Author:

Audience Rating:

Publication:

Genre:

Character Age:

TG Elements:

TG Themes:

Other Keywords:

Permission:

‘AUNTIE GRETE! MUM’S ON THE ’PHONE––She says that Tim’s come back from camp with bubonic plague!’

‘Bubonic plague, dear? Are you sure?’

‘Well, p’raps not Bubonic plague, but Mum says it’s something dead catching that I haven’t had. She says can I stay on here until Tim’s bug-free?’ I passed Auntie the ’phone.

‘Hello, Peggy?–What’s all this Gab’s saying?…About bubonic plague?…Oh I see. Scarlet fever…No-no-no–he’s no trouble; I adore having him here, he makes me feel eleven years old again.’

While Auntie Greta’s on the ’phone to Mum, I’d better fill you in on the facts. My name is Gabriel Chambers. I’m 11, have hazel eyes and what Mummy calls “mouse-coloured” hair and I’m in Yr6 at Tuckton Middle School and as it’s the end of the summer holls, I'll be in Year 7 when school starts again. I’ve been staying with my Great Aunt Greta while Mum and Dad were away at a conference and my big brother Tim was at Scout camp. It was almost my last day at Auntie G’s, and I’d been having such a brilliant time, I didn’t really want to go home.

Auntie Grete’s fifty years older than me and she’s really-really cool–not your usual prim and proper great-aunt–No way–she zooms around on a BMW motor-bike wearing leathers and a Bellstar helmet, and last week she got stopped by the police for doing wheelies away from the traffic lights! And, my ton-up-auntie can swear like a French brickie’s mate–IN FROG!–well cool eh?

‘Am I going to stay here, Auntie Grete?’

‘Yes, my pet. If you went home, you couldn’t go back to school because you’d be in quarantine.’

Tuckton Middle School is just round the corner from Auntie Grete’s, so I won’t need to get up so early. Cool! I like her house; it’s dead old-fashioned inside, except for the kitchen, which is really-really up-to-date. The rooms have yellowing wallpaper and dingy brown woodwork with fake wood grain that looks like somebody ran a comb along it while the paint was wet. In the sitting room there’s a big old-fashioned radio set that she calls ‘The Wireless’–which I think is a silly name because once she showed me the inside and there were millions of wires in it! The dial has really-really romantic names on it, like Hilversum, Luxembourg, Rome and Daventry–

On the Thursday before term began, it was 8th September, Mum had just brought all my school things round, and after she had left, Auntie Grete and I went up the loft to find something for Auntie to give as a wedding present. It was like Aladdin’s cave up there, full of all sorts of treasures, and suitcases galore, mostly, I was to discover, containing old-fashioned clothes.

‘I hate throwing anything away,’ Auntie confided, rummaging through the suitcases. ‘You never know when something might come in handy.’ As she searched case after case, I wondered what she was looking for.

‘Eureka!’ she exclaimed suddenly, waving a strange oriental-looking vase in the air. ‘And look, Gab–here’s my old Tuckton school hat.’ It was navy-blue velour, with a mauve and Kermit-green hatband. She plonked it on my head and pinged the elastic under my chin.

‘Ouch! That hurt! I bet the girls are glad they don’t wear school-hats now!’

‘Sorry, my pet. D’you know, with your longish hair you look just like me when I was your age. I’d forgotten I’d got so many ancient garments up here. Gosh! Here’s a gym tunic I wore to school–I should think I must have been about your age when I wore it.’

She held it up against me; it was navy-blue with wide box-pleats and a square yoke. Auntie Grete had been in my form in 1944. Last term, when it was 50 years since D-day, she came and told us what it was like being at school during wartime. It was really interesting.

‘Good gracious. All my old school things seem to be up here. You might as well have my blazer,’ she said, ‘then you can keep your new one for best. We won’t even have to change the name-tape. Look, it says; “G Chambers.” I know you’re a boy, but I doubt anyone will notice the difference.’

