Author:

Audience Rating:

Publication:

Genre:

Character Age:

TG Themes:

Other Keywords:

Permission:

|

A Turn of the Cards

Chapter 6. Dead

|

Then one night, as we swarmed around the tables at Caesars Palace, the wheels fell off. Dan and I were teamed up again, and we were seated at the table no more than 30 minutes before he gave me the signal to abandon ship. At first I wasn’t sure he’d actually made the signal, and I hesitated. He was getting up from the table and leaving, but the dealer had just started dealing me a new hand. I looked down at the cards, then up at the back of Dan’s head as he lumbered away from the table. Fuck, what was the count again? Plus 6.

I looked around. Lucy and Dan were gone from the table across the pit. The count wasn’t important. Time to go. Definitely time to go. I scooped my chips up, tossed a twenty-five dollar chip to the dealer, and headed for the exit as nonchalantly as I could, but before I got twenty yards from the table I was intercepted by a large – make that enormous – guy with no neck, who grabbed hold of my arm and practically spun me around to face a smaller man in a suit. The smaller guy was still at least 4 inches taller than me.

“Game’s up, Alex,” the smaller man said.

How did he know my name?

He smiled, a thin, humorless smirk, and as though he’d read my mind, said: “How do I know your name? I know everything there is to know about you.” He laughed then. “Everything about you. And the rest of your team. Please send my regards to Dan and Henry. And tell Arun hello from John Mantonelli.

“But enough pleasantries. More importantly,” he continued, “our software knows you.” He gestured to the ceiling, and I looked up to see the shiny black bubbles where the all-seeing security cameras were hidden. “Any time you step in the door, our computers are going to know, within minutes. Now, why don’t we go somewhere private to talk?”

“I don’t think so,” I said, remembering Arun’s warnings. “I was just leaving.”

“It will only take a few minutes.”

“I was just leaving.”

“Sure you were.” He seemed to weigh his options.

Blackjack isn’t poker, but sitting around a table for hours at a time, and watching people’s decisions, you get to be pretty good at working out what’s going on in their heads while they’re working out what to say. Legally he couldn’t force me into the back room, and I could see in his eyes that he knew I understood my rights. Arun had been very clear about that. He could try all sorts of pressure, but since all they ultimately had was the ability to get me on a trespass charge in the future, forcing me to stay on the premises would have been unwise.

“Look, Alex,” he eventually loomed over me. “I could make this very hard for you.”

He paused, obviously thinking, then deciding.

“But you seem like a decent girl,” he continued. I wondered if the relief was obvious on my face, but he went on. “You’re a little whacky, but decent. Probably in over your head. How about I just get you to pass on the message for me? This place is dead to you, now. Dead. You’re barred. Finished. Tell Arun it doesn’t matter what you do, you’ll never play here again. And if I have my way, the same thing will be true at every other place in Vegas.”

I didn’t head straight back to Boston. I was too unsettled, but I couldn’t stay in Vegas. Nothing could have kept me in the same town as John Mantonelli for the night.

After our debrief the others all headed off to McCarran, but I had a bad feeling about travelling as a group and I felt like I needed some breathing space, so I rented a car and drove. I had been terrified in Ceasars, and it was going to take a while for that to wear off.

I took the back roads North out of Vegas, up into Death Valley. By dawn I was standing at the Mesquite Flat Sand Dunes, watching the sun come up, feeling slightly more at ease. Death Valley is a scary place in the heat of the afternoon, but at dawn it’s remarkably peaceful, and the clear sky had more colors in it than I'd ever imagined possible. It was orange and yellow and blue and indigo, and maybe there was even some green there somewhere. It went on forever. I climbed up on the roof of my rental car and sat there for a good hour, alone, trying to empty my head of all the thoughts that had been crowding it for the previous few years.

Sitting watching the dawn reminded me of the first time I'd seen a sunrise, back when I was ten on a road trip from Lincoln to L.A. For reasons known only to my dad, he'd decided we needed to leave at 4am “to beat the traffic,“ which might have meant traffic in another city he expected to get to later, but made no sense in relation to driving out of Lincoln. Mom, as was her way, agreed stoically but insisted on wrapping Susan and me in blankets and laying us in the back of the station wagon with the seat folded down so we could sleep. I didn't sleep; I just propped myself up on some luggage and watched the world go backwards through the rear window of our Chevrolet Caprice wagon. As the sun came up behind us I was the only one to see it. That trip had been my first time to L.A., to my grandparents' Japanese-themed Pasadena home, and it had opened my eyes to a huge world with so many more possibilities than Lincoln.

That started me thinking of Sobo (Grandma) Rousselot, the smartest, most down to earth woman I knew. It had been at least two Thanksgivings since I had seen her. She had lived through a world war, emigration, having to learn English and raise two children with practically no help from my mad-scientist engineer grandpa. I admired her immensely.

At 6.30am I looked at my watch. I could easily make it to L.A. by the afternoon, even with a stopover for sleep.

Once the sun was properly up and the dawn gone, I drove over the range and across the Panamint Valley, and hit a motel in a place called Lone Pine, at the foot of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. It’s a pretty town, in the shadow of Mt Whitney in the mornings. I slept there for three or four hours and then hit the road again. Driving was good. Driving stopped me thinking. The radio played old songs that I didn't know well, and the experience felt like a 70s movie.

