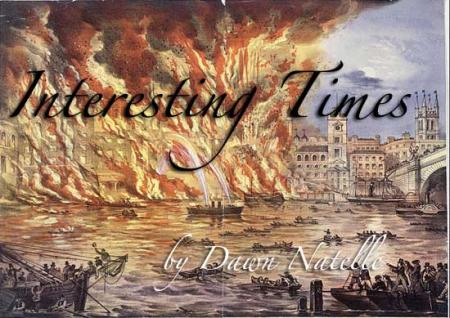

Interesting Times

Author:

Organizational:

Audience Rating:

No story here. This is just the landing page for my next book, which I plan to start posting this weekend or Monday. This book is one I have wanted to write for a long time. It is both a tale of the future, and a tale of the past. The future is the base for the story, after a time travel machine is made allowing people to explore the past. This will occur in this century.

But most of the action in the story will occur in the past, specifically the middle of the 17th century: a period that has long enthralled me. I have about six chapters written, and will post two a week until I get caught up.

Finally, some people might compare this story to Penny Lane’s wonderful Somewhere Else Entirely stories (find and read them if you haven’t). There will be a few similarities, but my story takes place in the real historical earth. That means I have to spend a lot of time on Wikipedia researching the time period to keep things current. It makes writing much harder than my prior books. Also, if I introduce an anachronism into the story, message me.

Chapters One and Two are coming soon, and then single chapters to follow. There will be a test at the end of the term.

Times -- Ch. 01 & 02

Author:

Audience Rating:

Publication:

Genre:

Permission:

May You Live in Interesting Times

Chapter 1

Professor Eleanor Frances Halpenny was nick-named “the Hobbit” by her undergraduate history students. She was named professor emerita 1 at the university when she had passed the age of 80. She had been barely 5 feet tall when she was a young woman: now she was several inches shorter. She was extremely wrinkled. Being 84 does that to one. Her gnome-like appearance was enhanced by a shrill, high-pitched voice.

Douglas Rayles, 28, didn’t mind the old lady. In fact, he nearly idolized her. Nearly 10 years ago he had been majoring in Sociology when he took a first-year history course in his freshman year on campus to meet a degree requirement. The Hobbit was the teacher. At the end of that year he transferred to a history major, and would take five other courses with Professor Halpenny over the next three years. That first course had been listed in the syllabus as covering the history of Stuart England from the death of Queen Elizabeth the First to the beginning of the Hanoverians. In fact the course was a concise history of what the professor called the Glorious Generation. The period from 1642 to 1692 was fifty years, or the lifetime for some people of the time, that included:

- The English Civil Wars

- The beheading of a reigning monarch (Charles I)

- The Commonwealth and Oliver Cromwell

- The Restoration of Charles II

- The Great Plague

- The Great Fire of London

- The abdication/usurpation of the King (James II)

- The Glorious Revolution that brought William III to the throne

Professor Halpenny’s motto for the course was “May you live in interesting times.” Doug was enthralled listening to his professor make those years come alive through her lectures. Most of the other students did not share his enjoyment of the class. Only three or four students were there by choice. The others were merely aiming to get an easy credit in History to meet requirements for their major. In fact, Douglas started out in that group, but fell in love with his wizened old professor and what other students felt was a droning voice, he heard as a song, calling forth the days of yore.

After finishing his undergrad degree in History, Doug went on to take his Masters in the field, and was still in school, working on his Ph.D. in history. He now taught first year students in that same History of Stuart England, trying to make the course as exciting for his students as it had been for him. Professor Halpenny was now his faculty advisor, as she had been in his Masters: one of her few duties as emerita.

But today the two History scholars were in the Physics building, watching a larger crowd from the Religion department. It was recovery date on the second human test of what the Physics department called the Hawking Quantum Chronology Device (HQCD). Basically, it is the first working prototype of the time machine theorized by Steven Hawking. The initial test of the device had been allocated to the Religion department, thanks to a large donation from an alumnus. Five professors had been sent back to spend 24 hours to witness the execution of Christ. Unfortunately, that experiment was a disaster. First, the group arrived five years after the execution, and managed to learn that it had not been Eastertime, but in the fall when Jesus had been executed.

More importantly, every one of the men teleported had changed sex and to a younger age when they landed, and at that time women were not considered important enough to travel alone. Only one of the new women spoke Aramaic, making communication difficult for the English-speakers in the group. They had learned little more than the proper date of the execution before they were pulled back, where they were males again.

The History department was supposed to have the second test, but the Religion department claimed that since their test was a failure, they should be able to go again. This time there were seven sent across, including three female nuns. All seven had studied and learned Palestinian Aramaic, as well as preparing themselves much better about the geography of the area. Four of the original five professors went back: the fifth was so traumatized by his 24 hours as a woman that he refused a second trip, especially since this time a two week visit before and after the crucifixion was planned.

