Author:

Audience Rating:

Publication:

Genre:

Character Age:

TG Elements:

TG Themes:

Other Keywords:

Permission:

Chapter 2 of a Continuing Saga…

Aunt Greta and her nephew/niece Gabriel/Gabrielle

After I told Auntie Greta about what I had thought had been a dream about doing her homework in 1944, she told me that Miss De’Ath, her class teacher, had been cross with her over something I had said in the essay I had written. I felt guilty that I had not thought more carefully about what I was writing.” I realised I must have had a brief sojourn in 1944.

‘I’m sorry I got you into trouble, Auntie Grete, Wattie quite likes it when we use a few modern words in our essays." I took a bite of the chocky cake that I hadn’t eaten earlier. I was still wearing her old 1940’s school uniform–navy-blue box-pleated gym tunic, white blouse, tie and white ankle socks–that must have been my "ticket to the past".

‘That’s all right, Gaby,’ she said. ‘The only thing was I had no idea what it meant so I couldn’t explain. In the end Miss De’Ath decided that it must have been because the doodlebug had interrupted my thoughts and caused me to write gobbledegook. So what did you think of being a girl in 1944?’

‘Not that much different from being a boy in 1994,’ I replied, ‘except for the air-raid–and the clothes, of course. I liked your mummy–she looked just like you do, ’cept a bit younger.’

‘Well, dear, she was quite a bit younger than I am now. She was 31.’

I did a quick sum in my head. ‘Twenty years older than you; Jeez, she’d be 81 now, kewl,’ I stated. ‘That’s really-really old.’

‘It’s not so old nowadays,’ Auntie replied. ‘Let’s get these crocks into the kitchen, and we can load them into the dishwasher.’

‘I didn’t see a dishwasher in your mum’s kitchen,’ I remarked.

‘Good gracious, no. I don’t think they had even been invented. Now I’ll put everything on the tray and we’ll go to the kitchen and decide what to have for our 1944 wartime supper. Will you open the door for me, please, Gaby?’

I opened the door and held it open for Auntie while she carried the tray through to the kitchen. It sounded odd to be called Gaby, but I was wearing girls’ clothes. My name is Gabriel Chambers, but Mummy, Daddy and my big brother, Tim, usually call me Gab–they say I chatter too much and at school I sometimes get called Gab-pots for the same reason.

In the kitchen we put the tea-time crockery in the dishwasher while Auntie emptied the tealeaves from the teapot into her ‘compost bucket’. Now, let’s find that old receipt book,’ she said, reaching up to the shelf where she kept her cookery books and taking down a very tatty old one that had definitely seen better days. ‘I thought we would have a Woolton Pie for our wartime supper tonight, Gabs. We often had it and it was very delicious. It’s named after Lord Woolton who was the Minister of Food during the war.’

‘Wattie told us about him in history last term,’ I said.

‘Well we’ll have his pie this evening. Do you want to help me? I often helped Mummy when she made one,’ she said putting on her apron and tying it behind her back.

‘Yes please, Auntie G, that would be fun.’

‘Then you’d better put a pinny on. Mummy always insisted I wore one when helping in the kitchen so I didn’t splash anything on my tunic. I’ll go and find one for you.’ She left the kitchen, leaving me wishing I knew more about what it was like for children during the war. A minute or two later she returned. ‘There you are, Gaby, I knew I’d seen one amongst those old clothes we found in the attic.’ She handed me a plain white linen apron. ‘This was what we wore at school for dommy sci. Now let’s make our Woolton Pie.’

‘What’s in it?’

‘Well, d’you remember I told you about the rationing and how short everything was?’

I nodded; ‘Yes, Auntie.’

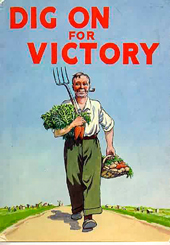

‘Our meat ration was minuscule so we had to make up with extra veggies which nearly everyone grew in their gardens or on allotments.[see note 1] Mummy had an allotment just round the corner and we hardly ever had to buy vegetables. She was one of about four women who had one. The other allotments were all kept by elderly men who were too old for military service. The government had a slogan "dig for victory" to encourage everyone to do their bit.

