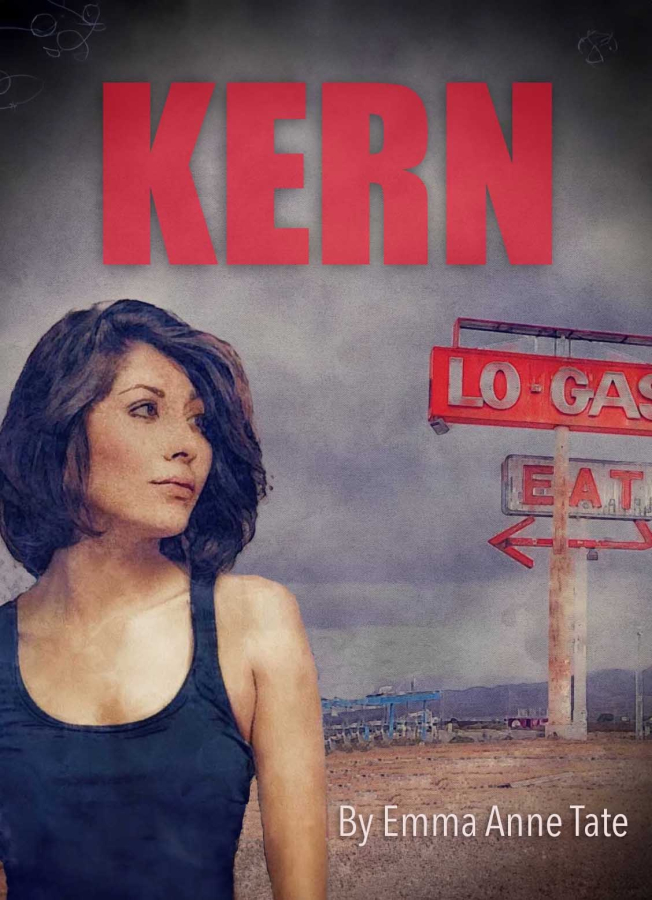

Carmen Morales is a twenty-nine-year-old transwoman who works for an insurance broker in Orange County while attending law school at night. She and her two roommates are celebrating the successful conclusion of her spring semester when she is summoned back to the Kern County home she was kicked out of eleven years before, by the Grandmother – “Abuela” – who refused to intervene. Her father has had a stroke and is in a coma. She spends several days there and reconnects with some members of her extended family – Abuela, her brother Joachim (“Ximo”), her uncle Augustin, her senior aunt Maria, and some of her cousins – Kelsey, Inés, Guadalupe, and Gabriella. None of the interactions are free of strain, but she succeeds in coming to terms with Ximo, Kels and Innie. And even, to a certain degree, with Abuela herself. Abuela convinces a very reluctant Carmen to apply to be temporary conservator for her father.

In Chapter 12, Carmen returns to Orange Country for three days to avoid taking too much time off from her job. Her roommates welcome her warmly, her boss is understanding. She quickly feels right at home and does not want to return to Buttonwillow. She is afraid she might start to care for the family that had rejected her. On the drive back, however, she stops by the gravesite of the woman who had rescued her from the streets of Los Angeles after she’d been homeless for a year – a woman who had never been afraid of caring.

Chapter 13: The Teacher

A minor accident on the Grapevine caused a forty-five minute delay in my journey – and a bit of worry in terms of the state of my gas tank. Fortunately, the gradient on the way down is so consistent that I was basically able to coast most of the rest of the way.

At Wheeler Ridge I switched from the Interstate to old U.S. Highway 99, having decided to get my stop at the hospital out of the way first. As far as I knew, there hadn’t been any changes in Padre’s condition, but I wanted the opportunity to get an in-person update. Since I was running on fumes – which really wasn’t like me – I got off at White Lane, coasting down the offramp into the waiting arms of a most-welcome gas station.

A bit after eleven I arrived at the hospital. I didn’t recognize the woman who was holding down the desk at the nurse’s station, so I identified myself and asked if there had been any change in Padre’s condition.

“I’m sorry, Hon,” she said sympathetically. “He’s still stable, but he hasn’t regained consciousness.” She checked something on the monitor on her desk and added, “Doctor Chatterji will be in at 1:30; I’m sure she could give you a more complete update.”

I thanked her and turned to go when she said, “Oh, there’s a gentleman visiting. He’s been there an hour or so, though, so I doubt he’ll stay much longer.”

I assumed it was one of the tio’s, though all but one of them would laugh at being called “gentlemen.” Probably either Uncle Angle and Uncle Augustin, since they both work during the week, and Saturday would be a logical time to pay respects. Uncle Fernando — Kelsey’s papí — was still in prison, and I knew tio Javier didn’t get out much. He’d been wheelchair-bound since he’d lost almost his entire left leg in a freak accident with a harvester twenty years before.

While I was eager to see Uncle Augui again, I was less wild about bumping into my senior uncle, who was always a bit too much under Aunt Maria’s thumb. My encounter with her the prior week demonstrated that her judgmental streak had only grown more pronounced with age.

As I approached Padre’s room, I heard a man’s voice, low but clear; it sounded like someone reading out loud rather than conversing. “While Engels thus expected that the Left’s enemies would launch a preemptive attack, he could not imagine in 1895 that this might win mass approval.” The material was dry, but the voice was warm, animated, cultured . . . and unmistakable.

