Author:

Caution:

Audience Rating:

Publication:

Genre:

Character Age:

TG Themes:

Permission:

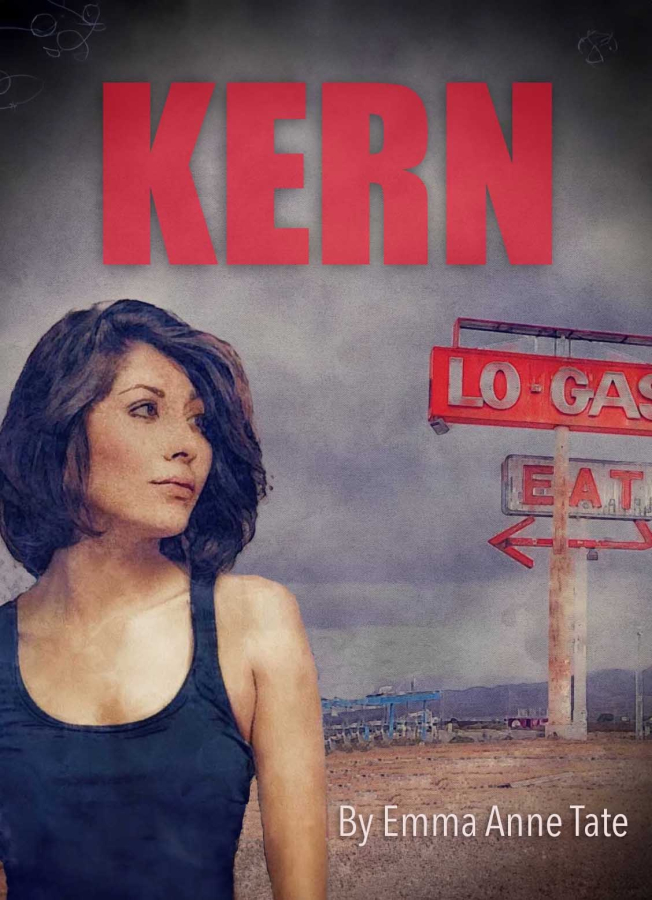

Carmen Morales is a twenty-nine-year-old transwoman who works for an insurance broker in Orange County while attending law school at night. She and her two roommates are celebrating the successful conclusion of her spring semester when she is summoned back to the Kern County home she was kicked out of eleven years before, by the Grandmother – “Abuela” – who refused to intervene. Her father has had a stroke and is in a coma. She spends several days there and reconnects with some members of her extended family – Abuela, her brother Joachim (“Ximo”), her uncle Augustin, her senior aunt Maria, and some of her cousins – Kelsey, Inés, Guadalupe, and Gabriella. None of the interactions are free of strain, but she succeeds in coming to terms with Ximo, Kels and Innie – and even, to a certain degree, with Abuela herself. Abuela convinces a very reluctant Carmen to apply to be temporary conservator for her father.

Returning to Buttonwillow after three days back in Orange County for work, Carmen runs into her old history teacher and learns he had taught her padre as well. Her car breaks down on the way to her motel, and her cousin Jesus helps her. Then she and Kelsey have dinner together.

Chapter 15: The Shadow of the Hawk

Another day.

I was back in padre’s room, regaling him with more stories of the eleven years I’d spent away from Kern County, waiting for Abuela to show up. I had called her the prior evening before going down to the motel pool with Kelsey, but she had apparently been dealing with a migraine, so I’d arranged to meet her at the hospital in the morning.

The thought was jarring, in a way. All the time I was growing up – almost 18 years – I couldn’t remember Abuela being sick. I’m sure she had been, now and then. Who isn’t? But I had no specific memory to back up that intuition. Not one. If she had ever been ill, she’d never let it show. For sure, she’d never let any illness stop her.

“Where was I?” In my wool-gathering, I’d lost the thread of my story.

The comatose man by my side gave me no help, and made no complaint.

“Oh, right. So anyway . . . You can see why I just had to get out of that group house. So I saved up a bit of money. Not much, but enough for a security deposit, maybe first month’s rent. And I saw an ad from a couple of girls, looking for someone to share space in a three-bedroom down in Santa Ana. You have no idea how stressful that was, when I went to see them that first time.”

I could smile at the memory – now. But then? Different story.

“I was shaking – literally shaking – when I walked up the stairs and found the door. I wanted them to see another girl. Nothing else. I wasn’t going to lie to them; I was done with all that. But telling them about being trans – that would come later. First, I wanted them to look at me, and just see . . . me. You know? The person I knew I was.” I gave padre a hard look. “The person you were never able to see.”

I fought down my anger and continued. “I knew I could pass. I’d done it for a year at the shelter, before Fatima caught me. I’m only five-seven, and I’d always had a slight build. I’d gained back a little of the weight I’d lost when I was living on the streets, but I was still super thin. My hair was thick again, and really full, ’cuz I’d learned how to take care of it, and ’cuz of the HRT. My face was feminine enough, especially with a little help from makeup.”

The thought of what padre would say about my HRT and makeup – if only he could speak! – made me smile wickedly and add, “I’d also gotten really good at stuffing my bra in a realistic way, and slipping a little subtle padding on my hips and ass. That helped too.

“All that was good, but you need to understand, for a woman that’s just the start. I spent hours trying to decide what to wear, even though I didn’t exactly have a huge wardrobe. Just enough for work, and a couple things for when I was off. I figured capris were appropriately informal. And they showed off my legs, which are one of my better natural features – just so you know. I agonized between a nice T-shirt and a capped-sleeved cotton top with a pretty pattern. T-shirts are kind of boring, but they say ‘casual’ and maybe ‘fun.’ I didn’t want them to think I was some sort of princess. On the other hand, T-shirts are more androgynous, and I definitely didn’t want that.”

I ran a finger lightly down the thin gold of the chain at my neck. “I didn’t have to think about jewelry. Apart from a set of studs that I’d gotten with my piercing, just before I started work, I didn’t have any. I did have to think about shoes, but for ‘casual’ my choice was only sneakers or a pair of sandals, so, sandals it was.”

The door was there. The number matched the ad. The girl I’d talked to on the phone . . . she’d sounded nice. How bad could it be? Surely it would be okay. PLEASE let it be okay!!!