‘Mummy was a bit naughty, actually,’ Auntie G confided in me, giggling. ‘When she went out to the allotment she used to wear a slightly shorter skirt so that when she bent over the old men could see some of her knickers; she said she did it to encourage them to go out to work their allotments. She insisted it was her bit towards the war effort!’

‘I can’t imagine your mum doing that,’ I said. "She seemed rather serious and strict to me.’

‘Oh, she was very prim, but she was very patriotic and if giving a glimpse her bloomers to a few elderly men would make them go out to dig their allotments, she was up for it. Our knickers in those days were huge in comparison to the ones we ladies wear now.’ She smiled at me and started leafing through the old recipe book

‘I noticed,’ I replied, thinking about the navy knickers I was wearing and how loose and baggy they were in comparison to the briefs the girls at school wore under their netball skirts. ‘So what do we need for our Woolton Pie?’ I asked.

‘Here we are, Woolton Pie. Goodness, this receipt will make one for four people, so we’d better halve the ingredients. It says here that we need a pound each of diced potatoes, carrots, swedes, and cauliflower, I think we’ve got all those–although I remember Mummy didn’t dice the cauli, just separated it into small florets–so we’ll do that. Then we need four spring onions [see note 2] so two will be enough then we will either need some pastry to cover it or we could do what my mum did sometimes and cover it with overlapping potato slices.’

‘I think sliced potatoes would be nice,’ I said.

‘Right then, here’s a potato-peeler; roll up the sleeves of your blouse and I’ll get what we need,’ she said, taking a colander from the pan cupboard and going into the larder. [see Note 3] Auntie had a fridge-freezer, but she also had the larder that had been part of the house ever since it was built back in the 1030s. It was always cool and Auntie kept her vegetables and tinned goods there. While she rummaged for the veggies, I filled a bowl with water.

‘Good girl,’ she said, when she came back. I felt myself blushing, and she must have noticed because she added, ‘Sorry, Gabs, seeing you dressed like that, I forgot you’re a boy.’

‘It’s okay, Auntie, I don’t mind. In fact I’m rather enjoying wearing your tunic an’ stuff. It somehow feels kinda right.’

‘P’raps you should have been a girl, poppet,’ Auntie suggested, tipping potatoes and carrots into my basin of water.

‘P’raps I should. I often play with the girls at school.’

‘You peel and I’ll dice. This swede’s far too big so we’ll only use half of it,’ Auntie stated. ‘While you’re doing that I’ll separate the cauli into florets and slice the spring onions.’ I had soon peeled the spuds and carrots and passed them over to Auntie; then I started on the swede which was much more difficult. When everything was prepared, Auntie put the vegetables in a saucepan, then added a teaspoonful each of Marmite[see note4] and oatmeal together with just enough water to cover everything and put them on the gas to cook.

‘The receipt says they should cook for ten minutes, stirring occasionally so it doesn’t stick to the pan,’ Auntie told me. ‘After that we put it in a pie-dish and let it cool before we sprinkle it with chopped parsley, add the potato crust and pop it in the oven. I’ve saved some of the spuds to use to cover the pie so I just have to slice them thinly.

‘It’s dead easy to make, isn’t it?’ I said.

‘Yes, Poppet, it is. Now if I wash up the utensils we used, would you be a helpful girl and watch the saucepan and stir it occasionally.’

Okay, Auntie G,’ I replied, feeling myself blush at being called a "helpful girl", until I remembered how I was dressed. A few minutes later, Auntie had finished the washing up and came over to look at the mixture bubbling in the pan which was beginning to thicken up and resemble porridge with vegetables in it–not surprising seeing as that is exactly what it was.

‘That looks fine, Gaby; just like I remember it looked when Mummy made it. Turn off the gas now and put the pan on the draining board to let it cool while I light the oven so it gets up to heat. Why don’t you go and read your book?:’

‘Okay, Auntie G.’ I put the hot pan on the draining board and went back to the sitting room. I picked up my book, went to the sofa and sat down. After taking off my shoes, I tucked my feet up under me, smoothed out the skirt of my tunic and got back to the story.

Some time later, I’m not sure how long it was, I heard Auntie Greta going upstairs. Shortly afterwards I heard the loo flush and then Auntie came in and joined me. ‘What are you reading, sweetie?’ she asked.