I arrived at Grandma Rousselot’s house in Pasadena in mid-afternoon. I wondered whether I should have called ahead. I hadn’t seen her in years, and I wasn’t sure how she’d take the changes I’d made in my life. And wasn’t it kind of rude of me to just show up, unannounced? I told myself if she wasn’t home I’d just head for the airport. To be on the safe side I had changed into jeans, sneakers and a t-shirt, which was girly but not unbearably so. I wasn’t wearing a bra, for maybe the first time in 6 months.

I rang the doorbell and waited. There was a small sign just next to the door that Grandpa Rousselot had put there years earlier, which read “This is the home of a Japanese woman. For peace and harmony, please take off your shoes before entering.” I smiled, remembering, and took my shoes off and placed them on the rack next to the door. I hoped I wasn’t being presumptuous and she’d let me in.

I needn’t have worried too much. She was delighted to see me. “Such a surprise!” She hugged me. Even though I am usually described by people as 'slight,' next to Grandma I felt like a giant. She was tiny, maybe 5 feet tall at most, and she had such clear white skin it was almost luminous. As we hugged I couldn't get over how physically frail she'd become since I'd seen her last. She felt so thin and light it was like she was made of papier-má¢ché.

Grandma shepherded me inside her immaculate home. Even though her eyesight was next-to-gone entirely, the house was still spotless.

I enquired after her health, asked her what she’d been doing. How was she coping with Grandpa gone? Did she have enough help around the house?

Of course Grandma had that wisdom with age thing that goes with having raised kids yourself, having taught high school geography for fifteen years, and having looked after a husband who was literally a rocket scientist at JPL but who couldn't find cornflakes in a supermarket. She was a smart woman, and despite her lack of eyesight there was no getting anything past her. She was onto me the moment we first hugged, but she was smart enough to let me dig a whole series of holes to fall into before confronting me with her questions.

For someone with next to no vision she knew her way around her house, and she started to make tea before I insisted on doing it. “Jouzu dayou ne,“ she said (“I'm quite capable“), but she let me take over. “Gwen comes in most days in the morning, and does my shopping for me, but otherwise I cope just fine. They wanted to put me in a home,“ she scowled. “Don’t ever let other people make those choices for you, Alex.“

Grandma had taught me the proper way to make tea when I was a child. Unlike Mom and Dad, she was a natural born teacher, and so almost everything she ever taught me stayed with me. So I made tea, as best I remembered, using an actual teapot and sen-cha, the kind of Japanese green tea that's mixed with roasted rice. Just the smell of it made me remember my childhood visits here in Pasadena, listening to all the adults talk. Proust was right.

Grandma asked after Mom and Dad, and Susan, but it seemed like she'd spoken to Mom on the phone much more recently than me, so I ended up asking her a bunch of stuff instead of the other way around. And then I told her about Tom, and about Susan and how well the two of them clicked and how pleased I was about that, so at least that was some news I had.

“And what about you, Alex?“ she said. “You certainly sound like your life has taken a different direction. You smell that way too.“ She smiled. “I think I bought that same body lotion for Susan for her birthday this year.“

“Uh, yeah. Maybe.“ It was not one of my more articulate moments.

“Susan mentioned to me that you were going through some changes in your life.“

“You spoke with Susan recently?“

“She calls me almost every week.“

“Oh. So you knew about Tom, and everything …“

“Yes, but it was so lovely to hear your perspective on it. I so seldom see you. It’s good to know what you're thinking about.“

“Well …“

“Do you remember, Alex, how alike you and Susan were when you were little? People practically couldn't tell you apart.“

So I knew, at least, that Susan had been talking to Grandma about what was going on with me.

“Uh, Grandma, um … You know, talking with Susan, do you talk to Mom about me, too?“

“What Susan tells me in confidence, stays with me, Alex. You of all people, as the descendent of a Sasaki woman, should know that.“

“Yeah. But you just told me.“

“Only the things I knew about you. Which, by the way, we haven't even begun to talk about yet. And I would never tell you what Susan thinks about you. You'll have to ask her that yourself.“

So we had a long, long conversation over tea, about what had been happening in my life. Minus the stuff about playing cards. Which meant we mostly talked about gender.

If it sounds strange that I was able to talk to a seventy year old woman about gender confusion, it shouldn't, really. Grandma Rousselot was probably the most open-minded person I knew. When my cousin Antoine was sent to a rehab clinic at age fifteen, it was Grandma that persuaded his parents to do that instead of just kicking him out of the house. She even had Antoine stay with her for five months when he was trying to get his life back together. She never tried to ingratiate herself with her grandchildren by trying to be 'hip,' or by throwing money at us. She was just solid, reliable, and not always inclined to side with our parents. I loved her to bits.

The other thing that went with not being judgmental was that — unlike my parents — Grandma almost never offered prescriptive advice. “I'm sure I wouldn't know what to do“ was a common refrain. But because she didn't have actual answers, she made a great sounding board for discussing difficult issues.

It turned out she hadn't told my parents what was going on with me. “For one thing, you hadn't told me yourself, and I wouldn't betray Susan's confidence with your mother. And for another,“ and here she smiled, a wicked little smile that hinted at the disciplinarian in her, “you are not going to get off that lightly. You are going to have to talk with your parents, and nobody else can have that conversation for you. Judging from the way your voice sounds, I would guess that you haven't spoken to them on the phone for some time. Is that right?“

“Yes.“ I had really been neglecting everyone important to me. I felt ashamed of myself for that.