That’s not one of the tio’s! I didn’t even need to see the eagle’s beak of a nose under his scholarly glasses. Without thinking how it might sound, I blurted out, “What are you doing here?”

He looked up, startled, and snapped his book closed as he rose. “Excuse me, young lady. I am –”

“Señor Olivares y Cortez.” He’d permitted the shorter form in the classroom, but the full formal address seemed more appropriate to the moment, somehow. “I know. I remember.”

He blinked in surprise, then smiled. “Someone has not forgotten her lessons! But, I fear you have me at a disadvantage. When I see former students outside of school, I sometimes struggle to . . . .”

He stuttered to a stop and his eyes widened. When he finally spoke again, his voice was reduced to the barest breath. “No.”

I felt a flash of impatience – and of anger. My own smile fell and I stiffened. “As a matter of fact, yes. Very much ‘yes.’ My name is Carmen Morales, now. And if I may repeat my question, what are you doing here?”

“Madre de Dios!” He shook his head slowly, like someone who’s been stunned. “I thought you were lost!” Coming out of his stupor, he took four steps forward and pulled me into a hug – somewhat awkward, since one of his hands still held a weighty hard-bound book.

I was stunned myself; señor Cortez had never been physically demonstrative. I hadn’t decided on a response before he pulled back.

“Forgive me,” he apologized. “You are here to see your padre, and I am interfering. But you must know I was extremely concerned when you disappeared. I asked your younger brother about it, but he simply said you were gone and would give no details.”

My anger vanished as quickly as a startled desert iguana. Grabbing his free hand in both of mine, I pressed it and said, “Please . . . you aren’t interfering at all. I’m delighted to see you. I just didn’t expect to see you here.”

“Well, Juan was one of my first students. Not to mention . . . .” Again he stopped, seeing my own look of surprise. “You knew this, surely?”

I shook my head and gave a wry smile. “Since neither of you ever saw fit to mention it to me, no!”

“For me, in a classroom setting, it would have been improper. But I would have thought . . . .” Again, his voice tapered off.

“Eventually,” I observed, “You’re going to have to start finishing your sentences.”

He sighed. “I should have known he would say nothing. Juan and I did not part on good terms.”

“We’ve got that in common,” I said dryly. “Let me check on him. If you have a few moments, I would really love to catch up.”

“Nothing would make me happier.” His response was formal – almost courtly. “Take as long as you like; I will be in the waiting room.”

I couldn’t resist teasing him. “I see you brought some light reading material.”

“But of course.” He held up the cover – Anatomy of Fascism. “I recommend it, Ms. Morales.”

“Let me guess – It’s going to be on the test.”

His smile was grim, and even that did not reach his dark eyes. “I fear it’s likely to be the test.”

On that note, he left.

I needed a little space to process señor Cortez’ surprising appearance, and I expected he needed a few minutes to process mine. I’d apparently done the equivalent of coming back from the dead, as a female no less; he just looked a bit older and even more distinguished.

To give us both time, I didn’t rush my examination of Padre. The man in the bed looked little different than he had when I had seen him Tuesday evening. Maybe the flesh around his neck and on his forearms looked a bit more drawn, but it was difficult to tell.

“I’m here,” I decided to inform him. “Did you miss me?

No response, naturally.

I sat in the chair that señor Cortez had vacated. I’d admired him tremendously, and It felt good – actually, extremely good – to know he’d noticed my disappearance and been concerned enough to ask my brother about it. He couldn’t have known that Ximo, an insecure 14-year-old at the time, would be the absolute last person to tell him what had actually happened to me.

“Well, apart from you, I suppose,” I said to my unresponsive father.

I sat with that for a moment, then decided, with a snort, that I was being stupid. My many issues with Padre weren’t going to be resolved by making snarky comments at his bedside while he was comatose. “But if you wake up, old man,” I growled, “you and I are going to talk.”

I went to meet my old teacher, and was unsurprised to find him deep in contemplation of the book he had been reading to Padre when I came in.

He rose gracefully and again shut the book, this time more gently. “So . . . ‘Carmen?’ That’s a lovely name. But of course I’m biased; my father was born in Seville!”

“I remember,” I replied, smiling. “You shared that with us, when you played bits from the opera as part of one of your lectures.”

“Ah, very good! ‘The rise of the proletarian consciousness and aesthetic in Nineteenth Century Europe.’” He looked pleased that I had recalled the lesson. “I had to drop that section a few years later; the administration made me cut out material that wasn’t on the standardized tests.”

“Are you still teaching?”

“To tell you true, after this last year I’m on the fence. But that’s a long tale, and I’d like to hear yours first.” He gave me a shrewd look. “I’m guessing you are only back for a visit?”

“I’m afraid that’s true.”

“Well, I’m sure you’re pressed for time, but . . . a body must eat. Can I persuade you to join me for lunch?”

I nodded enthusiastically. “Yes! I’d love that. I need to be back here at 1:30 or so to catch up with Padre’s doctor. That gives us a bit of time.”

“What kinds of food do you like?”

“I’m not picky – but all I remember of Bakersfield were the chains!”

“Ah . . . I think we can do better than that.” His eyes gleamed. “Do you trust me?”

I laughed, and somehow felt inspired to crook an elbow, like a fine lady in a period drama. “Lead on, sir!”

He took it without an instant’s hesitation and guided me out into the sunlight.