I probably stood in front of the door for five minutes. Then it opened, and a short Chicano girl with soft eyes and a kind expression gave me a gentle smile. “You must be Carmen. Please come in. We don’t bite.”

A voice from inside the apartment shouted, “Hey, hang on! I bite!”

I took a steadying breath, and produced a smile of my own. “Lourdes?”

I looked down at the man in the bed, and shook my head. “It’s all stuff guys wouldn’t spend a minute thinking about, right? I mean, even a cis girl would worry about what to wear, and what kind of impression it would make. But guys? It’s just jeans and a Tee, and don’t worry too much if you don't have time for a shower.”

“Do you miss it?”

I’d been so engrossed in my memories that I hadn’t focused on the sound of slow steps approaching the door, and I jumped to my feet, startled. “Lupe! Don’t do that to me!”

She smiled slightly and pivoted, bringing Abuela in line with the door, before murmuring, “Straight ahead.”

“Good morning, Abuela,” I said, feeling oddly formal.

“No change?”

I knew she didn’t mean me. “None to see, and I spoke with Dr. Chatterji yesterday. That’s her impression as well.”

She grunted an acknowledgment as Lupe guided her to the chair I had vacated. She lowered herself into the chair, using the arms to guide and control her descent. “You are telling him stories?”

“I got the idea from someone you may remember – señor Cortez, the history teacher. When I showed up yesterday, he was reading to padre. He said some coma patients may be aware of their surroundings, even if they can’t respond.”

“I remember him.” Her voice was dry, but then, that was kind of her default setting.

“He remembered you fondly – the ‘formidable mamá Santiago,’ I think he said.”

“He was a fool.”

I bristled at her casual dismissal of a man I admired. But I bit back my hot rebuttal, counted to three in my head, and gave a response that was both short and cold. “I disagree.”

Her head swiveled to where I was standing. “He believed in education for its own sake. Like being stuffed full of knowledge makes you better or something.” She shook her head. “Even though he was some kind of radical, he still thought like a stupid hidalgo.”

“You were happy for his help getting padre into college,” I retorted.

“Happy? I would have been ‘happy’ if Juan had learned that education is the way to get ahead in this country. The only way. Maybe then he would have valued it more.”

I’d had enough. “Sure. Blame señor Cortez. Blame my mother. Blame me, if it makes you feel better. Why not? But you are only fooling yourself if you do. Padre made his own choices.”

“You think I don’t know that?” She shook her head angrily. After a moment, though, she waved a hand tiredly. “Why don’t you two go somewhere for a while? I need some time with my son.”

I shot Lupe a glance.

She grimaced, then shrugged.

“Okay,” I said, unwilling to argue. “We’ll be back in a half hour or so.”

She didn’t bother to reply.

Lupe didn’t say anything until we reached the elevator. “Welcome to the fun part of my life.” It could have sounded bitter; instead, it mostly came off as wry humor.

“I thought Gaby was taking care of her.” The elevator doors opened and I stepped in and aside.

Lupe joined me. “She is. But we spell each other a bit on weekends. She looks after my chavos, and I manage Abuela.”

I pushed the button for the first floor, where I knew there was a small cafe. “How many kids – and, you know, names? Ages? The important stuff.”

“Four.” Her smile was brief – gone almost before it arrived. “Los cuatro demonios. My oldest, Miguel, is nine, Santino is seven. I got a little break before Andrea arrived; she’s four. My youngest, Matías, came just eleven months later.”

Her tone was light enough, but all the hints were there – the “four demons” was humor with a touch of truth; the three year gap between Santino and her daughter was a “break;” the last came “just” eleven months later.

“You must be exhausted.”

She shrugged. “It is what it is.”

We stepped off the elevator and headed for the cafe – called, appropriately enough, “The Atrium,” which was on the other side of the lobby. “It’s just hard for me to wrap my head around it,” I confessed. “Last time I saw you, we were 17, and your parents weren’t even letting you date.”

“Last time I saw you,” she countered, “You were the embarrassing nerdy cousin.”

I added what she’d been careful to leave out. “The one who was also, as far as anyone knew, male.”

She nodded. “Yeah, though . . . I’ll be honest, no-one was real impressed with your male-ness.”

“My cousin, the Queen of Central Valley High.” I smiled. “Yeah, I’m sure I was an embarrassment!”

She touched my arm. “For what it’s worth . . . I’m sorry. I was a bitch, back then.”

As we walked into the cafe I guided her to a booth and made her sit. “I’ll get it. What would you like?”

“Something sweet. I don’t care.” She wagged a finger at me. “I know what you’re thinking – I don’t need it!”

“I was not!”

“Well, whatever. But if they’ve got something like a caramel frappaccino with whipped cream, I’ll take it.”

I went to the counter and ordered, remaining until the barista had done her thing. Just the sound of the sugary concoction Lupe wanted had pushed me towards a plain coffee with a little skim milk. I wasn’t usually that fastidious. I brought the drinks back and sat.

Lupe looked at my spartan version of coffee and smiled sadly. “We should switch. I know it. I need to lose sixty pounds, and you could take all of them without any problem.”

“For whatever it’s worth,” I said, pausing to blow on my drink, “I strongly recommend against starvation diets.” A tiny sip told me it was still too hot. “Never mind about all that. You’re married, you have four kids. Gaby mentioned that you work in a day care during the week. So . . . How are you?”

“Tired, mostly.” She took a longish sip from her drink, eying me thoughtfully.

“What?”

“Can I tell you something?”

I nodded, feeling a bit apprehensive.

“When I saw you last week, after all these years . . . when I saw your face? I thought to myself, ‘that’s someone who’s been through a lot.’ It’s what I see, when I look in the mirror.” She closed her eyes, as if in pain. “It’s why I eat and eat. Why I’m wearing pinche size eighteen or whatever it is today.”

I was surprised to find my heart going out to her. It’s not that I hadn’t liked her when we were in middle school and high school. Not exactly. She’d just belonged to a whole different social order. “Hey,” I said softly. I put my hands on the table.

She opened her eyes and looked down at my upturned palms, weighing the invitation; her expression blended memories, questions, and all the hesitations both tend to generate. But after a moment, she sighed and placed her hands in mine.

I said, “I know we didn’t have a great relationship, back when. I thought you were just a stuck-up high school queen. But you know what really floored me, when I saw you last week?”