Grandma probably sensed that, because she changed the subject. We talked, and talked some more, and eventually I got the impression I might have been wearing her out. She was so much more frail than I had remembered.

Just before I left, Grandma disappeared into her spare room and came back out with a cardboard box, about 18“ on all sides. “This is for you,“ she said. “I would have wrapped it, but I didn't know you were coming, and I didn't know you needed it.“

On the top of the box was some text in Japanese script which said: “nana korobi ya oki“. I'm not great at reading Kanji, but I knew enough to get that. It means “seven times down, eight times up“ – a call to never give up.

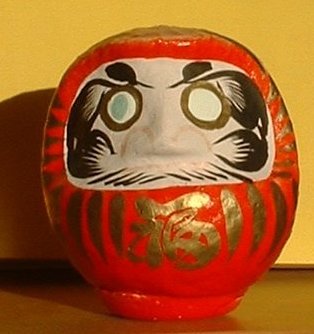

I opened the box. “It“ was a Daruma. If you've never seen one, a Daruma is a kind of Japanese icon, a head, shaped almost like a barrel or cask, mostly red with a white face, and blank spaces where the eyes should be. It comes with no eyes, and you only start using it when you add one. The idea of the Daruma is to constantly remind you that you have a task to undertake. The empty eye glares at you every day, reminding you of your failure to achieve your goal. Reproach is a very Japanese thing.

“You know how to use it, don’t you?“ Grandma asked.

“I think so,“ I said. “I fill the first eye in when I figure out what I have to do, and the second eye in when I've achieved my goal. Is that right? Ryouhou no me wo akete iru.“ (Both eyes open).

The phrase is from an old Buddhist koan, and refers to the realization of a goal. I remembered it from when Grandma had congratulated Susan at her high school graduation.

“That's it, exactly.“ She was pleased. She went to take my hand, but rather than grasp it I set the Daruma in its box on the floor, and swept her into a hug again instead.

“Hisashiburi obaa-chan,“ I said. (“I don’t see you often enough, Grandma“).

“That's true,“ she said, hugging me back tightly and obviously pleased I tried some Japanese. Although I usually thought of her as Sobo, the informal term for one’s own grandmother, I hadn't called her Obaa-chan since first grade.

“But whenever I do see you, I'm so glad. Thank you.“

“Well, thank you, for coming. You're my most interesting grandchild, Alex. And I mean interesting in the very best sense of the word. Life would hardly be worth living if it was dull.“

“I can think of a more moderate approach to take,“ I said. “But thank you. And thank you for the Daruma.“

“You realize now I've given it to you, you’ll have to bring it back here, when you've accomplished your goal?“ Grandma said. “I'm not completely altruistic. I get to see you again.“

It was true. Fulfilling the custom meant returning the Daruma to the temple it was bought from, in this case the Pasadena temple, after the goal had been attained and the second eye filled in. It was customary to burn the Daruma at the temple, buy a new Daruma, and set a new goal. But I had yet to figure out what my first goal was.

After leaving Grandma's I sat in a bar on Melrose, wondering whether or not it was too late to call Pete. Or maybe Lucy. I didn’t feel like talking to Susan or Alice. But it was getting late in Boston. The sun was only just going down in LA, and a few people had begun filing in to the bar after work. I’d gotten changed in the car and had a hint of breasts under my t-shirt now, and I had been through the customary carding ritual before I sat down. I was nursing an imported beer, looking at the Daruma which I had placed on the table in front of me. A young Asian woman had begun playing guitar in the cafe, and it was oddly soothing to listen to her mutilate Video Killed The Radio Star, slowed down, with only her acoustic guitar. When she moved on to treating Abba’s Dancing Queen like it was a torch song I was less soothed, but I guess re-interpreting pop songs in a melancholy way was her shtick and by god she was going to shtick it to Los Angeles until it noticed her.

The bar was pleasant. If I'd been in Cambridge, in Grendel's or another dive near Harvard Square, drinking on my own, I'd have been besieged by young male slackers or Harvard students. In L.A. it seemed like I was just a casually-dressed girl, in a bar, early in the evening, with a Japanese religious idol on the table in front of her. An everyday thing in L.A., no doubt.

Once alcohol becomes involved my thinking processes become less linear, and so I was alternately wondering 'how did I come to be sitting here in Los Angeles in a padded bra with an identity crisis?' and 'what kind of goal did I have to work with, to use Grandma's gift of the Daruma properly?'

Common sense finally won out over alcohol and I stopped drinking and thought about the Daruma itself. The whole idea of a Daruma was to begin a process of evaluation. It’s like the Japanese way of pre-empting the need for therapy. First, you figure out what you need to have as a goal. For most people, that's easy — everybody has wants. For others, like me, it’s harder. I really didn't know what I wanted from life. I had money. I had a few good friends. I had my health. But I had no real direction. What did I want?

Seeing Grandma had made me feel good. Seeing Susan made me feel good. Seeing Pete made me feel good. My goal would be to be true to my friends and my family, to put their interests before my own for the next year. For at least the next year. it wasn't really a goal directed at my own life, but it seemed like trying to do better by other people was more noble than focusing on myself.