A few minutes later, we were seated in wicker-and-iron cafe chairs in a cool, darkened bistro. “I highly recommend the Cuban Sandwich,” he suggested. “Not to say there aren’t other wonderful things on the menu, but I can never resist it when I come in.”

We ordered two. I decided to stick with water, and he did the same. Once the waiter bustled off, señor Cortez leaned back and gave me a long look. “I have known your family for three decades. Your padre was one of my first students – and, in all my years of teaching, probably my best.” He grinned and waggled a finger at me. “Yes – even better than you, though you gave him a run for his money.”

“He was? I did?” I shook my head. “This just isn’t how the world ever felt, to me!”

“Not surprising. At that age, you could have no perspective.” His hand fluttered, dismissing the issue. “But the point I wished to make was different. I knew your father, and of course, when I was teaching him, I met mamá Santiago, your formidable abuela. I’ve taught your brother, and your cousins, and met most of your aunts and uncles. And on top of all of that, I have spent half my life in Kern County. Seeing you now, I think I know why you left – and why young Joaquim would not tell me anything.”

I lowered my eyes. “Yes.”

“I am sorry. Our community is not kind to people who don’t fit the mold; it is both the flip side and the downside of being ‘tight-knit.’ It must have been very hard for you.”

I decided I didn’t want to go into that, so I smiled instead. “You were one of the bright spots. I loved your classes.”

His eyes crinkled, suggesting that he saw through my efforts to turn the conversation toward less painful subjects. Still, like a gentleman, he played along. “I am glad. So, then. Tell me where you went, after leaving Kern County behind you? What are you doing with yourself?”

“I spent a couple years in LA trying to get my feet under me.” That’s one way to put it! “Then I caught a lucky break, moved down to Orange County, and started working for an insurance broker. I’m still there. But I did night school for six years and got my BA, and now I’m in law school at Western State.”

“Excellent! Outstanding!” He positively beamed. “Please tell me you took your degree in history?”

I shook my head, fondly. “I’m afraid not . . . though I did take a couple of courses. I have had to be more practical.”

“Business, then.”

“Yes, exactly.”

“And now, law? An abogada? I admire your ambition.”

“Remember, in U.S. History, when we were learning about the whole mythology around the ‘Lost Cause,’ and you showed us clips from Gone With the Wind?”

“Of course. Another segment I’ve had to drop.”

“I honestly hated the movie, but there’s a scene that stuck with me.”

He nodded with immediate understanding. “As God is my witness?”

“Right. I’ve known that feeling. When I left LA, I made the same vow. I won’t go hungry. Never again. And I’ll stand on my own feet.”

He laid a hand on top of mine and squeezed gently. “You have left many details out of your story. I assume you have good reason to, and I won’t pry. What’s important is, are you in a good place now? And, are you happy?”

“I am. It’s taken me a lot of effort to get there, but . . . really. I can’t complain. And, being back here again, I’m starting to realize how much I have to be thankful for.”

“Is this the first time you’ve been back?”

“Yes. Not much has changed . . . but it feels even less alive, somehow.”

“A creek may seem lively, to a fish that has never been in a river. Though in this case, I think your perception would be correct, even if you hadn’t returned with more experiences. The rural areas have been losing population, even though Bakersfield hasn’t. That always takes a toll. And it may get much worse, soon.”

“Worse?”

An aristocratic eyebrow lifted, part inquiry, part disappointment. “You have been following the news, yes?”

I must have looked puzzled; he shook his head in dismay. “How many of your classmates were born in Mexico?”

“I don’t know – maybe a third, I’d guess.”

He nodded. “That sounds about right – then and now, though we’ve gotten more from Central and South America, the last few years. For many of my students, this is the only home they’ve ever known, but they weren’t born here and they aren’t citizens. The mood in the country is turning more and more hostile to migrant workers and their families. It’s all over the news, and in the current election campaign. Think about what that means, for places like Buttonwillow, Taft, or Wasco.”

“I’m sorry,” I said, finding it hard to meet his eyes. “I was reminded, just this morning, that I’ve been focused on my own problems for too long.”

“Do not fault yourself for this! And do not imagine I am finding fault, either. You have traveled a hard road. Still . . . you need to be aware of what is happening around you, Carmen, and not simply from altruism. Migrants aren’t the only ones being targeted in this country.”

“I know there’s been a lot of attacks on the trans community.” I raised my hands, a gesture of helplessness. “Not much I can do about it. Fortunately, I live in a big city in a blue state. I got all my paperwork changed a couple years ago.”

Just then, the waiter arrived with the food. Señor Cortez had been right about the Cuban sandwich – perfectly toasted; the swiss cheese at just the right stage of melting, the ham, pork, and pickle blending beautifully. “Wow! When I think of Bakersfield – which is just as seldom as I possibly can – I think of Jack in the Box. In-’n-Out, if you’re going fancy. This is amazing!”

His teeth gleamed. “When you were a child, you thought like a child, reasoned like a child . . . and ate like a child! Places like this were here, even then. But you didn’t know to look for them.”

“I sure didn’t!”

He took another bite, savoring it properly, swallowed neatly, and washed it down with water. “People have to get away, sometimes, to find new things. Experience the richness of their own culture. But often, you can find it close to home if you look hard enough. I tried to show that to your padre, when you were a baby.”