‘Err–P-Please may I try your school things on, Auntie G?’ I asked blushing a deep puce colour. ‘I’ve often wondered what it would be like to wear girls’ clothes and I think it would be rather fun. It’s not as if anyone else is going to see me.’

‘Dressing up’s fun isn’t it? I’ve always loved it and so did your dad when he was a boy.’ She took a rather plain grown-up dress from the trunk. ‘This is one of my Mummy’s wartime frocks. Clothes were rationed, you know, so everything was made to use as little material as possible.’ After more rummaging she held up something else. ‘And this is my ghastly party-frock. Isn’t it absolutely vile? I loathed and detested it.’

No wonder! It was dead yucky–all shiny-pink with puffed sleeves, a Peter Pan collar and flounces. ‘I guess no girl today would be seen dead in it!’ I said. ‘I’d have refused to wear it if I was a girl.’

‘When I was your age, Gab, we had to wear what we were told. Mummy was terribly strict. She wouldn’t even let me wear shorts in the summer holidays like some of the other girls used to.’

‘How awful. I must have been horrible to have to wear dresses all the time. Wouldn't she even let you wear jeans?’ I asked.

Auntie laughed; ‘I never had jeans until I was grown up. Nobody in England wore jeans when I was a little girl, not even the boys–they all wore short trousers until they were thirteen or fourteen.’

While we took everything down to my bedroom, Auntie Greta said; ‘I know what we’ll do, Gab; we’ll both dress up–you in my old gymmer, and I’ll put on Mummy’s frock–and we’ll pretend it’s 1944 again. I’ve got a book of Mummy’s that’s full of wartime recipes, so we can have a real 1944-style supper.’

‘Brilliant! We’ll pretend that I am you and you’re my mum–your mum.’ I pulled off my T-shirt and wriggled out of my rather tight jeans.

‘If you like you could even wear the proper undies,” said Auntie. ‘I know I have a pair of knickers like we had to wear at school.’ Without waiting for my reply she disappeared, leaving me to examine the clothes she had put on my bed. Beside the gym tunic, there was a white shirt a tie and a pair of white ankle socks. After a couple of minutes she returned with a plastic bag containing something navy-blue.

‘I knew I had these, Gab. I was going to give them to the local am dram soc for their wardrobe. Slip your Y-fronts off and put them on,’ she instructed, holding them out for me.

I stepped into them and she pulled them up. They were bigger than I expected and rather baggy with tight elastic round the legs. ‘We all had to wear knickers like this,’ she said. ‘Some of my friends’ ones even had a pocket to keep their hankie in. Now put your blouse on and button it up.’

I slipped my arms through the sleeves and tried to fasten the buttons–they were on the wrong side!

‘It’s a girl’s blouse, Gabriel–or should I call you Gabrielle–so it fastens on the girl’s side.’ It felt strange doing it the “wrong way round” but I soon had it buttoned up to the neck. ‘Now your tie, dear.’

That was easy as I wear a tie to school every day. Then she dropped her old gym tunic over my head and showed me how to tie the Kermit-green girdle round my waist.

‘Sit down on your bed and put your socks on, Gaby,’ she said. ‘Your own black school shoes will do as they are almost the same as we wore in 1944.’

That done she sat me down in front of the dressing table and started brushing my hair. “Shall I have a ponytail like I usually do, Auntie?’ I asked.

‘I can’t remember anyone having ponytails then, poppet. If we had hair as long as yours we had to plait it.’ She gave me a centre parting and then set to giving me two very tidy plaits. ‘How’s that, Gab?–Or p’raps I should call you Greta now? You’re the very image me fifty years ago. If you’re naughty I shall call you Greta Louise like Mummy did when she was cross with me.’

Staring back at me from Auntie’s long mirror was a girl who might have just stepped from one of the old school photos round the walls of the Assembly Hall at school. I rather liked the way the hem of the tunic brushed my knees and the air on my thighs as we walked through to Auntie’s bedroom. I watched as she dressed in her mum’s frock and did her hair in plaits which she pinned up in coils over her ears–like earphones. It made her look exactly like her mum in the photo on the mantelpiece in the sitting room. Then we went downstairs to get the tea.

