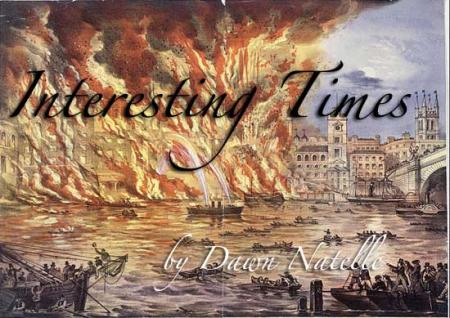

May You Live in Interesting Times

Chapter 1

Professor Eleanor Frances Halpenny was nick-named “the Hobbit” by her undergraduate history students. She was named professor emerita 1 at the university when she had passed the age of 80. She had been barely 5 feet tall when she was a young woman: now she was several inches shorter. She was extremely wrinkled. Being 84 does that to one. Her gnome-like appearance was enhanced by a shrill, high-pitched voice.

Douglas Rayles, 28, didn’t mind the old lady. In fact, he nearly idolized her. Nearly 10 years ago he had been majoring in Sociology when he took a first-year history course in his freshman year on campus to meet a degree requirement. The Hobbit was the teacher. At the end of that year he transferred to a history major, and would take five other courses with Professor Halpenny over the next three years. That first course had been listed in the syllabus as covering the history of Stuart England from the death of Queen Elizabeth the First to the beginning of the Hanoverians. In fact the course was a concise history of what the professor called the Glorious Generation. The period from 1642 to 1692 was fifty years, or the lifetime for some people of the time, that included:

- The English Civil Wars

- The beheading of a reigning monarch (Charles I)

- The Commonwealth and Oliver Cromwell

- The Restoration of Charles II

- The Great Plague

- The Great Fire of London

- The abdication/usurpation of the King (James II)

- The Glorious Revolution that brought William III to the throne

Professor Halpenny’s motto for the course was “May you live in interesting times.” Doug was enthralled listening to his professor make those years come alive through her lectures. Most of the other students did not share his enjoyment of the class. Only three or four students were there by choice. The others were merely aiming to get an easy credit in History to meet requirements for their major. In fact, Douglas started out in that group, but fell in love with his wizened old professor and what other students felt was a droning voice, he heard as a song, calling forth the days of yore.

After finishing his undergrad degree in History, Doug went on to take his Masters in the field, and was still in school, working on his Ph.D. in history. He now taught first year students in that same History of Stuart England, trying to make the course as exciting for his students as it had been for him. Professor Halpenny was now his faculty advisor, as she had been in his Masters: one of her few duties as emerita.

But today the two History scholars were in the Physics building, watching a larger crowd from the Religion department. It was recovery date on the second human test of what the Physics department called the Hawking Quantum Chronology Device (HQCD). Basically, it is the first working prototype of the time machine theorized by Steven Hawking. The initial test of the device had been allocated to the Religion department, thanks to a large donation from an alumnus. Five professors had been sent back to spend 24 hours to witness the execution of Christ. Unfortunately, that experiment was a disaster. First, the group arrived five years after the execution, and managed to learn that it had not been Eastertime, but in the fall when Jesus had been executed.

More importantly, every one of the men teleported had changed sex and to a younger age when they landed, and at that time women were not considered important enough to travel alone. Only one of the new women spoke Aramaic, making communication difficult for the English-speakers in the group. They had learned little more than the proper date of the execution before they were pulled back, where they were males again.

The History department was supposed to have the second test, but the Religion department claimed that since their test was a failure, they should be able to go again. This time there were seven sent across, including three female nuns. All seven had studied and learned Palestinian Aramaic, as well as preparing themselves much better about the geography of the area. Four of the original five professors went back: the fifth was so traumatized by his 24 hours as a woman that he refused a second trip, especially since this time a two week visit before and after the crucifixion was planned.

While the Religion people were preparing for their mulligan, History spent several weeks choosing their experiment. Professor Halpenny, although emerita, still carried considerable weight in the department, and her plan to return to 1642 was approved. She asked Douglas to accompany her. It was not an easy decision for the young man to make. For one thing, he would spend 50 years as a woman. But it would be 50 years in the middle of the 17th century, the time period he was studying for his doctoral thesis. Physically he knew he would change as well. He was now 6’4” and he knew he would not a woman of that size. The men from the first Religion experiment said that they had all become young woman of varying heights, but each was much shorter.

Finally, he agreed, and both he and the professor suspended their other tasks at the university. Learning a new language was not necessary: Shakespeare’s plays had been written less than 50 years prior to their arrival time and could still be read today. But they spend a lot of time with a linguistics professor specializing in that period who tutored them on common words and phrases, and differences in pronunciation. He claimed that the spoken word had changed much more over the past 400 years than the written word.

They also spent time studying English money, and getting familiar with the system of pounds, shillings, and pence that was used at the time and approximate values of items. Douglas spent hours learning how to do double entry accounting in the archaic monetary system. There were also penmanship classes, using inkwells and quill pens, and learning to slowly write in the fine penmanship of that era. Douglas, in particular, had to learn to write with a feminine hand. He also was required to take lessons in needlework, weaving, sewing, and other tasks expected of a female lady of the 17th century. He also learned music, and how to sing and play the piano. Finally, Douglas was taught painting by the art department, so that he would have at least the rudiments of art. Professor Halpenny had learned Latin in high school, so she merely had to brush up on it, but had to learn Greek to attain the level an educated man of the 1640s. She also learned to handle a sword, although at her age it was more theory than practice. Luckily she had learned to ride as a young girl, and knew that she would be able to pick it up when she became young again. Douglas did spend some time on horseback learning to ride. Both of them had to learn or brush up on their French, again with a 1640s dialect.