I checked into a hotel in Century City and booked myself an afternoon flight home for the next day. In my beige hotel room, with its view of the building that had served as Nakitome Tower in the first Die Hard movie, I didn't sleep very well. The warning from John Mantonelli was still in my mind but over on the table in the hotel room the Daruma was colorful and meaningful. I had missed so much these past few years by not paying enough attention to my friends and family.

I got up from bed and went and sketched in an eye on the Daruma. When I got back to Boston I'd do it properly, with a sharpie or maybe a brush and ink, but for the time being I had a goal to better myself, and an icon to reproach me when I failed.

There was still an April chill when I arrived back at Logan, and I wrapped my coat around the thin red dress I’d been wearing when I left LA. I’d travelled enough to know that a dress is about the least practical thing you can wear on a transcontinental flight, but I’d put myself in first class and loaded up with blankets to compensate.

Coming in from Logan I couldn’t even be bothered arguing with the cab driver over the route.

I dragged my bag up the steps to our apartment. There was a light on in the window. I had never been so pleased at the thought of seeing Pete. I opened the door, dragged my bag inside, calling out “Pete, I’m home!”

I hung up my coat, and walked into the living room. As I did so I could see some arms waving above the top of the couch, which faced away from me, and then I saw Pete’s face, slightly flushed, rise above the back of it. And then, immediately afterward, a woman’s arm, raised up, and then her face, too. Her hair was mussed.

“Uh, hi,” Pete said nervously. “I wasn’t expecting you back until tomorrow.”

“What is this?” the woman on the couch said.

“Uh,” Pete looked embarrassed. “Debra, this is Alex, my, er, roomie.”

“Your roomie?” Debra looked unimpressed.

“Uh, yeah. You know, I live here?” I said. I don’t know what expression was on my face, but I probably looked about as unimpressed as Debra.

She had stood up, and I could see her blouse was in serious disarray. I had to hand it to Pete, he knew how to find good looking women. She had gorgeous dark hair, mussed or no, and, as Pete would have said to me two years earlier, she had a serious rack on her.

He’d stopped making those kinds of comments about women to me recently.

Debra looked at Pete. I figured he had about ten seconds to clear the air. I had no idea what he’d told her, if he’d told her anything. But a woman in an expensive silk dress intruding into what was obviously a bit of foreplay was clearly not something she’d been expecting.

For that matter, Pete making out with a woman on our couch wasn’t something I’d been expecting, either.

I didn’t know whether I should help clear the air, or burst into tears. Instead, I said, “I’m going to bed. Nice to meet you, Debra,” and went to my room. It seemed the safest thing to do.

Why was I upset at Pete being with a woman? Was I jealous? Was I going mad? All I wanted from him was some reassurance after what had happened in Vegas. I didn’t want anything else. Debra had nothing to fear from me.

And yet, I also had formed an immediate impression, without so much as exchanging three sentences with her, that she was no good for Pete.

I was jealous. What was wrong with me?

Next morning, I was up uncharacteristically early, before dawn. I’d had a rough night’s sleep again, still full of images of my encounter in Vegas. I wasn’t sure whether or not Debra was still around, so I dressed in a skirt and sweater. I nodded to the Daruma before I left my room, then made coffee, cleaned up the glasses in the living room Pete and Debra had left from the night before, and read the paper. Around 7.00am I heard Pete get up and go into the shower. I wondered if Debra was still with him. But less than ten minutes later he was downstairs, solo, clean but with stubble, wearing his standard CEO-startup outfit of blue jeans and black t-shirt with a well-cut jacket.

“Morning,” I said, neutrally. Of course I wanted to ask about Debra, and in times gone by, when Pete and I were just guys hanging out, I wouldn’t have hesitated, but now I held back. It shouldn’t have had anything to do with the fact that I’d actually worn a skirt that day, but somehow, the dynamic between us had changed. I wasn’t just Pete’s best friend any more. I was something else.

Pete, of course, acted like nothing at all had happened the night before. “Morning. You’re up early.”

“Couldn’t sleep.” I handed him a cup of coffee, which he accepted gratefully.

“It’s not like you’ve ever been a morning person.”

“I have a couple of things to do today,” I lied. I had nothing.

“Me too,” Pete said. “I’ve been meaning to tell you. We closed our mezzanine round.”

Immediately any residual grumpiness I has toward him was extinguished. “That’s fantastic news, Pete. Awesome.” Mezzanine finance was what Pete’s business needed to grow from its small startup status to exploit their patents properly. With the money they were raising, they would be able to continue development on their pattern recognition software, but they’d also be able to explore marketing it properly.

“So don’t you want to know how much?”

“I guess. You know I don’t know much about finance.”

“Ten million. It values us at forty-five.”

Forty-five million dollars. It was an insane amount of money, especially for a company with fewer than twenty employees. I knew that before the deal Pete and his two co-founders personally held at least 75% of the business. This deal had probably diluted that substantially, but even allowing for dilution, Pete was, on paper at least, a millionaire many times over.

He was grinning like I’d rarely seen him grin before. Without thinking, I wrapped him in a hug. “Congratulations!”

Reflexively, he hugged me back, both of us also trying to hold on to our coffees. The hug only lasted for a few moments, and then I pulled back, embarrassed.