“That I look like a blimp?”

“Not that, no. It’s that you called me by my name, even when your mother was condemning me to hell. When you looked at me, I saw compassion, not disgust. And I realized that I was the real bitch, because I’d misjudged you all along.”

“No, you didn’t.” She squeezed my hands, released them, and sighed. “I was a stuck-up high school queen. I did look down on you for being different. If I’d had any idea you were trans, I would have been as much of a turd about it as anyone. But . . . Yeah. That’s not who I am, anymore.”

It felt like she wanted to talk, so I simply asked, “What happened?”

“Life, I guess.” Then she shook her head. “Well . . . that sounds like shit just happened, and that’s not how it was. You remember Andy Whitethorn?”

“Since I was forced to attend pep rallies and cheer on our mighty football team, I certainly remember the quarterback.”

She giggled. “I never thought of it like that. Of course, pep rallies were always like star appearances for the cheerleaders.”

“It’s what everyone watched, anyway. Even the girls – though in their case, it was jealousy.”

“Which was it, for you?” Before I could respond, she said, “Nevermind. Forget I asked that.”

“No hay bronca.” I smiled. “For the record, yes, I was jealous. Now . . . Andy?”

She grinned sheepishly, then turned serious. “I crushed on him so hard . . . and he felt the same way. But my parents wouldn’t let me date. Wouldn’t let me go to homecoming, or prom. Mamá said they were just ‘invitations to sin.’”

I nodded sympathetically, not wanting to provide my own opinion of Aunt Maria in any sort of detail. Nor did I want to mention that I hadn’t gotten any of those “invitations” either!

“When I had my Quinceañera, they wouldn’t even let me invite him. You know why?”

“Because he was a human male and you were crushing on him?”

“No.” She took an angry gulp from her coffee. “They wouldn’t let me date in high school, but they weren’t stupid. They know what the Quinceañera’s all about. But they only wanted me looking at ‘good’ boys. Boys from ‘traditional families.’”

I had been at Lupe’s Quinceañera, of course; all the family were always invited. Lupe had been an absolute vision in silk, lace and taffeta; naturally, she’d been surrounded by every eligible wey within sixty miles (and more than a few who definitely weren’t eligible). But . . . no question, the gathering had a certain cultural uniformity to it. “Andy was pretty Anglo,” I commented.

“He was a good guy, Carmen! He was handsome, and tall, and really, really, nice. Never pushy. Never tried to . . . well, you know. Even when I wanted him too! ’Cuz he knew I’d be in trouble.” All these years later, the raw pain in her voice was still acute. “But he was white, and he was Protestant. So he wasn’t good enough.”

She sniffed, then gave me an apologetic look before dabbing her eyes. “Sorry!”

“It’s okay,” I assured her.

“After graduation, he wanted to elope. And stupid me, I said ‘no.’ I wanted all the bells and whistles, you know? My padre walking me down the aisle – the kneeling pillows, the lasso, Las Arras Matrimoniales – all of it.” She shook her head. “¡Qué idiota fuí!, right? I thought we could convince padre – that he would see how much we loved each other. How good we’d both been, all through high school.”

Naturally, their “plan” worked about as well as any adolescent scheme. Her parents hadn’t understood at all; they’d grounded her and convinced her that she didn’t know her own heart. Pretty soon she found herself married off to one of those “nice, traditional boys,” in a big wedding that had all the bells and whistles . . . and none of the joy.

Luis was, by her own description, a decent man. Hard-working, even-tempered. Not given to drinking, gambling, drugs. He wanted his home to be clean, peaceful, quiet, and unstressful . . . and, at the very same time, stuffed to the ceiling with children. Reconciling those conflicting desires fell to Lupe.

Once she got going, Lupe was surprisingly – even shockingly – open with me. Maybe it was precisely because we hadn’t seen each other in so long. But she trusted me with things I would be reluctant to share with my closest friends. For instance, she said that after all the restraint her parents had imposed and all the lectures about “saving herself for her husband,” she’d found sex to be a complete nothingburger. She confessed, “I don’t even get it.”

Luis, on the other hand, was apparently more than happy to have sex whether she was a size two or a size twenty. He was “attentive,” and after all he wanted his chavos. But at some point all the work of keeping fit and trim just seemed like a waste to her. “I might as well have a frappaccino. It’s not like I’ve got time to work out, anyhow.”

As we were dropping our to-go cups in the trash, she said, “Back in high school, I thought I was somebody. And I thought life would be like that, forever. Loco, right?” She shook her head. “Now, I’m on my feet for sixteen, eighteen hours every day, and it feels like there’s no stop to it. I love my babies. I really do. I could never leave them. I couldn’t do what your mamá did to you and Ximo. But I have to tell you, there are some days . . . I can at least understand it.”

I didn’t know quite what to say to that. But I told her that she should take some time for herself, and I would deal with Abuela and make sure she got back to her house. “Don’t you be rushing back to spell Gaby!”

“Okay, I won’t,” she laughed. Unexpectedly, she gave me a big hug and even a kiss on the cheek. “Sorry to dump all that on you. I guess I really needed to talk!”

Her steps seemed a little lighter as she left. Mine, on the other hand, were slower. She’d given me a lot to think about.

Abuela, unsurprisingly, was right where I had left her. She sat, motionless, her head bowed, to all appearances deep in thought. Again I was struck by her stillness. It was so unlike the woman I remembered.

Her eyes swept the room and spotted us; fresh meat. “Carlos. Kelsey. You need to go upstairs and help pack up the chavalos’ room. Clothes first — use the laundry baskets. And no wasting space — fold everything!”

Emilina, eleven to our nine, piped up. “I can help, Abuela.”

“No; I need you to help your madre and tia Maria in the kitchen.”

“But—“

“Go, child! There is no time for arguing!”

Uncle Augui stepped through the front door of the big house — the one tio Javier and tia Juana needed to vacate when it became clear that his disability payments wouldn’t begin to cover his lost wages. “The truck’s running, mamá. We’re ready.”

“Bueno. Juan’s out back. Have him help you with the living room furniture.”

“Sí, mamá.”

Kelsey and I made our way upstairs, listening to the sounds of organized chaos all around us. She squeezed my shoulder. “At least we didn’t get Innie’s job.”

