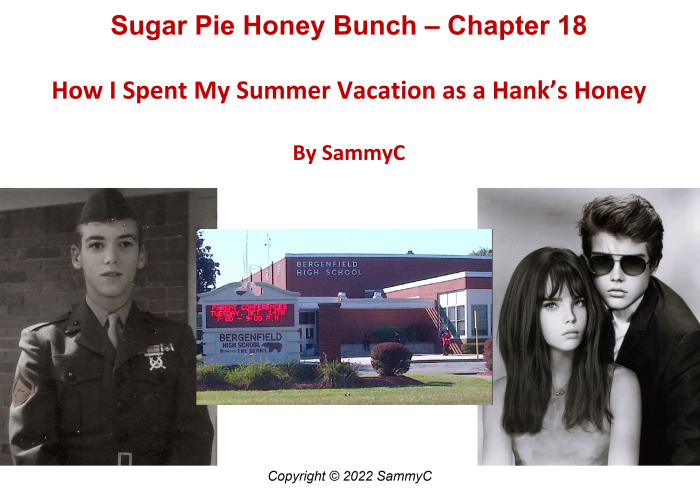

Sugar Pie Honey Bunch

Author:

Audience Rating:

Publication:

Genre:

Character Age:

TG Themes:

TG Elements:

Permission:

I walked all the way home from school instead of taking the bus as I normally did. That darn song by The Four Tops was still ringing in my ears, giving my walk a bouncy step and a swing of the hips. It was the hip swing that started the whole thing and made my summer the most memorable of my whole life…so far that is.

It was Tuesday, September 6, 1966, the first day of my senior year of high school and I didn’t relish having to explain to my friends why I had been missing in action for three months, from graduation day until the Friday before Labor Day.

I was dressed in a freshly ironed white button-down shirt, brown cotton velour trousers and brown wingtip oxfords. Dad had forbidden me to wear what I really wanted: a paisley print peasant blouse, powder blue hip-hugger mini-skirt and white vinyl go-go boots. I mean, really, I am 17 years old, after all. Okay, I’m a boy, not a girl. Well, it’s a long story.

My name is Itsuki Brennan. But everyone calls me Shuggie or Shugger. That’s because my big sister Connie had trouble pronouncing my name and my dad preferred Shuggie to a Japanese name he couldn’t explain to American friends and family. If Dad and I were out somewhere without Mom, he’d just blithely tell people I was Black Irish.

My Mom, Eriko, met Dad after the War in Okinawa where Corporal Gerald Brennan was stationed as part of the Allied Occupation. She was a war widow and at the age of 24, she eagerly accepted my father’s marriage proposal. Her parents weren’t ecstatic about their daughter marrying a gaijin, but they knew her life prospects were exponentially better halfway across the globe than in the backwater post-war uncertainty of Okinawa. Mom was already pregnant with my sister on the plane ride back to the States and, three years later, I joined the Brennan clan here in sleepy suburban Bergenfield, New Jersey.

“Why are you dressed like that, Itsuki-chan?” My 70-year-old grandmother was working on our vegetable garden, practically on all fours, a spade in one hand, dressed in what looked like, to Western eyes, pajamas, a floppy beach hat and wellies.

“You know it was my first day back at school, sobo.” She and I conversed in a cute hybrid of English and Japanese. It was a private language between us that we’d spoken ever since my parents brought her over from Okinawa after grandpa died 10 years ago. My big sister never bothered to learn. The only Japanese word she knows is her own given name, Kanako, but she prefers to be called Connie at Rutgers, where she’s a junior business major.

“I can’t understand why your chichi insists you dress like a boy when everyone knows you’re a girl. Things are so strange here in this country.” She wiped her brow and shook her spade at nothing in particular.

“We’ve talked about this before a million times, sobo. Dad will never see me as a girl. And Mom just goes along with everything he says.”

“Your sobo is getting old and senile, chisana nezumi. Tell me again where you’ve been all summer? I thought you had run away with your boyfriend and never coming back,” she sniffled and walked over to me.

“My boyfriend? He’s not…why would I do that, sobo?”

“You love him. I have eyes. I can see.”

“But I can’t marry him…”

“I know. Your chichi would never allow it. He doesn’t like the boy and he thinks you’re too young. But your mother was married when she was 17. Like you are now, Itsuki-chan. Poor Haruto-san. He was only 20 when…” She stopped, seemingly lost in memory.

“Well, it’s a moot point. Bobby is in boot camp right now. He might be fighting in Vietnam next year. And he’ll probably forget all about me . I don’t think I’ll ever love anybody as much as I loved him.” Tears started streaming down my cheeks as my grandmother wrapped her arms around me, pressing her head against my chest and cooing softly.

We stood there in the garden, like that, for what seemed hours but, after a few minutes, I had gathered myself enough to ask, “So you really want to know what happened?”

“Yes, child, tell me again for the first time.”

The second they handed his diploma to him, Bobby Gene Messina leaped off the stage of the Bergenfield High auditorium, tossed his mortarboard into the air, tore off his academic gown and made a mad dash for the exit. On the way, he passed his astonished parents, bored younger twin sisters, my parents, and, most importantly, me, his best friend forever and a year younger, Shuggie Brennan. While they all remained stuck in their seats from the sheer shock of it, I jumped up, almost stumbled over my dad’s feet, and ran after Bobby. Although Bobby was several inches taller than I, from the time we were in elementary school I could always beat him in a foot race.

I caught up to him just as he opened the driver’s side door of his new Cherry Red Chevrolet Corvair Corsa. The one his dad had bought him for graduation. He was so proud of his son and was sure he’d play first chair oboe for a famous symphony orchestra someday soon. After finishing his conservatory studies, of course. But Bobby had other plans.

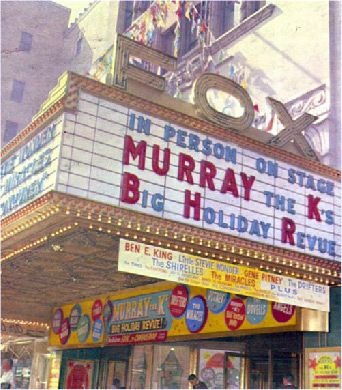

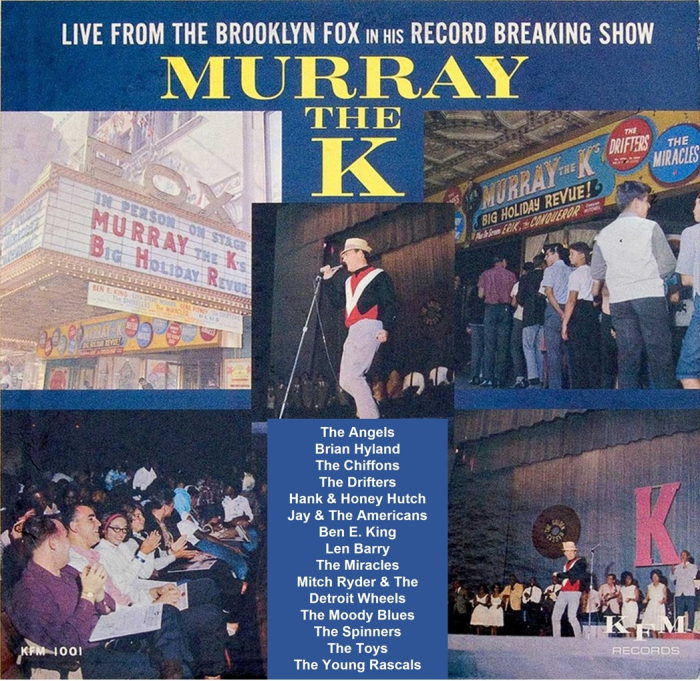

Bobby was going straight into the music business, playing tenor sax for one of genius producer Billy Schechter’s famous acts, Hank & Honey Hutch with Hank’s Honeys. They were touring the country that summer. A package show headlined by Hank & Honey and supported by other rockin’ artists who were just emerging onto the charts. Schechter’s scouts had discovered Bobby playing local gigs in bars and clubs ever since he was an underage 16-year-old. He’d even lied to his parents about attending Junior ROTC weekend camps at Fort Dix so he could sit in with bands in Newark or even New York City. We would have to sleep in the car unless someone let us crash in their pad. Of course, I went along to support his story and my dad was very proud of me, although Mom was hoping the Vietnam War would be over by the time I was of draft age. The tricky thing was obtaining hand me down ROTC uniforms. Fortunately, Bobby had cousins who had gone off to college. My uniform was just a little too big. And the cap fell over my eyes at every opportunity.

“Where do you think you’re going, shrimp?”

I dove in past him and struck a triumphant pose as he shook his head and climbed in behind the wheel.

“I told you I can’t take you. Your dad will kill me if he ever catches up to us. I’m taking you back to your house.”

“Good. I need to pick up my suitcase. If you’re hitting the big time, your girl can’t be caught wearing the same old dowdy threads. I’ve got some new outfits! “

He snickered when I said “your girl” and just started the car. True to his word, we moved at high speed toward my house, which, of course, was next to his. Our dads both worked at the Marcal Paper factory in nearby Elmwood Park and moved onto our block just months apart from each other.

“I’ll just be a minute, Bobby.”

“I’m not waiting, Shuggie. I’ll be late for rehearsal. I told Schechter I’d be there by…shit, I’m already half an hour late. Just forget it, Shug. I can’t take you.”

I stood there and looked like I was about to burst into tears. My hands went to my face because I knew the blood was rushing to my cheeks. I burbled something unintelligible.

“Okay. Okay. Jesus, Shuggie, turn off the waterworks. Get your suitcase. We’ll think of something tonight. I’ll drive you back. But get a move on. Can’t lose my job before it even starts!”

I ran into the house, climbed the stairs two steps at a time, went into my room and hauled out my suitcase and makeup case (kept hidden from my dad but Mom knew about it). Rushing out, I hugged my grandmother as she shuffled into the living room, carrying a cup of tea. I placed my index finger against my lips.