‘Are you hungry, Greta, darling? Would you like a jam sandwich as well as a piece of chocky cake?’ For a moment I wondered who she was talking to, then I realised it was me. ‘With your home-made strawberry jam? Oooh! Yes ple-ease!’

‘I thought you might. I was always hungry when I was eleven, but rationing meant everything was scarce. We were allowed just one egg a week, and our sweets ration was four ounces, about 120 grams. You go ahead to open the doors, and I’ll bring the tray.’

In the sitting-room Auntie put down the tray and I sat on the tuffet. She passed my sandwich and a wedge of choc cake. ‘Thanks, Auntie Sal. Mmmmm! I love your strawberry jam!’

‘I used to sit there, have my tea and listen to Children’s Hour. We loved the wireless; it brought us the news, which often made us glum, and then cheered us up. Mummy used to let me stay up in my nightie every Thursday to listen to ITMA*. Everyone listened to ITMA, even the King. Tommy Handley was so funny. We adored mimicking the characters, like Mrs. Mopp–“Can I do yer now Sir?”’ she mimicked, ‘or Poppy Poo-Pah–or even Mona Lott, “It’s being so cheerful that keeps me goin’”. Sometimes the siren would go and we’d rush out to the shelter and wait for doodlebugs.’

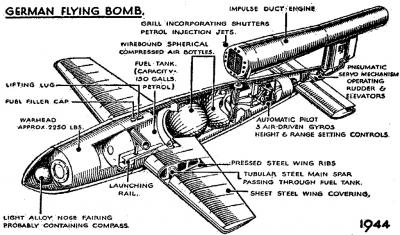

‘Doodlebugs?’ I queried. ‘Weren’t they a sort of rocket thingy?’

‘Doodlebugs were what were called V1s– the flying bombs, like aeroplanes but without a pilot and filled with explosive. Some people called them buzz-bombs because they made a horrid buzzing noise, and had just enough fuel to get here. When it ran out, the engine stopped and the doodlebug crashed to the ground and exploded. The rocket thingies you mentioned were the V2s; they arrived without warning.’

‘I think Hitler was horrible! He made so many people unhappy. Did he make you unhappy, Auntie G?’

‘Yes,’ she replied quietly. ‘My best friend–Wendy–was killed when a doodlebug destroyed her house on the seventh of September 1944–fifty years ago. I cried and cried, and I still can’t remember a thing about that air-raid.’

‘We’re going to learn more about the war next term. Oooh!–It would be fun dress-up in 1940s uniform for school when we do it. I don’t think Wattie could possibly object. What d’you think Auntie G?’

‘What would the other boys say if you went dressed as a girl? And would Miss Watson let you?’

‘Oh, Wattie won’t mind,’ I replied. ‘She’s a real sport, but I hadn’t thought about the boys.’

‘We’ll think about that later then. Let’s put on the wireless, shall we, Greta?’ said Auntie. She clicked on one of the knobs, but nothing happened.

‘P’rhaps it’s not plugged in,’ I suggested.

‘It has to warm up first,’ replied Auntie. It began humming and making whoops and whistles as she twiddled the knob.

‘Hello, children!’ said the wireless, ‘We begin Children’s Hour today with another episode from “The Wind in the Willows” by Kenneth Graham. Part eight, “The Return of Ulysses”.’

‘Brill! Is that a cassette, Auntie? It makes it seem like it really-really is 1944. Amazing!’

‘What do you mean, Greta? Of course it’s 1944! And what, pray, is a “cassette”? It sounds like something rude to me; and why did you call me Auntie?’ (Her voice was different–‘Clever Auntie!’ I thought. She looked younger too!–Dead weird!)‘And it’s high time you started your prep. Go and get your satchel from the hall, there’s a good girl.’

Prep? Did she mean homework?