“Yeah.” I was trying to keep myself from crying. Mom and little Domingo had vanished a year earlier, and I was beginning to understand at a deep level that life was always uncertain. Things that seemed established were tentative; things that appeared strong were fragile. Like tio Javi, always the strongest of the brothers. I shook when I remembered how he looked in that hospital bed. Shattered. Pale, like an Anglo.

We got to work; Abuela insisted on results. We could hear her downstairs; it seemed like she was everywhere all at once. Everyone came to her for directions.

There was a spike of noise coming from the room down the hall which tio Javier’s older two, Alejandro and Jesus, shared. Innie had been tasked with keeping the little ones occupied, but even backed by Abuela’s authority she couldn’t handle seven. “AJ! Get back here!”

Kels sprang for the door but she was too late to stop Alejandro from making a break for the stairs.

“No! No! I won’t!” He was screaming — shrieking, even. “I want mamá NOW!”

But he was blocked from charging down the stairs by Abuela, who was coming up. She grabbed both of his arms and pinned him. “Stop!”

“I want mamá!”

She saw Kels and me in the doorway. “The chavalos’ room will wait. You both need to help Inés.” Looking down at the flailing eight-year old, she said, “Stop thrashing. Now.” Her voice was calm — almost frighteningly calm.

He froze.

“Alejandro, right now, your Papa needs your mamá, and she needs all of us. You are her eldest. She needs you most of all.”

He sniffed “Sí, ’buela.”

“Can you help Inés look after Joanna and your brothers?”

“Sí.”

“Good.” She released his arms. “Go with Kelsey and Carlos now.” Raising her voice, she called downstairs, “Fernando? You need to start with the big bedroom. I’ll pack up for the little ones.”

“Sí, sí, mamá.”

Kels was leading AJ back to the other room, but I lingered for a moment.

“¿Abuela?”

She paused and looked at me. “¿Qué?”

“Todo va estar bien?”

“Las cosas serán bien si las hacemos bien. No hay otra manera.”

Things will be okay if we make them okay – that was definitely the Abuela I remembered. It’s what made her silence and stillness in the face of padre’s stroke so difficult to process. But while her methods had changed, the important thing hadn’t; not really.

She was still making things happen.

I pulled up the chair from the monitor area and sat. “I told Lupe I’d bring you home when you’re ready.”

She nodded, but otherwise didn’t respond.

I decided I didn’t need to fill the silence. I was more than happy for some time to gather my thoughts, so I closed my eyes and proceeded to try.

After five minutes or so, she said, “Do you really think he can hear what we are saying?”

“I doubt it.” I didn’t bother opening my eyes.

“But you tell him stories anyway?”

“Why not? I might be wrong.” I wasn’t going to mention my thought that I might never get another chance.

“You want him to know,” she asserted.

“I guess so. As you keep reminding me, he’s my padre, so he should know. He should want to know.”

“You think so? I never heard from my padre after we moved here. He gave me a blessing when I left. Said he would keep me in his daily prayers. I didn’t expect more.”

She didn’t mention it, but her experience with her husband could not have improved her general view of what to expect of padres. Of the five sons she had given Domingo Morales, one was in prison and another had been horribly injured. Now her youngest was in a coma from which he seemed unlikely to recover. Domingo, who’d returned to Oaxaca when my padre was an infant, knew none of it.

But I was right about this. I was. “I didn’t say that he would want to know. Only that he should.”

“Sometimes, it would be a mercy not to know the details of our children’s lives.” Her voice was bitter.

“Maybe,” I conceded, keeping my tone even. “But if it would hurt him to find out that I survived – however I managed it – then I’m not sure why I should be merciful.”

She sat with that for a bit. Eventually I heard her stir, and opened my eyes to see her settling back into the chair. When she was comfortable, she said, “Well. Go ahead.”

“I’m sorry?”

“Finish your story. Maybe I should hear it, too.”

That . . . really didn’t sound like something I wanted to do. “I thought you and I weren’t going to talk about my life,” I countered.

She brushed that aside. “I did not want to hear excuses for why you won’t help your padre. I still don’t. But this?” she challenged. “You are just entertaining him, yes?”

“Educating.”

“And you think I would not profit from your ‘education’?” When I didn’t answer, she turned her head to face me. “I am your abuela. Shouldn’t I know, too?”

“Maybe. But do you want to?” If she could fight with my words, I could fight with hers. “Isn’t this one of those circumstances when not knowing would be a ‘mercy’ for you?”

“So now you want to show me mercy? The old woman who wouldn’t lift a finger to save you?” She laughed, soft and dry. “Try again.”

“Fine.” The truth hurt, but there was no point trying to hide it from the pinche witch. “I am not going to spill my guts out, just to have you mock me. How’s that?”

“And so you share your story with someone who can’t speak – and probably can’t hear.” She smiled slightly. “Alright. A truth for a truth. I’m not sure I want to hear your story. I doubt I’ll understand it. But you should still tell me.”

I couldn’t help myself. “Why?”

“Because you succeeded where your padre failed. I want to understand it.”

“I ‘succeeded’? Just because I got a degree, and padre worked in the fields?”

“No!” She heard the anger in my voice and understood it immediately. “Angel works in the fields. Augustin works in the fields. Javier was a mechanic. All of them . . . they all succeeded. They found their place. Where they fit.”

She patted the bed beside her. “Juan, though . . . he never did. When he was young, everything came easily to him — school, sports, friends. He could do anything. Could have done anything. You had his brains, but as far as I could tell, you were soft. Weak.” She shrugged. “I was wrong.”

Abuela’s almost casual admission left me speechless. In all the years I had known her, she had never admitted to either error or doubt.

She wasn’t finished. “For him, I did everything a madre could do – so much, that some of your tios felt slighted. When he left, I had no reason to think he would fail. For you, though? I stood by, and allowed him to push you away. When you left, you had no prospects for success. But he came back defeated, and never got up again. You didn’t.”

“I came back a basket case!”

“Don’t be a tonta. If you were a ‘basket case,’ I would not have asked for your help. You have scars. I can’t see them, but I hear them in every word you speak. Bueno. So do I. So does everyone. Adults learn how to deal with them, and Juan never grew up.”

It occurred to me, with all the sudden shock of a thunderclap, that I was having an adult conversation with Abuela. That she was treating me like I mattered. I had no idea why; I wasn’t sure whether I’d heard her treat anyone that way. I couldn’t wrap my head around it.