“When I was a baby? So, you didn’t part on bad terms because you gave him a ‘B’ or something?”

“Scarcely! I started teaching in 1990. I was all of 24, if you can believe it. And your padre was my star pupil.”

He smiled, remembering. “He ruined me, you know. I thought that’s what teaching would be like – bright, driven students, eager to learn! Later, I thought, well, I’ll have at least a few every year. Now? I’m at the end of my career, or close to it. I can think of maybe ten students that really profited from what I was trying to teach them.”

I thought of the other chavos who’d taken his classes with me, including Kels and Innie and Lupe. None of them had understood why I enjoyed it so much; they’d thought it was torture. “I guess I can see that.”

“Well, by the time Juan graduated, I knew just how rare a jewel he was. I spoke with mamá Santiago, and worked with them both to make sure that he got into college. When he was accepted at U.C. Riverside and was awarded a decent scholarship, I was delighted. Even a little proud, I suppose, which was very wrong of me.”

I was trying hard not to be too bothered by the fact that I hadn’t gotten similar treatment. Wasn’t I a star pupil, too? But I didn’t want to interrupt the flow, so I kept that thought to myself.

“I bumped into him one morning when I was filling my gas tank. It must have been two or three years after graduation. April, now that I think about it, because I remember they were planting the cotton. He told me that he was back, living at mamá Santiago’s house with the mother of his child, and working in the fields.”

I thought I could see where he was going. “That must have been a disappointment for you.”

“A surprise, certainly.” He took another bite and considered his words. “More, though, I was concerned. Worried, even. He seemed like a different person altogether. Harried, frustrated, beaten down. All of that, and more. My heart ached, to see him so. I invited him to join my wife and I for dinner. At first he begged off — I think he was embarrassed. But I persisted, which was probably a mistake. They came.”

“Wait . . . you met my mother, too?”

“I did.” He sighed. “Not an easy woman to forget, your mother. Beautiful, graceful, vibrant . . . positively starved for intelligent conversation. Juan should have been able to provide it. God knows, the Juan I remembered would have been happy to. But the more she talked, the more she blossomed . . . and the more she blossomed, the less Juan spoke.”

I tried to keep my expression neutral, tamping down on the voice ringing in my head, echoing through the years. “Nothing’s wrong. Just be good to your brother, okay? Take care of him.”

He finished the last bite of his sandwich and caught the waiter’s eye.

“Sí, señor.”

“Un café cubano por favor,” he responded, then looked to me. “It’s excellent. Would you like one?”

“Yes, please.”

“Serán dos café cubanos. Gracias, señor Lopez.” he said to the waiter.

“You’re stalling,” I said with a slight smile, as the waiter departed. “I only know, because I do the same thing myself.”

“You are perceptive.” He inclined his head. “It is here that I made my mistake. I tried to help, and I had no idea what I was doing. Yolanda and I used to get together with friends to explore some of the culture in our area. Maybe go to a museum, or take a trip to the Mission at San Luis Obispo, or just hear some music. Some dinners, with good conversation. That sort of thing. We started inviting your parents to join us.”

“And that made the problem worse?”

“Yes. It became very clear, after just a few outings, that Juan could not bear to see Kathy speak with other men. He so insulted one of my friends that Trevor told me he and his fiancée would not join our group again if Juan were invited. When I spoke to Juan privately, he exploded. Accused me of pursuing his wife!”

He shook his head, still offended by the accusation after the passage of almost thirty years. “I am afraid my response was intemperate, and I assumed I would not see or hear from him again. But he showed up at my door one night, just a few months later, drunk as an Englishman, claiming Kathy was there and demanding to search the house. Yolanda was terrified and I was furious. I told him I would call the police if he ever stepped on my property again, and I slammed the door in his face.”

The waiter brought the two coffees and señor Cortez broke his story to take a sip, smile, and tell the man that it was perfect, as always. The two clearly knew each other well, though their interactions had all the formality of destreza sparring.

It gave me an opportunity to process what he had told me. At a guess, the final incident coincided with the first time my mother had left Buttonwillow — when Uncle Fernando and Uncle Augustin had gone up to the Bay Area to convince her to return.

I was lost in my thoughts, and looked up to see him watching me with sad eyes. “I am sorry. As I said, a mistake. All I had succeeded in doing was inflaming jealousies that were already consuming your father like piranha.” With a slight smile, he added, “Do drink your coffee; I should hate to bring you only grief.”

Obediently, I lifted the delicate cup and took a sip, only to find my eyes popping in surprise. “Wow . . . this is extraordinary!”

“It is, that. Anyhow . . . that’s why your padre and I did not part on good terms — and, to be honest, why I kept my distance, and never said anything to you about having known your parents. It was not a pleasant memory, and I had no wish to stir up old ghosts.”

I took another sip of coffee, and considered everything he’d told me. “I don’t remember a time my parents were together, when they weren’t fighting. It’s hard for me to imagine them being in love.”

He was quiet, sipping his coffee. Eventually it became clear that he wouldn’t respond. I wondered whether to press and had almost decided not to, when he said, “You have a question.”

“I do?”

“Avoid playing games of chance for money, young lady.” His eyes twinkled. “Yes. You have a question. So, ask it.”

“Did my parents love each other? Or was it all just some colossal mistake?”