‘But, Auntie, I haven’t got any homew–err, prep. tonight. It’s still the holls.’

‘The word is holidays, Greta Louise! I will not tolerate your speaking in that slovenly, guttersnipe manner! And why do you keep calling me “Auntie” when I’m your Mummy? I cannot understand what’s come over you. Have you forgotten that you were at school today? Now, don’t be so tiresome and go and do your prep. like a good little girl, or I won’t allow you to listen to ITMA tonight.’

‘Mayn’t I listen to Children’s Hour first? Ple-ease?–’

‘For goodness sake, girl! Go and do your prep this instant, or I’ll be cross. If you’d not dawdled so long at Wendy’s after school, you could have listened to Children’s Hour. You know the rule; “Prep first–Play afterwards.” It’s so unfair of you to play me up while Daddy’s away in the Navy. Take the tray to the kitchen, and then please go and do your prep. There’s a good girl.’

Something really-really weird had happened that I couldn’t understand; so I just said, ‘Yes, Mummy,’ meekly, picked up the tray and took it to the kitchen.

Auntie G’s smart modern kitchen units were gone! In their place was a china sink with a wooden draining board, an old gas cooker, a tall cabinet with a let-down flap, a wooden table and three chairs. I left the tray on the draining-board and went back to the hall.

Sure enough, a brown leather satchel was hanging on the hall stand. I looked inside. It contained a wooden pencil-box with a sliding lid, two textbooks and a green exercise book with; “Greta Chambers. Form 3. English” written on the front. Inside, the neat handwriting was in purple ink. One page was about “parsing”, whatever that was, and there were poems and essays from the summer term. In the last essay, “What I like doing during the holidays”, Greta had made one tiny spelling mistake, and had got nine out of ten. Her teacher had written; “Very good” in red ink. The next page was headed:— “Autumn Term 1944. Preparation.” and on the next line; “7th Sept: Essay: Things I shall look forward to when the war is over.”

In the sitting room Mummy was darning a funny-looking vest with suspenders attached. Looking up, she said: ‘What is the matter with you this afternoon, Greta? You’re acting very strangely. You always do your prep in the dining room. Are you not feeling yourself?’

‘Definitely not!’ I thought, but I replied; ‘I’m alright, Mummy, really. I was just thinking about my essay.’

‘Pop and write it then; there’s a good girl.’

‘Yes, Mummy!’

I crossed the hall to the dining room. How long would I stay in 1944? What if I had to go to school tomorrow? I wouldn’t know anybody in my form! I emptied the satchel, and opened the pencil-box. Inside were two plain wooden pencils, a dip-pen, a fountain-pen, and a wooden ruler marked in inches! I had never used a fountain-pen, only a ball-point or felt-tips. I unscrewed the cap and headed the page; “Things I shall look forward to when the war is over” and underlined it using the ruler. As I took the ruler away, the line smudged––

‘Oh barley-sugar!’ I exclaimed loudly.

The door opened. ‘Greta Louise Chambers! I shall make you wash out your mouth with soap if I hear you using unseemly, guttersnipe language again!’

‘Sorry, Mummy, but I smudged my English exercise book. And I only said barley-sugar.’

‘That’s no excuse, Greta. You know perfectly well it means something much worse. NICE little girls do NOT swear. I cannot understand what’s got into you today.’

‘Yes, Mummeee––’

She stared hard at me–sniffed–and went out.

I enjoy writing essays, and writing one forty years before I’d been born, although seeming a bit weird, didn’t worry me. What luck my handwriting was so like Greta’s! I tried to think what she would write about. Of course! She’d be really-really looking forward to the end of sweets rationing; she’d think that would be dead brill and well wicked! And the latest CDs! And what about the end of clothes rationing? She’d certainly want some really cool gear to impress her boyfriend; and no more doodlebugs or cold nights in the air-raid shelter! After that, the essay did not take long. I had just finished it, when I heard a loud wailing sound.