And so, however reluctantly, however haltingly, I found myself telling my story yet again. Abuela said very little, mostly letting me go on without interruption. When she asked a question, it was because I was glossing over something important. She didn’t flinch from hearing about my time on the street, even when I told her about stealing food and clothes, or going crazy.

For some reason, I was reluctant to tell Abuela much about Sister Catalina. Maybe those memories were too private, or too sacred. Maybe it still hurt too much. But she pulled the story out of me, and it was one of the few things I related that genuinely surprised her. When I asked why, she said, “I’m from Oaxaca. You can believe in the Trinity, and still see the church is a den of thieves.”

I left out a lot of detail. There were plenty of stories that I would blush to tell Abuela, though alone with padre – while he remained comatose! – I might still share them. Even my summary took over an hour. At the end, I suppose I expected something like a judgment.

She didn’t oblige, naturally. “So . . . this law degree. You will get it, when?”

“Three more semesters, I hope. A year and a half.”

“And then you will be an abogada?”

“I’ll have to pass a big test first. It takes three days.”

“You will pass.”

“Almost half the people who take it don’t,” I warned. The California Bar Exam was one of the many things that kept me up at night – though I did try to use my insomnia to squeeze in some extra hours of study. The possibility that I might fail, after working for years to get my degree, was terrifying.

“You will pass,” she repeated, with certainty I wished I could share. Seizing the arms of the chair, she rose to her feet. “Come. It’s time to leave.”

I led her down to the lobby and out to where I’d parked the Kia. She was silent on the drive, apparently deep in thought.

I was trying to thread together the two very different conversations I’d had that day. Tentatively, I said, “I had a good talk with Lupe.”

She grunted an acknowledgement, giving me no help.

I tried again. “She’s finding it hard, with the four chavos.”

“Angel and Maria spoiled that one, and she was too pretty for her own good.” She shook her head. “Life hit her hard, and she had to grow up fast. Maybe too fast.”

“I’ve been thinking about something she said. . . . How she could never leave her babies, like my mother did. But she could at least understand it.”

“Your mother wasn’t hard to understand.” Her voice was even more dry than usual.

“You didn’t run away. And you had even less help that Lupe does – or than my mother did.”

She snorted. “I grew up dirt-poor and Domingo did not marry me for my looks. I wasn’t raised on lies about ‘love’ and ‘romance.’ My madre told me that life was work and work was hard, so I wasn’t surprised like Lupe or Kathy.”

We lapsed back into silence until we were in Buttonwillow proper. As we turned down Abuela’s street, I said, “There’s something that hasn’t changed – Sunday in June, and Uncle Angel and Aunt Maria are having a pool party.”

“Are they?” She sounded surprisingly interested.

“Couple extra cars at their house,” I confirmed.

She spoke abruptly. “Describe them.”

“Why?”

“Because I’m curious.”

“Umm . . . a small blue car . . . an old red pickup . . . a big white van?”

She was nodding. “Stop the car.”

I pulled over, curious. “What is it?”

“I think mi hijo forgot to invite me to his party,” she said, amused. “But that’s alright. I will surprise him.”

“Okay, Abuela . . . what’s going on?”

“When you are blind, people often think that you are both deaf and stupid, too. Your cousin Gaby often makes this mistake.”

Her non sequitur left me floundering. “Huh?”

“Just walk me to the back. It will be clear enough when we get there.”

I did what she asked, all the while trying to work out what was going on. She must have overheard Gaby talking to someone – almost certainly Aunt Maria – about something.

I could hear their voices as we walked down the concrete path that went along the side of the house. Animated voices. Contentious voices.

And I recognized every single one of them.

All sound ceased the instant we came around the corner, and seven sets of guilty – or at least surprised – eyes turned to see us. With a nudge of her bony hand, Abuela kept us moving, right up to the sitting area by the pool. She barely needed my guidance, stopping right at the correct spot and staring at the plastic faux-Adironack chair my senior uncle occupied. “Well, Angel? No welcome for your madre?” Her head turned a fraction to the left. “No kiss of greeting, Maria?” She continued the pivot. “Augustin? Javi? Daughters? Are you not glad to see me?”

She urged me forward into the silence, moving directly toward the seat occupied by Angel and Maria’s son Francisco, the only member of my generation present.

Seeing the direction of her progress, he vacated the seat quick as a jackrabbit who’s seen the shadow of a hawk.

I helped her into the chair. It was plastic, but unlike the Adirondack it allowed her to sit firmly upright. Her thin fingers curled around the ends of the arm rests, giving the impression of a queen holding court.

“So you want to discuss Juan’s conservatorship? Bueno. By all means, share your opinions. Don’t hold back. Say what you are thinking.” Her unseeing eyes turned hard as she unerringly directed them to the seat where Aunt Maria was frozen in place.

“Say it now. Say it to my face! . . . And to Carmen’s.”

— To be continued

For information about my other stories, please check out my author's page.

If you liked this post, you can leave a comment and/or a kudos!

Click the Thumbs Up! button below to leave the author a kudos:

And please, remember to comment, too! Thanks.

Comments

A truth for a truth...

It occurred to me, with all the sudden shock of a thunderclap, that I was having an adult conversation with Abuela. That she was treating me like I mattered. I had no idea why; I wasn’t sure whether I’d heard her treat anyone that way. I couldn’t wrap my head around it.

From an unexpected source comes the beginnings of understanding. Not just for Abuela but for Carmen. Abuela admitted that she does not understand Carmen; but this exchange indicates she is willing to try, perhaps.

And maybe there is a remaining part of Carmen that needs convincing herself to believe she matters?

Love, Andrea Lena

The way back from hell . . . .

When someone you love tells you to go to hell, you generally make the trip. And the road from hell is paved with false starts, side trails that lead to dead ends, and a keg of regrets. Has Carmen made it all the way back yet?

Does anyone, ever?

Thank you for your insightful comment, 'Drea.

— Emma

“Say it now. Say it to my face! . . . And to Carmen’s.”

cool!

And, at the same time . . .

. . . scorching hot! I would not want that woman mad at me!

Thanks, Dot!

— Emma

Perhaps the best closing word

Of any chapter of anything I’ve read on the site.

Names matter

Sometimes, they matter a whole lot.