The plan was that they would arrive in late 1642 in southern England near a stage coach route that could take them to London. Professor Halpenny would become William Currie, Earl of Stanstead, and Douglas would become his sister Abigail. They would have documents that attested to their title, and most importantly, money. There were undergraduates in the History department who had been hired to duplicate early Stuart coins, and the time travellers would arrive with a satchel of 5000 pounds sterling in gold. The coinage would technically be counterfeit, but since real gold was used, this was not expected to be a problem.

The satchel was special: something that the Physics department had developed while the Religion mulligan was in progress. It was a type of portal between the time periods. Something placed in the satchel in 1642 could be retrieved seconds later in the 21st century. This would allow the university to continually refurbish the time traveller’s funds, as well as sending messages either direction.

Douglas suddenly sat up. A commotion alerted him that something was happening. He shook the professor’s knee: she had fallen asleep. The recovery of the seven from the time of Christ was taking place, only two hours late.

The people came out of the device in a row, wearing the same clothes they had entered in two weeks before. The nuns were crying softly, the male professors were either sad or angry. The Physics professor who built the device was alarmed immediately and asked what had happened.

The men acted meek, and one of the nuns became the spokesperson. “Everything was wrong,” she said. “The cross was wrong: an X instead of a T. And there were nine executed that day, not three.”

“We waited outside the burial chamber the night he was to rise, and discovered that four of the disciples came in and stole the body,” another nun said. “We followed them, and they buried the body in a different location. He did not rise as we had believed.”

“We trailed most of the other disciples, and found that they met each night that week, but none of them met with the risen Jesus. They just plotted on what to do now that their leader was gone,” the first nun said.

“It means that it was all a lie,” the third nun sobbed. “He was not a savior, just a common rabble-rouser who was killed and then carted away by his disciples, leaving an empty burial chamber. We even looked inside to see if there was a Shroud of Turin, but the room was empty. He was buried in the shroud.”

“It still could be true,” one of the angry professors said. “His soul could have risen. Some of the gospel is misleading … but it could be an allegory, I don’t feel that all is lost.”

It was clear that not all the group agreed. There was a full eight hours of debriefing, and this was the part that Professor Halpenny and Douglas were most interested in. They learned that the transfer had again switched the sex of the people. This time there was a routine that decided the ages and appearance of the transferees, which meant that two of the nuns became men in their 20s, and one of the professors became an older woman in her 30s, thus carrying a little more respect than the young girls that the others became under the defaults. It seemed the machine would make transferees the age of young adults at the end of puberty, unless otherwise conditioned. One of the professors had become a girl of 10, acting as daughter of the older woman, as an experiment. He did not enjoy his two weeks as a child again.

There was not much additional information gained by the history professors, so they left and returned to making plans over the next month while the machine was prepared for their trip. The Religion department tried to get a second mulligan: claiming that they needed to investigate further into the activities after the crucifixion, and before, when they wanted to investigate the miracles that the Gospels claimed Jesus had done. This time they were denied, and the History experiment would be next. The Music department had also put forth a project that would have four male professors go back to 1960 and spend 10 years watching the development of rock music, from the Beatles in the Cavern Club in Liverpool, then to Germany, and finally spending the latter half of the 60s in San Francisco, with a side trip to Woodstock. The Biology department also had a plan to send two female members as sailors on the voyages of the Beagle with Charles Darwin. The additional Religion projects were slotted in after them.

A month later Douglas carried a large trunk, with the satchel sitting on top of it, into the device, and then helped the elderly professor in with him. The door was sealed, and then there were swirling colors. These lasted 20 seconds, much less than the Religion group had experienced. But that group had gone back 2000 years, and this trip was under 400 years.

Suddenly the colors faded and the two found themselves on a dirt road that ran straight as an arrow. They had nailed the landing, coming in about 20 yards from a small wooden bridge that crossed the East Stour River on an old Roman road. Douglas reached down to pull the trunk off to the side of the road, and was amazed by several things.

First, he couldn’t budge the heavy trunk, which seemed to be 150% larger. Then he realized as he leaned forwards there was something surprising on his chest. “I better get that, Abigail,” Professor Halpenny … no, Earl William Currie of Stanstead said. The former diminutive professor was now over a foot taller than Abigail, and well muscled. She lifted the trunk easily. It was all Abigail could do to carry the satchel, full of heavy gold.

“We got the location right,” William said, “and judging from that dust trail down the road, I think we got the time perfect as well. Here comes our ride.”

Stagecoaches were a recent development, having been started 30 years before, but now provided a network across England. The stage pulled up, and the driver and guard seemed tense, looking around. There were no trees within 100 yards, so finally the guard hopped down.

“We have a full coach, milord and milady,” the guard said. “We will move a few to the roof seats to make room for you inside. Rich will shift your trunk up top.” The guard stuck his head in the coach and ordered two men to move out to the roof seats ‘to make room for your betters.’ Then he hefted the trunk onto the baggage area, and helped Abigail, and then William into the coach, where they took seats. The other four inside passengers were two couples, one apparently a merchant and wife, and the other a well-dressed couple who spent the next few minutes comparing the quality of their clothes with the newcomers, to determine who might have the higher social standing.

Eventually it turned out that they were a Baron and his Lady, and when they discovered that William was an Earl, they bowed politely. They initially referred to Abigail as Countess2, until it was explained that the two were brother and sister, and not a married couple.

A half hour later the stage stopped in a wooded copse. There was a tree in the roadway, and seconds later a band of five men and a boy surrounded the rear of the stage, preventing it from reversing direction.

“Out. Out everyone,” the leader of the band shouted.

This was bad. Once the bandits discovered what was in the satchel, they would take it. The gold was not important: the important thing was the satchel itself: the pair’s link with the future. Abigail thought quickly, and handed the satchel to William. She backed out of the coach, but as she did so she retrieved her secret weapon: a seven-inch dagger that she had the costume designer sew into a sheath nestled between her breasts. She may have to be a girl for the next 50 years, but she had vowed she would not be a defenseless one. William saw her draw the weapon, and smiled as she concealed it in the fringe of her blouse sleeve.