“There is no doubt in my mind that your padre loved your mother. Maybe too much. Like Othello, he loved ‘not wisely, but too well.’ There was a song I remember, from when I was young. ‘When you’re in love with a beautiful woman . . . you watch your friends.’ I always thought it was a sad song. Tragic. He was like that.”

I set my cup down carefully. Precisely. “I notice you only answered half the question.”

He raised his own cup and sipped, his eyes never leaving mine. Finally, he said, “Correct. I don’t know the answer, honestly. But . . . Yolanda has always been wise about such things. She thought the answer was ‘no.’”

“So, you think Padre loved my mother, but she didn’t love him?”

He nodded sadly. “Yes. And it destroyed him.”

We left shortly after that, wending our way back to the hospital. As we got close, I asked how he’d learned Padre was ill.

He wagged a finger at me playfully. “You have been away too long. You know how word gets around. One of our younger teachers is the daughter of one of the men who works with your father. Et cetera, et cetera.”

“You’re right. I don’t know if you remember my cousin Inés; she described it as being like crows jabbering on a power line.”

“Exactly. A charming metaphor from – forgive me! – a fierce and fiery young woman.”

I chuckled at his dead-accurate description of Innie, then got back to the question I wanted to ask. “After all this time, and everything that happened, when you heard the news, you decided to come and read to him . . . about fascism?”

“It’s just what I happened to have with me. And I don’t suppose the subject matters. I read that some patients in comas are aware of their surroundings to at least some degree. Had I been lying in a bed for a few days, I imagine I wouldn’t be picky about the entertainment.”

“But you came. That’s the important part.”

He took my elbow again, rather gallantly steering me around a pile of dog shit I was just about to blindly step in, before replying. “I did. He was something special, Carmen, or at least, he could have been. If he had realized some of that potential, scores of people, maybe hundreds, or even thousands, might weep to hear of his condition. As it is?” He shook his head, sadly. “As it is, I may be the only one. Someone should.”

I bowed my head, abashed that his generosity of spirit was so much greater than mine, where my own father was concerned. “You shouldn’t stop teaching,” I said after we had walked a little farther. “The world needs teachers like you.”

He squeezed my captive elbow. “The world may need them,” he said lightly, “But I am not convinced that the state of California wants them. Besides, I have my avocation to fall back on!”

He let me go so I could go through the revolving doors, then followed.

“Your avocation?” I asked, as he joined me in the main lobby.

“Spanish guitar, of course. What else?”

“I didn’t know you played!”

“Teaching, the occasion did not arise. But yes, I have played for many years. I even have a regular ‘gig’ here in town.” He smiled. “You should come.”

“I’d like that,” I said . . . and was surprised to find that I meant it.

We exchanged contact information, and he told me where and when he was playing. Then he said, “I will leave you here; I know you have much to do. I can’t tell you how delighted I am, to find that you are well, and flourishing.”

“Thank you for lunch. I promise, I will absolutely come and see you play!” Greatly daring, I kissed his cheek, and watched him depart.

“My, my, my,” I murmured, as he disappeared from view. “This day’s just been full of surprises.” Certainly I would need some time to process his revelations about my parents. But the most surprising thing about our interaction was how completely and effortlessly he had accepted me. The instant his initial shock had passed, he treated me the way he would treat any other young woman – respectfully, but with a little old world gallantry that would never have come out had he been speaking with Carlos Morales. He didn’t act like I was a curiosity or a freak, much less some sort of demon. Why is it so hard for everyone else?

I returned to the ICU and asked the nurse at the desk to let Dr. Chatterji know that I would appreciate a moment of her time when she could spare it. Then I went back in and took the seat by Padre’s bed.

“Can you hear me?” It seemed unlikely. Every time I had been in to see him, he looked exactly the same. But who knows? Perhaps señor Cortez was right.

I pulled the chair closer, turning it to face him. On an impulse, I took his inert left hand in both of my own. His skin felt loose, and unnaturally cool. “Maybe this is the only kind of conversation we’ll ever have, now.”

An errant thought made me chuckle. “On the plus side, you won’t be able to interrupt me. That’ll be different.”

He slept on, impassive.

I decided I didn’t care. If he didn’t hear me, nothing lost. If he did? Maybe it would help, somehow. At very least, it might help me. “Let me tell you a story, Padre. It’s not the most pleasant story, and it might make you uncomfortable. But it’s bound to be more cheerful than Anatomy of Fascism, so there’s that.”

I squeezed his hand, hoping to feel something. The barest pressure, maybe. Anything.

But no.

“Alright,” I sighed. “Be like that, you stubborn bastard. I’ll tell you anyway. Like it or not, you’re my padre, and you should know. So here’s what happened to me, after you threw me out.”

— To be continued

For information about my other stories, please check out my author's page.

If you liked this post, you can leave a comment and/or a kudos!

Click the Thumbs Up! button below to leave the author a kudos:

And please, remember to comment, too! Thanks.

Comments

At least he won't interrupt

At least padre won't interrupt, and you never know -- there have been coma patients who woke up having heard and remembering everything said around them.

The teacher is an interesting character... almost like an emotional archaeologist in Carmen's life. It is odd, that time in one's life when a person discovers that their parents were once young and experienced all sorts of adventures and relationships.

... and to find that her father was Othello and Iago all in one! Whispering poisonous jealousies into his own ear.