Thanks, cattherd. :)

— Emma

What changed? Several things

What changed? Several things changed..Carmen shared her life after she left. Abuela listened to a young woman describe the hell she faced and overcame the abyss. A young woman banished from family made her life in the direction she wanted by grit and determination despite the overwhelming odds.

Abuela understands as she herself said she came from poor family was married not for love but by parents choice. Told to work hard after the marriage. If anyone could understand what Carmen went through to be where she was now as a budding attorney after all she had to go through, Abuela could.

“So you want to discuss Juan’s conservatorship? Anyone else understand there wouldn't be a conversation if one or two things weren't involved, either money or property or both. Otherwise they would be discussing who they could foster it off on while washing their hands of the whole mess. Basically, we are doing it. End of discussion.

Hugs Emma, still has a vicious bite to the story. Too close to life to be a story. Superb writing skills.

Barb

The last one surviving, turn out the lights.

Oklahoma born and raised cowgirl

The kinship of suffering

The chapter illustrates how suffering can create, or at least foster, a capacity for empathy that might or might not have existed otherwise. Lupe and Carmen see it in each other. Abuela's connection to Carmen, tenuous as it appears, seems to be built on a recognition of, and respect for, the hardships Carmen endured -- hardships which, as you note, Abuela is probably better able to understand than most of the people in the family. Although maybe not all of them. ;-)

As for why other members of the family might concern themselves with Abuela's idea of appointing Carmen as conservator, I think you may be missing an explanation that might be simpler still. But . . . you'll need to wait a week to find out if I'm right about that . . . .

Thansk, BarbieLee!

— Emma

Not deaf or stupid

And still very much the matriarch of her family. Abuela is about to dissect the conspiracy they were trying to leave her out of. As the saying goes; heads will roll.

Note: she said,

Carmen... no mention of her dead name.

Hugs

Patricia

Happiness is being all dressed up and HAVING some place to go.

Semper in femineo gerunt

Ich bin ein femininer Mann

Oh, yes!

Abuela's comment about how people tend to tune out blind people is absolutely true -- and even more true, I think, of the deaf. But you've gotta be some special kind of stupid to think that old pitcher's lost anything off her fastball!

Thanks, Patricia!

— Emma

All politics begin at home………

And there is nothing quite as vicious as family politics!

Carmen’s Abuela has caught her children conspiring against her and her wishes, and based on her accusatory comments to Maria, it is obvious who she believes is the instigator - the main conspirator if you will. From what I have read, I am not surprised. Maria seems to be a major bitch, and most of the men seem to be afraid to stand up to anyone.

Interesting that Maria’s son Francisco is the only cousin present. I wonder what that heralds? Are they planning on pushing to make him conservator?

And how does Carmen play into this? Is this all about Maria not wanting Carmen involved? Or even around?

Carmen’s Abuela maybe a bitch, but she is also willing to work with Carmen. She may not be totally accepting of Carmen as she is, but along with a few of Carmen’s cousins, she is willing to treat her like an adult - and not some abomination. Not something to be scraped off your shoe. Simply being treated like an adult, like a person, is a victory for Carmen.

D. Eden

“Hier stehe ich; ich kann nicht anders. Gott helfe mir.”

Dum Vivimus, Vivamus

Carmen the only fit conservator?

Certainly almost anyone could be the conservator, but the Abuela must see that Carmen is probably the only one who won't approach the job with her own interests in mind.

Carmen also knows what needs to be done.

Abuela is practical, and she understands the implications of Juan not having insurance. Carmen knows how to navigate that bureaucracy; the rest of her family, not so much.

— Emma

It completely disarmed her.

Carmen wasn't at all keen to share her story with Abuela. But when Abuela treated her like an adult -- when she was willing to say that she, the goddess-like Matriarch, had misjudged Carmen and mishandled Juan -- Carmen was completely disarmed. She opened up. I tell you . . . the old woman gets people. She understands what makes them tick. And she knows just how to get what she wants!

Thanks, Dallas!

— Emma

Abuela

Tough old bird to say the least, definitely one only good enough to make soup out of as she would be too old/tough for anything else.

So apparently she only respects strength and as one who has transitioned in difficult (not as hard as hers or Carmen's gratefully! Raising a large family on so little is tough! As a first gen American I know) times we all know it takes a will of iron (and an extremely large helping of luck!) to get through it especially for all those who did so in the seventies and eighties or earlier.

So now she belongs to that exclusive club of her family who has faced the fiery forge of life and came away singed but stronger.

Abuela must feel that Carmen has what the family will need to keep it moving forward like she has done. Juan should've done it if only he had not wasted all of his potential.

Interesting turn of events to say the least.

She might need to go to the glue factory!

But she'll save her family first, if that can be accomplished by force of will.

I think you've got a good read on her character, Kimmie. People who've had a life like Abuela's don't tend to be sentimental types, and she's definitively not.

Thank you, as always, for your thoughtful comment!

— Emma

Character

Thx.

I hesitated to bring up a severe weakness though in that she was stilll unable to pull away from her Catholic faith and not have birth control.

There is nothing explicit in the Christian faith that forbids birth control as far as I know but I think Catholicism just wants as many followers as they can get to keep them in business to be frank about it.

Finally, Abuela was kicking the tires here, she wanted Carmen's story as sort of a job interview, nothing more.

Now, whether the respect Carmen has received is enough to warm her up to the idea of being next head of family is another matter.

I wouldn't want to do it, it is a thankless job by a bunch of folks a lot of whom don't even like her. Just because they are family means they should be supported does not cut it with me, they have to care for me also.

I was very lucky in my partner in that she had a family that still interacted with her and loved her, though her mental illness and alcoholism did dim that quite a bit.

However, they continue to be accepting of me and got invited to Thanksgiving last year by one of my partner's nieces whom also is my heir at this point.

My brother OTOH only wants me to toe the same political line he does, does not see how bad his right wing views (straight out of Faux news and NY Pest, he would always send me links to them in his emails!) has a bad impact on me, pooh poohing my concerns.

To his credit he has not disowned me as a sibling but we don't talk anymore or get together.

Anyway, family, or is it Family in this case while important should never be everything.

Probably more cultural than religious.