“So when’s the Lamborghini arriving?” I joked, trying to brush over the awkwardness.

“It’s all going into the business,” Pete said. “Although I did think we could think about maybe buying a house instead of staying in this sweatbox another summer.”

We. He said we. Why would he want to buy a house with me? He must have meant he would buy the house. Or he meant he and Debra would buy it. If Debra was more than a one night stand. I’d hadn’t heard him talk about her before.

“So is the deal all closed?” I asked. I really didn’t want to know about him and Debra.

“Signed on Friday night. You were out west, or I would have called you.”

“I’m really pleased for you, Pete. Really pleased.”

“I’m pretty fuckin’ pleased, too.” He handed me his empty coffee cup. What was I, the maid? But it was hard to be cross with him, he was so full of energy and enthusiasm.

“Well, don’t spend all of it on the first day after the deal,” I said, and waved him from the kitchen. Pete never ate a proper breakfast, always grabbed a bagel and coffee on the way to the T. He was going to be late if I didn’t push him out the door.

Forty-five million dollars. It made my biggest nights in Vegas look insignificant.

It took a week after we had separately slunk back to Boston for Arun to finally call a team meeting. I think we were all relieved to have the breathing space. I certainly was. While I was relieved to have escaped the terrors of the back room and the kind of beating Henry had enjoyed, I wasn’t exactly thrilled at being told by John Mantonelli that my income stream had suddenly dried up.

We all met at a cafe in Alston, just after it had officially closed for the day. As usual, I was the first to arrive, and from my vantage point next to the window I watched the others park on the street and trickle in. Dan, predictably, drove an enormous Dodge pickup. I wondered how on earth he found anywhere in greater Boston to park something so huge. Arun surprised me by arriving in a new silver Acura 2 door, together with Alice. I’d have picked him for sure as the kind of guy to buy something European. I knew the Acura wasn’t hers, since she didn’t have a car.

“Fucking face-recognition software,” Arun said, when we were all finally seated. “Computers are ruining the world. All of you computer geeks, you’re killing the business.”

“What’s this 'all you computer geeks' stuff?“ Dan said.

Arun waved dismissively. “Whatever.” He looked around at the seven of us remaining in the team. Dan, Alice, Bob, Lucy, Emily, and me. Ziyen had left a few weeks ago, after deciding a few hundred thousand was all he needed to go back to China and start a new business. The rest of us had all adjusted our lives and relationships around the work. Which I should rephrase: the rest of us had essentially all abandoned our relationships, and whatever other work we had, to focus on blackjack. And now here we were, at this impromptu meeting, having been barred from Ceasar’s, and probably most of Vegas.

“There’s a way back from this, guys,” Arun said. “we just have to find ways around the software. You all know how software works, you know there are always ways around it.”

“This isn’t our software,” Lucy said.

Arun shot her a sharp look.

“Of course. But all software works on rules. We just need to change the rules. Or the parameters the rules work on.”

“You want us to hack the software?” Emily asked, incredulous.

I was surprised. In the year or two I’d worked with Emily, I’d barely heard her say a dozen sentences, even when she and Lucy and Alice and I were hanging out together. But she was clearly pissed at Arun.

“Hey,” she continued, “if we’re going to be hacking, why not just get into wholesale bank fraud. I hear SQL injection is all the rage.” She stood up and grabbed her backpack to leave. “This is ridiculous.”

“Nobody’s talking about hacking,” Arun said. “Sit down.”

Emily hesitated.

“Sit the fuck down,” Arun said. The language sounded odd coming from someone as polished and poised as Arun. “You know I’m not an idiot. I've spoken to Jeff Orgun, our lawyer. We’re not going to break the law.”

Emily looked at all of the rest of us sitting passively, then sat down again. But she muttered: “It’s not like you can even recognize a face. So what do you care?“

I'm sure everyone heard it, but Arun at least pretended not to.

“So let’s just recap.” Arun continued. “We’ve been barred.” He paused for dramatic effect, and I idly wondered whether he’d considered a career as a trial lawyer.

“We can keep playing in Connecticut, Atlantic City, the regions,” he said, “but it’s only a matter of time. I figure we have ten, twelve weeks before our photographs are in every security room in the country. We have to change up.

“Anyone feel like chancing their hand in Macau?” He looked at all of us in turn. Nobody said anything.

“I didn’t think so. Fuck a casino in Macau and you won’t be in the back room, you’ll be underwater near the Ponte de Amizade. Monte Carlo? The Amphibians will narc us out.” The Amphibians were a rival MIT team that had left Vegas a year ago to work in Europe. They were very protective of their turf, and they had some big money backing them that enabled them to pay off local law enforcement.

Arun looked around at all of us, surveying our faces.

“No, we’re going to stay local. Stay in the USA,” he said. “We’re just going to have to change up.”

“Change up,“ Bob repeated, in his best Inigo Montoya accent. “You keep using that word. I do not think it means what you think it means.“

“Funny,” Arun said, with some sarcasm. “I mean really do something different. Fool the pit bosses as well as the software. And there’s only one way to do that.”

He stopped, as though waiting for us all to figure it out.

“The hell with this, Arun,” Lucy finally said. “What? Disguises? Wigs? Dan dresses up like Dolly Parton? What the hell are you talking about?”

“Plastic surgery,” said Arun, smiling, like he’d just provided a theorem for quantum chromodynamics.