So glad for another episode. Glad that Carmen has help so close at hand -- and I have the feeling that he is there to help her unwrap some of the hidden treasures of the place that she doesn't want to call home.

thanks and hugs,

- iolanthe

What a great comment!

You had me at "emotional archaeologist," naturally. I mean, that's just catnip, right? But exactly on point. I seldom had the opportunity to see my parents through the eyes of people who knew them well when they were young. I really wonder what they would have said.

Your comment about Othello and Iago had me nodding my head as well. Truth be known, I think most Othellos in this world have no need of a separate Iago. They somehow manage to be their very own snake in the garden.

Thank you for such a well-considered comment, Iolanthe. You are a joy to have as a reader, and I join RobertLouis (below) in tipping my cap!

— Emma

Careful Picking Cactus Pears

Some of the most delicious candy comes from the most prickly vegetation. Carmen is among a patch of thorns. She needs to be extra discreet what she says or does. Talking about her life telling it to her father who is in a coma might be a very bad idea. She's in a hospital and did she not hear Cortez reading to her father while she was in the hall? Young age or old age, some secrets need to be kept secret. One may be hurt personally if it is the kind of secret about one's self. Someone may be hurt if others are involved if it's something should be kept quiet. Maybe cleansing of one's soul to one's daddy while he is comatose isn't the smartest idea?

Hugs Emma, the best part of your stories is, like or hate the chapter, the skill you put the story together is beautiful.

Bab

Full moon the other night. Best shared holding the one who is holding one's heart. It's why God put it there.

Oklahoma born and raised cowgirl

Hmmm. You may have a point.

There's a risk, certainly, though I expect the fact that Carmen is trans is pretty widely known around the hospital. When she first arrived, she did have a rather loud argument with her senior aunt on the subject, which required intervention by the nurse on duty. After that, it's "crows on a powerline." Now, as we've already seen through flashbacks, there are elements of Carmen's story that go into a lot of detail that people surely don't know.

Hugs, Barb -- thanks for thinking about these real-world issues. It's the sort of thing that's easy to miss, when I'm in the middle of writing a chapter.

— Emma

A rollercoaster..

This was a rollercoaster.. I had something of an emotional day, and well this helped me. I eagery wait each upload and savor each word you share with us. Each word takes my breath away. Each word inspires me, each word helps me learn a little more about the craft. And for that I owe you a depth of gratidued that can not be repaided. I can't see what treasures you have in store for us with your next upload!

Yay!

If I was able to help in an emotional day, I'm very glad. As for repaying debts -- Rebecca, you know it doesn't work like that. And if it did, your wonderful stories more than surpass any debt there might be!

— Emma

So here’s what happened to me, after you threw me out.”

oh boy.

Well, actually, not to be TOO picky . . .

. . . but it's "oh, girl!" :)

— Emma

Like walking on ice without knowing how thick it is…….

I truly liked Señor Olivares y Cortez; a truly wonderful character, and his story added a great deal of background to the story. We learned a lot about Carmen, about her father, and even some about her mother.

But I think we, and her father, are about to learn much, much more about her life - how she survived being thrown out by her father, abandoned by her family, and having to find a way to not just survive on her own, but to become her true self. The quote from Margret Mitchell’s Gone With The Wind was very apropos:

As God is my witness, as God is my witness they’re not going to lick me. I’m going to live through this and when it’s all over, I’ll never be hungry again. No, nor any of my folk. If I have to lie, steal, cheat or kill. As God is my witness, I’ll never be hungry again.

It is easy to understand why Carmen not only remembers that quote, but why she relates to it so well.

You have built several interesting contrasts in this chapter - Carmen and her father, her father and her mother, even how Carmen perceives her former teacher - first as a child, and later as an adult, an equal if you will.

And the fact that Señor Olivares y Cortez was reading from Anatomy of Fascism was also an interesting choice. Fitting, and it brings current events into the story, as does the conversation between Carmen and her former teacher about the immigrant population. His comment to Carmen about needing to pay more attention to the current political climate is also telling - how many people who voted for Trump are even now realizing their mistake? Even now realizing how his policies will impact not just the vague “those other people”, but will hit much closer to home than they ever imagined?

And yeah…….. I remember the song by Dr. Hook very well. Even when the song first came out, the whole concept of jealousy and how it colored all of a person’s relationships was an interesting social commentary.

D. Eden

“Hier stehe ich; ich kann nicht anders. Gott helfe mir.”

Dum Vivimus, Vivamus

Some characters are just FUN to write.

And often for very different reasons. Janet, in MaxWarp, was a hoot. Kiko in Intercession. Interestingly, the "fun to write" characters often aren't the main characters in the story; they're just the folks who steal every scene they are in! Anyhow, yes . . . I fell in love with Alfonso Filipe Olivares y Cortez from the moment his name came to me. I constructed an elaborate backstory for him, I liked him so much. So, yes, I hope he can return!

And one of the things I try to do is imagine what a character like that might be thinking about. An educated, cultured, Spaniard, teaching mostly Latino kids in the Central Valley in 2024 . . . yeah, he's absolutely going to be thinking about attacks on his community, the looming threat of populist nationalism, and all of that. Knowing what it might mean to his community, and to his students, he would have to be thinking about it.

Thank you for yet another great comment!

— Emma

“He loved not wisely, but too well.”

And with that wonderfully perceptive quote, Senor Cortez gets right to the very heart of Carmen’s father’s self-destructive bitterness and failure in life. It’s quite devastating.