While the Religion people were preparing for their mulligan, History spent several weeks choosing their experiment. Professor Halpenny, although emerita, still carried considerable weight in the department, and her plan to return to 1642 was approved. She asked Douglas to accompany her. It was not an easy decision for the young man to make. For one thing, he would spend 50 years as a woman. But it would be 50 years in the middle of the 17th century, the time period he was studying for his doctoral thesis. Physically he knew he would change as well. He was now 6’4” and he knew he would not a woman of that size. The men from the first Religion experiment said that they had all become young woman of varying heights, but each was much shorter.

Finally, he agreed, and both he and the professor suspended their other tasks at the university. Learning a new language was not necessary: Shakespeare’s plays had been written less than 50 years prior to their arrival time and could still be read today. But they spend a lot of time with a linguistics professor specializing in that period who tutored them on common words and phrases, and differences in pronunciation. He claimed that the spoken word had changed much more over the past 400 years than the written word.

They also spent time studying English money, and getting familiar with the system of pounds, shillings, and pence that was used at the time and approximate values of items. Douglas spent hours learning how to do double entry accounting in the archaic monetary system. There were also penmanship classes, using inkwells and quill pens, and learning to slowly write in the fine penmanship of that era. Douglas, in particular, had to learn to write with a feminine hand. He also was required to take lessons in needlework, weaving, sewing, and other tasks expected of a female lady of the 17th century. He also learned music, and how to sing and play the piano. Finally, Douglas was taught painting by the art department, so that he would have at least the rudiments of art. Professor Halpenny had learned Latin in high school, so she merely had to brush up on it, but had to learn Greek to attain the level an educated man of the 1640s. She also learned to handle a sword, although at her age it was more theory than practice. Luckily she had learned to ride as a young girl, and knew that she would be able to pick it up when she became young again. Douglas did spend some time on horseback learning to ride. Both of them had to learn or brush up on their French, again with a 1640s dialect.

The plan was that they would arrive in late 1642 in southern England near a stage coach route that could take them to London. Professor Halpenny would become William Currie, Earl of Stanstead, and Douglas would become his sister Abigail. They would have documents that attested to their title, and most importantly, money. There were undergraduates in the History department who had been hired to duplicate early Stuart coins, and the time travellers would arrive with a satchel of 5000 pounds sterling in gold. The coinage would technically be counterfeit, but since real gold was used, this was not expected to be a problem.

The satchel was special: something that the Physics department had developed while the Religion mulligan was in progress. It was a type of portal between the time periods. Something placed in the satchel in 1642 could be retrieved seconds later in the 21st century. This would allow the university to continually refurbish the time traveller’s funds, as well as sending messages either direction.

Douglas suddenly sat up. A commotion alerted him that something was happening. He shook the professor’s knee: she had fallen asleep. The recovery of the seven from the time of Christ was taking place, only two hours late.

The people came out of the device in a row, wearing the same clothes they had entered in two weeks before. The nuns were crying softly, the male professors were either sad or angry. The Physics professor who built the device was alarmed immediately and asked what had happened.

The men acted meek, and one of the nuns became the spokesperson. “Everything was wrong,” she said. “The cross was wrong: an X instead of a T. And there were nine executed that day, not three.”

“We waited outside the burial chamber the night he was to rise, and discovered that four of the disciples came in and stole the body,” another nun said. “We followed them, and they buried the body in a different location. He did not rise as we had believed.”

“We trailed most of the other disciples, and found that they met each night that week, but none of them met with the risen Jesus. They just plotted on what to do now that their leader was gone,” the first nun said.

“It means that it was all a lie,” the third nun sobbed. “He was not a savior, just a common rabble-rouser who was killed and then carted away by his disciples, leaving an empty burial chamber. We even looked inside to see if there was a Shroud of Turin, but the room was empty. He was buried in the shroud.”

“It still could be true,” one of the angry professors said. “His soul could have risen. Some of the gospel is misleading … but it could be an allegory, I don’t feel that all is lost.”

It was clear that not all the group agreed. There was a full eight hours of debriefing, and this was the part that Professor Halpenny and Douglas were most interested in. They learned that the transfer had again switched the sex of the people. This time there was a routine that decided the ages and appearance of the transferees, which meant that two of the nuns became men in their 20s, and one of the professors became an older woman in her 30s, thus carrying a little more respect than the young girls that the others became under the defaults. It seemed the machine would make transferees the age of young adults at the end of puberty, unless otherwise conditioned. One of the professors had become a girl of 10, acting as daughter of the older woman, as an experiment. He did not enjoy his two weeks as a child again.

There was not much additional information gained by the history professors, so they left and returned to making plans over the next month while the machine was prepared for their trip. The Religion department tried to get a second mulligan: claiming that they needed to investigate further into the activities after the crucifixion, and before, when they wanted to investigate the miracles that the Gospels claimed Jesus had done. This time they were denied, and the History experiment would be next. The Music department had also put forth a project that would have four male professors go back to 1960 and spend 10 years watching the development of rock music, from the Beatles in the Cavern Club in Liverpool, then to Germany, and finally spending the latter half of the 60s in San Francisco, with a side trip to Woodstock. The Biology department also had a plan to send two female members as sailors on the voyages of the Beagle with Charles Darwin. The additional Religion projects were slotted in after them.

