the kitchen roof. With the aid of a dustbin, a protruding door latch and a recklessness that arose from a vision of myself sitting cross-legged in the alley for the next hour and a half, I managed to clamber up there. Not bad for a girl, I thought as I felt my lips curl in a sarcastic smile.

It required a good deal of fiddling, and my wrist smarted where I’d scraped it against the edge of the frame, but I finally had the window fully open. I perched my backside on the sill, swivelled and propelled my feet forward as I jumped down so I wouldn’t land on the plastic bags piled beneath me.

Job done. I was out of the rain; I could now concentrate on making up the excuse I’d give mum when she walked in.

Then I spied the object inside the polythene wrapper I must have dislodged from one of the carriers in spite of my best efforts to avoid them.

A plain white cotton bra.

That was odd. I’d supposed the bags were filled with Christmas presents, bought early so as to beat the rush. But who would think a bra was a suitable gift for anyone?

I bent down to see what else they contained. My rummaging uncovered more lingerie, several pairs of tights, a vanity case, a manicure kit, a purse and a shoulder bag, as well as an assortment of creams, lotions, scented soaps and other toiletries.

Including a box bearing the logo FEMCARE. Below it was printed:

Soft natural materials for comfort and dryness. Strong, knitted loops for extra security. High quality absorbency for full protection.

They were sanitary towels.

Attached to the box with sticky tape was a leaflet, published by Durham Education Committee and entitled YOUR FIRST PERIOD.

Having your first menstrual period can be both exciting and scary. It's a new chapter in your life that will last for decades. Some girls have tell-tale symptoms before the onset of their first period whereas others don't.

I didn’t have to look at the mirror fastened to the far wall to know that my face had gone as white as the paper surrounding it.

Your first menstrual period will most likely arrive between the ages of 9 and 16…

Leg or back aches and a slight headache may also occur…

Breast tenderness may be experienced…

Hormonal changes, which occur when your body is preparing for a period, can cause feelings of sadness, anger and tension…

My God...

You haven’t had any aches or pains lately?

No tenderness anywhere?

You don’t feel tense or angry or bad-tempered?

Aunt Rachel might have been reading from this very sheet.

There was but one conclusion to draw: these items were all intended for me.

I tried to persuade myself that my parents were only erring on the side of caution. Perhaps they’d watched the documentary and panicked. How else could they have known what the potential side effects were?

It was after I failed the medical for Lanehead.

A medical I hadn’t attended because I was on holiday.

A medical I hadn’t seen the point of having because just weeks before Dr Campbell had given a clean bill of health following the bladder infection I’d contracted…

Suddenly I was angry. Murderously angry.

They’d known for more than a year — and they hadn’t said a word.

How could they have kept this from me? Did they believe I was too weak to deal with it? Was their opinion of me really that low?

What did they think my reaction would be when the truth eventually trickled from my crotch? Or had they simply crossed their fingers in the hope that my reproductive system might never reveal its bloody secret?

I stormed out of the room and sat at the top of the stairs, my thoughts focused only on the confrontation I was determined to provoke the instant mum came through the door.

We’ve been meaning to tell you, Peter.

Something along those lines, I figured she’d answer. It was what she said when I found out that gran wasn’t going to get better.

She’d soon learn that it wouldn’t cut very much mustard this afternoon.

But was I in danger of jumping the gun?

Dr Campbell had been the family GP since before Jeanette was born. He must have known that mum was taking Testranol. What if he’d read about it in the Lancet or some other journal and had considered it his duty to warn her there was a one-in-six chance that their son was really their daughter?

If your tackle’s the same as every other boy’s then you’ve nothing to worry about.

There was one place, and only one place, where I’d be able to confirm that I was anatomically male. I got to my feet and went off in search of my anorak.

Newburn’s central library occupied the lower floor of a dingy red-brick building on Durham Road, between the town hall and the police station. The reference section was on the left of the unlit entrance hall, its shelves, cabinets, drawers and microfiche screens monitored by a stout, greying matron wearing a long-sleeved mauve dress and a pair of thick-rimmed spectacles. I could tell at once that the sight of a teenage boy, his hair plastered to his forehead and the bottoms of his trousers dripping water onto the floor, didn’t exactly have her overflowing with unrestrained delight.

“Aren’t you supposed to be at school?” she challenged me.

“Early finish,” I lied. “Half-term and all that.”