‘The Picts and the Martyrs,’ I replied.

‘Oh, Arthur Ransome. I loved his books about the Swallows and Amazons; in fact I still do.’

‘This is one of yours,’ I mentioned, ‘I’ve not read this one before and I’m really enjoying it. Nancy is sooo different in this story, not the wild girl terror of the seas, but much more civilised. She’s my fave character of all in the stories.’

‘She’s mine too,’ came the reply. ‘In fact I always wanted to be her when I was your age.’

‘Me too,’ I replied without thinking and then blushed as I realised what I had just said. Here I was, a boy, saying I wanted to be a girl in a story. Auntie must have noticed my blushing because she came over and sat beside me and gave me a hug.

‘It’s all right, poppet, you’re pretending to be me as a girl, aren’t you? Of course you’d want to be Nancy.’

‘It’s not just coz I’m pretending to be you as I girl, Auntie. Even when I’m being me, Gabriel, I want to be her. D’you think that’s wrong? I mean, it’s not right for a boy to want to be a girl.’

‘Is that what you’d like, Gaby?’

‘I don’t really know, but wearing your old school uniform feels right somehow, as if I was meant to wear girls’ clothes.’

‘Have you ever dressed up in girls’ clothes before?’ Auntie asked. I could feel myself blushing again and before I could admit or deny it she added, ‘I guess you have.’

I nodded. ‘Yes,’ I whispered. ‘I found some of Mummy’s clothes from when she was younger that fitted me. I felt so good wearing them.’

‘Does Mummy know?’

‘I don’t think so,’ I replied, feeling tears welling up behind my eyes. ‘I think she’d hate me if she thought I wanted to be a girl. How could I find out?’

‘Well now, let me put my thinking cap on.’ She was silent for a few seconds and then said, ‘Do you know how Tim is?’

‘He’s got scarlet fever.’

‘I know that, but why don’t you phone Mummy and ask how he is; she’s bound to ask what you’ve been doing, so you could tell her about dressing up in my old school uniform for our pretending it’s 1944, and find out what she thinks about it.’ You needn’t tell her about going back and being me as a girl–unless you want to, that is.’

‘Okay, I’ll ring her,’ I said, wiping my tears on the sleeve of my blouse. ‘Sorry, Auntie, I haven’t got a hankie; it’s upstairs in my room and I’ve nowhere to keep it in what I’m wearing.’

‘Most of us girls used to stuff our hankies up our knicker-legs,’ Auntie admitted. ‘Here, borrow mine.’ So saying she pulled her hankie from the sleeve of her dress and handed it to me.

I dried my tears, got up and went upstairs to fetch a hankie of my own. When I came back down I stopped in the hall, picked up the ’phone and dialled–Auntie’s phone still had an old-fashioned dial–the number at home. I could hear it ringing at the other end.

It only rang four times; ‘Tuckton 868517,’ I heard Mummy answer.

‘Hello, Mummy,’ I said. ‘How’s Tim?’

‘Hello, darling; are you all right, you haven’t called me Mummy for ages. Tim’s not very well, but the doctor says that’s to be expected. How are you, sweetie? Are you having fun with Auntie Greta?’

‘Yes, it’s sooo kewl. We’re both dressed up in world war two type clothes. Auntie’s wearing one of her mummy’s wartime utility dresses and I’ve been wearing her old Tuckton school uniform all day. We had a wartime-type tea and we’re going to have a wartime supper from one of Auntie G’s old recipe books; something called Woolton Pie. It’s made from veggies and is in the oven now.’

‘So you’re wearing girls’ clothes, then? You like that, don’t you?’

‘How did you know?’

‘Mums get to know such things. I knew you sometimes dressed up when you were alone in the house.’

‘But how did you find out?’

‘Easy, sweetie, you don’t fold my things the same way I do.’

‘Sorry, Mummy. Are you cross with me?’

‘’Course not, honey. You like wearing girls’ clothes, don’t you?’ she asked again.

‘Yes.’

‘Why?’

‘They make me feel right, like the real me, like I ought to be wearing them.’

‘You mean you feel like you ought to be a girl?’ she asked.