“Ima wa hanase nai, sobo.”

The door slammed unintentionally as I flew out to Bobby’s car. We drove off in the opposite direction just as my parents’ car turned the corner onto our block, followed right behind by Bobby’s family car. I giggled and immediately hunkered down in the back seat, out of sight.

“Not funny, Shuggie. Hey, what are you doing back there?”

“Changing. You’ll see. Don’t look in the rearview mirror. Be nice. You’ll see when I’m ready. Ooof. Can you not drive like a maniac? I don’t want to poke out an eye here.”

“If the traffic’s not bad, I can make Times Square in 40 minutes. I’ll be an hour late but Schechter’s gotta give me some slack. He knows I’m good. Hey, are you really wearing ear rings?”

“Don’t look I told you! Just keep your eyes on the road, buster.”

“I wish I’d never told you I thought you were too pretty to be a boy. Jesus, look at you now.”

“I’ve always felt more like a girl than a boy. You know that. My mom knows that. Even my grandma. It’s only my dad thinks I’m a pervert.”

“Speaking of which, Shug, I’m no homo. I mean, you’re my best buddy and all, but I’m not into guys. How many times do I have to tell you?”

I popped my head up from the back seat and fitted my wig on. Shaking it from side to side, I reached over and pulled down the visor mirror.

“Good thing I combed it out this morning. Whatcha think, Bobby?”

“I think you need help.”

“I think I look nice. Tell me I’m not prettier than Rachel Hanley.”

“Well, she’s a girl. You’re not.”

“Did you do her in this car? Like in the very back seat I’m sitting on? Oh, lord, the thought.”

He ignored me as we crossed the George Washington Bridge and exited onto the Henry Hudson Parkway. All the way down the West Side of Manhattan I could see the forest of buildings that hid the heart of darkness named New York City. It was exciting to escape the black and white dullness of suburbia and throw ourselves into that dangerous, mysterious, but oh so glamorous city that lay waiting like a predatory beast to devour us.

Bobby parked the car a couple of blocks west of 1619 Broadway, otherwise known as The Brill Building, home to music publishers, talent agents, and songwriters. We left our bags in the locked car. I wasn’t too sanguine about the surroundings. They didn’t call this Hell’s Kitchen for nothing. Bobby carried his saxophone case with him. I tried to hold his free hand as we walked but he kept switching his case from side to side, making it a frustrating shell game. He avoided looking at me. But, really, no one even gave us a side glance. I think I was totally convincing as a teenage girl. Because, well, I am one. Really.

There was no one in the lobby of The Brill Building. Not even a doorman. Like the ones in the paramilitary uniforms with epaulettes you see on TV. Bobby moved over to peruse the Lobby Directory but turned away, a confused look on his face.

“Cripes, I don’t know the name of Schechter’s company. Can’t see the record label name on here either.”

“Nice planning, Brainiac. What do we do now?”

At that moment, a couple who looked like they were in their mid-twenties, casually dressed, the man in a corduroy blazer, a pipe dangling from his lips, and the woman in a sweater and plaid A-line skirt, walked into the lobby from outside. Bobby tried to make himself smaller and not attract their attention, but I boldly walked up to them. What the heck. Maybe they know this guy Schechter.

“Excuse me. Can you help us out here?”

“Hey, no panhandling, kid.” Turning to the woman, “Where in the hell is that security guy? Another two-martini lunch?”

“Not likely on his salary, Gerry. Don’t mind him, miss. How can I help you?”

“We’re looking for the offices of Billy Schechter. He’s…”

“Yeah, we know who he is. He doesn’t have offices here.”

“They’re using younger and younger bagmen these days? Look, Carole, a couple of suburban teens. They even gave one a saxophone case to carry. Very convincing.”

“Cut the comedy, Gerry. This Billy Schechter you speak of, what is your business with him, may I ask?” Gosh, these two had some thick New York accents. Like out of The Honeymooners or something.

Just as Bobby found the spunk to open his mouth, a tall, slender man in his mid-twenties, wearing a dark three-piece suit and a tan-colored fedora, burst out of the elevator.

“Hey, Billy, a couple of bagmen here looking for you.”

Schechter almost fell back into the elevator, but the doors had already closed behind him. He took a look at us and laughed.

“You had me for a minute, Gerry. Carole, nice to see you. Forsooth, what do you kids want?” He started reaching into his pants pocket. You could hear loose change jingling.

“Mr. Schechter, I’m Bobby Messina. You know, tenor sax?” He hefted the case into view.

“You’re an hour late. Lucky for you I came over here on the likely chance you didn’t know your ass from the rehearsal studio. Come on, the studio’s at 1650 Broadway. I’ll introduce you to Hank and the boys.” He walked quickly toward the doors, waving Bobby to follow.

I was left alone in the lobby with the couple I knew as Carole and Gerry. We exchanged looks. I’m sure my face betrayed my sense of abandonment.

“I’m Carole King, by the way. This is my comedian husband, Gerry Goffin. You may have heard of us?”

I shook my head and tried to not convey my embarrassment. I couldn’t find a good place to put my hands. I would have whistled if I could. But I can’t. Finally, Carole took me by the arm.

“We’re going up to our office. Wanna sit and watch us write a song or two? Billy’ll bring your boyfriend back here after rehearsal’s finished. What’s your name, sweetie?”

The phone rang from inside the house. My grandmother jumped as if startled. I ran in and picked up on the third ring. It was Mom.

“Hello, honey. Your father and I are going to visit your Aunt Brenda tonight. You know she’s just gotten home from the hospital. Needs some help. Your uncle is just useless. We won’t be back until late. Anyway, I’m at the paper factory right now, waiting for your dad. Have sobo make dinner or order pizza. Let her decide. Bye. Love you.”

My grandmother had just come into the house. “Was that your okaasan? What did she want?”

“She said to order pizza.”

“Good, chisana nezumi, then you can continue your story while we wait. I love pizza. Make sure to order the one with pineapple.”

Sugar Pie Honey Bunch - Ch. 2

Author:

Audience Rating:

Publication:

Genre:

Character Age:

TG Themes:

TG Elements:

Permission:

“I didn’t know that pizza came from Hawaii,” said my grandmother just before she took a large bite out of the last slice left in the box. I was already miffed at her for swiping it before I had even reached out my hand.

“It’s not from Hawaii, sobo. I heard the pineapple topping started in Canada.”

“They grow pineapples in Canada? Isn’t it cold up there? Even colder than here in New Jersey?”

“They import the pineapples…look, let’s get back to my story.” I was still kind of hungry. So, I went to the kitchen and took the half bottle of soda out of the refrigerator and poured myself a glass. At least I could quench my thirst.

“Fine with me. It’s better than watching television shows I can’t understand. But I must say, koneko, the commercials are hilarious.”

I looked at the framed gold records and music industry awards on the walls of their surprisingly small 8th floor office. There was barely enough room for a piano, a roll-top desk, and a few folding chairs. Carole had already sat herself at the piano, turned toward me, while Gerry nervously paced. It was then I realized the room didn’t have any windows.

“Shuggie, huh. That your given name or a nickname?”

“Well, my name is really Itsuki. Itsuki Brennan. Shuggie is a nickname my stupid sister gave me when I was a baby because she has some kind of undiagnosed speech defect.”

“I’m sure you’re kidding. Shuggie’s a cute name—”

“For a girl?” Gerry gave me a sympathetic look and sat down on one of the folding chairs. He re-lit his pipe and took an exaggerated puff. “Johnny Otis’ son is named Shuggie. He’s a 12-year-old boy.”

“So, are you just here for the day?” Carole inquired.

“Oh no, you see, Bobby, that’s my boyfriend, except he doesn’t know we’re…uh…involved. We were supposed to be together for the summer. You know the tour with Hank & Honey. Then he tried to run off without me today after graduation. His graduation, not mine. I’m a senior this Fall…”

Gerry interjected between puffs, “You’re 17? That’s really young, don’t you think? Looks like your Romeo made a smart call.”

“Hey, I was 17 when we got married, mister.”

“That’s different. You were knocked up. I had to make you an honest woman.”

Turning away so they couldn’t see me blush, I said, “Well, there’s not much chance of that happening to me.”

“Shooting blanks, eh? Well, ladies, I’m gonna go over and talk to our fearless leader. He said he wanted us to write songs for some kiddie show the guys in La La Land are cooking up.” He strolled out after one final puff of his pipe.

“Don Kirshner’s the music supervisor for The Monkees TV show. It’s premiering on NBC this Fall.”

“Oh, yeah, they’re on the cover of Tiger Beat this month. Bobby doesn’t like that sort of music. He’s into Miles Davis and John Coltrane…whoever they are.”

“Well, he’s not going to play anything like that if he’s in Hank & Honey’s band. But everyone’s got to start somewhere. I should talk. Gerry and I wrote some treacle early on. Just to get a foot in the door.”

I was barely listening and started to quite unconsciously pace back and forth. Carole followed me with her eyes. I stopped and said to the wall, “Do you think they’ll let me in to see Bobby in the rehearsal studio? I’m afraid he’ll just forget about me and leave me stranded in the middle of Manhattan.”

“I don’t think he’d do that, Shuggie. Look, when Gerry comes back, I’ll walk you over there. It’s just up one block.”

“Thank you, Carole. I’d just die if I can’t spend the summer with him. I’ll lose him forever. He’ll go off to college or worse, he’ll actually play music for a living. There are lots of more…uh…mature girls out there. He’s the only boy I’ve ever loved.”

Carole turned around to face the keys of the piano and started playing the opening chords of "Go Away Little Girl": D, G, Em, G. I recognized it as a big hit for Steve Lawrence when I was in Junior High. Carole turned to me whenever the chorus came around, smiling, and winked.

When you're near me like this

You're much too hard to resist

So, go away little girl

Let's call it a day little girl

Please, go away little girl,

Before I beg you to stay.

“Your Bobby’s going to beg you stay. You’ll see.”