William had his sword of course, but the surprise of the dagger could be just what he needed. Before he left the stage he unclasped the top of the satchel. When he got out he dropped the satchel, and the top flew open, with a few gold coins popping out.

This caused the head bandit to drop from his horse, drawn by the massive amount of gold. He kneeled and ran his fingers through the money: “Lookee here boys. We have treasure here.”

That was when Abigail stepped forward, drawing her dagger. The man didn’t even look up until the dagger was at his throat and slicing into it. The bandit fell, and William drew his sword before either of the others could react.

One man on horseback held a primitive pistol and was about to aim it at William, so Abigail threw her dagger, aiming for his arm but hitting his chest. The man fell from his horse, and the gun bounded away. William took on the other two men in a sword fight, and Abigail grabbed onto the boy, who seemed to be about eight years old.

Rich, the guard got into the action a few seconds later, and with two swords against two, the bandits quickly were vanquished. The guard killed his, and when the man facing William threw down his sword to surrender, the guard also killed that man. He would have killed the boy as well, but Abigail stepped in front of the lad.

They surveyed the carnage. The guard had killed two. One had ridden away at the start of the fight, when he saw the lifeless leader with a bloody smile across his throat. The gunman was dead too: Abigail’s dagger had gone into his heart as well as nicking his arm. The boy was shivering in Abigail’s arms.

William gathered up his coins, giving one to the guard for his assistance. The dead men were trussed to the horses they had ridden in on. The guard collected the dropped firearm, and seemed pleased that he would have it for future battles.

“We are only five minutes to the next stage station. Then it will be another hour into London,” James, the driver said. “We will get rid of that baggage at the next station. Your lady killed two, so she gets two of the horses. The best two, I think. Rich here killed the other two, so he gets the last two. Shame we lost the fifth, but after seeing four of his mates mowed down, that fellow might be looking for another line of work. Now what are we to do with that half-sized bandit?”

“He will go with us,” Abigail announced. “He is small. He can lay on the floor of the coach.”

No one was going to argue with the young girl who had just casually killed two men, and was wiping the blood from her dagger onto the hat the bandit leader had been wearing. “Anyone want this?” she asked, waving the hat. “It’s a bit dirty now.”

“I’ll take it,” one of the topside riders said, and she flung it up to the top of the coach. The bandits hadn’t even gotten them down from their seats.

The dead men’s horses, with their noxious burden, were hitched to the rear of the stage, and the party was soon underway, although at a walking pace, which meant the normal 10 minute ride to the next stage station would take about a half hour. Inside the once-quiet riders seemed to have bonded over their experience, and were quite chatty with each other. The men now sat on one side of the coach, facing the rear, and the women were facing the front. The boy, bound hand and foot, lay on the floor of the coach.

“I’m so glad we picked you up,” the merchant said to William. “I don’t have nearly as much money as you do,” he gestured at the satchel, “but what I have in my money belt is nearly all I have. We are headed to the cattle market to buy stock for my shop in Maidstone. If I was robbed I would have been unable to buy anything, and soon my store would be empty.”

“This is very important to me too,” William patted the satchel. “We are returning from France, and I hope to be able to buy us a home in London. I am an Earl, but currently have no estates.”

“Ah,” Baron Stephen of Downsland said, “estates can be more trouble than they are worth. First we have the King’s men coming to collect taxes, and then the Parliament men come around, and want the same taxes. More and more each time, and often several times in the year. Much of our savings are gone, and we have to squeeze the people. And they don’t have money either. I wish they would realize that these wars they keep fighting cost money, and we have no more money to give.”

“You come to London too, then?” William asked.

“Yes. My lands are right at the edge of the territories, with Parliament holding lands to the east, and the King the lands to the west. I honor the King, but staying up there left me exposed to both. Here at least there will be only one set of taxes to pay, if my steward can send me money before the Stuarts get to it.”

The three men smiled at the baron’s quip. “The one good thing is that the troubles have made rents in London much cheaper. I rented a house for a third the price of last year. Usually we only come down for the season, but this year I think we will stay until the troubles are over. You should be able to buy cheaply as well.”

“The season?” William queried.

“The fall season,” the baron replied. “We have many friends in the city and during the season we all have fetes and feasts. Of course as an Earl you will be travelling in a much higher circle. But Mary and I would be quite honored to have you and the Countess, I mean your sister, attend the affair we will be hosting.”

“We would hope to come,” William said.

“That would be so gracious of you, milord,” the baron said. “For one thing, no one will believe my tale of what just happened today without collaboration.”

“Tell me more of the troubles,” William said. After all, one of the goals of the project was to find out what people thought about things. When written down, accounts often lost this human element of the story. Here he had a chance to get the impressions from two men at different social positions. They chatted all the way to the stage station, and then again all the way into London.

Meanwhile Abigail had chatted with the women. She hadn’t flowed into conversation ad quickly as her ‘brother’, primarily because the others were in complete awe of her. She had killed two bandits alone.

“You are too brave,” the merchant’s wife finally said. “To think to draw your dagger, and then to use it so quickly. Have you ever done that before?”

“No,” Abigail said. “I had practiced throwing it, but never had used one on a living person. It surprised me how easily it went into the man’s throat. The throw was not meant to kill, but the man was turning to fire his pistol at us, and it only nicked his arm. Unfortunately his chest was where it ended up.”

“You are still so calm,” the Baroness Norah said. “I am still shaking, and did nothing more than stand there and wonder if all my jewels were to be taken. And possibly more. It is said that these bandits sometimes made free with women after killing their men.”