She gave me a probing stare, one I was in no frame of mind to be intimidated by. If she hadn’t lowered her eyes first, we might still have been facing one another down when the cleaners arrived.

“So what can I do for you?” she enquired.

“I need to find a book on the human body. It’s for a project we’re doing on the er, on the blood and circulation and things.”

“Well there’s a Gray’s over in the corner by the Britannicas. It’ll probably be a bit advanced for someone your age…”

“I just want to look at the drawings.”

That brought forth an even more mistrustful expression. I wondered what she’d say if I told her the first word I’d be hunting for in the index was ‘penis’.

Fortunately the room was almost empty, so I had no trouble finding a table where I could leaf through the gargantuan tome I’d been directed towards without having to shield it from prying eyes.

It was in a chapter called ‘Splanchnology’ that I located a sketch of the organ in question. The evidence remained circumstantial; although my cock was both shorter and lacking in girth compared to the one on the page, and my bollock pouch nowhere near as large, that might have been because I was a late developer.

But my heart knew otherwise. It had assessed the situation more rationally than my brain, and now it presented its findings.

They were clear and unambiguous. My parents wouldn’t have shelled out for all that stuff unless they were certain I’d need it.

A mist of pure rage clouded my vision.

I wanted to score out every line of that diagram, with my fingernails if I couldn’t lay my hands on a knife.

I wanted to hurl the book through the nearest window, then go on the rampage until the bobbies came to lock me up.

I wanted to shout and scream. I wanted to injure someone. I wanted the world to share my agony.

I did none of those things.

A chapter of my life had ended. A new one had still to be written. This time the person holding the pen would be me.

I returned the copy of Gray’s Anatomy to its shelf. With a polite nod to the library assistant, I walked back into the entrance hall.

Only much later did I realise that I was taking my very first steps as an adult.

Goodbye Master Stokes - Chapter 3: Lifting The Veil

Author:

Audience Rating:

Publication:

Character Age:

TG Themes:

Permission:

|

GOODBYE MASTER STOKES

CHAPTER 3: LIFTING THE VEIL By Touch the Light I came to a decision. This was my body, and I wanted to know everything about it. If my parents wouldn’t tell me, I’d have to find the information myself. |

This is a revised version of the chapter that first appeared on the 'tg storytime' site.

'Pit yacker' is a slightly derogatory term used in parts of northern England to describe people who live on the former Durham coalfield.

'Blue Peter' was and still is the BBC's flagship children's programme.

Manchester United won the game at Newcastle by a goal to nil, scored by George Best. I know because I was there.

CHAPTER 3: LIFTING THE VEIL

I tried to say something to my parents that night. I really did. But the right moment never came. This was an evening in 21 Ashleigh Close, not an episode of The Partridge Family.

I went to bed early, and lay there with the light on staring at the ceiling. I’d never given much thought to the future; now my mind was filled with nothing else.

Your first menstrual period will most likely arrive between the ages of 9 and 16…

Pansy wasn’t sixteen until March. I’d passed that landmark last month.

I’d been living on borrowed time. I could have started having periods any day — and apart from the bleeding I didn’t have the faintest idea what to expect.

How long did they last? Was there much pain? Would it hurt to piss, like it had when I’d contracted that bladder infection the year before last? Was that why some women became grumpy once a month?

Once a month? Jesus…

I came to a decision. This was my body, and I wanted to know everything about it. If my parents wouldn’t tell me, I’d have to find the information myself.

Pansy’s having a period! Pansy’s having a period!

No way on God’s green earth was that ever going to happen to me.

I had to act. I had to take control of the situation, and soon.

But how?

Who should I talk to, and how much would it be wise to tell them?

It was then that I began to realise that keeping quiet about the discoveries I’d made had been the right thing to do. I wanted to say goodbye to my boyhood in my own leisurely way; once the ball started rolling my old life would quickly come to an end, and I’d have enough trouble adjusting to my new one without wishing I’d made the most of what little time I had left as Peter Stokes.

I switched off the light, and spent what I’d later learn was a fruitless hour or so trying to envision the changes my body would eventually undergo. I ran my hands down my chest, wondering how large my breasts might grow. I touched my genitals, imagining the day when they weren’t there to impede my fingers as they moved from the sparse hair at the base of my abdomen to the gap between my thighs. I stroked my upper arms, thinking of how soft and silky my skin was going to feel.