This is a superb chapter, Emma, a gentle, and, dare I say it, welcome, diversion from the tension and pain of the rest of the saga. Senor Cortez is yet another glorious character, almost a late coming father figure for Carmen. I really hope that we’ll see more of him, as he can provide her with both comfort and strength.

And if I may, I’d like to tip my hat to Iolanthe, because her marvellous comments mean that I don’t have to ramble on any more!

☠️

I did promise . . .

I did promise that not all of the chapters would be hard! I think viewing Cortez as a sort of father figure is entirely fair. When Carmen was his student he held back, but perhaps there might be a chance for more now. We’ll see!

Thank you for the lovely comment. :)

— Emma

Wonderful, Memorable People

In a lifetime you meet many thousands of people but only a few of them are truly memorable and had an effect on the direction of your life. I can remember only a few who have truly impacted my life. The first was the teacher who stood out from the rest and gave me my love of the English language and its literature, which has stayed with me ever since. The second was a lady who tried to show me how I could live the life that I desired, but the times were wrong and I was too scared to embrace what she put in front of me.

Then there was the boss who gave me the lessons in my career that I needed to know, not the technical basics, but how to deal with people and how to read and use contracts and to stand up for myself in a dog-eat-dog world without losing my soul.

Finally there are four girls here who make my life worth living by understanding me. They know who they are.

I have not included my family although I love them dearly. I hope that with them I am the teacher.

Emma Anne Tate shows us, through this and her other stories that there are people out there who rise above the petty squabbles and personality problems and polish the few gems amongst their pupils who have real promise. They cannot guarantee successful outcomes but they always try.

Senor Cortez must exist somewhere. I hope he is more than a character in this story.

Maybe

Maybe we all have known someone who has been like Señor Cortez in our lives. Someone who has been both inspiration and guide. I know I have, and I will confess that I love to write those characters. Fiona Campbell Savin, Nicole Fontaine, Eileen O’Donnell, Janey Townsend, Cassandra and Hermes, Sandy Wilson, Ve Volund the Skaald, Sister Sara, Sylvia Lytton, Judge Roger Danforth, Frau Talmadge . . . Goodness. The list goes on and on!

Thank you for you support and your wonderful words. Love you!

— Emma

Like it or not

She does not owe him an explanation so much as she owes herself the right to tell him. A variation on the letter never meant to be sent. She cannot, so far, know what he might hear, much less understand. Nevertheless, she needs to be heard.

Love, Andrea Lena

Exactly!

I think you have it exactly right.

Thank you, ‘Drea!

— Emma

Twists...

Yeah, the layers in this story - brilliantly crafted - have those unexpected twists and explain some key bits of Carmen's past. The encounter with her old teacher could have been a real downer, but instead pulled a few layers of onion apart so we can get a glimpse at those events that helped shaped Carmen and maybe a little about the man her father was early on. There's some heaviness, gravity in this chapter, but you handled it gracefully and I for one felt happy with how this one unfolded. I hope this story goes on for at least another 13 chapters and I believe this is the best story you've written. Sorry to lay that on ya, the pressure to stick the landing, but DAMN! so many parts of Carmen's story could be inserted going forward (chase down her mom, her past, an attraction, blah, blah, blah). Seriously - textbook masterpiece perfection I can't get enough of! Nice job Emma and thank you for sharing this with us and all your care in crafting it! Hugz Chica!

XOXOXO

Rachel M. Moore...

I can promise

I can promise that we’re a long way from the end. Beyond that generality, though . . . I can’t say. There are some things that absolutely have to happen, and they aren’t ripe yet. But I’m trying to keep the story tight, nonetheless!

Hugs, Rachel! I really appreciate all of your comments and support!

— Emma

Señor Olivares y Cortez

One of the most positive and good characters I have ever read.

Which is an achievement. It is very hard to make a very good character believable. (That is why I find Viggo Mortensen in "Lord of the Rings" Oscar-worthy.) Señor Cortez is both a crystal-clear vessel and at the same time an absolutely believable one. So much that, in fact, it makes harder to believe that he couldn't convince most, if not all children he taught to become like him... I admit I am already a fan of him. :)

And this story proves to be much more than the usual TG one. Most often, these are a road towards finding a trans person's true identity. We have this too. (I guess more will come in the next chapter, if Carmen tells there her Padre what she has been through.) But we have also something more - Carmen's road to understanding her Padre. Who he actually was, what he has been through, what he has suffered, what his words "You are no son of mine!" mean...

I start thinking that he simply must recover. Otherwise, there will be a huge missed opportunity for both Carmen and him to talk one to another, learn all about one another, understand and forgive one another.

This story has all the making of a really good one. And, whatever turn it takes, I already believe that it will be that. :)

Reaching for more . . . .

I like a good TG story. The classic voyage of self-discovery. Taking the way less traveled— the road so many of us did not take, and fantasize about. Many of my favorite BC stories fit that pattern.

But life is often so much more complicated than that. Our trans natures are incredibly important parts of our stories as individuals— but they are far from the only part. We have jobs and friends, challenges, families with their own issues . . . and we all have a past that we carry around with us. Our own, and more than our own. As Señor Cortez tells his students, quoting Faulkner, “All of us labor in webs spun long before we were born, webs of heredity and environment, of desire and consequence, of history and eternity.” I am striving to capture some sense of that in this story. When it’s all done, tell me whether I succeeded!