A month later Douglas carried a large trunk, with the satchel sitting on top of it, into the device, and then helped the elderly professor in with him. The door was sealed, and then there were swirling colors. These lasted 20 seconds, much less than the Religion group had experienced. But that group had gone back 2000 years, and this trip was under 400 years.

Suddenly the colors faded and the two found themselves on a dirt road that ran straight as an arrow. They had nailed the landing, coming in about 20 yards from a small wooden bridge that crossed the East Stour River on an old Roman road. Douglas reached down to pull the trunk off to the side of the road, and was amazed by several things.

First, he couldn’t budge the heavy trunk, which seemed to be 150% larger. Then he realized as he leaned forwards there was something surprising on his chest. “I better get that, Abigail,” Professor Halpenny … no, Earl William Currie of Stanstead said. The former diminutive professor was now over a foot taller than Abigail, and well muscled. She lifted the trunk easily. It was all Abigail could do to carry the satchel, full of heavy gold.

“We got the location right,” William said, “and judging from that dust trail down the road, I think we got the time perfect as well. Here comes our ride.”

Stagecoaches were a recent development, having been started 30 years before, but now provided a network across England. The stage pulled up, and the driver and guard seemed tense, looking around. There were no trees within 100 yards, so finally the guard hopped down.

“We have a full coach, milord and milady,” the guard said. “We will move a few to the roof seats to make room for you inside. Rich will shift your trunk up top.” The guard stuck his head in the coach and ordered two men to move out to the roof seats ‘to make room for your betters.’ Then he hefted the trunk onto the baggage area, and helped Abigail, and then William into the coach, where they took seats. The other four inside passengers were two couples, one apparently a merchant and wife, and the other a well-dressed couple who spent the next few minutes comparing the quality of their clothes with the newcomers, to determine who might have the higher social standing.

Eventually it turned out that they were a Baron and his Lady, and when they discovered that William was an Earl, they bowed politely. They initially referred to Abigail as Countess2, until it was explained that the two were brother and sister, and not a married couple.

A half hour later the stage stopped in a wooded copse. There was a tree in the roadway, and seconds later a band of five men and a boy surrounded the rear of the stage, preventing it from reversing direction.

“Out. Out everyone,” the leader of the band shouted.

This was bad. Once the bandits discovered what was in the satchel, they would take it. The gold was not important: the important thing was the satchel itself: the pair’s link with the future. Abigail thought quickly, and handed the satchel to William. She backed out of the coach, but as she did so she retrieved her secret weapon: a seven-inch dagger that she had the costume designer sew into a sheath nestled between her breasts. She may have to be a girl for the next 50 years, but she had vowed she would not be a defenseless one. William saw her draw the weapon, and smiled as she concealed it in the fringe of her blouse sleeve.

William had his sword of course, but the surprise of the dagger could be just what he needed. Before he left the stage he unclasped the top of the satchel. When he got out he dropped the satchel, and the top flew open, with a few gold coins popping out.

This caused the head bandit to drop from his horse, drawn by the massive amount of gold. He kneeled and ran his fingers through the money: “Lookee here boys. We have treasure here.”

That was when Abigail stepped forward, drawing her dagger. The man didn’t even look up until the dagger was at his throat and slicing into it. The bandit fell, and William drew his sword before either of the others could react.

One man on horseback held a primitive pistol and was about to aim it at William, so Abigail threw her dagger, aiming for his arm but hitting his chest. The man fell from his horse, and the gun bounded away. William took on the other two men in a sword fight, and Abigail grabbed onto the boy, who seemed to be about eight years old.

Rich, the guard got into the action a few seconds later, and with two swords against two, the bandits quickly were vanquished. The guard killed his, and when the man facing William threw down his sword to surrender, the guard also killed that man. He would have killed the boy as well, but Abigail stepped in front of the lad.

They surveyed the carnage. The guard had killed two. One had ridden away at the start of the fight, when he saw the lifeless leader with a bloody smile across his throat. The gunman was dead too: Abigail’s dagger had gone into his heart as well as nicking his arm. The boy was shivering in Abigail’s arms.

William gathered up his coins, giving one to the guard for his assistance. The dead men were trussed to the horses they had ridden in on. The guard collected the dropped firearm, and seemed pleased that he would have it for future battles.

“We are only five minutes to the next stage station. Then it will be another hour into London,” James, the driver said. “We will get rid of that baggage at the next station. Your lady killed two, so she gets two of the horses. The best two, I think. Rich here killed the other two, so he gets the last two. Shame we lost the fifth, but after seeing four of his mates mowed down, that fellow might be looking for another line of work. Now what are we to do with that half-sized bandit?”

“He will go with us,” Abigail announced. “He is small. He can lay on the floor of the coach.”

No one was going to argue with the young girl who had just casually killed two men, and was wiping the blood from her dagger onto the hat the bandit leader had been wearing. “Anyone want this?” she asked, waving the hat. “It’s a bit dirty now.”