“Plastic surgery? Isn’t that a bit … extreme?” I was glad Lucy said it – it was just what I was thinking.

“We have to change up,” Arun said. “The new face-recognition software is very slick. It looks for patterns like the distance between your nose and your lips, the shape of your eyes, the relative position of your chin to your eyes – a lot of different variables.”

“So how does plastic surgery help?” This time it was Dan asking. “Can’t we just use prosthetics?”

“Maybe, but makeup is easy to spot at a table, so that's not going to fool the pit bosses, and the problem is they only allow you to add to dimensions, not reduce them. From the research I’ve done, it seems like both adding and subtracting might be necessary in some cases.”

Arun could obviously see that some of us were less than convinced. “It’s not a big deal.”

“Says you,” said Emily. I thought I knew what she was thinking: Arun couldn't remember faces at all, so the idea of changing something so deeply personal, so intrinsically linked with our sense of ourselves as individuals, probably didn't mean the same thing to him as it meant to the rest of us. I wondered, briefly, whether Arun recognized himself in the mirror each time he shaved.

“Look” Arun said. “The good thing is that varying some of these parameters by even a little bit throws the software out completely. As far as the computer is concerned, someone whose nose is an eighth of an inch closer to their top lip is a different individual. Change the chin, too, and it’s a whole new game”

“Just the nose and chin?” Alice asked.

“Well, it will probably help to vary a few things. In some cases, maybe just one, eyes maybe, in others, two or three. It’s all a matter of doing enough to futz with the algorithms the software works with. But we might still use some things like hair dye, fake facial hair, that kind of thing, even though it doesn’t fool the software. We also have to get past the pit bosses and security, so we also need to keep it subtle. As far as the software goes, we have the advantage of an expert to advise us. Wei Cheng, who developed the algorithm the software uses, is right here at MIT.”

Alice persisted. “Can we trust him?” I could understand why she would worry. She was very pretty. Who knew what moving parts of her face around would make her look like?

“He’s agreed to work for a fee, and he doesn’t need to know any of you. All he has to do is tell us the limits of the software, and then we pass those on to the plastic surgeons. Who are, of course, among the very best.”

“There’s more than one?”

“We’ll be spreading the work among several. It seems prudent from a security point of view.” Arun said.

“And how much is all this going to cost us?” Dan asked.

“Fifty Thousand all up for Wei Cheng, and between Ten to Thirty Thou to the surgeon each, depending on what’s done. I figure around One Forty all up for the team. Less than we’ve been bringing in on a single good night,” Arun said. “And the best part is, once we’ve done it, we’re good to go for several years, maybe longer if we’re careful.”

“I don’t know,” I said. “This is a big step. What are we going to say to our families?”

“The differences can be very subtle,” Arun said. “When was the last time you saw your parents, Alex?”

“Thanksgiving before last,” I admitted. Eighteen months ago. I only ever got to go home once a year at most, and I had missed the last Thanksgiving because it was a big weekend for playing. Before we started Blackjack, I couldn’t afford to travel more often. Since then, with all our time in Vegas, Chicago, Connecticut and Louisiana, I had found it hard to schedule anything more frequent. I was glad I had been to see Grandma Rousselot, but I regretted not seeing Mom and Dad. Although given the time I had spent looking like a woman, that had possibly been a good thing. But I remembered my Daruma goal. I needed to see them more often.

“I’m willing to bet,” Arun said, “and as you know I am a betting man,“ he smiled “that your parents will be noticing other things aside from plastic surgery.”

Alice laughed, I thought somewhat cruelly.

She wasn’t wrong, though. If I went home looking like I did right then, the last thing my father would be concerned about would be the shape of my nose. I could just picture him looking at me, then down to my skirt and boots, then right back up. It gave me shivers.

“What about the rest of us?” Bob said. “A lot of us do see our families regularly. My girlfriend is gonna freak the fuck out.”

“The key word here is subtle. Subtle. I bet she’ll come around,” Arun said. “Once you explain it to her.”

“That’s not a bet I can afford to lose,” Bob said. “I need some time to think on this.”

“I agree,” said Lucy. Everyone except Arun nodded.

The next day I had a scheduled weekly meeting with Dr. Kidman, early in the morning. I usually enjoyed being his first patient, because I felt he gave me more attention. On the few occasions I'd seen him before in the afternoon I had the sense that he was still thinking through some sessions from other patients earlier in the day. Not that he ever seemed distracted, exactly, but I got a better vibe from him in the morning.

We’d progressed through a lot of the basics since I first began seeing him: parents, school years, ambitions, etc. We’d even talked about playing blackjack for a living, which took me most of two sessions to explain to him. The elephant in the room, which I’d never gotten to dealing with and he’d never raised, is why I kept showing up at his office dressed like a woman.

I’d been seeing him for almost four months. I’d never said anything, and he’d never asked. When he finally got around to broaching the subject, it almost came as a relief.

“So, Alex, we’ve talked about childhood, and your relationships with women.”

“Such as they are.”

“We haven’t got around to talking about any relationships with men.”

“Relationships?”

“You’ve mentioned a few of your male friends. You talk a lot about your friend Pete. Last month you said the way your relationship with him had changed was bothering you.”

“Well, yes, obviously.”

“Why obviously?” He said gently.