Abuela was born in Oaxaca in the late 1940s. I doubt she gave a lot of thought to the path her life would take, in terms of marriage and children. It's just what you did. However, she was the one (as Carmen relates in Chapter 1) who dragged her husband out of Oaxaca so that their children were all born in California. So I'd say she didn't have an issue with the "family and kids" thing, but she wanted to make sure that any offspring had the best chance in life that was possible at the time.

I don't know if the job interview framing is right. More often than not, when the matriarch passes, the children become the heads of their own family groups. Maybe Abuela just wants to make sure Juan is taken care of. Maybe she wants Carmen back in the fold, too. It could be a latent Catholic sentiment working there. To quote John 18:9, “I have not lost any of the ones you gave me.” That definitely sounds like the sort of sentiment Abuela might harbor.

I'm glad that your partner's family makes room for you, when your own is distant. You remind me of something I read recently. A reporter was talking to someone from one of the Baltic states, who told him that they think of Finns as friends and Russians as family. When the reporter asked why, the man said, "You can choose your friends."

— Emma

Dragging the story out of Carmen

Then why bother dragging that story out of Carmen.

Morbid curiosity? Even if Carmen is doing poorly I doubt Abuela, given how she let Carmen get kicked out, would offer to bring her back to take care of her.

Carmen can never come back, the conservative hooples in that community would make her life a misery.

Make sure Carmen is okay and that she can make it on her own ?

At what point does Abuela is finally willing to let go and let her progeny decide their own fates ? Why be a matriarch at all ?

Abuela really does not need to know how Carmen made (unmade ?) the sausage despite starting from literally nothing in the big bad world.

My brother certainly did not ask how I navigated and succeeded in my transition. I don't know whether he just expected it or he just does not care. Or he is just clueless and does not understand how difficult it is.

So, no, Abuela did not need to know Carmen's full story. A one liner indicating she is on track to be a lawyer should be sufficient that should already speak volumes. Maybe to assuage the guilt she felt in letting Carmen get kicked out ?

Actually . . .

The reason she gives Carmen in the text of this chapter doesn’t strike me as implausible. More may bubble to the surface, of course. She is what a character in a Patrick O’Brien novel might call a”deep file.”

— Emma

nothing explicit in the Christian faith... forbids birth control

I married a Catholic girl and did some study on the basis some odd points in their theology.

Forbidding birth control is based on an obscure Old Testament story about a childless widow's brother-in-law not wanting to fulfill the custom of marrying the childless widow and providing offspring to continue his bother's line. (Not sure just how that works LOL) While he did marry her and have sex with her he pulled out and "spilled his seed" and that so angered God that he died, The Catholic church grabbed onto that and extrapolated it to mean, it's against God's will to have sex without trying to procreate. This is not something that is backed up anywhere else in the Bible.

Thankfully my wife was just enough of a rebel to not buy into it and took birth control. We did have two and decided that was enough I got a vasectomy. She then heard horror stories about vasectomies failing and decided she needed a tubal ligation.

Hugs

Patricia

Happiness is being all dressed up and HAVING some place to go.

Semper in femineo gerunt

Ich bin ein femininer Mann

I can’t dunk too hard on the rhythm method.

I wouldn’t exit without it. Oopsie! ;-)

— Emma

Tough to find...

A story with such real life characters that bristle and shine in every word they speak, their thoughts, their motivations - hidden or not, and how intertwined they are. This is absolutely your best work to date! 100%! Thank you for sharing!

XOXOXO

Rachel M. Moore...

"Bristle and shine."

I like the sound of that -- like it a lot!

Is it my best work? I'm too close to tell. I think in some ways it's my most ambitious work -- and hey, I did a humorous novel with space aliens and crazy Russians!

— Emma

Respect

Abuela is a hard bitch who has little room for love in her heart, but she finally seems to come to respect Carmen.

A bit of love - or even affection - would be nice, but too much to hope for. Respect for Carmen's strength of character is a huge step forward, and more than Carmen could have dreamed of.

Who would have thought that this old dog (bitch!) could have learned a new trick?

“Do you love me?”

I put that in quotes, because I’m thinking of the song from Fiddler on the Roof, where Golda sings,

I think Abuela is very much in that camp. If someone were to ask if she loved Juan, or Carmen, or any of her offspring, she would wave off the question as useless. Stupid. I doubt she gave Juan — her favorite son, whether she’d say so or not! — a kind word. But she was always there for him, and is still fighting for him as best she can.

Thanks, Alison!

— Emma

That Last Word

"Carmen"!.

Not approval, but acceptance and the realization that Carmen is the only one with enough iron in her to impose a solution that satisfies Abuela in her dealings with the offspring and family that think they can discard and ignore her now that she is old and blind.

The real kicker is that there is little to share when all their lives have been essentially wasted. Lupe's story of love lost and family pressure encapsulates the limited horizons of their community, especially for the girls.

Wasted

Maybe not for all, she considered some of them only reaching what they were capable of. Working in the fields are a low bar but at least that is available.

She realizes despite her being trans she is the best of the generation. For a Catholic though it must sadden her that Carmen cannot have progeny unless Carmen had foresight to sock some away.

In theory Carmen's brother might have the same potential but needs a second chance to realize it and thus carry on Juan's potential also.

I wonder.

I never really thought about the whole “great grandchildren” issue. My gut reaction is that it’s the sort of problem Abuela would regard as too theoretical to bother about. Children show up; someone needs to raise and take care of them. Get them to adulthood. Lather, rinse, repeat. She has children and grandchildren, so she tries to take care of them, but she doesn’t seem like the sort to think about generations yet unborn.

Maybe I’m wrong. Abuela’s “voice” feels very strongly to me when I’m writing a scene with her in it, but I’ve never tried to write a scene where that issue would come up. If I do, we’ll see how it goes!

— Emma

Not approval, but acceptance.

I think that’s probably right. Abuela is upfront in saying that she can’t really understand why Carmen did what she did. But she operates a number of different levels. In a hard, practical way, she isn’t one to discard a tool because she doesn’t care for the design. But at a deeper, more human level, she does not cut off any of her offspring. Not Juan, even after all his disappointing failures to live up to his potential. Not Kelsey, when Fernando was arrested and lost their house. And not Carmen — though she would not intervene with Juan.