“Oh God, no,” the merchant wife gasped. “I never thought of that. Oh my. I could never … Oh my.” Abigail looked at the woman, who apparently thought rape was the worse part of the scenario, ignoring the fact that her husband would have been killed first. “We owe more to you than we thought,” she finally said to Abigail when she was coherent again.

“Eventually the women put their ordeal behind them and spoke of other things. The women were most interested in knowing what the Paris fashions were like, and wondered what they might import for their gowns for the ‘season,’ which was a big thing for the baroness. The other woman said that the ‘season’ in Maidstone was much less ornate, although her husband’s business would double, which was why he was coming to London to buy cattle. They would not initially enter the city, but stop a stage or two outside where the cattle markets were. After they bought their stock, they would hire drovers to take it to Maidstone, and the couple would continue into the city to buy goods from London merchants, and take them home by coach, arriving a day or two before their cattle would arrive.

At the stage station, the stationmaster was out immediately to accuse the driver of being late. Then when he saw the extra horses and their cargo he stopped. Then there was a recounting of the event.

During the hour that they were delayed at the station, one coach went in the other direction and shortly thereafter another coach came on the London-bound run. It was not full, so the merchant and his wife moved to it while the baron and baroness decided to dine in the station with Abigail while William spoke with the stationmaster. Two of the outside passengers also moved to the other coach.

William came in and tossed fourteen pounds on the table in front of his sister. “I sold your horses to the stationmaster. No sense taking them all the way into the city. They wouldn’t be able to stay hitched to our coach: it would slow it down too much. If we need horses in London we can buy there. Abigail gathered up the coin. Why had William not just put it into the satchel? Then it hit her. He wanted the money split up, so if they lost the satchel they would have something.

William got the kitchen to make him a roll containing a thick slice of cheddar and as much beef. So much for the myth of the Earl of Sandwich inventing this in the 1700s. Perhaps when they returned to the present, people would be referring to it as a Stanstead.

Without the merchants the boy had a seat, although his hands and feet were still bound. He sat next to Abigail, who had gotten him a “Stanstead” and was tearing off bite-size morsels to feed him as they rode towards the big city, to the amusement of the baroness. The boy was ravenous, and ate the entire sandwich in only a few minutes, drinking from a water flask Abigail carried. He then curled up beside his benefactor and fell asleep.

“What will you do with him?” the baroness asked. “He could hang as a member of the gang.”

“He is not a criminal: only a boy,” Abigail retorted. “We will find him a place in our staff, if he wishes it.”

“He certainly will wish it, if you keep feeding him so well,” the baroness said. “That food was more than most of my husband’s tenants get in two days.”

“It was probably more than two days since he last ate,” Abigail said. “Those men didn’t seem well fed. I suspect the boy got the slim pickings that were left after they ate.”

“The women chatted alone for the next few hours as dusk fell and they approached London. The boy woke up, and found that he was no longer bound. “Me hands are free,” he said in awe.

“And your feet,” Abigail said softly. “Being bound was making it hard for you to sleep well. I trust you not to run away. You could if you wish. I will not keep you as a slave, but a servant. Will you serve me?”

The boy slid to the floor of the coach and grasped the lowest hem on Abigail’s dress. “Milady, I’ll serve you all the rest of my life. You saved me. Those men did … they did ‘orrible things to me at nights. I were glad to see you and the guard kill ‘em.”

“Rise up young man. Have you a name?”

“I is Joe,” the boy said, standing. “Hank, the one you slit his throat, says I must have another name, but I dunno what it is.”

“I will give you my name as a surname,” Abigail said. “I am named Abigail Currie. Your new name will be Joseph Curryman.”

“That’s a lot, milady, for one as small as I is. Per’aps I could stay as just Joe till I gets that big one into my head.” He did seem to show pride on his face that he now had as many names as most common people.

“Milady,” he confessed. “I kin tell you where Hank and the others stashed their takin’s.”

“What of the one who ran away?” Abigail said. “Surely he will go and move the stolen goods.”

“’e don’t know, does ‘e?” Joe said. “’e was just picked up by the boys earlier that day, new to the gang, yer see. ‘e never did a night with us in the cave. But I knows where it is. Leastwise, if you kin get me back to that there place. I’ll lead you and your brother to the booty. There is a lot. Not much money but lots of jewels and stuff. Hank takes that to the city during fair week, where there’s pawners from away what’ll buy suspicious jewels cheap.”

William had been listening to the dialog between his sister and her new servant. “We will go for a ride in a day or two, youngster,” he said. “You do ride?” The boy nodded. “How many men will we need to carry away the booty, as you call it?”

The boy looked confused, and then started calculating. “I don’t knows no numbers, milord. But there would be this many bags the size of that ‘un.” He pointed to the satchel and then started rising fingers as he visualized the booty hoard. He stopped with seven fingers up. “That many ‘ll do it, I reckons.”

Chapter Two

The stage arrived in London late, and the final stop was at an inn the baroness said was not suitable for people of their place in society. So as soon as the coach stopped, Abigail sent Joe out to find another place Norah recommended, and reserve a room for them. The baron and wife took a cabriolet3 to their rented home after making sure that William had the address for a future meeting.

Abigail’s trunk was a problem. It was too large to fit in a cabriolet, so William arranged to store it at the stage yard after Abigail got a nightdress out and placed it in her handbag. He also arranged for a driver and a local carriage for the following morning. James, the coach driver, agreed to take the commission, and promised to wait at their inn at 6 a.m.

The cab got them to the inn in good time, and Joe was waiting out front. “They’s got a room as is fit for an Earl, they says,” he reported, “and one more for milady. I hope that’s okay.”

“I’m sure it will be,” Abigail said. “I’m guessing you are hungry again. Do you think we should eat? It will be an early morning for us.”

“I could eat,” the boy said with a huge grin. “I can’t reckon ever saying no to a good nosh. Or even one not so good as that you offer.”