“I’ll take it,” one of the topside riders said, and she flung it up to the top of the coach. The bandits hadn’t even gotten them down from their seats.

The dead men’s horses, with their noxious burden, were hitched to the rear of the stage, and the party was soon underway, although at a walking pace, which meant the normal 10 minute ride to the next stage station would take about a half hour. Inside the once-quiet riders seemed to have bonded over their experience, and were quite chatty with each other. The men now sat on one side of the coach, facing the rear, and the women were facing the front. The boy, bound hand and foot, lay on the floor of the coach.

“I’m so glad we picked you up,” the merchant said to William. “I don’t have nearly as much money as you do,” he gestured at the satchel, “but what I have in my money belt is nearly all I have. We are headed to the cattle market to buy stock for my shop in Maidstone. If I was robbed I would have been unable to buy anything, and soon my store would be empty.”

“This is very important to me too,” William patted the satchel. “We are returning from France, and I hope to be able to buy us a home in London. I am an Earl, but currently have no estates.”

“Ah,” Baron Stephen of Downsland said, “estates can be more trouble than they are worth. First we have the King’s men coming to collect taxes, and then the Parliament men come around, and want the same taxes. More and more each time, and often several times in the year. Much of our savings are gone, and we have to squeeze the people. And they don’t have money either. I wish they would realize that these wars they keep fighting cost money, and we have no more money to give.”

“You come to London too, then?” William asked.

“Yes. My lands are right at the edge of the territories, with Parliament holding lands to the east, and the King the lands to the west. I honor the King, but staying up there left me exposed to both. Here at least there will be only one set of taxes to pay, if my steward can send me money before the Stuarts get to it.”

The three men smiled at the baron’s quip. “The one good thing is that the troubles have made rents in London much cheaper. I rented a house for a third the price of last year. Usually we only come down for the season, but this year I think we will stay until the troubles are over. You should be able to buy cheaply as well.”

“The season?” William queried.

“The fall season,” the baron replied. “We have many friends in the city and during the season we all have fetes and feasts. Of course as an Earl you will be travelling in a much higher circle. But Mary and I would be quite honored to have you and the Countess, I mean your sister, attend the affair we will be hosting.”

“We would hope to come,” William said.

“That would be so gracious of you, milord,” the baron said. “For one thing, no one will believe my tale of what just happened today without collaboration.”

“Tell me more of the troubles,” William said. After all, one of the goals of the project was to find out what people thought about things. When written down, accounts often lost this human element of the story. Here he had a chance to get the impressions from two men at different social positions. They chatted all the way to the stage station, and then again all the way into London.

Meanwhile Abigail had chatted with the women. She hadn’t flowed into conversation ad quickly as her ‘brother’, primarily because the others were in complete awe of her. She had killed two bandits alone.

“You are too brave,” the merchant’s wife finally said. “To think to draw your dagger, and then to use it so quickly. Have you ever done that before?”

“No,” Abigail said. “I had practiced throwing it, but never had used one on a living person. It surprised me how easily it went into the man’s throat. The throw was not meant to kill, but the man was turning to fire his pistol at us, and it only nicked his arm. Unfortunately his chest was where it ended up.”

“You are still so calm,” the Baroness Norah said. “I am still shaking, and did nothing more than stand there and wonder if all my jewels were to be taken. And possibly more. It is said that these bandits sometimes made free with women after killing their men.”

“Oh God, no,” the merchant wife gasped. “I never thought of that. Oh my. I could never … Oh my.” Abigail looked at the woman, who apparently thought rape was the worse part of the scenario, ignoring the fact that her husband would have been killed first. “We owe more to you than we thought,” she finally said to Abigail when she was coherent again.

“Eventually the women put their ordeal behind them and spoke of other things. The women were most interested in knowing what the Paris fashions were like, and wondered what they might import for their gowns for the ‘season,’ which was a big thing for the baroness. The other woman said that the ‘season’ in Maidstone was much less ornate, although her husband’s business would double, which was why he was coming to London to buy cattle. They would not initially enter the city, but stop a stage or two outside where the cattle markets were. After they bought their stock, they would hire drovers to take it to Maidstone, and the couple would continue into the city to buy goods from London merchants, and take them home by coach, arriving a day or two before their cattle would arrive.

At the stage station, the stationmaster was out immediately to accuse the driver of being late. Then when he saw the extra horses and their cargo he stopped. Then there was a recounting of the event.

During the hour that they were delayed at the station, one coach went in the other direction and shortly thereafter another coach came on the London-bound run. It was not full, so the merchant and his wife moved to it while the baron and baroness decided to dine in the station with Abigail while William spoke with the stationmaster. Two of the outside passengers also moved to the other coach.

William came in and tossed fourteen pounds on the table in front of his sister. “I sold your horses to the stationmaster. No sense taking them all the way into the city. They wouldn’t be able to stay hitched to our coach: it would slow it down too much. If we need horses in London we can buy there. Abigail gathered up the coin. Why had William not just put it into the satchel? Then it hit her. He wanted the money split up, so if they lost the satchel they would have something.