At that point, Gerry came back into the room, a scowl on his face. “Effing poohbah isn’t in today. Something about his daughter’s college graduation.”

“So, you had a nice long chat with his secretary instead, right? Let’s go, Shuggie, I’ll get you in to see your precious Bobby.”

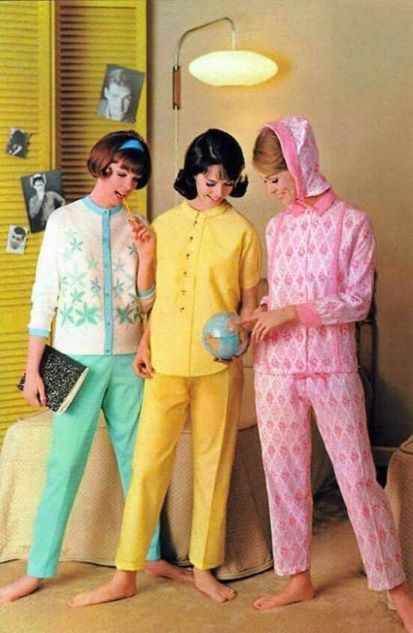

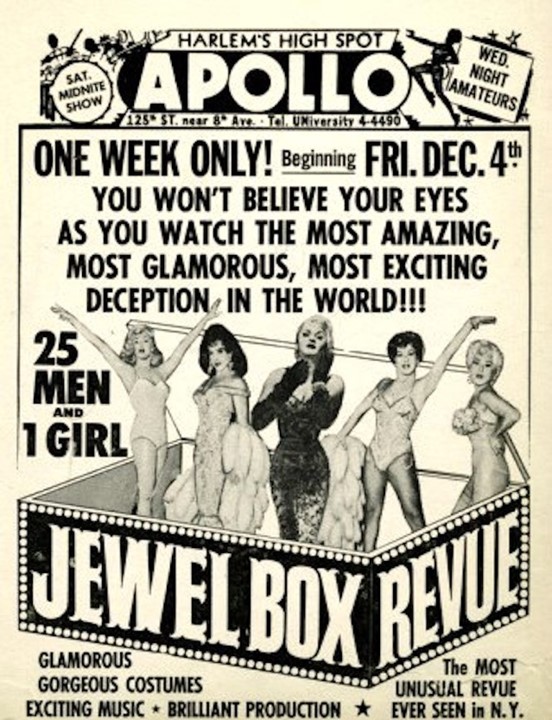

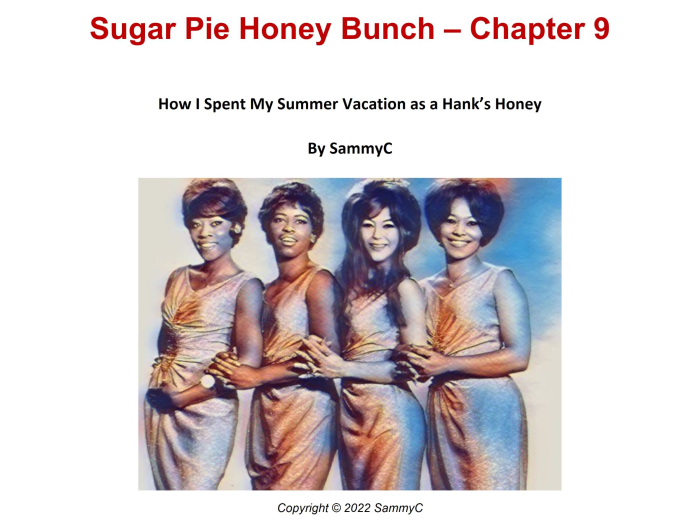

Bobby was wailing on his saxophone when I walked into the rehearsal studio. The band was playing a soulful up-tempo arrangement of The Beatles’ latest hit, “We Can Work It Out.” Honey Hutch was singing without a microphone but her voice had plenty enough volume not to need one in this cozy studio. Hank’s Honeys, three young women dressed in casual tops and clamdiggers, lounged in folding chairs, singing back-up. The acoustic paneling on the walls didn’t totally suppress the band’s sound. I could hear them, albeit slightly muffled, as I approached down the hallway. Billy Schechter was standing by the doors, puffing away on a Marlboro. He seemed happy. Without a word, he opened the near door and shooed me in. He followed behind me.

When Bobby caught sight of me, he winked. Didn’t miss a beat though. Hank Hutch, a tall thin Black man with a finely trimmed goatee and slick, processed hair, was strumming away on his electric guitar, a gold Gibson Flying-V model that he played left-handed just like Albert King. When the song ended, he noticed me standing next to Billy by the doors.

“Hey, who’s that?” he shouted as everyone turned to look at me. Stupidly, I pointed at myself while swiveling my head to see who Hank was addressing.

“It’s cool, Hank. Just a friend of your new sax player. Don’t mind her.” Billy nodded toward me and dropped his filter tip to the floor, grinding it out with his cuban heel boot.

“Okay, fellas. Break. 10 minutes, tops. We’ll do that new number Chubby brought in.” Hank beckoned Billy over to him and they spoke in hushed tones. Something they didn’t want the rest of the group to overhear, I guess. Honey and the girls walked past me, giving me the side eye, as they went to the powder room en masse. Which reminded me I had to go myself. Maybe later would be better, huh?

“Hey, I was going to come looking for you the next long break we took. But here you are.” Bobby had a big smile on his face. Was it for me? Or for the fact he was fitting right in with Hank’s band?

“Carole walked me over and got me in the building. You look happy enough…to see me?”

“Sure.” He took me aside as a couple of the band members slapped Bobby on the back as they made their way toward the table in the corner of the room set up with a pair of electric coffee urns. “Listen. I called home and talked to my dad. He told me your parents are hot as lava. They think I kidnapped you. Dad knows I never intended you to come with me. It’s all your idea.”

“You think I’d just wait by the phone for you to call from Chicago or wherever? Maybe a couple of those “wish you were here” postcards?”

“Shuggie, you know what I’m saying.” Hank walked by us, pointing at his watch. “After we’re finished today, probably around 8 or 9, I’ll drive you back home. I’m praying your dad doesn’t own a shotgun.”

“Nah, he still has his Colt M1911 from the War…”

“Shit!”

“But I’m sure he’s out of ammo for it.”

“He’ll just pistol whip me to death instead, Shuggie.”

For the next five hours I watched them rehearse their hour-long set. Several times. Hank Hutch was a taskmaster. He screamed, bellowed, cajoled, even threatened with physical violence…and that was just with the women! He even called out Bobby a couple of times for missing a cue. I winced as Hank tore into him. But Bobby was stoic, just nodding and keeping his head down. Some of the other band members, especially Chubby the piano player, would talk back to Hank, sometimes erupting into loud shouting matches filled with expletives I’d never heard before. But, then again, I’m just a shy flower of a girl in whose mouth butter wouldn’t melt. No, really.

Around 7 o’clock, Billy had some food brought in from the diner across the street and we all chowed down. I was ravenously hungry. No solid food since breakfast. Just cups of awful tasting coffee. Honey Hutch plopped herself down in a chair next to Bobby and me. She gave me the once over before opening her mouth.

“Do you sing or dance?” I nodded, not in answer to her question, but impressed by her look. She was wearing huge loop earrings and her wig was wrapped in a colorful floral print silk scarf. She had the longest fake eyelashes I’ve ever seen. “So, when do we hear what you got?”

Bobby interjected, “She doesn’t sing or dance. She’s going back home tonight.”

“Too bad. You know, Hank really goes for young stuff. I was just 16 when we hooked up. He was playing a club where I grew up. In Tennessee. Ever been there?”

I stuttered out, “No, I’ve never been outside of New Jersey really.”

Honey stood up and looked down at me. “Well, nice to meet you anyway. Shuggie, is it? Hmmm. Never heard that name before. Not on a girl.” She walked away.

Alarmed, I whispered to Bobby, “Do you think she knows? About me, I mean.”

“Don’t worry your pretty little head about it. You’re going home tonight.”

Suddenly I’d lost my appetite. I gave the rest of my meal to Bobby. He quite happily shoveled it onto his paper plate.

We walked quickly to where Bobby had parked his car earlier that day. It was dark. For some reason the streetlamps in this area didn’t shed much light on the street. I stumbled a few times trying to keep up with Bobby. He was carrying his sax case and keeping his free hand away from me. My skirt was too tight to increase my stride. I felt like shouting for Bobby to slow down but I didn’t want to draw more attention to us. Some of the pedestrians here gave me the willies.

There was a parking ticket stuck on a windshield wiper. “Oh shit, I got a ticket.”

“You’re lucky it’s not up on blocks and the trunk jimmied open. Where are we staying tonight?”

“You’re going home. This time of night, I can get you there in half an hour.”

I tried pleading, stamping my feet, even shedding a tear or two but Bobby was adamant. Thinking quickly, if not entirely wisely, I ran. Ran in a serpentine manner. Just like in the movies. It tends to confuse whoever is trying to catch you. At least in the movies.

“Shuggie, come back! What the fuck are you doing?”

I zigged and then zagged. I must have lost him when I zagged around a corner. Then, it occurred to me, I was lost myself. Afraid Bobby was just steps away, I dashed into the nearest subway entrance, almost tumbling down the stairs and colliding with a young guy wearing a NY Mets baseball cap.

Out of breath, I said, “Sorry.”

“No problem. It was my pleasure.” He doffed his cap and continued up the stairs.

I knew where I wanted to go. Would this subway take me there? I looked around for a friendly face. An older woman approached me.

“You look lost. Can I help you?”

“Yes, I’m trying to get to Sheridan Square. Can I take this train?”

“Well, you can take the 1 train to Christopher Street. You can walk to Sheridan Square from there. May I ask what a young girl like you is doing in that part of the city at this time of night?”

“Oh, I’m going to see my sister. She’s here for the summer. I’m from Bergenfield, actually.”