Abigail giggled, and then stopped as she realized that she had giggled. She led the boy into the inn, and realized that he was closer to her height than she was to William’s. The inn had no common bar, so the main room was nearly empty. The kitchen was closed, so William merely asked for buns with cheddar and roast beef slices. He also asked for more of the same in the morning, when they would be leaving quite early. The innkeeper looked askance at that, but smiled again when William said he would pay in advance. Abigail didn’t see what the charges were, but William paid with shillings and not pounds. She would have been happy paying pennies at the ‘low class’ coaching inn but realized that people of her status must keep up appearances.

In her room, Abigail struggled to get out of her dress, which was somewhat soiled. She would have to wear it again in the morning. She learned why women of these times had maids … she was completely stymied in getting the garment off.

There was a tap on the door while she was struggling, and William slipped in. He saw the problems that she was having, and moved quickly to help. “But you are a man now,” Abigail hissed as he unbuttoned the back of the gown.

“You have nothing I haven’t seen in a mirror every morning for over 70 years,” he said. “Although not as much, I’ll warrant.” He added as he lifted the gown from her and laid it on the bed, revealing her in her undergarments.

“I thought as much,” Abigail said as she looked down on her breasts laying atop her corset. “Those clowns in the Physics department changed my pattern. I was supposed to be a C cup. I’m only 15 here, dammit. “But these are at least DDs.”

“I’ll say,” William said, staring at her barely covered breasts.

“And if you will just loosen the ties on my corset, then get the hell back to your own room. Or the washroom. The parts that you haven’t had for over 70 years are starting to alarm me.”

William looked down at his first ever erection, and did as Abigail said. He hurried from the room, muttering ‘my sister. She’s my sister’ as he did. With the big man gone, Abigail pulled off the corset and put on the nightdress. Why was she panting heavily, she wondered. Was it from being undressed by a tall, strong man? One that was able to tent his trousers in such an interesting way?

The next morning the boots4 rapped on the door at 5:30 to wake them, and William came in her room a few minutes later. Abigail had just managed to get back from the washroom where she did her morning ablutions. William helped her into her corset, and then the gown from yesterday.

They went down to the dining room, where the cook had the requested rolls ready. Joe darted out the door and then popped back in, announcing “Coach’s here. Same driver as yesterday,” he said. “Looks like yer trunk is on top.”

They ate their breakfast in the carriage. Joe reveled in having his third meal in 24-hours, more food than he usually got in a week. He had prayed for the first time in years last night, thanking the Lord for having milady find him, and take him in. He also prayed his new lord and lady.

James, the driver, recognized Abigail’s description of the place she wanted to go. In her research back at the university Douglas had learned of a certain Duke who had become insolvent at the time they were now in. His butler, who had served the Duke’s father for 25 years, and the new duke for nearly 15, had committed suicide the very morning they were now in.

There was a B plan if they didn’t meet the butler, but things would work out much better if they found him before he jumped. Even more so for the man. James stopped at the spot Abigail indicated, and the three of them got out. Joe ran ahead with specific instructions to delay the man, if he could be found, while the time travellers walked along the river, looking down below to see if there might be a body in the weeds. James stayed in the carriage, and moved it along every few hundred yards that the couple walked.

It was a foggy morning, and it was hard to see down to the river’s edge, but Abigail peered hard to see if she could spot anything. Eventually William nudged her, and she could see Joe up ahead, talking to a man of about 50.

“Good day sir,” William said. Abigail noticed that the man was sweating profusely in spite of the cool damp, and seemed to be nervous, although Joe was chatting animatedly with him. The man’s clothing was that of a high-class servant, but worn and tattered looking.

“The river is interesting in the morning,” William said. “It is our first day in London, after spending some time in France, and before that in India, where our parents made their fortune, but lost their lives to the disease. We returned, travelling through France, with several months in Paris. Now we are here to see a cousin, the Duke of Spritzland.”

The man jumped as William mentioned their destination. “I know that house,” he said softly. “I am … I was … the butler there. But I fear you are out of luck. Today the house is being foreclosed on. The young Duke, unfortunately has a habit of spending time at the gambling tables. He inherited a tidy fortune from the old Duke, but his ways at the tables were not lucky. Five years ago today he mortgaged the house and his estates in Sussex. Other estates have been sold since, and by noon today he will be landless and homeless. That is why I am no longer the butler.”

“It is nearly five hours until noon,” Abigail said. “Surely we can do something?”

“Unless you have 3000 pounds handy, no,” the butler said. He looked startled as William smiled. They had walked back to the carriage, and the man stood outside as William climbed in: “Tell me, are your wages paid up at the house of Spritzland.”

The butler laughed. “No. None of us have been paid for two years. Several have left for other positions. I have not been paid for three years. The house owes money to all the trades, and the Duke has sold or pawned almost all the furnishings. There is no food at all in the house. We have been living on oatmeal from the stables for the past month, and today the cook said that was gone.”

“What was your salary there?” William asked. “Please get in the carriage with us. We will take you home.”

“I was to be paid £15 a quarter,” explained Hockings, as he said his name was.

“Sixty a year, three years … here is £200. I am in need of a butler. Would you serve me?”

“Yes milord,” Hockings said in amazement. “At what house?”

“The same one you have lived in for 40 years. I plan to buy it from my cousin. He and his family will continue to live there, but if I own it, and all the fixtures, then he will no longer be able to gamble it away. Now, if the larder is empty, we should stop at some shops as they open so that the staff and family can break their fast.”

It took a few minutes for Hockings to realize that salvation was at hand, and he directed James to a commercial district that was just starting to open up. No super markets in this time period, Abigail learned. You needed to go to a different shop for almost every product. One stop for milk, cheese and butter, another for bread. Meats were all in one location, staples in another. One more shop for root vegetables.