William got the kitchen to make him a roll containing a thick slice of cheddar and as much beef. So much for the myth of the Earl of Sandwich inventing this in the 1700s. Perhaps when they returned to the present, people would be referring to it as a Stanstead.

Without the merchants the boy had a seat, although his hands and feet were still bound. He sat next to Abigail, who had gotten him a “Stanstead” and was tearing off bite-size morsels to feed him as they rode towards the big city, to the amusement of the baroness. The boy was ravenous, and ate the entire sandwich in only a few minutes, drinking from a water flask Abigail carried. He then curled up beside his benefactor and fell asleep.

“What will you do with him?” the baroness asked. “He could hang as a member of the gang.”

“He is not a criminal: only a boy,” Abigail retorted. “We will find him a place in our staff, if he wishes it.”

“He certainly will wish it, if you keep feeding him so well,” the baroness said. “That food was more than most of my husband’s tenants get in two days.”

“It was probably more than two days since he last ate,” Abigail said. “Those men didn’t seem well fed. I suspect the boy got the slim pickings that were left after they ate.”

“The women chatted alone for the next few hours as dusk fell and they approached London. The boy woke up, and found that he was no longer bound. “Me hands are free,” he said in awe.

“And your feet,” Abigail said softly. “Being bound was making it hard for you to sleep well. I trust you not to run away. You could if you wish. I will not keep you as a slave, but a servant. Will you serve me?”

The boy slid to the floor of the coach and grasped the lowest hem on Abigail’s dress. “Milady, I’ll serve you all the rest of my life. You saved me. Those men did … they did ‘orrible things to me at nights. I were glad to see you and the guard kill ‘em.”

“Rise up young man. Have you a name?”

“I is Joe,” the boy said, standing. “Hank, the one you slit his throat, says I must have another name, but I dunno what it is.”

“I will give you my name as a surname,” Abigail said. “I am named Abigail Currie. Your new name will be Joseph Curryman.”

“That’s a lot, milady, for one as small as I is. Per’aps I could stay as just Joe till I gets that big one into my head.” He did seem to show pride on his face that he now had as many names as most common people.

“Milady,” he confessed. “I kin tell you where Hank and the others stashed their takin’s.”

“What of the one who ran away?” Abigail said. “Surely he will go and move the stolen goods.”

“’e don’t know, does ‘e?” Joe said. “’e was just picked up by the boys earlier that day, new to the gang, yer see. ‘e never did a night with us in the cave. But I knows where it is. Leastwise, if you kin get me back to that there place. I’ll lead you and your brother to the booty. There is a lot. Not much money but lots of jewels and stuff. Hank takes that to the city during fair week, where there’s pawners from away what’ll buy suspicious jewels cheap.”

William had been listening to the dialog between his sister and her new servant. “We will go for a ride in a day or two, youngster,” he said. “You do ride?” The boy nodded. “How many men will we need to carry away the booty, as you call it?”

The boy looked confused, and then started calculating. “I don’t knows no numbers, milord. But there would be this many bags the size of that ‘un.” He pointed to the satchel and then started rising fingers as he visualized the booty hoard. He stopped with seven fingers up. “That many ‘ll do it, I reckons.”

Chapter Two

The stage arrived in London late, and the final stop was at an inn the baroness said was not suitable for people of their place in society. So as soon as the coach stopped, Abigail sent Joe out to find another place Norah recommended, and reserve a room for them. The baron and wife took a cabriolet3 to their rented home after making sure that William had the address for a future meeting.

Abigail’s trunk was a problem. It was too large to fit in a cabriolet, so William arranged to store it at the stage yard after Abigail got a nightdress out and placed it in her handbag. He also arranged for a driver and a local carriage for the following morning. James, the coach driver, agreed to take the commission, and promised to wait at their inn at 6 a.m.

The cab got them to the inn in good time, and Joe was waiting out front. “They’s got a room as is fit for an Earl, they says,” he reported, “and one more for milady. I hope that’s okay.”

“I’m sure it will be,” Abigail said. “I’m guessing you are hungry again. Do you think we should eat? It will be an early morning for us.”

“I could eat,” the boy said with a huge grin. “I can’t reckon ever saying no to a good nosh. Or even one not so good as that you offer.”

Abigail giggled, and then stopped as she realized that she had giggled. She led the boy into the inn, and realized that he was closer to her height than she was to William’s. The inn had no common bar, so the main room was nearly empty. The kitchen was closed, so William merely asked for buns with cheddar and roast beef slices. He also asked for more of the same in the morning, when they would be leaving quite early. The innkeeper looked askance at that, but smiled again when William said he would pay in advance. Abigail didn’t see what the charges were, but William paid with shillings and not pounds. She would have been happy paying pennies at the ‘low class’ coaching inn but realized that people of her status must keep up appearances.

In her room, Abigail struggled to get out of her dress, which was somewhat soiled. She would have to wear it again in the morning. She learned why women of these times had maids … she was completely stymied in getting the garment off.

There was a tap on the door while she was struggling, and William slipped in. He saw the problems that she was having, and moved quickly to help. “But you are a man now,” Abigail hissed as he unbuttoned the back of the gown.