“Surprise visit then? Hmmm. You should’ve called ahead. That part of town is quite dangerous, especially for a dainty little girl like you.”

“I can handle myself. I wrestled in school.”

“They have girls’ wrestling in New Jersey?”

“Oh, no. I wrestled with the boys.”

“Are we talking about the same thing, miss? Oh, look your train is coming. Here, take this token. You won’t have time to buy one at the booth.”

Grabbing the token, I waved to the lady, dropped the token into the slot and went through the turnstile. The doors of the subway car closed just as I stepped in. With a lurch, we moved out of the station. The passengers looked up and gave me a brief glance before going back to what they were doing before I appeared. I could see I was no longer in Bergenfield. That was for sure. They say New York City is the melting pot of the world. Exhibit One would be the subway car I was standing in. Every race, ethnic group, old, young, rich, poor, men, women, children. They were all represented in that car. And, of course, one special girl. Me!

While the subway proceeded through the seven stops to Christopher Street, I sat in a window seat and berated myself for having to do what I was about to do. Seeking my sister’s help. Connie was in the city for the summer, interning in the sales department for a major pharmaceutical corporation. Probably getting coffee and answering phones, ha! And getting paid less than the girls in the typing pool. Big deal. Anyway, she and her friend from Rutgers were both in that internship program and sharing a small apartment in the West Village for the summer. Mom and Dad were very proud of her and had implicit trust in her spending three months by herself in the big bad city. Knowing her, she was hitting the discotheques and sleeping with every Tom and Dick she met. She’d leave the Harrys to her roommate.

When I emerged from the station at Christopher Street, I could see Sheridan Square about three blocks southeast from where I stood. I had been here just two weeks ago as I got dragged along with the whole family (even sobo) in Dad’s car when Connie moved in. It was a furnished apartment. Badly furnished but, hey, who’s complaining? Her roommate didn’t arrive until we had all gone back to Bergenfield so I’d never met her. Well, she’s going to meet me now, up close and personal. That’ll be a hoot.

I pressed the buzzer for Connie’s apartment and waited for someone to speak through the intercom. At the same time, an elderly gentleman with gray hair walked by, replete in a metal studded biker outfit, cap, leather jacket, pants, and boots. He looked like a gone-to-seed Marlon Brando from The Wild One. Strangely, there was no sign of a motorcycle anywhere.

“Yes? Who’s there?” the intercom crackled like a transmission from Gemini 8 to mission control. I suppressed the urge to bark out in a gargled tone, “Roger. This is Gemini 8 to Capcom.” Instead, I decided to play it straight.

“Hello. Is Connie there? It’s Shuggie. Can I come up?”

My sister’s voice broke through the clatter like a banshee. “Shuggie?! Wait till I get my hands on you! Come up. Now!” The door buzzed open. I slipped into the building and took the stairs to the third floor. Before I could even knock, Connie opened the door to their apartment, an angry scowl on her face. “Get in here!” She pulled me in roughly by the arm and I was face to face with her roommate Lauren.

“Lauren, this is my brother Shuggie.” Lauren stood there, her mouth agape. I swear she blinked a couple of times like a character on a TV sitcom.

“Your brother? You’re shitting me.”

“I shit you not.”

“Your sister has such a filthy mouth. It’s shameful for a young woman to speak like that,” my grandma declared, shaking her head disdainfully. “I know she’s my grandchild but it’s hard to like her. I think she doesn’t like me.”

“Well, she takes after Dad. And he’s even told me he’s not too fond of you.”

“Yes, Kanako is very much her father’s daughter. But, you my Itsuki-chan, are definitely your mother’s daughter.” She crossed her arms and smiled at me.

Sugar Pie Honey Bunch - Ch. 3

Author:

Audience Rating:

Publication:

Genre:

Character Age:

TG Themes:

TG Elements:

Permission:

“Yes, Mom, Shuggie’s right here, sitting next to me. He’s fine.”

My sister Connie was on the phone with Mom. She kept making faces at me as she tried to calm my mother, who sounded hysterical. Her roommate Lauren pretended she was reading that trashy novel, Valley of the Dolls. I don’t think she was snickering at the author’s insipid writing.

“No, Mom, he’s dressed …uh… normally.” She shot me an icy glare. “Eloping with Bobby?” she coughed up a laugh. “Where would you get that idea, Mom? Grandma? She’s…listen, she probably made that up to make Dad go nuts.”

I placed my head in my hands and tried to bury myself in the recesses of the couch, but the cushions were as hard as blocks of granite. I kept popping back up like a jack-in-the-box.

“Dad wants to speak to him? Okay, hang on.” Placing her hand over the transmitter, she said to me, “Dad. Be careful what you say.” I took the handset from her, cleared my throat, and then tried to speak in as masculine a voice as I could muster.

“Hello, sir. Yes, I’m okay. No, I’m not dressed like a girl!” Unfortunately, I squealed that last part. Trying to sound like Robert Merrill in the role of Figaro in a production of The Barber of Seville, I continued, “I’m sorry I didn’t apprise you of my plan to accompany Robert to his first day of rehearsal, sir. The time just flew by and, well, a telephone wasn’t available. Yes, I’m aware there are millions of payphones in a city the size of New York. Yes, I know I can get change of a dollar at any store.”

Connie ripped the phone from my hand and maintained a calm, even tone that seemed to slow Dad’s inquisition down. “Daddy, Shuggie’s safe and sound and I’ll keep an eye on him. Don’t worry. He can stay here tonight. Lauren won’t mind.” Lauren looked up from her book and shook her head from side to side. “Get some sleep, Dad. You don’t want to miss work two days in a row. Good night.” She hung up.

“I’m not paying for that long distance call,” Lauren declared as she turned back to her reading.

“Shuggie’s paying for it”

“I’m not the one with a job,” I parried.

“Okay, this is the plan. You’ll sleep on the couch. Go brush your teeth and—god, I can’t believe I’m saying this to my own brother—use some cold cream to take off your makeup—”

“I know how to do that!” I interjected.

“And remember to moisturize,” Lauren cackled from behind her book.

“Can I borrow some pajamas? Please?”

“Please do, Connie. I’ll have to tear my eyes out and throw them away if I see your brother in his knickers or, saints preserve us, I see his willie.”

I got up real early the next morning and decided to make nice with my sister and prepared breakfast for her and Lauren. El Pico coffee and toast. For myself, I had Cheerios in milk and sliced the lone banana I found in the kitchen. Potassium helps regulate fluid balance, muscle contractions and nerve signals. Very important for a growing girl like me.

They trudged in from the bedroom they shared, looking more tired than when they shuffled off to sleep last night. They just grumbled, sat down, and started buttering their toast. Connie didn’t even blink when I poured hot java into her cup. Now I know how Mom feels every morning.

“I’m going to see Bobby today and get my luggage and makeup case.”

“Okay, I can give you money for the bus. Get your stuff from Bobby and go down to Port Authority, take the 177 express to Washington Avenue and call Mom. She’ll pick you up.” I nodded and tried not slurp my milk as I usually do. Connie had no idea what my plan for the day was. I was going to get a job so I could go on the summer tour with Bobby. There must be something I could do. I wasn’t one of only two boys in school to take typing and home economics classes for nothing! And I know I typed faster and baked better than Freddy.

After Connie handed me a crisp ten-dollar bill and waved goodbye as she and Lauren went off to work, I made a beeline to their room. I couldn’t show up today wearing the same shmata I had on the day before. I needed to take a look at what Connie had in her closet. She won’t mind if I borrow some nice things. After all, that’s what sisters do, don’t they?

Their bedroom consisted of twin beds, a set of drawers they shared, a small vanity, two chairs, and an armoire. I opened the armoire and rifled through Connie’s dresses. Good thing we were about the same size. Well, she’s a little bustier than I am. And her hips are a little bigger. Other than that, we’re a perfect match!

My choices came down to a pink floral print knee length dress, a brownish tweed skirt suit set with too many pockets, and a blue rayon mini dress with a jewel neckline, puff sleeves and button front. I thought blue was more my color than brown or pink and the mini dress would show off my nicely shaved legs. Done! Now, lingerie. Well, Connie’s bras wouldn’t fit me at all. She’s a B cup at least. Digging through her lingerie drawer, I found a panty girdle that might be a fit. Maidenform! I can see the full-page ad in Vogue now: “Shuggie Brennan’s dreams begin with a Maidenform girdle.” I found the cutest knee-high lace-up white boots with sensible two-inch heels in the armoire. Mine! My knock-off Hermes bucket bag didn’t quite go with my outfit but nobody’s perfect.

A little blush, mascara, Connie’s peach lipstick and voila! I puckered my lips in the bathroom mirror and blushed. How can they not give me a job when I look like this? Mom would be so proud of her beautiful daughter. Dad would have a seizure.

When I strode into 1650 Broadway, looking and feeling years older than 17, the doorman remembered me from the day before and held up his hand.

“Hey, Miss, going up to the rehearsal studio?” I nodded. “These music people don’t usually get started until after 12 noon. Even that’s kinda early. Come back in a couple of hours.” I thanked him and turned to make a graceful exit, feeling a bit like a greenhorn for not knowing. He tipped his cap and smiled. Or was it a leer?

I wandered about for a few minutes on Broadway before The Woolworth’s on the corner of 47th Street drew me in to buy a pack of gum. Doublemint gum to be exact. However, while I was at the register paying for it, a display of lollipops brought a smile to my lips. I’m kind of old for lollipops and the clerk at the register smirked when I added a lemon lollipop to my purchase. I sauntered over to the houseplants department. Sucking on my lollipop, the sweetly sour taste made my face scrunch up in a funny way while I examined a potted aloe vera plant. It would look nice in Mom’s kitchen window. The price tag read a reasonable $2.50.

“That’ll look nice on your desk.” I looked up at a tall man who looked to be in his 40s, wearing an expensive pinstriped Brooks Brothers suit, topped by a dark fedora on his head. I plucked the lollipop out of my mouth. “Pardon?” I blinked at him.