In almost every shop the owners nearly chased Hockings out of the store, until William showed them coin, and said that he was the one purchasing. He also told the shopkeepers that if they appeared at the Duke’s residence in the afternoon with evidence of the debt owed, then all arrears would be cleared. The only condition was that the Duke sell his home to William.

They arrived at the beautiful large mansion at about 7:30 in the morning, and found the place nearly deserted. Hockings ushered William into the Duke’s office, while the other three carried goods down to the kitchens.

“Who are you?” snapped the Duke as William entered. He was standing behind a small, cheap table. There were no chairs or stools in the room. “The mortgage is not due until noon. Are you that eager to put my household on the street?”

“I am not from the people you are dealing with in that matter,” William said, pulling a letter out of his satchel without revealing the other contents. “I am your cousin, William Currie of Stanstead, and have arrived with my sister Abigail. By chance we met your man Hockings, and heard of your dilemma.”

“Looking for a bed and meals, I suspect,” the Duke said bitterly. “Well I’m afraid that it is too late for either.”

“Perhaps not,” William said, grabbing a fistful of pound coins from the satchel, and setting them on the table, which held a large document that the Earl recognized as a mortgage promissory note. “May I?”

“Yes, certainly,” the Duke said, mesmerized by the sight of gold.

“This says you need to pay £3215 by noon today,” William read from the mortgage. “I think we can cover that. However, this is not a gift. I mean to buy the house and the Sussex estates with that amount.”

“So we are still out on the streets,” the Duke muttered. “I see no difference.”

“The difference is that you are family, and will continue to live in the house. I wish I could allow it to appear in your name, but then people would continue to come after it to cover gambling debts. So it will have to become known that I own the house and lands. I don’t seek your title. That will remain with you. But I will own the house, and run the house. Everything in the house will belong to me, even the clothes you wear. The servants will report to me, not you. I will allow you £10 a week for your gambling, no more.”

“Ten pounds?” the Duke roared. “That is nothing. I need at least £200 a night.”

“And that is why you are on the verge of being the first Duke of England to go to a workhouse,” William said. “That is my offer. Do you accept?”

The Duke only hesitated for a few moments, and then signed the bill of sale, with Hockings, and a woman named Bentley, apparently the housekeeper, witnessing it. She had arrived with food, although the cooked buns were carried on a slab of wood, all the actual platters having been sold or pawned.

“I was told that there was no food,” the Duke said, as he and William each took a roll.

“The larder is restocked,” Bentley said. “The cook is currently working on a dinner for tonight like we haven’t seen in months.”

The servants left, and the nobles swept the crumbs from the table, and started to work making stacks of one pound coins 50 high, eventually making 64 piles, with another smaller pile of 15 coins. It was shortly after they finished counting and recounting, that the moneylender who held the mortgage arrived. He was amazed to see the money sitting on the table. After the shock wore off, he smiled.

“I will gladly take cash for the house,” he said. “The estates in the country are worth more, but London houses are selling slow with all the troubles, and cash will actually suit me better.”

The man counted the coin twice, and at the end insisted that another £200 was due because it was now 12:45, and the mortgage specified that the payment be made by noon. He called for a penalty.

“The money was sitting on that table at 10 a.m.,” William said, his voice rising. “If anyone is to pay a penalty, it is you for making us wait while you dithered about the count. Anyone with the least bit of math skills could assess the total in two minutes, and you took over an hour. I think you owe us £200 for trying to extract more than your due.” William stuck out his hand.

“No, no, that is fine. I will waive the penalty,” the moneylender said. “Now let us sign the mortgage to settle it.” This time it was Hockings and William who witnessed the transaction, and the moneylender left.

“Sir,” Hocking addressed William, and not the Duke. “There are several tradespeople here to see you.”

“Ah yes,” William said. “Send them in according to how long they have been waiting.” You need not remain for this, milord,” William dismissed the Duke, who headed off to the kitchens to see what was going on down there.

“Before you call them in, Hockings,” William asked. “Do any of the staff read, write, and do sums?”

“I do, sir, and Bentley, of course. The cook has some expertise with money, but I don’t think she can write. Oh, Kensing in the stables is educated. I’m not sure why he is still with us.”

“Good. I want Kensing, and James, the driver who has our carriage, to go buy some horses and a wagon. Am I right in assuming that we have none?” The butler nodded. “Have the head of the stables go with them. Also …”

“Sorry to interrupt, but Jones, the stablemaster, left us eight weeks ago. He said he wouldn’t work at a stables that had no horses after the master … the old master … pawned them off.”

“Okay. But I also want another man, someone with some muscle. And who is the senior maid after Bentley?”

“That would be Winthrope,” Hockings said.

“Excellent. Have them come in to see me as soon as you can arrange it. And send Joe as well. They may need a runner.”

Williams got through the first three merchants before the staff he requested were ushered in. The merchants had been easy to deal with. They all came in with bills and accounts, expecting to have to argue just to get a portion of their money. The amount they were willing to pay as a discount for immediate payment varied from 20 percent to 50 percent. To their surprise, William merely scanned the accounts to verify that they seemed accurate, and then paid 100 percent for the arrears, rounding up to the nearest pound. When William told them that future accounts would be paid in full at the end of the month, they were all smiles and willing to do business with the house again.

When the staff popped in, William quickly explained that he wanted James to go to his masters and purchase four carriage horses, preferably the ones that he had rented for the day, and the carriage and tack. He also needed two more common horses and a work wagon and tack.

“Hmm, let’s see,” the driver said. “The boss will probably want £250 for that carriage. I know he paid £200 for it, and he’s rented it out several times. Carriage horses will probably go for £12.50 each. The troubles have driven up the price of horses something terrible. A decent wagon will cost you £50: the troubles again. Common horses will be £10 each. So you are going to be looking at £370.”

William was impressed at how quickly the man had toted up the prices. “Next question. There is a vacancy for stable master here. Are you interested in the job?”

“I might be. What’s the pay?”