‘Yes, Mummy,' I replied quietly. 'Does that upset you?’

‘Of course not, sweetheart. I’ll love you whatever you are. Look we can’t discuss this on the ’phone; we must talk about it another time when we’re sitting down together.’

‘That’d be cool, Mummy. Give my love to Tim and tell him I hope he gets well soon. Oh, and Auntie G sends her love too.’

‘All right, Gabrielle, my darling. I must go now. Be a good girl for your Auntie. ’Bye.’

‘’Bye, Mummy. Love you.’

‘Love you, too, sweetheart.’ And there was a click as Mummy rang off.

Back in the sitting room Auntie G was continuing to repair my torn jeans. ‘I’ll finish these for you and then you can wear them tomorrow,’ she said.

‘Must I?’

‘Not if you don’t want to; what would you like to wear?’

‘Could I wear some more of your old wartime clothes, please?’

‘If you like, but there’s not a lot of choice. Even then we never had many clothes to choose from because of rationing, but I’ll see what I can find. Unlike you children now, we hardly ever bothered to change out of our school clothes when we got home. I often used to go to play with my school chums–or they’d come round here–after school and we were still wearing our tunics.’

‘But you must have had something else to wear.’

‘Of course, but not much. One of my friends had an elder sister and she got her hand-me-downs. Sometimes a neighbour who had a girl older than me would offer us an out-grown frock; that’s how I got that ghastly party frock. I think I only wore it about twice or three times. But I did get some quite nice dresses, and we had gingham dresses for school in the summer–with baggy gingham knickers to match; my grandma called them "harvest festivals". She giggled, making me giggle too.

‘Why did she call them that?’ I asked

‘Because "all was safely gathered in", as it says in the harvest hymn.’ She put down my jeans and stood up. ‘There, that’s finished those for you in case you want to wear them tomorrow. I’ll just go and see how our Woolton Pie is doing, so why don’t you be a good girl and go upstairs and wash your hands.’

‘Okay, Auntie. I need to go to the loo as well.’

I left the room and climbed the stairs, heading straight for the loo, which was in a small room on its own. I opened the door and got a surprise–it was different: instead of the modern loo pan with a smart white plastic seat there was an old-fashioned-looking one with a wooden seat and the cistern for the flush was high up on the wall with a long chain instead of Auntie’s nice modern low cistern with a handle. I realised that I was once again in 1944. I lifted the seat, raised my skirt and put my hand up my knicker-leg to find my willie. IT WASN’T THERE! I looked inside my knickers and discovered that in place of my penis was what my cousin Kate called a "front-bottom". So not only had I slipped back in time again, but I had changed sex as well. ‘Kewl,’ I thought, then, ‘Help, how do I have a wee?’ I realised I had to sit down, so I dropped my knickers and did just that and relieved myself. I remembered that girls had to wipe themselves afterwards so as not to get drips of wee on their undies, so I pulled off a couple of sheets from the roll. It was horrid paper–not the nice soft Andrex loo-paper that I was used to, this was more like tracing paper that we used in art lessons at school and had "Bronco" printed in the corner of each sheet. I discovered that my front-bottom was rather sensitive and the "Bronco" was rather rough and scratchy. I was in shock and after pulling up my knickers and shaking out my skirt, went to my bedroom to think things out.

My bedroom was different too: in one corner was a large dolls’ house and there was a teddy-bear and two dolls lying on the pillow of my bed. The bookcase was absolutely crammed with books and I recognised the dust jackets of several of my favourite Arthur Ransome books. I thought about getting a book and sitting down to read, but decided I should explore before I was whisked back to 1994. I went to the chest of drawers where my 1994 clothes were kept; would they be there? I opened the top drawer where my t-shirts and Y-fronts should be: knickers in various colours, white, pink, pale blue and navy, and what I took to be vests. I went over to the dolls’ house; and kneeled in front of it; the whole of the front opened to show the inside; it was beautifully set out with miniature furniture.

I was just going to examine it more closely when I heard a call from downstairs; ‘Greta, are you all right? You’ve been up there an awfully long time.’ It sounded like Auntie G, but I realised it must have been Greta’s Mummy.

‘I’m all right, Mummy,’ I replied, remembering that she objected to slang.