“A little greenery can distract from the gray mundanity of modern office life.”

“Oh, I don’t work in an office. I haven’t even graduated from high school yet.”

“That’s surprising. The way you look. The way you carry yourself. I’d have thought you were a recent college graduate at least.” Blushing, I thanked him. I realized I was holding a rather sticky lollipop in my right hand and a potted aloe vera in my left. My bucket bag was hanging from my right forearm. In short, I looked silly.

“My wife doesn’t understand me.” He stepped closer. I handed the plant to him with a smile. He juggled it for a moment.

“Here, give her this. It’ll brighten up her day. Bye!” I turned and walked very quickly toward the store exit without looking back.

Where could I go to kill a couple of hours? Maybe I could see if Carole and Gerry are in their office. They wouldn’t mind me hanging out with them, would they? I can be very quiet when I want to. It’s just that I rarely if ever want to. My teachers always encourage us to participate in class. I’m just participating in life.

I poked my head through the doorway and saw Carole sitting at the piano, tickling the ivories, and humming some melody. Gerry was on the phone, listening with an annoyed look on his face, puffing on his pipe. Waving to Carole, I quietly sat down on a folding chair, primly keeping my knees together, my bag on my lap.

“Hey, Shuggie, I thought you’d be back in Bergenfield today.”

“I stayed with my sister last night. She and her roommate have an apartment in the Village. Anyway, I’m still planning to go on the tour with Bobby. I think I can get them to hire me.”

“Hire you? To do what?”

“I could be a really good assistant. You know, typing, answering phones, that kind of stuff.”

Carole turned to face me. “They’ve got a road manager for that. Ray Barretto, best road manager in the business. East Coast anyways. He has all the contacts, knows every hotel manager, travel agent, equipment tech, and late-night diner in every city from Boston to Chicago. There are doubts he can actually read and write. Just talks on the phone.” My face fell. Another hope dashed.

“What am I gonna do? My parents won’t let me stay in the city unless I can get a job. They think I’m coming home today. If I could at least spend some time with Bobby before he walks out of my life forever.” I started to tear up.

Gerry had finished his phone call and was re-lighting his pipe. “Tough break, kid. But, you know, these teenage crushes are doomed from the beginning—”

“Why didn’t someone tell me before I met you?” Carole said to the ceiling. She turned to me with a bright expression on her face. “How good is your typing? Are you fast and accurate?”

“I can type 60 words a minute and I’m 93% accurate.”

“That’s better than what I did at James Madison High. Impressive.”

“Especially when you consider I was one of only two…uh…”

“Two what?”

“Juniors. We were juniors. Everyone else in class was a senior.” I would’ve whistled in relief but, thankfully, I can’t whistle. Carole continued.

“Gerry, what do you say we hire Shuggie to be our personal assistant? Jot down lyrics, type them up. You and I both can’t make out my chicken scrawl handwriting sometimes. And she’s a better typist than I am.”

“We could take her salary out of our expense budget. Say $1.50 an hour?”

I jumped out of my chair and hugged Carole. “Thank you! Thank you! I promise I’ll be the best assistant ever!”

“What? No hug for me? You’re working for me too, you know.” I rushed over and hugged Gerry as well. He held onto me a little bit longer than necessary.

“We’ve been working on this song all morning. Take my pad and write down the lyrics as I play. Here’s a pencil. It’s a little rough. I have to sing it in E since it’s written for a guy voice. I’d rather sing it in A. More my range. Gerry’s got a little sore throat. Otherwise, he’d sing it. I’m losing you with all this, aren’t I?” I just nodded, my pencil at the ready. Gerry had come over and stood by the piano, staring at me rather intently. Carole started playing. She told me the title was “Sometime in the Morning.”

“That’s beautiful,” I said when Carole was finished. She smiled.

“How much of that did you get? We’ll run through it a couple more times. I’m still working out the phrasing here and there.”

“Mrs. Winston said I had the best shorthand in our class. But, yeah, I could hear that another time at least.” I giggled. Gerry smiled. You know, he’s a nice-looking man. An older man. But nice-looking all the same. I covered my mouth to stop giggling like a 3-year-old.

“One of the most important duties of a personal assistant is getting coffee. The kitchen’s down the hall to the left.” Gerry pointed with his pipe.

We worked on three songs in all that day, although two of them were incomplete. One, in fact, just had a verse and a chorus. Still, I typed them all up along with carbon copies. Carole only found a handful of typos, so I had to type those over again. But they had plenty of paper and you could reuse the carbons a zillion times. I even suggested they invest in a mimeograph machine. Gerry said they might do that just to sniff the ink that permeated the stencils. “I always volunteered for the ditto squad at school. About 15 minutes in, we’d be weaving around the library office like drunken sailors.”

It was a little after 5 o’clock when Carole and Gerry left for the day, driving back to their house in the well-to-do suburb of West Orange, New Jersey. I sprinted over to 1650 Broadway to see Bobby. I had good news to tell him! Working for Carole and Gerry meant Bobby and I could spend a romantic month together in the Big Apple. There’ll be a teary farewell at the end, but I’ll have these memories forever. Maybe the time together alone can keep me in Bobby’s thoughts while he’s on tour and, hopefully, as long as we may be apart in the future, whatever he decides to do after September.

I was surprised to see the addition of a string section to the band when I quietly snuck into the rehearsal studio. They were in the middle of a duet number between Hank and Honey, with backing vocals by the Honeys, who were doing some coordinated dance moves to one side. Billy Schechter nodded and motioned to me to have a seat next to him on the studio’s old vinyl couch. He mouthed “It Takes Two” and smiled. They were doing a cover of the old Marvin Gaye/Kim Weston song. Bobby spotted me and missed two bars of the song, he was so surprised. Fortunately, no one really noticed, and I looked away quickly. Only to see Billy offering me a Marlboro. I shook my head, putting my hand up. He mouthed “Not your brand?” I nervously smiled in reply as he lit his own smoke.

They rehearsed for another hour or so and then packed up their instruments before scattering. Billy told them they were on their own until tomorrow afternoon. “Don’t do anything I wouldn’t do, kids.” He laughed, patting people on the back as they shuffled out the doors. Once again, the Honeys gave me the side eye as they undulated past. Hank winked at me before feigning an exchange of punches with Billy. They both laughed as they walked out together. Bobby and I were the last to leave the studio. I reached over to take his hand, and, to my surprise, he wrapped his large hand over my slim fingers. He even noticed my peach-colored nail polish.

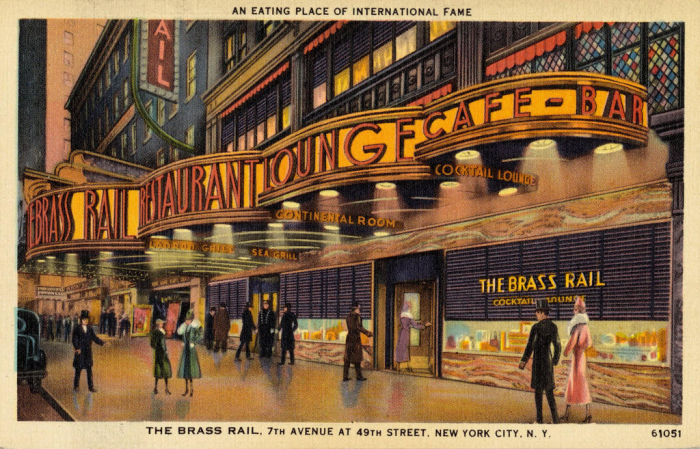

Bobby said we needed to sit down and talk so we walked the two blocks to Tad’s Steakhouse where we could have their famous $1.09 steak dinner. It was a great deal: a T-Bone steak, baked potato, garlic bread, and tossed salad.

“What wine do you recommend, Bobby?”

“Just order the iced tea like you usually do. I’ll just have the water. Listen, Shuggie, I was going to bring your luggage to you tomorrow morning. What are you doing still here?”

“Don’t sound so disappointed. Are you disappointed? Like, really?”

“No, of course not. But there’s no way you can stay with me. I’m crashing at the bass player’s apartment and his wife isn’t too happy about it. They’ve got a baby. I must have woke up 2 or 3 times from the crying last night.”

“Well, I got a job! If I’m working, my dad can’t complain. He doesn’t want me around anyway. I think he’s kind of ashamed of me.”

“What kind of job?”

“I’m Carole and Gerry’s personal assistant. They’re paying me $1.50 an hour!”

“That’s minimum wage, Shuggie. Where are you gonna stay? Your sister’s?”

“I guess so. I was hoping to stay with you but…they’re not putting you up in a hotel?”

“I’m lucky to get per diem. They’re not paying me a real salary until the tour starts. Hey, where’d you get all these…clothes? I mean, in all the time we’ve known each other, sure I’ve seen you dressed up a few times. But never in public. And I looked in your suitcase. Sorry but you didn’t lock it. Where’d you get the outfits?”

“Oh, that. What do you think we do in Home Economics? It’s not that hard to make a dress or two. I told Mrs. Rheingold I was making them for Connie. Connie was in her class three years ago. And the other stuff I bought from thrift stores. Grandma gave me a load of cash for my birthday in May.”

“You made what you’re wearing right now?”

“No, this is my stupid sister’s dress. And boots. And makeup. She won’t even know it’s missing.”

“She will now when you show up wearing it all.”

“I guess I’ve got no other choice.”

“Come on. I’ll drive you downtown. Billy got me a space in the parking garage courtesy of his record label. I don’t even have to pay for it.”

I pressed the doorbell while Bobby carried my luggage in both hands. I heard the thud of footsteps getting louder and then the door opened, offering us a sight that made Bobby drop his dual burden.

Before Connie could speak, I practically shouted, “I got a job! I can stay in the city…with you guys!”

“Well, in that case, I’ll want that $10 back right now.”

“Your sister is a real tightwad,” my grandma sighed.

“Well, she is a business major.”