All that I reckoned I could handle. What kept me from sleep was the baggage that went with being female, so much of it stashed away in the plastic bags on the other side of the bedroom wall. It was one thing to picture myself as a girl climbing naked into the bath, quite another to put myself in the place of the same girl painting her face or stepping into a skirt.

Although I eventually drifted off, I rose next morning feeling tired and irritable. The usual Saturday breakfast noises floated up from the kitchen — the clunk of pans being lifted from their shelves, the screech of a kettle coming to the boil, the jaunty theme music introducing Radio 4’s travel show — and I resented every decibel. What right did they have to sound the way they’d always done? Who told the universe it was fine to carry on as if nothing had happened?

I stood at the window for a while, watching the frail autumn sunshine colour the farmland on the far side of the allotments. The fields climbed steadily towards the limestone ridge topped by Harton Mill, from where a narrow stream marked by a long line of trees snaked north-east towards Warren Sands and the sea. Suddenly I had the urge to be out there, exploring that little valley like I’d done when I was a youngster, gathering stones and pebbles to make dams, or tossing twigs into the water to race against one another — a child once again with nothing to worry about but what his mother would say when she saw the mud caked to his plimsolls.

I put on my jeans and a grandad vest, then hunted through the old shirts and trousers strewn at the bottom of the wardrobe for my toughest pair of boots and the thick knitted socks that went with them. I now needed to lay my hands on the khaki bush hat I’d bought at the start of the summer. When I finally dug it out from beneath the jumpers and T-shirts stuffed inside the chest of drawers I made sure I removed the Newburn Town badge from the front; if I wandered any further than Crimdon Dene I’d be straying perilously close to pit yacker country, and it would be leaving the path of wisdom to broadcast where I was from.

Downstairs, I found my father in the dining room eating lukewarm porridge while he read the sports section of the Daily Express. Ray Stokes was tall, slim-built and possessed a full head of dark brown hair. A time-served bricklayer, he had exchanged a world of trowels and plumb lines for a more sedentary but to my mind equally unexciting one of actuarial tables and surrender values when he finally emerged from night school with the qualifications he needed to enter the insurance business. He was a practical, no-nonsense kind of fellow in other ways too: he had little enthusiasm for literature other than Dickens, none whatsoever for fine art or music.

But most of all he was a creature of habit. At weekends in particular you could have set your watch by him. Every Saturday morning at half-past nine he’d change his cardigan for a sports jacket, climb into his maroon Morris Minor and drive the short distance to the ‘fish house’ on Middleton Quay. By the time he returned, mum would be ready to accompany him on the weekly trip to the new Hintons at Portrack on the edge of Stockton-on-Tees. They’d be back just as Grandstand was about to begin, meaning I’d miss a big chunk of Sam Leitch’s football preview because it was my job to bring in all the carriers and cardboard boxes and unpack them. After that I could look forward to the nauseating stench of steamed cod percolating from the kitchen for the next three-quarters of an hour.

Well, today I was having none of it.

I used the bathroom before I sat down to help myself to a piece of toast from the rack in the centre of the table. I wasn’t risking my life if I tried to eat before I’d washed, but I had four limbs in full working order and valued all of them.

“Be a good match at St James’s this aftie, won’t it?” dad said from behind his newspaper, referring to the game at Newcastle where league leaders Manchester United were the visitors.

“Yeah, I suppose it will,” I muttered as I struggled to scrape a thin slice of butter from a rock-hard pat that had only been taken out of the fridge at the last moment.

“Man United are in a false position, don’t you think so?”

This was how he made conversation, ending every statement by turning it into a rhetorical question you felt obliged to agree with or else risk the exchange degenerating into a quarrel neither party had looked for.

“You could say the same about a few other teams. Derby, Sheffield United, Man City…”

I was careful not to mention Leeds. They had long been a bone of contention between us.

“Long way to go yet though, isn’t there?”

“I’m a girl!” I screamed at him. “I’m not interested in football!”

Or I should have done. It was what he deserved to hear.

“I thought I’d go for a walk,” I said instead. “Take advantage of the weather before winter sets in.”

“Will you be here for your dinner?”

“I don’t know. Probably not.”

“Better put yourself some bait up then, hadn’t you?”

He turned the page, having never once met my eyes.

You fucking coward, I thought.

But this wasn’t the time to provoke a family row.

I shrugged my shoulders and dipped a knife into the runny marmalade.