‘Will you come down, two of your school chums are here, Susan Brown and Judith Wilson. They want to ask you about tonight’s prep.’

‘Just coming, Mummy,’ I replied, getting to my feet. I quickly shook out my skirt and headed downstairs. In the hall stood two girls about my age, dressed in the identical uniform to mine. One was blonde with pigtails and the other had dark hair cut in a bob with a navy-blue ribbon keeping it from flopping over her eyes

‘Hello, Grete, Judy and I never wrote down what the Grim Reaper told us to do for our prep tonight,’ said the blonde girl who I worked out must be Susan. ‘Can you remember what it was? We were going to give you a tinkle to ask you, but our phone’s not working since that doodlebug dropped.’ I couldn’t help giggling when I heard that Miss De’Ath’s nickname was "The Grim Reaper".

‘It’s an essay called "Things I shall look forward to when the war is over"; I thought of things like the end of sweets rationing–‘

‘–and clothes rationing,’ squealed Judy. ‘What are you looking forward to, Sue?’

‘Being allowed to swim in the sea again,’ admitted Sue. ‘We have super beaches here, but what use are they to us with the anti-landing defences and all the mines? That should be quite easy, then, and the Grim Reaper doesn’t want it till Monday so there’s lots of time. Wo0uld you like to come and play for a bit?’

‘Yes please, but I’ll have to ask Mummy first. It’ll soon be our supper time’

‘All right, we’ll wait here.’

I headed for the kitchen where Mummy was wiping some cutlery. ‘Mummy, Sue has asked if I can go out and play with her and Judy.’

‘It’s nearly supper time and I would like you to lay the table in the dining doom, so I’m afraid you can’t go and play with them tonight.’

‘Oh, Mu-um!’

‘Ask them to come and play here on Saturday. They can come to tea.’

‘Okay, Mummy,’ I replied and got a "look". I don’t think she liked the "okay". I went back to the hall.

‘Sorry, Sue, but Mummy says our supper’s nearly ready and she wants me to lay the table. But she says would you and Judy like to come round here for tea on Saturday?’

The two girls looked at each other and nodded. ‘We’d love to, Grete, but we’ll have to ask our mums. We’ll tell you at school tomorrow.’

‘Okay.’

‘So long, then, and thanks for telling us about our prep,’ replied Sue. ‘G’night, Grete,’ she added, giving me a hug.

‘G’night, Sue, g’night, Judy,’ I replied, and I hugged her too.

‘G’night, Grete,’ replied Judy.

I opened the door for my friends and let them out. ‘’Bye,’ I called as I watched them walk down the path to the gate and wondered if I would be here for them when they came to tea on Saturday or if it would be the real Greta.

To be continued–

” see Aunt Greta’s Homework http://bigclosetr.us/topshelf/fiction/4837/aunt-gretas-homework

1 Allotment garden: see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Allotment_%28gardening%29

2 Spring onions: Scallions to our American (and other) friends

3 Larder: see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Larder

4 Marmite: A vegetable (yeast) extract popular in UK, especially spread on hot-buttered toast. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marmite

If you liked this post, you can leave a comment and/or a kudos!

Click the Thumbs Up! button below to leave the author a kudos:

And please, remember to comment, too! Thanks.

Comments

Terrific, but I'm curious ...

... what sort of vegetable is a "swede?" And can you substitute another veg for cauliflower? Everyone in my house hates the stuff. I thought it might be fun to make Woolton Pie for the family, but swedes leaves me totally confused.

LOVE the story, by the way. I've always been a sucker for time travel tales, and this one has all sorts of terrific tidbits about the time Gabi pops to as Greta.

Looking forward to more! Thanks for giving me another serial to look forward to here. *hugs*

Randalynn

Swede—a member of the turnip family

Hi Randalynn,

A swede is a yellow'orange turnip, what the Scots call a neap and as such when mashed (bashed in Scotland is one of the two accompaniments for Haggis, the other being mashed potato and not forgetting the dram of Scotch poured over the haggis when serving it.

This recipe, I have it on excellent authority, was invented by the head chef of the Savoy hotel in London and designed to make use of vegetables that were readily available in wartime Britain. I suppose tyou could substitute another vegetable if you detest cauli, try parsnips, I have seen a version of the recipe that used them instead of the cauliflower.