“I can offer 13 pounds a quarter,” William said.

“I get 15 now,” James said. “But getting held up by bandits is a not an attractive part of the job. And next time there may not be people in the coach as good as you and your sister at quelling them.”

“The job includes room and board. Are you married? Children?”

“The wife takes in laundry. This kids are grown and have families of their own.”

“We might be able to find a position for your wife here. I am short staffed right now.”

“I’m your man then,” James said. “When do I start?”

“Right now, if your current boss doesn’t need notice.” William took £400 from the satchel, and was surprised to see that it was full again in spite of nearly £4000 being taken out for the mortgage and payments to the suppliers.

He reached in and took out another £500 and handed it to Kensing. I want you to take the wagon and team that James will buy you, and head out and try to find some furniture for this place. Winthrope is with you because she will know what is needed. Beds are of importance. I’ve slept on a hard floor before, but don’t relish doing it again. A wardrobe for my sister. Whatever is missing from the rooms of the Duke, Duchess, and their daughter. Cleaning supplies if we need them. Everything that we need to get this house livable again. Have things sent on if the vendors can, otherwise pile them on the wagon. Send Joe back if you need more money. If you see anything that is from the house, I want it. Buy it if it is reasonable, but make note and let me know if it is not. I may overpay if it is an important part of the house’s heritage.”

After they left, there were eight more vendors to settle up with, and again all left with large smiles and full pockets.

“That was the last,” Hocking said after leading a merchant to the door.

“Good. I guess the next step will be to have a staff meeting. I would like to have all the staff get together so I can address them. Where would be a good place?”

“The Great Hall,” Hocking said. “It is where banquets and dances were held by the old Duke. It is not much used any longer. But I’m not sure this is a good time, sir. The kitchen will be well underway for dinner and cannot just leave pots and roasts.”

“Of course,” William said, slapping his head. “And I just sent a bunch of staff off an hour ago. We will do the meeting after supper.”

“That would be better, sir. There is still much to do in the kitchens then, but it is washing up, and that can wait, while cookery cannot.”

Just then a footman appeared. “Sir, milord, there is a wagon out front with furniture on it. Do we have an order coming in?”

“Many orders,” William said. “Bring it in.” That first load contained a fine dining room table, as well as another table that was immediately taken to the kitchen, where the staff cheered to have a work surface back to prepare on. William noticed that some of the undercooks were sitting on the floor, with mixing bowls between their legs. The Duke had totally gutted the place.

The good table went into the dining room, and there were four chairs, as well as two long benches for the sides. One four-poster bed was brought in, and placed in the room that Bentley said would be Abigail’s. The next wagon to appear was from a mercer, and contained curtains, towels, linens and bedclothes. It also included several mattresses.

The last wagon was driven by Kensing, with Winthrope sitting beside him. It contained a beautiful desk for the office, which apparently had sat there for 60 years before the Duke sold it. There was also another four-poster bed, so William would not be sleeping on the ground, and the final piece of furniture was a wardrobe that Winthrope thought would work in Abigail’s room.

“Good job all,” William told them. “I want you to go out again tomorrow, and do it all over again. We have a lot of money to spend to get this house looking reasonable again.

- Emerita is the feminine of Emeritus, the term for a professor who has passed the normal retirement age, but maintains a connection with the university, often a reduced teaching schedule.

- Countess is the proper term for the female Count or Earl. There is no Earless, which is a term for a person without ears.

- A cabriolet was a small, light conveyance pulled by a single horse and holding two people (and a driver). The present term ‘cab’ comes from this term.

- The ‘boots’ was a servant, usually a young boy, who was responsible for getting up early in the morning to take any boots that had been left outside of the doors of a room, and polish them, if leather, or brush them clean for other types. The clean boots were to be back at the doors of the patron when he woke up. In the case of a hotel, or when visiting another house, a visitor would drop four pence or so into the toe of one boot as a tip.

If you liked this post, you can leave a comment and/or a kudos!

Click the Thumbs Up! button below to leave the author a kudos:

And please, remember to comment, too! Thanks.

Comments

World?

If anyone is interested in entering this world to write a story, send me a note. I would particularly like to see someone do the music faculty experiment about going back to see the Beatles in their Cavern/Hamburg days ... as attractive females. Could be a great deal of fun reliving the days of Love and Music.

Dawn

Great Start

Really "interesting" story so far. Thanks for sharing.

Interesting times

A very interesting start. I have to admit I almost skipped over this story as I have been put off time travel after a few tv shows jumped the shark with it. I should have trusted the author. River hasn't disappointed me with a story yet. I have thought that even though the crucifixtion is a tempting place to start timetravel it is not a good idea to try to get evidence of an event that is meant to be taken on faith. This is almost guarenteed to end badly.

Time is the longest distance to your destination.

If you like this story

then I would recommend you take a look at Marine by Tanya Allan. The plot is similar, save that they are trying to prevent an enemy time faction from destroying our time line, rather than doing basic research. The writing is every bit as good and the story has a similar feel. And for some unknown reason the alien artifacts allowing for time travel flatly refuse to transport people to within about 50 years of the crucifixion so I guess Tanya Allan agrees with your opinion. (Dont fortget. If you decide to buy the book from Amazon then go there through the BCTS link so they get a commission.)

Interesting times

Abject apology. I wrote River instead of Dawn Natelle. This is why I have deep respect for people who can sucessfully proof what they write. I even previewed it and still messed up. Again sorry and I look forward to your next chapter.

Time is the longest distance to your destination.

dawn

dawn strikes again. you are off to a great start. keep up the good work.

robert

You've done it again.

I found both River and A Second Chance to be riveting stories that I eagerly followed. And now I am eagerly following this one too. Thank you.

Looks

Like there is tons of possabilities with this new story..

I do enjoy time travel along with gender-corrections..