Throston Beck reached the sea through a deep defile fringed with marram grass and thistles. Thanks to yesterday’s downpour the channel was full, and had eroded a meandering course across the sands complete with miniature bluffs, slip-off slopes and all the other features I remembered from Geography lessons.

I stood on the top of a low dune and watched a dog splash through the water in search of a stick. It picked it up with its teeth before trotting back to its owner, a woman who from this distance appeared to be about the same age as mum. I frowned at her headsquare, her quilted jacket and shapeless skirt, determined that whatever became of me I wasn’t going to end up like her.

Who then?

I had no idea. How could I, when every second of my upbringing had conditioned me into believing I’d grow into a man?

Just like my father…

Now it began to add up. Dads wanted their sons to be chips off the old block, to tread in their footsteps, to share the attitudes and values they held dear. Anything else and they considered themselves to be failures.

As for mum, it was her reproductive system that had consistently proved incapable of carrying a second child for the full nine months. It was her womb that had nurtured a baby girl who turned out to be so deformed she was brought up as a boy.

My parents hadn’t told me the truth because they were ashamed.

This insight only lasted a few seconds. I still detested them for not having been open and honest with me. As I headed away from the beach, following the stream through the brick archway that took it under the railway embankment, I dreamed up ways to ensure that they suffered for it. I’d wave the bra in front of their faces and demand to know what it was doing in the spare room. I’d make all manner of snide remarks about men being chauvinist pigs, just to see how they reacted. I’d buy a copy of Jackie and leave it in a conspicuous place.

A mischievous smile curled my lips as I realised that the girl I’d soon become had a good chance of turning out to be a bit of a bitch.

It soon vanished. After I crossed the Coast Road I swiftly came to that part of the valley where it swung abruptly to the left and the land rose on either side, blocking out any indication that you were less than a mile from the edge of an industrial town that was home to seventy-five thousand people. The only sounds came from the beck as it burbled over a series of tiny waterfalls, the wholesome melody of nature’s never-ending hydrological cycle.

But the magic had gone. I was too caught up in the momentous events I knew would befall me to enjoy what I was starting to see as my boyhood’s last hurrah. Even the chocolate biscuit I munched as I found a stony ledge to study the eddies and whirlpools seemed to have lost its flavour.

I pictured myself on the Croft End terrace next Saturday at the Aldershot game, standing next to Plug and Gash.

“We don’t want owt to do with you,” their expressions appeared to say.

“What’s she doin’ ‘ere, a lass on ‘er own?” someone called out from the back of the crowd as the boys I’d once considered to be my friends sidled away from me.

The tears came then, the reluctant kind that smarted and stung. They were no relief at all. The accumulated anxieties that had been building for the last forty-eight hours weren’t about to be dispelled that easily.

“Fuck it!” I sobbed, and pounded my fist into the ground so many times my knuckles were grazed raw. “Fuck it! Fuck it! Fuck it!”

That brought back memories of Rafferty’s weaselly face, closely pursued by the pitiless glare Kendo had given me when he’d realised who was ultimately responsible for him getting the whack from Oscar. He wasn’t the type to forgive and forget either; on Monday week I’d have to confront more than the mere knowledge that my days as a pupil at Newburn Grammar School were numbered.

It was too much to ask of anyone.

“Bollocks,” I said out loud. “I’m finished with that fucking place.”

I dried my eyes and clambered to my feet. I was wasting my time here; I had nine days to construct a future that didn’t involve an insurmountable sense of alienation and a good knacking into the bargain.

And there was only one person who could help me do that.

Just as I’d done the day before, I hesitated before ringing the Porters’ bell. I had no real evidence to back me up; short of dropping my pants and exposing my private parts, there was no way I could prove to Pansy that I was in the same position as him. He’d likely think I was insane — or worse, that I was taking the piss.

His mother put an end to my prevarication. One moment she was standing at the living-room window, the next she was opening the door and beckoning me into the hallway.

Mrs Porter was an attractive woman with a trim figure, though her neatly bobbed hair was more thickly flecked with grey than I remembered.

“Have you talked to them yet?” she asked me, smoothing the front of her pleated tartan skirt.

“Uh…talked to who?”

“Your parents, of course.” She opened her handbag and checked its contents. “You’ll have to, you know. Things won’t move along until you do.”

I was too shocked to do more than mumble a few incoherent syllables. That Mrs Porter was aware of my condition — never mind that what she’d said removed any lingering doubts as to its existence! — meant that Pansy must have repeated what I’d told him yesterday afternoon. The one person to whom I felt I could speak freely, and already he’d betrayed me.