The front door slammed shut. My parents were home from visiting my convalescing Aunt Brenda. As I got up from the kitchen table where we had been sitting after destroying the Hawaiian pizza, I stifled a yawn.

“We’ll continue the story tomorrow night after dinner, sobo.”

“This is like Days of Our Lives except I can understand more of it.”

Sugar Pie Honey Bunch - Ch. 4

Author:

Audience Rating:

Publication:

Genre:

Character Age:

TG Themes:

TG Elements:

Permission:

The next day in AP Math class, our Vice Principal opened the door halfway and silently beckoned to me. Did they know I was wearing panties underneath my corduroy slacks? I kept my head down as I left the room, his hand surprisingly light on my shoulder.

“You father is here. You need to go with him.” I looked at him and felt myself shiver, my mouth agape. Was I in deep do-do? “He’s in the office waiting for you. He’ll tell you what’s happened.” We were in the administrative office now and I could see my father, in his floor manager smock with his name and title stitched above his heart-side pocket, wearing a serious expression on his face.

As we walked quickly to our car, Dad told me Mom had discovered Grandma slumped over in her chair in the garden, unresponsive, her breathing ragged and shallow. Mom was home since she worked Thursday through Monday at the hospital as a pediatric nurse. They think she had a stroke. I started crying and Dad patted me on the knee. “She’ll be alright. She’s a tough cookie. Don’t fall apart on me, okay?”

Even though my mother worked in a hospital, I hated being inside one. I managed to hold the tears and dread in as we met up with Mom and she took us to the Emergency Room. Almost hidden beneath a web of tubes, an IV bag hanging over her right shoulder, and hooked up to a vital signs monitor, was my sobo. She appeared to be asleep, masking the severity of her condition. But the doctor on duty was optimistic. He surmised it was a minor stroke. Of course, once they got her stabilized, they’d have her undergo a phalanx of tests to get a real prognosis. He smiled comfortingly as he spoke to us. Mom nodded and assured us Doctor Ramsey was just the best.

Several hours later, exhausted from worry and uninterested in food (although Mom assured me the cafeteria fare was quite acceptable), I was ecstatic to see Grandma respond to us, even though her voice was raspy and weak. Mom asked Dad to take me home. She said I needed my eight hours of sleep since I had school tomorrow. I argued the point, but Dad just gently pushed me toward the exit. Grandma had fallen asleep again, but I told her I would see her right after school the next day anyway.

After Dad dropped me off at home and drove back to the hospital, I ran up to my room, performed my nightly ablutions, and put on the extra-large Joe Namath uniform jersey I used as a nightgown facsimile. It came down almost to my knees. Dad had seen me in it numerous times. He did ask me once why I didn’t exchange it for something in my proper size. I told him they were out of medium. He just shook his head and turned back to Johnny Carson on the TV.

Unable to fall asleep, I went to my closet and pulled out Harold, my life-sized stuffed Bengal tiger. I’d had him since I was 5 years old despite Dad having waged a never-ending campaign to have him dumped in the garbage. He said it was disappointing to have a son who was so attached to a little girl’s doll. I know he felt that way from the very first moment he and I set eyes on Harold.

It was the summer of 1954. I was 5 years old and my sister was 8. Dad had driven two hours to have us spend a day in Atlantic City. Back then, it was the fabled site of the Miss America pageant, with a boardwalk, the famous Steel Pier, saltwater taffy, grand hotels with Vegas-like floor shows and concerts (Al Martino was the headliner that weekend!), and amusement park rides for the kiddies.

After a long day in the hot July sun, we were ready to embark upon the two-hour drive back to Bergenfield. Mom and Connie had gone off to find the ladies’ room. Dad and I waited for them next to our car parked outside of Hackney’s Seafood Restaurant where we had just had the catch of the day. I was glad I had refrained from puking my dinner although Connie kept goading me with burping noises. I think I’m allergic to fish. Everyone else in the family loves seafood.

A middle-aged couple, dressed in the summer fashions of the leisure class, approached the restaurant and passed in front of Dad and me. The woman was cradling a life-sized stuffed tiger in her arms, laughing and walking arm-in-arm with her gentleman. She stopped when she saw me.

“Oh, what a lovely little girl!” My father almost jumped. He didn’t manage to say anything but just stood behind me. At first, I didn’t realize she was talking about me. But I was dressed in short shorts, an orange striped t-shirt, and I was still wearing one of Connie’s pink plastic headbands that Mom had deployed to keep my short but unruly hair out of my eyes at dinner. And, heck, I was one cute little tyke.

“Bill, would you be awfully put out if I gave the little prize you won for me to this cute little girl?” she asked the man with her. He shrugged and smiled. “Well, our reservation is for two not three so I guess the least we can do is find a new home for him.”

“Would you like tiger, sweetie?” She placed the over-sized doll in my hands and all I could do was stand it next to me, it was so large.

“Lady, it’s real nice of you but I can’t accept it. Thank you all the same. Shuggie, give the nice lady back the tiger.”

Bill shook his head. “Hey, your little girl here really likes it, don’t you?” I nodded enthusiastically. The lady beamed at me. “Don’t look a gift horse in the mouth, as my Italian grandfather always said. Have a nice evening.” With that, they walked into the restaurant.

Only seconds later, Mom and Connie finally showed up. Of course, Connie immediately ran to hug the tiger. “Connie, he’s mine. A nice lady gave him to me. Daddy, tell Connie!” My father rubbed his face in exasperation and told Connie to hold off. He turned to Mom. “Some rich dame thought Shuggie was a girl. Gave him the tiger. They wouldn’t take no for an answer.” With arms akimbo, Dad bellowed, “Everyone! In the car. We’re going home.”

On the two-hour trip home, Dad kept trying to pawn the tiger off to Connie or, as a last resort, just toss the thing out the window. But I kept my little arms around Harold, as I had already named him, and swore I’d never give him up. Surprisingly, Connie told Dad she didn’t mind me keeping Harold. She was too old to play with stuffed dolls anyway, she said. Dad finally acquiesced but I could tell he was thinking up a plan as he was driving.

I lay in bed, wide awake, the memory of that day still causing my heart to ache. Even 12 years later. Here I am seeking comfort from a stuffed animal my eight-year-old sister didn’t even think twice about spurning. As I brushed the plush fabric with my hand, I couldn’t help but think I might never get the chance to finish telling sobo about my summer adventure. For my own sake, I started to tell Harold what happened after I returned to Connie’s doorstep that evening with Bobby in tow, carrying my luggage. Maybe the words will reach sobo somehow.

Connie wasn’t too happy about me living with her and Lauren in their tiny apartment but, since I could pay my share of the rent now that I had a job, she decided to tolerate my presence. She even smoothed over our parents’ apprehension about my staying in New York for at least the rest of the month (until Bobby goes on tour with Hank & Honey). Of course, she didn’t mention I was presenting as a girl. I could tell her business classes and internship were shaping her into a crack saleswoman. She could sell ice to Eskimos! Bring coal to Newcastle! Send cheese to the moon!

Connie was happy about one thing: not having to lend me anymore of her clothing now that I had secured my luggage. However, she did tell me I could keep the panty girdle I had borrowed. So, it seems my Maidenform dreams would continue.

With these matters settled, my days were a delightful routine of assisting Carole and Gerry from about 10 in the morning until 4 in the afternoon, then rushing over to 1650 Broadway to watch Bobby rehearse until around 7 or 8 in the evening. Bobby and I would catch some dinner in midtown, and he’d drive me back down to the Village afterwards. One night we went to see John Coltrane, Bobby’s favorite sax player, at The Village Vanguard on 7th Avenue and Waverly Place. Although I was sort of bored by what Bobby told me was modal jazz, it suited me fine because I got to spend time with him, and it was a 2-minute drive from Connie’s apartment in Sheridan Square. Bobby only got Sundays off and I suggested we go see a movie but nothing interesting was showing in Manhattan. The only realistic choices were an Elvis movie, The Russians Are Coming, and Khartoum. That was an easy pass. We took a romantic stroll in Central Park instead. Well, I thought of it as romantic. I don’t know what Bobby was thinking. Were we just best buddies? He did hold my hand when the crowd thinned out in certain parts of the park.

That question occupied my mind so much that on Monday morning I hesitantly asked Carole what she would do in my situation. After all, she was a mature and worldly woman who knew enough about the intricacies of love to have written dozens of hit songs chronicling every aspect of the subject. I took the opportunity to broach the topic when Gerry was on the phone waking up someone “on the coast” and Carole was playing back a demo they’d recorded on a Wollensak reel to reel machine.

“I don’t know what’s going on with Bobby and me. Should I just ask him point blank what his feelings are about us? I mean, we’ve been best friends since kindergarten.”

“There’s no doubt about your feelings toward him. Hmm, maybe he just sees you as a little sister. I had crushes on guys in high school and it wasn’t pretty when they acted surprised that I felt that way about them. Gerry and I met in college. Things get more serious when you mature a little.”

“So you think it’s kind of puppy love? But, Carole, he’s my whole world. I think about him day and night. Everyone thinks I ran off with Bobby. Except maybe Bobby.”

“Do you think he’s involved with another girl?”

“He dated this girl Rachel and she’s very pretty. But I didn’t think it was serious. Some of his buddies might have dared him to. Rachel’s very popular.”

Carole switched off the tape machine and sat down at the piano. “Well, my advice is to clear this up with Bobby as soon as possible. It’ll save everyone a lot of grief, especially if he doesn’t feel that way about you. It might hurt real bad for a while but you’ve got your whole life in front of you. Someday you’ll find someone who returns your feelings. I’m sure a beautiful girl like you won’t be lacking for suitors.”

“I’m afraid of what he might say…” I was cut short when Carole started to play. It was a song they’d written for The Shirelles but first released by Maxine Brown, “Oh No Not My Baby.”

“Don’t sell yourself short, Shuggie. There’s a whole world of boys out there. If Bobby isn’t the one, he’s a loser, not you.”