“You have nothing I haven’t seen in a mirror every morning for over 70 years,” he said. “Although not as much, I’ll warrant.” He added as he lifted the gown from her and laid it on the bed, revealing her in her undergarments.

“I thought as much,” Abigail said as she looked down on her breasts laying atop her corset. “Those clowns in the Physics department changed my pattern. I was supposed to be a C cup. I’m only 15 here, dammit. “But these are at least DDs.”

“I’ll say,” William said, staring at her barely covered breasts.

“And if you will just loosen the ties on my corset, then get the hell back to your own room. Or the washroom. The parts that you haven’t had for over 70 years are starting to alarm me.”

William looked down at his first ever erection, and did as Abigail said. He hurried from the room, muttering ‘my sister. She’s my sister’ as he did. With the big man gone, Abigail pulled off the corset and put on the nightdress. Why was she panting heavily, she wondered. Was it from being undressed by a tall, strong man? One that was able to tent his trousers in such an interesting way?

The next morning the boots4 rapped on the door at 5:30 to wake them, and William came in her room a few minutes later. Abigail had just managed to get back from the washroom where she did her morning ablutions. William helped her into her corset, and then the gown from yesterday.

They went down to the dining room, where the cook had the requested rolls ready. Joe darted out the door and then popped back in, announcing “Coach’s here. Same driver as yesterday,” he said. “Looks like yer trunk is on top.”

They ate their breakfast in the carriage. Joe reveled in having his third meal in 24-hours, more food than he usually got in a week. He had prayed for the first time in years last night, thanking the Lord for having milady find him, and take him in. He also prayed his new lord and lady.

James, the driver, recognized Abigail’s description of the place she wanted to go. In her research back at the university Douglas had learned of a certain Duke who had become insolvent at the time they were now in. His butler, who had served the Duke’s father for 25 years, and the new duke for nearly 15, had committed suicide the very morning they were now in.

There was a B plan if they didn’t meet the butler, but things would work out much better if they found him before he jumped. Even more so for the man. James stopped at the spot Abigail indicated, and the three of them got out. Joe ran ahead with specific instructions to delay the man, if he could be found, while the time travellers walked along the river, looking down below to see if there might be a body in the weeds. James stayed in the carriage, and moved it along every few hundred yards that the couple walked.

It was a foggy morning, and it was hard to see down to the river’s edge, but Abigail peered hard to see if she could spot anything. Eventually William nudged her, and she could see Joe up ahead, talking to a man of about 50.

“Good day sir,” William said. Abigail noticed that the man was sweating profusely in spite of the cool damp, and seemed to be nervous, although Joe was chatting animatedly with him. The man’s clothing was that of a high-class servant, but worn and tattered looking.

“The river is interesting in the morning,” William said. “It is our first day in London, after spending some time in France, and before that in India, where our parents made their fortune, but lost their lives to the disease. We returned, travelling through France, with several months in Paris. Now we are here to see a cousin, the Duke of Spritzland.”

The man jumped as William mentioned their destination. “I know that house,” he said softly. “I am … I was … the butler there. But I fear you are out of luck. Today the house is being foreclosed on. The young Duke, unfortunately has a habit of spending time at the gambling tables. He inherited a tidy fortune from the old Duke, but his ways at the tables were not lucky. Five years ago today he mortgaged the house and his estates in Sussex. Other estates have been sold since, and by noon today he will be landless and homeless. That is why I am no longer the butler.”

“It is nearly five hours until noon,” Abigail said. “Surely we can do something?”

“Unless you have 3000 pounds handy, no,” the butler said. He looked startled as William smiled. They had walked back to the carriage, and the man stood outside as William climbed in: “Tell me, are your wages paid up at the house of Spritzland.”

The butler laughed. “No. None of us have been paid for two years. Several have left for other positions. I have not been paid for three years. The house owes money to all the trades, and the Duke has sold or pawned almost all the furnishings. There is no food at all in the house. We have been living on oatmeal from the stables for the past month, and today the cook said that was gone.”

“What was your salary there?” William asked. “Please get in the carriage with us. We will take you home.”

“I was to be paid £15 a quarter,” explained Hockings, as he said his name was.

“Sixty a year, three years … here is £200. I am in need of a butler. Would you serve me?”

“Yes milord,” Hockings said in amazement. “At what house?”

“The same one you have lived in for 40 years. I plan to buy it from my cousin. He and his family will continue to live there, but if I own it, and all the fixtures, then he will no longer be able to gamble it away. Now, if the larder is empty, we should stop at some shops as they open so that the staff and family can break their fast.”

It took a few minutes for Hockings to realize that salvation was at hand, and he directed James to a commercial district that was just starting to open up. No super markets in this time period, Abigail learned. You needed to go to a different shop for almost every product. One stop for milk, cheese and butter, another for bread. Meats were all in one location, staples in another. One more shop for root vegetables.