“Don’t blame Paul,” Mrs Porter went on. “He was only doing what he thought was best for you. And it’s not as if I found out anything new.”

This was even more outrageous. She’d known all along! How many other people had collaborated to hide the truth from me?

“Who…?” I managed to breathe.

“Your aunt Rachel. She doesn’t think that your parents are dealing with this in the right way. When she discovered that Paul had been misidentified, she came to us for advice.”

“But how did she…?”

Mrs Porter looked at her watch.

“It’s a long story, and as we’re running a bit late this morning it’s one I haven’t got time to tell you in full. All I’ll say is that Rachel and Paul have a mutual acquaintance. In fact she’s here now. Why don’t you go up and say hello?”

I’m not sure how I was able to lift one foot off the floor, let alone climb the stairs. But climb them I did, and it was when I reached the landing and looked through the open door to my left that I saw something that expelled the last remaining traces of air from my lungs.

Pansy Porter, wearing nothing but his dressing gown, sat before the mirror applying mascara to his lashes. The girl in the white T-shirt and flared jeans taking a keen interest in his progress was none other than Lisa Middleton.

“Well don’t just stand there like a lemon,” she said, without turning to look at me.

“Is that who I think it is?” muttered Pansy.

“Afraid so.”

Voices, one of them male, carried up from the hallway. They faded, then I heard the front door close.

“Thank goodness for that,” said Pansy, still concentrating on his eyes. “We can have some music at long last. Do the honours, would you Peter?”

I walked over to the record player in the corner. If it hadn’t belonged to someone else I would have put my foot straight through the bloody thing.

Afraid so.

That simple phrase had sliced my soul to ribbons. For the very first time I was actually in the same room as the girl of my dreams, and this was how she’d reacted to my arrival. It didn’t matter that there could never be anything between us, all I’d wanted was for her to say something nice to me so I could cherish it through the difficult weeks and months to come.

I pulled a Fairport Convention album from the rack, but only because the sleeve was protruding more than the rest. I didn’t care what we listened to. I didn’t care about anything.

When the introduction to ‘Angel Delight’ began leaking through the speakers I turned to see Pansy putting down his brush.

Lisa examined his handiwork, murmuring words of tentative approval. I watched her take what appeared to be a pencil and use it to embellish his eyes yet further while they chattered about people — mainly girls — whose names were unfamiliar to me. I felt like an intruder who’d wandered in by mistake, one who was desperate to leave but hadn’t the courage to do so.

For a long time I just stared at the two of them, wondering what I could possibly do to break the spell I was under.

“Has it sunk in yet?” Pansy asked me, as if he’d only just remembered I was here.

I couldn’t answer. I tried to shake my head, but that was beyond me as well.

“Obviously not,” grinned Lisa.

She knew what he was talking about. She knew I was female. How much more of my world was going to fall apart?

Pansy fired more questions at me. All met with the same response — or lack of it.

“What’s the verdict?” he said to Lisa.

“Looks like delayed reaction to me.” She toyed with the bright red hair covering her left ear. “Any chance of using your phone?”

“Help yourself.”

“Who are you ringing?” I blurted out as the thought of her calling for an ambulance removed my tongue from its restraints.

“Someone who’s been waiting for this to happen for a while, Peter.”

She marched from the room, leaving me alone with Pansy.

“I’ll be straight with you, the next few days aren’t going to be easy,” he warned me. “You have to get away from the idea that you’ll be turning into a girl and accept that you already are one. It’s just that your body’s been fooled into thinking it was male by the nasty trick Testranol played on it.”

That was easy enough for him to say. He had parents who’d possessed the foresight to prepare him for the rocky road we would both be travelling.

I glanced down at my crotch.

“This thing I’ve got instead of a, you know…what exactly is it again?”

“A clitoris. And what you think of as your scrotum is really the tissue that will become your vaginal…you haven’t a clue what I’m on about, do you?” He rolled his eyes. “Look, I’m not the one to give you a sex-ed lesson. I’ll leave that to the professionals. If everything goes to plan, and there’s every reason to think that it will, we–“

“What d’you mean, ‘goes to plan’?”