“I know…but I really really love him so so much.” At that moment, Gerry slammed the phone down.

“Kirshner wants us in LA in two weeks. The Monkees need some more songs for their album. Apparently, Boyce and Hart are a little slow on coming up with those Beatles sound-alike tunes they promised.”

Tuesday morning started out really well. Connie and Lauren had left for work over an hour before. I had even scrambled some eggs and fried some sausages for breakfast. I’m getting good at this domestic stuff. And Connie gladly lent me the pinafore apron Mom had gifted her (which she never wore). Visions of sitting at the breakfast table with Bobby, smiling as I poured his coffee, filled my head even as I was humming “Oh No Not My Baby.”

Dressed in the floral print summer frock I had made in Home Ec. class, I stepped out of the building and squinted at the bright morning sun. I was about to go back up and retrieve my sunglasses when I saw Mom getting out of her parked car across the street! When she spotted me, she froze in the middle of the street and a car whizzed by, just missing her by inches. Fortunately, I was wearing my ballet flats that day and ran over to her, grabbed her arm, and dragged her onto the sidewalk.

“Shuggie? You’re…you’re—”

“I know, Mom. I’m sorry we lied to you. It’s…I’m—”

“Beautiful! Just so beautiful. I can’t believe it.”

“Aren’t you mad, Mom?”

“No, Shuggie. How can I be angry at my beautiful little girl?” She hugged me and kissed my forehead. Tears were starting to well up in her eyes. I was crying too. We made quite a scene in the middle of Sheridan Square.

“But how? Does everyone think you’re a girl? Is Bobby in on this? Did he make you do this?”

“We need to sit down and talk, Mom. But, right now, I’ll be late for work if we do that here.”

“I’ll drive you. Just help me with directions. You know I hate driving in the city. It’s so confusing.” We crossed the street again. This time we looked both ways first.

“And I’ll have to speak to this Mrs. King that you’re working for. Does she know? You didn’t tell her?”

“She doesn’t have to know. Mom! She totally thinks I’m a girl. Can’t we just leave well enough alone?”

“No, Shuggie. It’s not right to fool your employer. If she finds out eventually, she won’t be happy you tricked her. You’re legally a boy. And you’re 17.”

What should have been a 15-minute ride turned out to take over half an hour. Uptown traffic even after rush hour is horrible. I would have been better off taking the subway. And immensely better off if my mother weren’t driving me. The whole way up 6th Avenue I tried to dissuade Mom from speaking to Carole. That would end with me getting fired and being forced to return home, my tail between my legs, to endure humiliating recriminations by my father. Dad once threatened to enlist me in the army to make a real man out of me. Can he do that?

“Hi, Carole, Gerry.” My voice was tremulous, betraying the force of emotions behind it. “This is my mother.” She stepped out from behind me and gave them a tiny wave of her hand.

“Hello, Mr. and Mrs. King.” Carole smiled ruefully and Gerry just nodded.

“Please just call me Carole, Mrs. Brennan. I can see where your daughter gets her looks.”

”Thank you, Carole. I’m Eriko. “ She lowered her voice. “Can I speak to you? In private?” She glanced at Gerry, smiling sweetly. Gerry stood up and approached me.

“Come on, Shuggie. Let’s go downstairs and get an egg cream. Your mother and Carole can get acquainted.”

With a desperate, beseeching look on my face, I touched Mom’s arm. “Mom?” She patted my hand. “Go with Mr. King. It’s alright.” Gerry hooked his arm around my shoulder and gently led me out into the hallway. I shot Mom one last imploring look as Carole closed the door to their office.

We walked south, Gerry whistling a tune that sounded familiar, but I couldn’t identify, and me, barely picking up my feet like a condemned woman being led to the electric chair. I would never have envisioned my own mother pulling the switch. My dad, yes, my mom, never.

Four city blocks later, we stopped in front of Howard Johnson’s Restaurant (HoJo to those in the know). “Ever had an egg cream?” Gerry asked me.

“What’s that?”

He laughed. “You really are from Jersey.” Ushering me in, Gerry guided me toward a booth with a window view. “You’re in for a treat if you’ve never had one. I’m from Brooklyn, where they invented it. Like ambrosia. Food of the gods. You’ll see.”

After Gerry ordered, we kind of just stared at each other across the table. I would have whistled, but I can’t, so I just sat there. Gerry looked out the window and at one point actually waved to someone walking by outside. The man stopped for a second, looked at me, and gave Gerry a thumbs up. What was that all about?

The waitress placed two tall fountain glasses filled to the rim with a chocolate-colored liquid. Gerry motioned for me to take a sip. I put the straw in my mouth and siphoned the concoction as Gerry grinned.

“This is good but it’s just a chocolate soda.”

“No, no, no. Egg creams are made with milk, seltzer, and chocolate syrup. Way better than chocolate soda.”

He was right. This was much better. So, we sipped and slurped away. Then, mid-slurp, Gerry turned serious.

“What’s the deal with your mom? Have you escaped from some booby hatch? Or worse even some penitentiary? Did you kill your sister for making everyone call you Shuggie?”

“It’s kind of unusual.” Looking around, I lowered my voice and leaned in across the table. “I’m actually a boy.” Gerry guffawed and then realized I wasn’t kidding.

“Jesus H. Christ.” He lowered his voice. “Are you like, and no offense, but…are you a fagela? No offense.”

“No, I’m not a…a fagela. If you mean what I think you mean. I’m a girl. It’s just I have some extra parts that I don’t want.”

“Does Bobby know?”

Of course. We’ve known each other since I was 5 and he was 6.”

“So, he’s a fagela?”

“No!” I said angrily. “He’s only interested in girls. I’m a special girl.”

“That’s why your mother wanted to speak to Carole discreetly. Well, listen, I’m shocked but I’ve got nothing against however people want to live. He, she, it. Makes no difference to me. Of course, other people might have different opinions.”

“Do you think Carole will fire me?”

“I don’t know. She’s a very liberal person. Voted for Johnson last time. But I don’t think she likes being made a fool of.”

“I wasn’t doing it to trick her. I just needed a way to spend the summer with Bobby. I guess it doesn’t matter anyway. When Mom tells Dad about this, I’m toast.”

He looked at his watch, took a final sip of his egg cream, and stood up. “No sense delaying the inevitable, whatever she decides. Let’s head back.”

As we walked back up Broadway to the office, a black Lincoln Continental, headed in the opposite direction, stopped near us and idled six feet from the curb. The rear side window rolled down and a balding man with a graying beard poked his head out.

“Hey, Gerry!”

“Jerry! I thought you were in LA.”

“Headed to the airport right now. Who’s the young lady?”

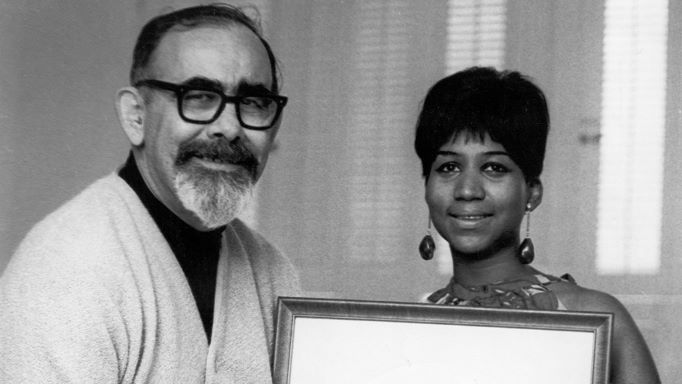

“Jerry Wexler, Atlantic Records macher. Meet my personal assistant, Shuggie.” I smiled reflexively although my glum mood hadn’t lifted and gave him a tiny finger wave.

“Charmed, I’m sure. Listen, before I get a ticket for double parking, I’m signing Aretha Franklin to Atlantic and working on the right kind of material for her talent. Plan to start recording in October or November down in Muscle Shoals. You know I’m really into like blues, soul, gospel stuff. That’s where Aretha should be. She’s not Sarah Vaughan, you dig?”

“Yeah, I hear you.”

“Well, I’d like Aretha to sing about being a ‘natural woman.’ Down home, grits and pig feet, Black church, all that imagery. Just a hunch it could be perfect for her. She could sing the shit out of that phrase. Excuse my French, Shuggie.”

“We’ll work on it. Do a demo and send it out to you. Okay?”

Wexler waved and rolled up his window. The limo drove off. We continued our trek toward the office. “Don’t be all doom and gloom, Shuggie. Another year and you’ll be 18. You could get a sex change operation like Christine Jorgensen. Your parents can’t stop you then.”

“Yeah, well it takes money I don’t have. And no way of making that kind of money anytime soon.”

“It’s tough, Shuggie. I feel bad for you. You make a really beautiful girl too. Shame you were born a boy instead.”

The office door was wide open when we made it back. Carole and Mom were talking quietly. Mom was dabbing at her eyes with a tissue. I was bracing for the bad news.

“We’re back,” Gerry intoned quietly. That left me standing in the doorway, afraid to move, afraid to ask the obvious question. Mom walked over to me after shaking Carole’s hand.

“I have to get to work, Shuggie. I could only take a half-day. Carole and I had a nice chat. She’ll tell you what we decided. And, don’t worry, I won’t tell your father. He doesn’t need to know. Goodbye, sweetie.” She kissed me on the cheek and walked away. I turned toward Carole.

“Sit down, Shuggie. We need to talk.”

Sugar Pie Honey Bunch - Ch. 5

Author:

Audience Rating:

Publication:

Genre:

Character Age:

TG Themes:

TG Elements:

Permission:

I couldn’t stop the tears from flowing as I sat down across from Carole and Gerry. The summer of my dreams was about to end in ignominious humiliation. Through wet eyes I looked down at the dress I was so proud of making by myself in Home Economics class. Mrs. Rheingold told me my sister would be ecstatic that I’d made such a lovely dress for her. She’d probably laugh at me now or, worse, sneer at my “perversity.” And Dad will kill me when he finds out. Would Mom tell him? It wasn’t something I’d bet against.