Hope this helps,

Hugs,

Gabi

I have just looked up swede and found another name Rutabaga

see: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swede

Gabi

Gabi.

Swedes

In the US, Swedes are more often used for animal feed (esp. for hogs) than they are directly by people. When you find them in supermarkets, they're typically waxed, having been dipped in hot paraffin (note: "paraffin" in Britain is kerosene, not the white/translucent candle-wax by the same name in the US) to seal and preserve them. Depending on how long they've been sitting around, they might be more or less edible -- the wax stops them from drying out, but it might not prevent rotting. They're typically roundish, the size of a softball, very hard, dense and heavy, with flat spots where the root, top and any spoiled bits were cut off. The tough skin needs cutting off before cooking, and the wax comes off with that. They're frequently called yellow turnips, and you'll find them in the standard "mixed vegetable" cans and frozen foods.

They're generally out of favor, but go well in stew recipes for red meats. They have a mild aromatic flavor, but don't use too much as they are more than capable of overwhelming the other flavors.

The other warning perhaps due is that like cabbage, they can be a "gassy" vegetable.

Waxed ...Why?

It's called paraffin wax over here Pippa, although why anyone would want to dip a swede in it, or in any other wax beats me. Are carrots and turnips and beetroot also dipped?

Maybe you store them longer over there, although why you should again baffles me. And if usually used as cattle/pig feed how do the animals get the wax off? :) No wonder it makes them fart.

But they are good to eat. By humans. As Gabi says they are a traditional accompaniment to haggis. As, apart from the dram poured onto the haggis itself, they are, also traditionally, washed down in a continuous fashion with more drams, it is doubtful though that many Scots can remember what they taste like by the end of the meal. Or indeed what they are, or whether any have been eaten. But then that is the secret of the true Scots cuisine.

There is a similar vegetable, but of a much coarser nature, called a mangold-wurzel (or mangel-worzel) that animals are fed on. (Or perhaps were fed on as I have not heard of it of late.) I recall seeing machines for slicing them. I have no personal experience of eating these but wouldn't recommend them, although the name might encourage one to try. Just for the hell of it. As far as I am aware the Scots don't eat them either although I suppose washed down with copious drams of whisky and munched between mouthfuls of haggis they might be palatable. If one could only remember .....

But you must try swede mixed with carrots. If you can find a fresh, unwaxed one, that is.

Hugs,

Fleurie

P.S. Incidentally paraffin wax is very useful in sealing the tops of jams, chutneys, and similar preserves. I have home made apple chutney, and damson & apple jam, cooling in the kitchen as I type, that has been thus treated.

Swedes

Apart from being Scandinavians they are very similar to turnips. Some of our meat in those days was WHALE. I never liked it much, either. Ah, Gabi, I also remember when they dismantled the barbed wire along the coast and I was allowed to take my first walk on the beach. I'm waiting for the next wonderful episode!

Whale, whale, whale…

Yes, Joanne, I also remember whale meat; my main memory of it is that it was terribly tough and tasted a bit like fish-flavoured steak—Yukk.

Incidentally the allotment episode is from real life; my own dear mama—who was very far from prim—used to make a regular exhibition of herself while pulling carrots or digging up spuds to encourage the old men to do their bit!.

Glad you're enjoying it,

Hugs,

Gabi

Gabi.

Continuing Delight.

Gentle and convincing. I really am enjoying this.

Thanks Gabi.

To those who have never eaten swedes, you should remedy the omission without delay. You have been missing out! They are quite delicious, particularly in peacetime. To my mind best when mashed 50/50 with carrots.

Hugs,

Fleurie

The Object of Rationing

Was to make the British as self-sufficient as possible in food since Hitler had his U-boats out there sinking our ships as fast as he could go. That's why we ate all these things that are now considered as animal feed. Apart from swedes we used to eat the outside leaves of cabbage boiled to a pulp (yuk!), brussels sprouts, beets and all sorts of likewise stuff. Meat used to include dishes like tripe (and onions) which I still remember with horror, liver, kidneys, hearts, brains, sweetbreads,etc. Really, I think only the fur got thrown away! That may be why the term English cuisine is considered an oxymoron.