“Well, because now I’m living like this, we’re not like best buds any more. Now it’s like … I don’t know.”

“Now that you’re living as a woman?”

“Yes.”

“You realize this is the first time you’ve ever admitted to me that you’re living as a woman?”

I paused, backtracked through my memory. He was right.

“I thought it was obvious.”

“Well, I never try to assume anything, Alex. That’s why I asked you to tell me everything about your life, even the parts I might already have heard about from Susan, like your parents.”

“You didn’t make any assumptions about me based on the way I was dressed?”

“Of course I did. But I tried not to form an opinion on them, until I’d heard from you. I’d like to know a lot more about why, and how, and where you think it’s leading, but we’ve been covering a lot of other ground up until now. You know, the fact that in all our time together you’ve spoken about relationships and your parents and expectations people have of you, but you’ve never, so far, talked at all about how you view yourself.”

“You never asked me.”

“No, I didn’t. Usually patients tell me about themselves. I must say the only two other patients I’ve ever had that were transgendered spent every session talking about gender issues. I never had to prompt them at all.”

I was about to interrupt him and try to protest that I didn’t think I had ‘gender issues’ but realized that it would have seemed utterly ridiculous. Quite apart from the fact that I was sitting in front of him wearing a bra, I did think that. I just didn’t like to think about it too much.

“What we’ve been doing, though,” he continued “is talking about your world, and the way it impacts you. But not the way you impact upon the world. Do you understand the distinction I’m trying to draw?”

“I’m not entirely sure. Maybe I should have read more philosophy in my freshman year.”

“I’m not offering you any kind of diagnosis, Alex. But seriously, don’t you think that you influence the world?”

I reflected on this for a few moments. “Mostly, I think it influences me.”

“Really? How did you get into Harvard?”

“I got a scholarship.”

“So you made an effort, and created an impact on the world.”

“Then I fucked – sorry, I screwed it all up.”

“In your sophomore year.”

“Yeah.”

“Was that you influencing the world, or the world influencing you?”

“Both, I think.”

“But you got through.”

“With a truckload of debt, and the help of a lot of other people.”

“You don’t really like being obligated to other people, do you?”

“What we cannot speak about we must pass over in silence.” I said.

“I’m serious, Alex,” he said. I think he was becoming frustrated with me for the first time. “It’s not a philosophical proposition.”

“I understand you’re serious. I’m not disagreeing with you. I’m just not sure where you’re going with this stuff.”

“I’m trying to get to your view of yourself.”

“It’s not very positive,” I said.

“Why do you think you have such a low opinion of yourself?”

“Why do I think it? I think it because it’s true.”

“Alex, you’re being obtuse. It’s not like you. Do you want to end the session?”

I did want to, so I said so. Then, as soon as I had left, I regretted it. What was the point of seeing a shrink if you couldn’t be open with them? What was the point if – when we finally got to the elephant in the room – I decided the elephant was too tricky to try thinking about? It was still an elephant.

And what was the point if, when Dr. Kidman observed something about me I didn’t like, I became combative and negative? Wasn’t the point to try to get past all that?

I was disappointed in myself.

I understood that somewhere out there, people were content. Somewhere out there people loved one another. They led fulfilling lives. Or they didn’t, but it didn’t matter. But somewhere out there, there were people who felt, if not happy, exactly, at least at peace with themselves.

How did other people – the people who weren’t happy – go on?

I wasn’t sure where I was going with my thoughts. I mean, I hoped for a fulfilling life. Not exactly a happy life, not a ‘successful’ life. Just a life that didn’t feel so – for want of a better word – unbalanced.

I wondered whether the reason I was so angsty was because I felt like I wasn’t in control any more. It seemed like other people were making the decisions for me. I’d gone through the year in one passive reaction after another.

I didn't think it at the time, of course, but I was so young. I can’t believe how naive and unhappy I was. When I hear people say that their youth was the best time of their lives I usually think they're crazy. I don’t know about all young people, I'm sure there are people like Barack Obama who go to Harvard and know who they are and what they want. But I didn't.

Worst crime of all, I was too self-obsessed to know what to do about it.

After my marathon session with Dr. Kidman. I wandered over to the Common. I’d arranged to see Susan for lunch at a place not far away because she had a meeting with a dealer somewhere vaguely near there.

I had forgotten how beautiful spring can be in Boston. Everyone goes slightly mad at the first sign of warmth: plants, birds, humans. Pheromones were rampant in the bar Pete and I had gone to the night before. Most of the young women there were wearing low-cut tops under their jackets, and most of the men could barely keep their eyes off all the cleavage. I had felt a little bit inadequate. I found myself wishing, as Pete checked out a woman walking past us at the bar, that I had something to distract him with too. After we went back to the apartment I realized how bizarre it was that I’d started to think about having real breasts.

But was it more bizarre to want to have breasts, or to want to have Pete notice them?

I spent some time on the Web using Altavista when we got back from the bar, looking at the effects of female hormones on biological males. Frankly, a lot of the information I found seemed like it had been put together by fetishists or crackpots, but there were a couple of sites, both foreign, that contained some reasonable information. Basically, I could take female hormones and develop breasts and other curves, but if I did that my status as a fertile male had a lifespan of about six months. After that, no more sperm, even if I stopped taking the hormones. Apart from fertility, though, it seemed like most of the effects of hormones would be reversible up to about 12 months. After that there would be some permanent changes requiring surgery to reverse.