“Don’t cry, Shuggie,” entreated Carole as she handed me some Kleenex. I remembered to dab, not wipe. But a few sniffles escaped as I tried to collect myself.

“I’m going to ask you a question and I want you to answer me very honestly.”

“Uhh…o-o-kay.”

“Are you doing this just to make Bobby fall in love with you or do you really feel like you’re a girl not a boy?” I was taken aback by Carole’s question. In truth, it was both. But I knew the answer she’d probably prefer. So, I offered “I am a girl! I’ve always known I was a girl. From as early as I can remember. My sister even said so. It’s just I don’t look like a girl…you know…my body…”

“Shuggie, your mother told me that when you were born the doctors weren’t sure whether you were a boy or a girl. They recommended that you be raised as a boy because they kind of threw their hands up.”

“Mom told me that Dad wanted me to be a boy in the worst way. But…but Mom always said she thought I was a girl with…with something extra. That’s not a medical opinion though. Doctor Krantz says I’m just a late bloomer. I could develop any day now…”

“Seventeen is more than a little late for “development.” You need to see some specialists. Child welfare should charge your father with child abuse, really.”

“Dad loves me…in his own way.”

“Be that as it may, Shuggie, your mother urged me to let you keep working for us. And I’m inclined to do just that. She knows this is your last best chance to live out your dream of being a girl, if only for a few weeks or months before you have to go back to school and be a boy again. She loves her younger daughter very much.”

“You mean I’m not fired?”

“No, Gerry and I both think you’re a wonderful and—”

“Unique,” Gerry interjected.

“Uh huh, unique personal assistant. And we’re happy to have you.”

I hugged them both and apologized for making their clothes wet with my tears.

“I have to fix my face. I’m sure I look like a raccoon.”

“Well, a very pretty raccoon in this case,” Gerry said, smiling.

“Sometimes people can be nice. Even in this country.”

My grandmother smiled at me, lying in her hospital bed. They had moved her to a semi-private room. There were two other patients curtained off so that a modicum of privacy was afforded. They gave sobo the bed closest to the window and I sat in the cramped space between it and her bed. I thought she’d been asleep while I picked up the story where we’d left off, the night we ordered pizza. Before she suffered a minor stroke. As I had promised, I came by bus directly after school.

“Go on, shojo. I’m listening.”

Later that day, Gerry and Carole worked on lyrics for the song Jerry Wexler wanted for Aretha Franklin, centered on the phrase “a natural woman.” As Gerry tossed out fragments of lines, I jotted them down. Carole would also throw out ideas but mostly hunched over the piano, humming as she developed a vamp with the song’s opening bars. Around 2 PM, a man and a woman who looked to be in their mid-twenties like Gerry and Carole burst into the room. The man was brandishing a clutch of sheet music and the woman hooted and hollered, waving her arms excitedly.

“Gerry! Carole! We need your help!” Carole pivoted on her chair and Gerry took his pipe out of his mouth, startled out of his lyrical ruminations.

“What’s going on?” Carole asked, holding her hands up like a traffic cop.

The couple turned out to be Cynthia Weil and Barry Mann, another husband/wife songwriting team like Gerry and Carole, who were famous for having written that huge hit for The Righteous Brothers 2 years ago, “You’ve Lost That Loving Feeling.” Barry placed the sheets on the music rack and the three of them huddled around Carole. I silently joined them, keeping myself a foot or two behind.

“Who’s this? I know we’ve been in LA for a while but Louise couldn’t have turned into a teenager overnight,” Barry said, laughing.

“No, Barry, Louise is still only 7. This is our new assistant, Shuggie.” I smiled as Carole ‘formally’ introduced me to Barry and Cynthia. I noticed that Barry winked at Gerry, who quickly turned away and relit his pipe. Cynthia redirected everyone’s attention to the sheet music.

“So, we’re already getting artists who want to cover “(You’re My) Soul and Inspiration” only weeks after it hit the top of the charts. Thing is, we’d like to see it done by a female singer. A medley of “You’ve Lost That Loving Feeling” and “Soul and Inspiration.” Maybe someone like Dusty Springfield or Petula Clark.”

“I thought of reaching out to Peggy Lee,” Barry interjected.

“We changed the lyrics to suit a girl’s point of view and transposed the key from B a half step to C. But neither I nor Cyn can sing in that register,” Barry stated, a smirk on his lips.

“Okay, Barry, we get it. I can’t carry a tune in a bucket. Carole, will you give it a try? We just want to hear what it could sound like in a higher key.”

“I don’t think that would work for me, Cyn. You’d need a real alto voice for this. Maybe even a pure contralto.” I raised my hand timidly. All four looked at me, puzzled.

“I could give it a try. I’m in the range of F3 to F5.”

“That’s pretty low for a girl. I didn’t know you could read music, Shuggie,” Carole exclaimed in mock surprise.

“You never asked. I was in the band at school. I really just got involved because Bobby was so into music, even when we were in elementary school. I play alto clarinet. Rather badly actually,” I added, blushing a crimson tide across my cheeks. When they didn’t comment, I explained, “I could never get my embouchure right. It’s my lips. Maybe something’s wrong with them.”

“Betcha that’s not what Bobby would say,” Gerry said under his breath as Carole drew me closer to the piano so I could read off the sheet music. I exhaled, tried to find somewhere to place my hands and waited for Carole to complete the intro. Then I sang.

There was something close to stunned silence when Carole played the final chord. The three of them exchanged looks. Barry spoke first.

“Wow! I think you’ve got another Little Eva here, Carole.” Turning to me, he asked with incredulity, “You’re not a professional?” I shook my head no. Cynthia grabbed my shoulders. “Oh, god, girl! You’ve got talent! Gerry, why aren’t you producing this little doll?”

Carole stood up from the piano and rescued me from Barry and Cynthia’s clutches. “She’s still in school. And her parents don’t want her in the business at her age.” Gerry blurted out, “And she’s got sort of a medical condition.”

Concerned, Barry and Cynthia both asked “What condition?” Giving them my most bashful expression, I told them, “It’s kind of really personal. I’d rather not talk about it.”

After a few awkward minutes, Barry and Cynthia left. I didn’t realize it when Barry and Cynthia were still in the room but I was shaking, shivering so hard I could barely sit still. Carole asked in a quiet tone, “Do you want to be a singer? You’ve got a nice voice. We can talk to people, you know.”

“No. I don’t want to be a singer. I just want to be a girl. Just a girl.”

Just before they left for the day, Gerry told me they were going to LA at the end of the month and probably stay out there until the end of the year. I nodded and thanked them for giving me the opportunity to spend at least these few weeks in New York with Bobby. After he left on tour with Hank and Honey, I’d have to return home and go back to being a boy. But I’d have these precious memories. Carole hugged me, whispering “Poor Shuggie. You’re so so brave. I don’t think I could cope in your shoes.”

When I saw Bobby at rehearsal that evening, I told him my good news. My mother had revealed my deep, dark secret to Carole but urged her to keep me on as their assistant. Bobby raised his eyebrows at that. Then, unexpectedly, he hugged me. In front of all the other band members who were packing up to leave for the day. “Hey, get a room you two!” Chubby the pianist hollered as he walked out. Hank winked at me and patted Bobby on the back as he led Honey to the exit, arm in arm. The three Hank’s Honeys stood in a line in front of us and serenaded us with Marcie Blaine’s sappy “Bobby’s Girl” from Christmas 1962. Bobby and I jumped apart, embarrassed by the unwanted attention we were attracting.

Bobby said we should celebrate. A feast! Considering our lack of cash, we ended up taking the subway downtown to Chinatown where you could have family style portions for cents on the dollar. Chinatown is a maze of narrow, winding side streets. Every block featured at least three or four restaurants, bake shops, dim sum houses, and curio shops. Bobby seemed to know where we were headed. He held my hand, leading me ultimately to an impressive looking establishment named The Rice Bowl.

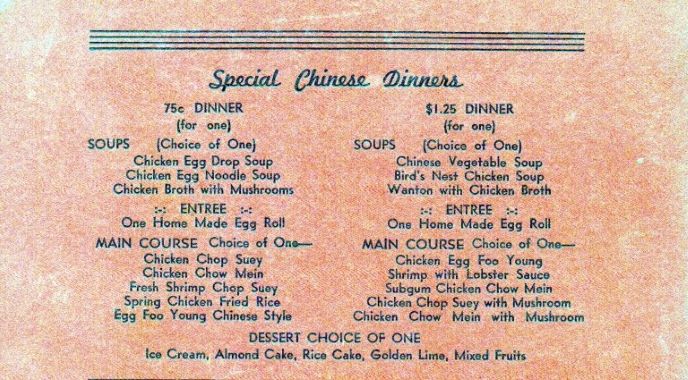

The maître d, dressed in a well-pressed dinner jacket and a clip-on bowtie, eyed Bobby with circumspection. “We prefer gentlemen to wear a jacket and tie in the evening,” he declaimed with a noticeable accent. Bobby was wearing a white button-down shirt, tucked in neatly, and navy dress slacks. The maître d looked me over and, as if reconsidering, waved us in to our table. Surprisingly, for a mid-week evening, the place was packed. He handed us two menus. “Enjoy,” he said and walked imperiously away.

When our waiter appeared, we ordered two $1.25 complete dinners. Bobby had the Shrimp with Lobster Sauce main course. I had the Subgum Chicken Chow Mein. As we ate our sumptuous but frugally priced meal, the irony of me, a half-Asian boy dressed as a girl, having dinner in a Chinatown restaurant with her All-American boyfriend, triggered that earworm of a song from one of my mom’s favorite movie musicals, “Flower Drum Song.” “I Enjoy Being a Girl” played in my head as I watched Bobby devour everything placed in front of him.

“This is really good. You know, I’ve only eaten Chinese food maybe two or three times my whole life.”

“Gee, I was afraid you might be bored by eating here, you probably have this all the time.”