As for Lupe . . . I think her story is not so very different from many very pretty girls who peak in high school. There’s a lot of life to get through, if it’s downhill from 18! I always think of that line from an old Paul Simon song, where he describes Lorelie, the girlfriend of a navy man stationed in Newport News as “a high school queen with nothing really left to lose.”

Thanks, Jo!

— Emma

Another such song: “Drive-in Movies and Dashboard Lights”

Great song by Nanci Griffith. There are many others but that’d be my favorite.

"... and to Carmen's"

This seems to be a serious turning point -- Abuela treating Carmen like a fellow adult. That's big. I remember when my father started talking to me that way. Some of my siblings never got that, and don't believe me when I describe it, but it's a huge thing. Respect.

And wow, does the Abuela have a knack for entrances. It's almost like Daredevil, what she does there. Slicing right to the bone -- pulling open the discussion and challenging everyone there.

Great chapter. Amazing world.

hugs and thanks,

- iolanthe

Respect

Yes! As I’ve written above, I think Abuela loves her offspring in her own, unsparing and wholly unsentimental way. But Carmen hasn’t actually heard her to speak to anyone else as an adult, even though Abuela views Angel, Augustin, and Javier as having succeeded at the task of life — the task being, as a Quaker might say, to “come down where you ought to be.”

As for entrances, I can’t tell you how much I enjoyed writing that scene. I’ve had it in my mind for several chapters now, and I had to wait! Abuela’s blindness is somewhat mitigated by the fact that she is living where she has been for fifty- plus years, and her adult children are creatures of habit. So she can picture in her mind exactly where everyone will be sitting, except for young Francisco. And her ability to power through like she has no disability at all gives her words an almost supernatural force.

So glad you are enjoying this!

— Emma

Abuela

Abuela is not only formidable, she’s one of your most memorable creations, Ms Tate, and with your gift for depth of characterisation, that’s really saying something. Steely, stubborn as a mule and with iron determination. Mutter Courage but in Spanish.

This is the first time that we, and Carmen, have learned anything significant about her married life and how it has shaped the woman that she has become, and it’s very revealing.

Not only that, she reveals it to Carmen, so when she makes her outburst at Maria’s party, yes, Carmen’s inclusion still comes as something of a surprise, but not entirely. There’s been a reconciliation, but Abuela will never tell Carmen that, of course.

Superb writing, Emma.

☠️

She steals every scene she’s in!

Honestly, I have such a clear picture of Abuela in my mind. I know this woman; I feel like I’ve always known her. It makes her a far easier character for me to write than almost anyone. And, no. She’s not going to get all gushy on Carmen. Especially when she’s figured out that Carmen thrived — in Abuela’s utilitarian view of that term! — through adversity.

— Emma

Once again...

I think in many ways Abuella has come to respect Carmen as a woman. She might not admit it as such, but the language change and behavior shift is notable... she respects that she made something of herself, and unlike Calos... who ran, who gave up... Carmen stands up. A powerful woman respects a powerful woman... and power isn't always overt, or masculine or aggressive... sometimes its an inner strength, a survival instinct.

God, this book is fantastic Emma, brava.

I like Turtles.

I agree

When Abuela tells Carmen that she’s an adult in a way that Juan never managed to be, that sounds like respect to me — even if Abuela never uses the word.

Thank you for your kind comment, Alyssa!

— Emma

The Roads Not Taken

Having returned in strength, with new life constructed, and developed determination solid, Carmen - out of all the other family we've seen - is therefore the most like her Abuela: proven capable to conquer hardship and true change. Others settled without striving for greater heights, never made the hard challenging choices. In this Abuela has begun to recognize that applied flame of spirit within her granddaughter, forged in painful fires but having held true.

At the heart of this tale lies those choices each have made, and the ones that they have allowed to linger even as the clocks and calendars slip forward in time's eternal momentum perceived first as slow until suddenly gathered in abundance behind. Magnificent characters, Emma. Simply magnificent.

And thinking about this chapter had me rereading a short yet rather famous poem:

Roads not taken

So well-said, as always, Seraph! Carmen’s story is necessarily interwoven with the story of her parents’ choices, and even her grandmother’s. Which, as Faulkner would tell us, is always the case.

I’ve always loved Frost’s poetry, and of course The Road Not Taken is a classic. He writes it from the perspective of the young man standing at the fork in the road, imagining how he will view the choice in years to come. How, if he prospers down the road he takes on essentially a coin-toss, he will valorize his choice. “Ah, it is because I dared to chart my own path! It is because I had courage! It is because I chose the road less traveled, that I have prospered while others have not!” Frost’s young man is wise beyond his years.

— Emma

The Eternal What If

Well, at least as far it is for trans people: What if we were born as we were supposed to be ?

Carmen clearly has not fully faced that reality in the context of her own (former) community until faced with a reality of it in the form of Lupe.

Carmen's road is/was hard but at the end of the road, you are who you are which in an ideal world would be your best self.

I have asked myself countless times in my life whether the price was worth it or not, always gnawing at my spirit yet time and again the answer is that it is what it is, it is neither better or worse than what it could've been, just different forms of growth and rewards and failures.

I chose the path of where my identity took me, a lonely place but then again I grew up pretty alone with only mostly my parents for people contact so I have the tools to deal with it. The cat helps too of course, but I've come to dread the compromise that is most of humanity and am loathe to let down my guard unless I know them really, really well so another partner/spouse in my life will probably never happen again.

Anyway, Carmen has hope yet though. By luck she has avoided Lupe's fate. Like her I like good children but it should not be the only thing in a women's life that she has to sacrifice everything for.

Closing doors

As we make our path through life, we close door after door of possibility. Some, we close early. As a simple example, I stopped studying math after my second year of high school. That decision obviously closed lots of different doors. It’s not the way I looked at it at the time, but it was still true.

For a trans person, the decision to live the truth you feel inside is maybe the largest one, because it closes lots of doors. Hopefully it opens others. Certainly both of those things were true for Carmen.

The end of all this door closing, though, isn’t a prison of your own making, or it shouldn’t be. What it is, is identity. We are the sum of our choices — and of our commitments. Who we could be is cabined by our DNA and, to a lesser extent, our environment. Who we are is a matter of our own choice.

— Emma

Quite the matriarch

So good to gain a better understanding of Abuela. Well done Emma.

>>> Kay

Definitely . . .

She is definitely one of the more interesting characters I've gotten to write.

— Emma