Eye opening when you find no matter the time or culture.. ones inner self demanding aa female life.

alissa

oK i'm hooked

and waiting for more.

Interesting times

Wow, you have certainly did some research on historical references for this story. I can say I am definitely going to be looking for the next chapter.

Hawkimg time machine?

I realize that the McGuffin that is used to travel in time makes no real difference to the story, but to the best of my knowledge Stephen Hawking never designed a time machine, and is very unlikely to have ever have done so -- he had a very strong aversion to time travel. Kip Thorne did design a time machine (Michael S. Morris, Kip S. Thorne, and Ulvi Yurtsever, Phys. Rev. Lett. 61 p1446), but it can't be used the way the time machine in this story is used, since it can't be used to go back to any time before the machine was first built.

If an author wants to use a time machine to travel into the past, just hand-wave it.

Oh?

Look into this article where Hawking describes his time machine http://www.dailymail.co.uk/home/moslive/article-1269288/STEP....

Dawn

Hawking

Hawking is just using Lorentz time dilation to slow one's personal time. He did not invent this; it was in Einstein's original 1905 paper where he presented special relativity (A. Einstein, Ann. Phys. 17 (10): 891–921). It is not what most people would consider a time machine, as it only goes into the future. Thorne's time machine, on the other hand, is a real time machine, in that it allows travel from a future time to a past time. There is a limit, in that you can not travel earlier than when the machine was first built.

A remarkable story

I'm looking forward to reading more about jolly old England back in the 1600's. British coinage ALWAYS boggles my mind but being from the states....

Love Samantha Renée Heart.

Pounds, shillings, and pence

Pounds, shillings, and pence aren't all that difficult - even children in Britain mastered that before decimalization. However, in the 17th century, a shilling was a lot of money, which is why they even had farthings (one quarter of a penny). Oh, and don't forget the guinea. In 1965 I purchased a Crombie tweed jacket at R W Forsyth on Princes Street in Edinburgh for 10 guineas. I'll leave it to you to do the math for that one, except in 1965 a guinea was about $3 U.S.

British currency was boggling

British currency was boggling because until they went over to the decimal system based on TENS like everyone; their currency was based on the TWELVE system. You really had to learn and know your multiplications through the 12s to figure the money. I remember back during 1953-1956 when I lived in England, that our mother would take either me, or my brothers or our sister with her to go shopping in the local shops and stores, because we would do the money for her and give her the rate of exchange that she needed to figure if she was getting a good deal or not. She finally had it figured out by the time we left to come back to the US.

Then signs for penny (pence) used a "d" on them. NEVER figured that one out. There were also the Two and Six coins (Two Shillings/Six pence). 3 Pence coins, 6 pence coins, Farthing (1 quarter of a Penney) Pound (also called Quid) and so forth. At the time, it was $2 dollars, 80 cents to the Pound Sterling. There were names used as well on the money, that took some time to learn. But it was truly fun, at least for me.

Love England however and not just because I have relatives there either.

Denarius

The use of "d" for pence was derived from the denarius, a silver coin of the Frankish kingdom. There were 240 pence in a pound sterling, or 20 shillings of 12 pence each. The two shilling and six pence coin was a half crown. At one time crowns (five shillings) were also minted, but they were obsolete by the time I first visited Britain, as were farthings. However, half pence were still in use then. The UK did, however, issue a crown coin to honor Winston Churchill in 1965.

Most became obsolete with decimalization, except the shilling, which became 5p. and the florin (two shilling coin) which became 10p. The pound sterling was still the same, but divided into 100p instead of 240d. Since the smallest coin was then several times larger than the previous smallest coin, prices for small items jumped.

"p" and "d"

These two letters have an unusual visual relationship. (Perhaps the "d" thing was the result of a dyslexic decision maker?)

If you rotate a "p" 180 degrees, it becomes a "d". And vice versa, of course.

For example, consider the word "up". Now rotate it 180 degrees.

up

dn

Try it yourself. Write either word on a piece of paper. Now rotate the paper 180. And rotate it again. And again.

Have fun.,

T

"dn" isn't actually a word, of course. But it is a common abbreviation that almost everyone knows, so many of you will not have objected (until now) to my example on the basis that "dn" is not really a full word.

Life is strange. And fun. If you loosen up just a bit.

Great first chapters!

Looking forward to more of this story. I feel for the poor earl and countess (time traveling and transitioning) although they both seem to be handling it like champs. Definitely I feel for the new countess more than the earl after all just being a girl in the 1600s was really really miserable. I will admit to giggling at "Earless" I never thought that was wrong but I also never spelled it...

The story concept is very

The story concept is very interesting. I have enjoyed the River other story by Dawn.

The only issue I have is the intro concept as to the religious travels and mocking of religious concepts of Christianity. It was an abrasive start to a story for anyone with christian beliefs.

Interesting Times Indeed

Wow.

Thank you Dawn. This story has me hook line and sinker!

The story is very entertaining to read

It brings home how difficult the times were, but the people serving the Duke just lucked out big time. I'm very interested to see how the protagonists progress in their new surroundings.

A really bang-up

Story. Despite coming late to the party I expect to have a good time reading this. Douglas/Abigail seems to be slipping a bit into female mannerisms, I wonder what she'll be like if she stays the 50 years originally planned. Does the professor have an ulterior motive perhaps?

“When a clown moves into a palace, he doesn’t become a king. The palace becomes a circus.” - Turkish Proverb

I remember this story well

I remember this story well. I also remember wishing there were more chapters. Mind you, I tend to have that wish for a number of Dawn Natelle stories but the two stories I am greedy for the most is this one and A Second Chance.

Dawn Natelle is an awesome author.

Still wishing.

I have long lost track of how many times I've read A Second Chance and Interesting Times. I've read Dawn Natalie's other stories but these two stories really touched me and are among my go-to stories when I am looking for comfort reading.