Enjoy,

Joanne

Offal

My Sweetie grew up in Newcastle, in the English North. Organ meats and offal were very much a part of cuisine there, since forever, and I don't think it has anything to do with the War. It has more to do with the North being generally poorer than the South (and necessarily less squeamish?), and all the good cuts of beef going where the money is. In a way, there's a parallel to our own U.S. South and the cuisine known as Soulfood. Less expensive ingredients being rendered edible through necessary creativity and local flourishes to the point where they become addictive and nostalgic to those consuming them.

Lovely Story Gabi!

It brings back memories of years gone by.

I was born several years after the war, but even then times were rough.

I like the Susan Brown character. She's obviously stunningly beautiful and very brainy.

I look forward to the next chapter soon.

Hugs

Sue

I hope you didn’t mind

I was fishing around for a couple of names and I remembered my best friend at school after the war was called Susan Large (she was quite small, really) and then, for some reason, the name "Susan Brown" came to mind; I don't know why!

I just thought you'd like to be brought into the story,

Hugs,

Gabi

Gabi.

Wonderful

As a vegetarian, I'm going to try Wooltom pie myself.

Great story more please soon

Norma

Aunt Greta's Woolton Pie

Gaby,

I have to tell you, your account of life during the War (WW2) was so accurate and real it made me burst into tears. How did you get it all so vividly? I was there, having been born before the war, and I rememeber the Blitz - was in bed in our house in London when it was hit and had to be dug out from the rubble. I was then evacuated, luckily and unusually together with my parents, in fact we were evacuated twice, as the first time we were sent to the Essex Coast, and my Daddy decided that this was daft because if he were a German this would be the ideal place to land if invading Britain, so back we went and collected our emergency supplies and got evacuated again, and billetted with a family further west in the deep countryside as it then was.

Rationing was not all that bad, as there were the allotments, but also nearly everyone had some chickens and or rabbits in hutches in the back yard, and there was also the Black Market.

The Doodlebugs did not come until nearly the end of the war. I remember when my Daddy was away with the Army, whenever the air raid siren went, Mummy took me an my baby sister into the cupboard under the stairs to sleep, and when I heard the planes coming over, the German planes had a different sound from the British ones, and she would clutch my arm and ask "Is it one of ours?" and I would lie to her that it was one of ours so that she would not be so afraid. When Daddy was home he insisted we slept in our beds, and used to take me out to the wall at the bottom of the garden to watch the planes flying over to London, to drop their bombs, and the search lights picking them out, and the barrage balloons, and the Anti-Aircraft gun fire exploding among them, and one or two getting hit and coming down in flames. And the Spitfires rising and charging down on them to shoot them down. It was very exciting, and with my Daddy there I never felt afraid at all. He used to say it was no use trying to hide, if it had your name on it it would get you, and if it did not it wouldn't.

Nevertheless, the All Clear tone was such a heart-lifting sound, such a relief to hear.

Adults were mostly very strict with kids back then - the way children behave today would be unheard of, but actually I prefer the way children can have a discussion with you as equals to how we had to behave with adults back then. I guess I was a bit luckier than most, because I learned to read at three and picked up a more adult vocabulary, they did not mind chatting with me as though I was a small adult.

I remember digging carrots on the allotment, and taking eggs to people to get extra bacon or sugar or tea. My Daddy was originally Jewish, and had rebelled, and we had bacon for breakfast almost as a religious ritual every day! One big positive thing about those days was how everyone helped each other so much, people are mostly far more selfish nowdays. Sad that it took a war to make them nice like that. Anyone who has actually experienced war must surely agree that it is a disgraceful thing that should be banished from our world. I am ashamed that even my generation failed to abolish it.

Briar

Briar

Woolton Pie

Fleurie said it best, Gabi. The story is gentle and convincing.

Not only is the story a convincing and a pleasurable read, it's

also like a history lesson. I really appreciate how you make

the effort to add the little details of everyday life, and then

you take the time to explain them to those of us who would have

no idea.

I think this is a wonderful work, with a literary quality to it.

I also think you must have done an ripping good job on that theme,

because it is your writing that is gentle and convincing. I'm

very impressed.

Sarah Lynn