Mummy burst in. ‘Come along, Greta,’ she said, urgently. ‘At once. Didn’t you hear the siren? Leave your prep till later. Quickly now!’

I stood up and followed her into the garden. In one corner was a grassy mound with a wooden door. The air-raid shelter? We hurried inside. Mummy lit a candle, and closed the door.

We sat, holding hands–waiting and listening. A false alarm? Then I heard it–a droning, crackling, buzzing noise–Getting louder–and louder– and louder––

It was coming closer–and closer––I knew it was directly overhead–I felt really-really scared, and heard myself say: ‘Please, God, don’t let the engine stop now.’

Amen,’ said Mummy, hugging me tightly. I felt a bit braver then. The doodlebug seemed to stay over us for ages. I held my breath, clinging to Mummy, hoping and hoping it was going away.

The silence was unbearable. I clung to Mummy, burying my face in her clothes. After what seemed like hours, but which had only been about ten seconds, there was a ginormous explosion. The ground shook! The candle flickered and went out! I screamed! Mummy hugged me tighter, kissed me and said; ‘That was a close one, my darling.’ I looked up at her and smiled.

After the “all clear” we went back indoors. The wireless was still talking: “Here is the news read by Frederick Allen. British troops in Belgium are firmly established on the Albert Canal, stretching from Antwerp to the German frontier. They’re also firmly installed in Ghent and closing on a big stretch of the Belgian coast, including the ports of Ostend and Zeebrugge. Field Marshall Montgomery has been to Brussels. The Germans in Calais and Boulogne are still fighting it out. French troops from the south––”

The voice faded, and I found myself back in Auntie Sal’s sitting room. My slice of choc cake was untouched, and Auntie Sal was listening to the six o’clock news on Radio 4, and mending the jeans I had torn while climbing one of the apple trees in the back garden two days before.

‘I think must have gone to sleep,’ I said.

‘Did you, Gaby dear? I didn’t notice. I was busy mending. Why d’you think you dropped off?’

‘I must have, ’cause I had the weirdest dream.’

‘Did you pet? What was it about?’

‘Well, I dreamt I was you, sixty years ago, during the war, and I had to do your English homework; it was an essay about “Things I shall look forward to when the war is over.” And there was an air-raid and your mummy and I went to the air-raid shelter in the corner of the back garden and a doodlebug came over and I heard the engine stop. It was deathly quiet, and really-really scary. Then there was a ginormous bang, really close by, and everything shook. After the “all-clear” we went back indoors and began listening to the news. Then I woke up, and you were listening to the news.’

‘Oh, Gabs! That’ll have been the doodlebug that killed poor Wendy,’ said Auntie G, with great sadness in her voice. She stood up, went to the bureau and took out a green exercise book. ‘Do you mean this one, Gab?’ she asked opening the book and handing it to me. ‘I never could remember writing that essay, and Miss De’Ath, our form mistress, was terribly cross with me and gave me a misconduct mark–just because I had smudged my exercise book with my ruler and couldn’t explain what I meant when I wrote: “The end of sweets rationing will be dead brill and well cool!”’

* ITMA: Short for “It’s That Man Again”, a BBC comedy radio programme starring Tommy Handley, that kept everybody’s spirits up during those dark days of wartime and post-war rationing.

see: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ITMA

©2007 Gabi Bunton

If you liked this post, you can leave a comment and/or a kudos!

Click the Thumbs Up! button below to leave the author a kudos:

And please, remember to comment, too! Thanks.

Comments

Well done, Gabi

Lovely story, Gabi.

You have captured the time perfectly.

My Mum was in London during the blitz.

She was down an Anderson shelter when a doodle bug went off in Woolworth about half a mile away.

She never forgot how terrified she was.

You should continue this with further episodes of Gaby going back, if that's possible.

Hugs

Sue

Simply Brill!

You kept the reader guessing as to just where you were going with this, which makes the Twilight Zone/Outer Limits/Torchwood ending all the more delicious.