The problem was, it seemed like six to twelve months was the minimum I’d need to take hormones to get any kind of reasonable results. The sites that sounded most credible said that most hormone therapy took between 2 to 3 years to be fully effective, and I would become infertile in 6 months to a year. So if I started down the hormone path, and wanted to do it properly, I was pretty much committing myself to never being properly male again. I knew the guy thing wasn't working for me anymore, but wasn’t sure yet whether I could take that step.

All the same, there was a part of me that wanted to do something. I was living as a woman full time now. Everyone I knew was reacting to me as a woman. But now, as summer was approaching, I was going to have to be very, very careful about how I dressed to keep up the charade.

I hated fucking charades. I felt like a phony. Walking on the Common that morning, I felt like a fraud, and I felt envious of every woman I saw, whether she was exposing any flesh or not. How come they got to just be? How come they didn’t have to work at it? How come they could distract Pete just by wearing something that showed some cleavage? It didn’t seem fair.

They had the curves, they didn’t have to fake anything.

It was a nice morning, still a little chilly, but with streams of sunshine through the trees, a grandpa and two kids playing with a model boat on Frog Pond, and people out sitting on the Common, taking in the rays. There were two lesbians sitting on the grass. One was unmistakably the butch, hunched in a heavy leather jacket, but her hispanic girlfriend, wrapped in her arm, was wearing this very pretty cropped blue floral top under her denim jacket, showing off the curves of her belly and the tops of her breasts. I wished I could wear something like that. Or even, you know, be like the other woman on the pathway ahead of me, who was wearing a simple blouse and sleeveless top. Her ass filled her jeans perfectly. I was sure mine didn’t look like that.

A big part of me wanted it to.

Yet at the same time, the idea of doing anything permanent to my body to make myself irrevocably feminine scared me.

I didn’t think I was ready for that.

Susan and I had lunch at a little cafe not far from the Common that had focaccia and decent coffee. She looked beautiful as ever in a geometric print dress that made her look professional and sexy at the same time.

We talked about her work. She was loving work, it offered her tremendous opportunities and she was becoming quite the expert on repairing restorations that had been botched earlier in the century, of which there were apparently thousands. Then we began talking about my visits to Dr. Kidman, and I reassured her that he’d never said a word to me about anything she’d ever discussed with him. Which was, I ventured, just as well, because I’d told him some pretty screwed up stuff too, and I’d have hated it if any of that had ever got back to her.

That immediately made her insanely curious, of course. What mad secrets could I have confided to him? She just had to know. It was going to drive her crazy.

Eventually I laughed, and she realized she’d been set up, and she laughed along.

The final thing we discussed over lunch was Pete. At first I was reluctant, because talking about Pete that way made me feel like I was gay. Or maybe I was afraid Susan would think I was gay. Which I obviously was. Or bisexual. Or something. I mean, I still thought Alice was gorgeous, but recently I’d stopped wanting to sleep with her. I wasn’t even sure what I would do if I could sleep with her. With Pete it was different. I’d never been sexually attracted to him, until recently. Until I’d begun to socialize as a woman. So now I was fancying men, or at least one man, and that made me gay, right?

Except that wasn’t the point. I didn't have any problem with anyone being gay. I knew scores of gay people, and they were sure as hell happier than I was.

The point was how should I handle the way things were between Pete and me now? Should I just try the ‘strictly roommates’ thing we’d had going on so long together, which was not really working now? Or should I try for more? Did I want to try for more? I opined that I didn’t. I didn’t really want to sleep with Pete, I told Susan. I just wanted his attention. Except I wanted it in a different way than I used to.

“What you have, Alex, is a crush.”

“What? It’s serious.”

“Every crush is serious. But there’s a difference between having a crush and wanting to jump someone’s bones. From what you’re telling me, you’re deep in crush territory, but you’re no way ready to sleep with him.”

“God no!”

“Glad we got that settled,” she smiled.

If you liked this post, you can leave a comment and/or a kudos!

Click the Thumbs Up! button below to leave the author a kudos:

And please, remember to comment, too! Thanks.

Comments

Prosopagnosia

Is quite common. Next time you're on a crowded bus or subway, reflect that one of the people in the bus or carriage is likely to have it. If you're on an airplane, there will be more. I used to joke that I had it, because I'm crap at remembering people, but I think my disorder is more likely to be misanthropy.

Prosopagnosia at Wikipedia

not as think as i smart i am

The same as every time

You did a wonderful job once again.Thank you and keep it up.I can't wait for more!:)

SHEVA

as always, more, please!

I am really getting into this story, Rebecca. You're very talented and I am enjoying this a lot! Can't wait for the next chapter!

Well Arun is showing his true colors

Personally I think he is some kind of sociopath.

He certainly is not considerate of his 'friends'. So what next, have limbs cut off. This is getting way out of hand and if Alex is smart will get out of it now.

Kim

Sociopath.

I have to agree, I don't like him at all. I can foresee someone getting seriously injured or worse. You have to know when to fold them, surgery no thanks.

-Elsbeth

Is fearr Gaeilge briste, ná Béarla clíste.

Broken Irish is better than clever English.

How does John Mantonelli know Arun, &

does he have the clout to keep tabs on the group

May Your Light Forever Shine