In almost every shop the owners nearly chased Hockings out of the store, until William showed them coin, and said that he was the one purchasing. He also told the shopkeepers that if they appeared at the Duke’s residence in the afternoon with evidence of the debt owed, then all arrears would be cleared. The only condition was that the Duke sell his home to William.

They arrived at the beautiful large mansion at about 7:30 in the morning, and found the place nearly deserted. Hockings ushered William into the Duke’s office, while the other three carried goods down to the kitchens.

“Who are you?” snapped the Duke as William entered. He was standing behind a small, cheap table. There were no chairs or stools in the room. “The mortgage is not due until noon. Are you that eager to put my household on the street?”

“I am not from the people you are dealing with in that matter,” William said, pulling a letter out of his satchel without revealing the other contents. “I am your cousin, William Currie of Stanstead, and have arrived with my sister Abigail. By chance we met your man Hockings, and heard of your dilemma.”

“Looking for a bed and meals, I suspect,” the Duke said bitterly. “Well I’m afraid that it is too late for either.”

“Perhaps not,” William said, grabbing a fistful of pound coins from the satchel, and setting them on the table, which held a large document that the Earl recognized as a mortgage promissory note. “May I?”

“Yes, certainly,” the Duke said, mesmerized by the sight of gold.

“This says you need to pay £3215 by noon today,” William read from the mortgage. “I think we can cover that. However, this is not a gift. I mean to buy the house and the Sussex estates with that amount.”

“So we are still out on the streets,” the Duke muttered. “I see no difference.”

“The difference is that you are family, and will continue to live in the house. I wish I could allow it to appear in your name, but then people would continue to come after it to cover gambling debts. So it will have to become known that I own the house and lands. I don’t seek your title. That will remain with you. But I will own the house, and run the house. Everything in the house will belong to me, even the clothes you wear. The servants will report to me, not you. I will allow you £10 a week for your gambling, no more.”

“Ten pounds?” the Duke roared. “That is nothing. I need at least £200 a night.”

“And that is why you are on the verge of being the first Duke of England to go to a workhouse,” William said. “That is my offer. Do you accept?”

The Duke only hesitated for a few moments, and then signed the bill of sale, with Hockings, and a woman named Bentley, apparently the housekeeper, witnessing it. She had arrived with food, although the cooked buns were carried on a slab of wood, all the actual platters having been sold or pawned.

“I was told that there was no food,” the Duke said, as he and William each took a roll.

“The larder is restocked,” Bentley said. “The cook is currently working on a dinner for tonight like we haven’t seen in months.”

The servants left, and the nobles swept the crumbs from the table, and started to work making stacks of one pound coins 50 high, eventually making 64 piles, with another smaller pile of 15 coins. It was shortly after they finished counting and recounting, that the moneylender who held the mortgage arrived. He was amazed to see the money sitting on the table. After the shock wore off, he smiled.

“I will gladly take cash for the house,” he said. “The estates in the country are worth more, but London houses are selling slow with all the troubles, and cash will actually suit me better.”

The man counted the coin twice, and at the end insisted that another £200 was due because it was now 12:45, and the mortgage specified that the payment be made by noon. He called for a penalty.

“The money was sitting on that table at 10 a.m.,” William said, his voice rising. “If anyone is to pay a penalty, it is you for making us wait while you dithered about the count. Anyone with the least bit of math skills could assess the total in two minutes, and you took over an hour. I think you owe us £200 for trying to extract more than your due.” William stuck out his hand.

“No, no, that is fine. I will waive the penalty,” the moneylender said. “Now let us sign the mortgage to settle it.” This time it was Hockings and William who witnessed the transaction, and the moneylender left.

“Sir,” Hocking addressed William, and not the Duke. “There are several tradespeople here to see you.”

“Ah yes,” William said. “Send them in according to how long they have been waiting.” You need not remain for this, milord,” William dismissed the Duke, who headed off to the kitchens to see what was going on down there.

“Before you call them in, Hockings,” William asked. “Do any of the staff read, write, and do sums?”

“I do, sir, and Bentley, of course. The cook has some expertise with money, but I don’t think she can write. Oh, Kensing in the stables is educated. I’m not sure why he is still with us.”

“Good. I want Kensing, and James, the driver who has our carriage, to go buy some horses and a wagon. Am I right in assuming that we have none?” The butler nodded. “Have the head of the stables go with them. Also …”

“Sorry to interrupt, but Jones, the stablemaster, left us eight weeks ago. He said he wouldn’t work at a stables that had no horses after the master … the old master … pawned them off.”

“Okay. But I also want another man, someone with some muscle. And who is the senior maid after Bentley?”

“That would be Winthrope,” Hockings said.

“Excellent. Have them come in to see me as soon as you can arrange it. And send Joe as well. They may need a runner.”

Williams got through the first three merchants before the staff he requested were ushered in. The merchants had been easy to deal with. They all came in with bills and accounts, expecting to have to argue just to get a portion of their money. The amount they were willing to pay as a discount for immediate payment varied from 20 percent to 50 percent. To their surprise, William merely scanned the accounts to verify that they seemed accurate, and then paid 100 percent for the arrears, rounding up to the nearest pound. When William told them that future accounts would be paid in full at the end of the month, they were all smiles and willing to do business with the house again.