An insight into WWII

What an engaging view of life during WWII. I find the british way of speaking particularly charming. I hope that you do other tales like this one.

Gwenellen

Thanks…

for your kind words, Gwenellen. Being born just before WW2 was declared, it has had a profound influence on me and my way of thinking. I am glad you find our way of speaking charming, but it is our language after all, (ducking out of the line of fire!!!) however you ex-pilgrims have managed to mangle it over the years.

Massive hugs,

Gabi

Gabi.

Lovely story

Innit? :)

- Erin

= Give everyone the benefit of the doubt because certainty is a fragile thing that can be shattered by one overlooked fact.

Go back and ...

... save Wendy. Then see if there are any changes in 1994.

"All the world really is a stage, darlings, so strut your stuff, have fun, and give the public a good show!" Miss Jezzi Belle at the end of each show

BE a lady!

Period stories

I love this piece. I didn't expect the ending at all. It is reminiscent of some Twilight Zones (and I mean that as a compliment).

barley sugar those blinking doodlebugs!

A really neat story about a fascinating time in history. I was watching A HARD DAYS NIGHT a few years back, and in the background once or twice I'd see a half-collapsed building, and I realized this was damage from either V-1s and V-2's, or the bombs dropped in the Battle of Britian. Over twenty years later they were still rebuilding! And I've heard reports of people finding unexploded bombs & such into the 1980's. Definitely more fun to read stories about than to live thru! Only 2 people died in the continental (non-Hawaii) U.S. from this sort of thing, these weird balloon-bombs Japan sent over on the gulf stream, most of which never got here...

I loved the character of the aunt, all the 1940's touches, the playful way the cross-dressing