“I don’t want to go through this alone, Peter. And I’m bloody sure you won’t be able to — if you’ll pardon my French. It hasn’t hit you yet, the number of changes you’ll have to make to your life. I don’t mean putting on make-up or knowing how to fasten a bra, it’s deeper than that. It’s about attitudes, behaviour, all sorts of stuff. But we’ll have time to talk later on. First let’s get your folks sorted out.”

Before I could reply Lisa popped her head through the door.

“We’re green for go,” she told Pansy. “I’ll take over from here. See you in a bit, Paula.”

She led me downstairs by the hand — Lisa Middleton was holding my hand! — and a few seconds later we were standing together on the pavement outside the front gate.

“Paula?” I mouthed at her.

“Why not? It seems like the logical choice. You’ll have to come up with a new name for yourself, I hope you realise. I’d suggest Petra, but that’s what they call the Blue Peter dog!”

She slipped her arm through mine. I forced my brain to focus on weightier matters than the thrill that surged through it.

“So where are we off?” I asked.

“To Rachel’s. She’s got everything in hand. Has had for months.”

“What like?”

“She’s hired a decent solicitor, for a start.”

“I don’t understand. Why would she say anything to you?”

Lisa’s brows did everything but fly from her face and attach themselves to the nearest lamp post.

“You really know how to sweep a girl from her feet, don’t you?”

“I wasn’t being cheeky. I–“

“I know you weren’t. God, how can I put this? Rachel and I became close because we both share the same tastes in…well, the kind of people we fancy.”

I sensed my mouth opening and closing. After a few geological eras had passed, sounds emanated from it.

“You’re a…”

“Yes, and I’ve a feeling that you are too.” Her fingers tightened their grip. “I’ve noticed the way you look at me every time we pass each other on the street. It’s okay, I don’t mind. In fact I’ll go so far as to say you’ll be quite a catch once you’ve been taught how to take care of your appearance.”

“But what about when I start having periods?” I protested. “Won’t the hormones turn me the other way?”

“I doubt it. I was first struck by the curse more than six years ago and it hasn’t made any difference to me.”

We started walking towards Harton Lane. Ten short minutes from now we’d be at my aunt’s, and the point of no return would have been passed — if it had ever existed to begin with.

“You shouldn’t be too hard on your mam and dad,” Lisa said as we came to the corner. “Don’t ever forget that when you were born they looked on you as the son they’d always hoped for. They’ll have to give him up now. And they can never replace him.”

Did that excuse all the secrecy? I was damned if I knew.

But the veil was being lifted. If the future was a cracked, uneven path, at least I’d be following it with a clear line of sight.

I smiled at Lisa. She smiled back. It compensated for a lot.

I almost dared to hope that things might be looking up.

Goodbye Master Stokes - Chapter 4: An Unwritten Book

Author:

Audience Rating:

Publication:

Character Age:

TG Themes:

TG Elements:

Permission:

|

GOODBYE MASTER STOKES

CHAPTER 4: AN UNWRITTEN BOOK By Touch the Light Overhead those harbingers of winter, the Christmas lights, shone weakly in the gloom. The seasons were in transition, neither one thing nor the other. Just like me. |

The Shakespeare quote comes from King Lear, Act 4 Scene 1.

TV21 was a comic popular during the late 1960s. Many of its stories featured Gerry Anderson creations such as Stingray, Thunderbirds and Fireball XL5.

Kali (pronounced ‘kay-lie’) was originally a powdered sherbert into which you dipped a moistened finger. In north-east England it came to mean any kind of cheap sweets — penny chews, liquorice sticks and so on. Another local word for them is ‘ket’.

A fish fritter is a delicacy peculiar to Hartlepool and certain parts of Teesside. It consists of a layer of chopped fried fish between two large slices of fried potato, all covered in crispy golden batter. The trick is not to slice the potato too thickly, a technique honed to perfection by Verrall’s on Hartlepool headland.

CHAPTER 4: AN UNWRITTEN BOOK

The worst is not, so long as we can say ‘this is the worst’.

For once Shakespeare didn’t put it quite as eloquently as he might have. But that statement is as perceptive as anything he wrote.

You never recognise the low-water mark of your fortunes until you’ve passed it.

I’m not sure what I expected that Saturday afternoon when aunt Rachel and I began the short walk from Everard Street to Ashleigh Close. Sitting on the stairs with my head in my hands, listening to dad shouting and mum crying, hadn’t been high on the list.

And that was only a prelude to the flood of counter-accusations that followed, most of them from my father.

“You never had kids of your own, did you? And we all know why, don’t we?”