Obviously, I love this character, the teacher. I am delighted that you like him, too!

— Emma

The road to self-discovery...

... is not outside us, it is inside us. Fantasizing about steps that could - or couldn't - be taken in the real world is traveling that road inside us.

Well, I think so. :)

In Amarillo it would be grackles

They swarm the trees in the evenings or roost on the powerlines.

Senor Cortez is very aware of history, even if most of his students could hardly care less.

And so he is very aware of what has been happening in American politics for the last ten years.

The dark forces have been gathering and swirling around us for the last 20-40 years. And they feel their opportunity.

And after dumping millions of gallons of water that would have irrigated the fields of Kern County, Trump is rounding up or scaring off the workers who would have harvested the crops.

Gillian Cairns

Grackles are fierce!

I once saw a flight of them chase off a red-tailed hawk, definitely a major predator. But together, they were unstoppable. Lessons in that.

All I could think of, when reading your political commentary, was that line from The Battle Hymn of the Republic: “He is trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored.”

It will be a bitter harvest.

— Emma

I love this teacher...

The easy loving humanity here is just beautiful... really awesome that Carmen gets to experience that easy understanding of a human seeing another human for who she is, not who she's expected to be.

Sorry for not commenting sooner! Things have been so busy!

I like Turtles.

Yeah . . .

. . . I'm a sucker for this guy, too. "Easy loving humanity" puts it really well.

No worries about the timing, Alyssa. Just happy we haven't lost you!!!

— Emma

Spanish Guitar

Spanish guitar, eh? If Carmen keeps in touch with Señor Cortez, maybe she should take up flamenco dancing...and then need a second job just to afford all the beautiful dresses! ;)

The details to her parents' backstory have been a slow weaving into this tale, which has fostered suspicions of even more twists to come. And given the painful separation, I must wonder whether Carmen - even as Carlos - reminded her dad of her mother too much. If so, Carmen declaring as trans would for her father be bundled with all sorts of additional emotional baggage. From his (admittedly heavily warped) perspective, Carmen's not attempting to return all these years could be construed as yet another example of his being abandoned by women. The bitterness obviously runs deep in him, as shown by his overweening jealousy - a likely manifestation of insecurities from having himself abandoned a brighter future and all the talents Señor Cortez had recognized and fostered.

Intricately painted characters and story, Emma!

Through a glass, darkly . . . .

While it hadn’t been part of my original outline for this story, one thing that has emerged as it’s progressed is that we consistently get to see Juan Morales through the eyes of others. Carmen’s, then Abuela’s, then Ximo’s, Augustin’s, and now Señor Cortez’. For a character who has done nothing but lie in a hospital bed, I find him strangely fascinating. . . .

As to Flamenco. . . We’ll see! Thank you for your kind comment!

— Emma

It is a good example of how each of us sees…….

Things or people differently. Our own prejudices and preferences influence how we feel about everything and everyone. Not to mention that each of us acts differently around each person we encounter, which of course then influences how they in turn see us.

In physics, there is something known as the observer effect, which postulates the disturbance of an observed system by the act of observation. This is often the result of utilising instruments that, by necessity, alter the state of what they measure in some manner. However, if we apply this to social dynamics, the interaction between any two people by necessity has an effect on how they each act. And obviously, depending on how they feel about each other, as well as on what they are doing, or even what they have done prior to interacting with each other, there will be an obvious change to how they interact.

If I am angry or upset about something that just happened, some of that will bleed through in my interactions with others immediately after. If I am tired or don’t feel good, that will also have an impact on how I interact with others. I become irritable when I have spent too much time without sleep, and no matter how much I try not to, it can affect those around me. This can color how a person feels about me if it is the primary impression they receive.

If I dislike someone, no matter how much effort I make to not let it show, I will definitely act differently than if I truly liked spending time with them. A good case in point, several members of my spouse’s family have said particularly nasty things about me since I transitioned - not to me, but what they have said has of course gotten back to me through others. Or they have done things like excluding my spouse and I from a family wedding, while inviting everyone else; the obvious reason being my transgender status. Yet when we see each other at family get togethers they act like these things never happened, whereas I cannot pretend they didn’t and will either ignore them, staying as far away as possible - or on several occasions we have left after explaining why to the hosts. I try to be the bigger person, but I will admit that I have made my feelings about them plain to one and all.

My point here is that no two people will see another person the same way. Our opinions of that person will always be influenced by our own feelings, beliefs, and experiences with the individual. I know for a fact that many of my spouse’s other siblings (she is one of fifteen children, so it is a pretty good size sampling) agree with how these particular family members feel about me. Yet others do not agree with them. Within that same group of fifteen siblings there is a huge diversity of political opinion as well, and that obviously tempers how each of them sees others - I just happen to be the catalyst that often brings those differences to the surface.

One thing that I have found somewhat funny is that the one brother-in-law who is the biggest asshole, who is most open and blatant about how he feels about me, is perhaps the one that I grudgingly admire. At least he doesn’t pretend to like me when we see each other, being very open about his opinions. He is still a huge asshole - but at least he isn’t a hypocritical, two-faced jerk, lol.

D. Eden

“Hier stehe ich; ich kann nicht anders. Gott helfe mir.”

Dum Vivimus, Vivamus