element came into it...

~~~Laika

Some people leave a mark on this world while others leave a stain

~Eleanor Roosevelt

.

Laika, Another Unexploded WW2 Bomb…

…was found last year on a building site. It is unlikely to be the last.

Gabi

Gabi.

Would You Believe

My earliest memory is the sound of a doodlebug. My mother had taken me for a walk in the park in Brighton, England (Hove, actually) and there was the loudest buzzing noise I ever heard, really deafening. She pushed me to the ground and lay down on top of me until it was gone. We were lucky in that most of them landed further inland. Rationing! I was 3 1/2 years old when the war ended and we had this huge street party to celebrate. Everyone brought out all the stuff they had been saving for a special occasion. I had never seen jelly before and I was terrified of this wobbly green funny stuff that they tried to make me eat!

Loved the story.

Ah…Hove—

—or British West Hove as a former colleague of mine, who lived there, called it. I know it well, although not in wartime. I spent the war further west along the south coast in Bournemouth, and although I was only 6-years-old by the time VE-Day came around, I have many intense memories almost photographically imprinted of that period of our history. Things like American tanks being parked outside our house before D-Day, being taken by my Mum up on the cliffs and seeing Bournemouth Bay crammed full of ships ready for the D-Day invasion. Nights in the air-raid shelter: we had a Morrison shelter which was effectively a steel cage slightly bigger than a bed inside the house. I slept inside and my Mum slept on top. When the siren went, Mum got in with me, and my grandma put on her tin hat and went out to do her Air-Raid Warden duties. I even had an 'uncle' who was a sergeant in the Home Guard—very Dad's Army!

During the height of the Blitz we had air-raids virtually every night as Bournemouth was directly on the track the German bombers took from the airfields of northern occupied France where they were based to the English Midlands.

And I never saw a banana until after VE-Day.

Thanks for the kind comment,

Hugs,

Gabi

PS I have a line sketch of a Morrison Shelter, but I don't know how to insert it.

Gabi-No-Geek

Gabi.

Morrison Shelter

Here's a page with a good picture of one: Click Here

Oh, by the way... Once you're there, do click the "Back To Air Raid Shelter Page" link for lots of history, more illustrations and additional info on the Morrison Shelter.

Great Ending, Gabi

…so lets have some more.

I think Gaby should have some more episodes with his/her ton-up auntie – PLEASE

Hugs

Norma

Aunt Greta's Woolton Pie

Coming soon to a website near you!

A new adventure for Gabriel and his/her Auntie Grete—Aunt Greta's Woolton Pie—in which our hero/ine learns how we ate in WW2

Hugs

Gabi

Gabi.

COOL?

OK WELL YOU ENGLISH LEVE ME IN THE DARK BUT YOUR STORY IS COOL AFTER I FOUND OUT WHAT A FEW THING WERE WOW HAVE A GOOD ONE AND ILL LOOK FOR PART 2 OR 3 LOVE AND HUGS [email protected]

HAVE A GOOD ONE

mr charlles r purcell

verry good story i wood love to see a lot more of this all i can say is wow verry good thanks for shareing

There'll be bluebirds over .....

I just loved it Gabi.

Charmingly authentic period piece. Nothing wasted, nothing superfluous, with a nicely rounded plot line.

Hugs,

Fleurie

British West Hove (Actually)

Gabi,

Very funny, even though I lived there I never heard that one before. Like you I never saw bananas until after the war and quite frankly it would not have bothered me if I never saw them then. If you can ,keep these lovely period flavour stories coming. You'll make me go all squishy,

Thanks,

Joanne

Fantastic

I think the ending is amazing.

So unexpected.

NS

Great story, Gabi, loved the pix

A great story, Gabi, and I think the pix are brill. I had a satchel just like the one you show and it seemed like it weighed a ton. A useful weapon against bothersome bullying boys.

The ending was tremendous; I never expected it.

Hugs from Hilary

Dead Brill, Gabi.

I just knew that essay would be there! I knew it!!

Dead Brill is right Gabi. The only good thing about

having to wait to get to this story, is that at least

I now have the bunch laid out in front of me!

I've always been drawn to that period in history.

Somehow, it always seemed quite real to me. I think

I shall thoroughly enjoy learning as much about the

life of a little girl during the war, as I will

enjoying the fantasy of being with Auntie Grete!

Lovely, Gabi, and quite Brilliant! Thank you.

Sarah Lynn

Very nice, sweet story!

Loved it a lot. Pretty educational. I have to admit, even though I know a good bit about the battles and the home front here in the U.S.A, I know very little about what happened in Britain.

And about lives for school children in Britain!

Hugs,

Torey

Still Hurts Too Much

O my. Unsuspecting what was in store for me, I started to read this Gaby, and found myself breaking down in floods of tears. I was alive when the doodlebugs were falling on us in WW2. We had already had to move away from London soon after the house was hit by a bomb and I had to be dug out of the wreckage. We were billetted with a family in a small country village north of London, then we found a cottage to rent for ten shillings a week. My Daddy was recalled to the army although he was sick, he had a desk job and could get home most weekends as he simply wrote his own passes and stamped them! But during the week when the air raid warning came we had to huddle into the cupboard under the stairs, Mummy, my baby sister and me. Mummy was terrified and used to grab my arm so hard she dug her fingernails into my skin, when a doodlebug stopped. When the bombers came over, the German planes had a different sound from ours, and she would ask me "Is it one of Theirs or one of Ours?" And I would lie and say it was safe it was one of ours, so that she would not be so scared. When a raid came and Daddy was at home he would take me to the bottom of the garden and let me watch from the top of the wall. The sky would light up with the search lights. Flares would go up and then the AA Guns would fire and sometimes a German plane would be hit and would burst into flame and come roaring down with a Woooorsh sound. Spitfires ( fighter planes ) would dive at the rows of bombers and ratatatat their guns at them, hitting one and then a another. The sky was like a Fireworks display, and with Daddy there I did not feel any fear. He used to say we should all sleep in our beds - if it had your name on it it would get you and if not it would not.

Looking back on all this, I realise what a strange, un-natural childhood we all had back then, what a terrible and stupid thing war is, and how luckier my own children and my grandchildren are, that they did not have to go through such horrible experiences.

Briar

Briar