“You couldn’t keep your mouth shut, could you?”

“There you go again, assuming you know what’s best for him. It was the same with our Jeanette, wasn’t it Sheila?”

My aunt stood her ground. She waited for the storm to blow itself out, then told them about the agreement the Porters had reached with the drug company. She explained the advantages of settling now, before the scandal went public and thousands of other families came forward to claim damages. She gave them the number of the solicitor she’d engaged and urged dad to call him first thing on Monday morning.

I suspect that her parting words were intended for me as much as my parents.

“That lad’s got a lot more character than you give ‘im credit for. He’ll come through this with flyin’ colours, you just watch. And I’ll tell you somethin’ else for free, when he does become your daughter she’ll be one you can be proud of.”

But that wasn’t the turning point.

When aunt Rachel had gone I ran up to my room, preferring the scant comfort of the electric fire to the frosty stillness her departure had draped over the rest of the house. After an hour of leafing through old copies of TV21 I wandered over to the window. Dad was raking up leaves from the lawn, a job he’d normally have dumped on my doorstep while he attended to the more important business of turning over the flower beds. Mum was in the kitchen by the sound of it, probably performing some completely unnecessary chore in an effort to take her mind off the altercation that had upset her so badly.

Now was as good a time as any to try and break the ice.

I found mum pouring currants and sultanas into a huge bowl of cake mixture.

“I don’t really know what to say,” I began, which was true enough.

“Best to keep it buttoned then,” she chuntered, handing me a long wooden spoon. “Since you’re here you might as well make yourself useful.”

This was unbelievable. It was as if she’d just found out I was spending my dinner money on kali.

As I stirred the fruit into the buttery goo I watched her crouch to open the compartment at the bottom of the oven and lift out three baking trays. She placed them on the work surface next to the sink, then took a packet of lard from the fridge and tore off a strip of the wrapping paper so she could grease them without getting her fingers covered in fat.

“Are these for the shop?” I asked.

“It wasn’t just you,” she said. “We have to decide what to tell Jeanette. Then there’s your nana and grandpa.”

I had to stop myself from laughing out loud.

“Who cares what they think?” I complained. “I’m the one whose life is about to be turned upside down. Anyway, that can’t have been the only reason.”

“Your father…”

“I should’ve known. It had to be about him, didn’t it? He’s always got to be in control. I can’t even put the clock right without you telling me to let my dad see to it. So what did our lord and master decree this time?”

“He wanted to wait.”

“What for? Until I staggered into the front bedroom one morning with my pyjamas around my ankles and blood running down my legs?”

“Don’t be silly. He thought that first you might change in…well, in other ways.”

“Other ways? What are you talking about?”

“He assumed that because you weren’t built like a normal boy you’d eventually…what I mean is, you might…well, you might start acting like…”

“Oh I get it! Be a lot easier to break the news to me if I was a poof, wouldn’t it?”

“Peter!”

“Sorry, but that’s what it boils down to.”

She continued smearing lard into the trays. Her eyes were filling with tears.

“All we’ve ever wanted is for you to be happy,” she sniffed.

“Then make things easier for me. Call that solicitor. Tell the school I’m not coming back. Talk to Mr & Mrs Porter. Invite them round for tea or something. I’ll do it if you like.”

She nodded her head, but still couldn’t bring herself to look directly at me.

So that wasn’t the turning point either.

Nor did it arrive the following Wednesday, after our gruelling interrogation at the hands of Michael Sandwell in the dingy Adelaide Street chambers belonging to Sandwell, Rokeby & Brougham.

How did you learn of this drug, Mrs Stokes?

What literature was made available to you prior to the consultations?

You say that you’d suffered four previous miscarriages. What opinions did your GP put forward as to their probable cause?

Did you take any other medication during your pregnancy?

At what point did you become aware that Testranol may have had side effects that resulted in the misidentification of Peter’s sex?

What course of action did you decide upon, and why?

Or even at the end of the intrusive, humiliating medical examination I was subjected to a week later as a pre-condition for Sandwell agreeing to take the case on.

Looking back, the most likely candidate was the time I glanced down at the lavatory bowl and saw the reddish-brown spots that had dripped from my crotch. I didn’t panic; Dr Ainsley had made sure I knew what they heralded, and how I was to proceed once they appeared. But I still wanted to be sick after I’d flushed them away.

At least I wouldn’t have to drink any more of that revolting herbal tea.