When the staff popped in, William quickly explained that he wanted James to go to his masters and purchase four carriage horses, preferably the ones that he had rented for the day, and the carriage and tack. He also needed two more common horses and a work wagon and tack.

“Hmm, let’s see,” the driver said. “The boss will probably want £250 for that carriage. I know he paid £200 for it, and he’s rented it out several times. Carriage horses will probably go for £12.50 each. The troubles have driven up the price of horses something terrible. A decent wagon will cost you £50: the troubles again. Common horses will be £10 each. So you are going to be looking at £370.”

William was impressed at how quickly the man had toted up the prices. “Next question. There is a vacancy for stable master here. Are you interested in the job?”

“I might be. What’s the pay?”

“I can offer 13 pounds a quarter,” William said.

“I get 15 now,” James said. “But getting held up by bandits is a not an attractive part of the job. And next time there may not be people in the coach as good as you and your sister at quelling them.”

“The job includes room and board. Are you married? Children?”

“The wife takes in laundry. This kids are grown and have families of their own.”

“We might be able to find a position for your wife here. I am short staffed right now.”

“I’m your man then,” James said. “When do I start?”

“Right now, if your current boss doesn’t need notice.” William took £400 from the satchel, and was surprised to see that it was full again in spite of nearly £4000 being taken out for the mortgage and payments to the suppliers.

He reached in and took out another £500 and handed it to Kensing. I want you to take the wagon and team that James will buy you, and head out and try to find some furniture for this place. Winthrope is with you because she will know what is needed. Beds are of importance. I’ve slept on a hard floor before, but don’t relish doing it again. A wardrobe for my sister. Whatever is missing from the rooms of the Duke, Duchess, and their daughter. Cleaning supplies if we need them. Everything that we need to get this house livable again. Have things sent on if the vendors can, otherwise pile them on the wagon. Send Joe back if you need more money. If you see anything that is from the house, I want it. Buy it if it is reasonable, but make note and let me know if it is not. I may overpay if it is an important part of the house’s heritage.”

After they left, there were eight more vendors to settle up with, and again all left with large smiles and full pockets.

“That was the last,” Hocking said after leading a merchant to the door.

“Good. I guess the next step will be to have a staff meeting. I would like to have all the staff get together so I can address them. Where would be a good place?”

“The Great Hall,” Hocking said. “It is where banquets and dances were held by the old Duke. It is not much used any longer. But I’m not sure this is a good time, sir. The kitchen will be well underway for dinner and cannot just leave pots and roasts.”

“Of course,” William said, slapping his head. “And I just sent a bunch of staff off an hour ago. We will do the meeting after supper.”

“That would be better, sir. There is still much to do in the kitchens then, but it is washing up, and that can wait, while cookery cannot.”

Just then a footman appeared. “Sir, milord, there is a wagon out front with furniture on it. Do we have an order coming in?”

“Many orders,” William said. “Bring it in.” That first load contained a fine dining room table, as well as another table that was immediately taken to the kitchen, where the staff cheered to have a work surface back to prepare on. William noticed that some of the undercooks were sitting on the floor, with mixing bowls between their legs. The Duke had totally gutted the place.

The good table went into the dining room, and there were four chairs, as well as two long benches for the sides. One four-poster bed was brought in, and placed in the room that Bentley said would be Abigail’s. The next wagon to appear was from a mercer, and contained curtains, towels, linens and bedclothes. It also included several mattresses.

The last wagon was driven by Kensing, with Winthrope sitting beside him. It contained a beautiful desk for the office, which apparently had sat there for 60 years before the Duke sold it. There was also another four-poster bed, so William would not be sleeping on the ground, and the final piece of furniture was a wardrobe that Winthrope thought would work in Abigail’s room.

“Good job all,” William told them. “I want you to go out again tomorrow, and do it all over again. We have a lot of money to spend to get this house looking reasonable again.

- Emerita is the feminine of Emeritus, the term for a professor who has passed the normal retirement age, but maintains a connection with the university, often a reduced teaching schedule.

- Countess is the proper term for the female Count or Earl. There is no Earless, which is a term for a person without ears.

- A cabriolet was a small, light conveyance pulled by a single horse and holding two people (and a driver). The present term ‘cab’ comes from this term.

- The ‘boots’ was a servant, usually a young boy, who was responsible for getting up early in the morning to take any boots that had been left outside of the doors of a room, and polish them, if leather, or brush them clean for other types. The clean boots were to be back at the doors of the patron when he woke up. In the case of a hotel, or when visiting another house, a visitor would drop four pence or so into the toe of one boot as a tip.

Times -- Ch. 03

Author:

Audience Rating:

Publication:

Genre:

Permission:

May You Live in Interesting Times

Chapter 3

Abigail carried the goods she and William had picked up on the way to the Duke’s house, along with James the carriage driver, and Joe. They were met by a woman a few years older than Hockings, and he introduced her as Bentley, the head housekeeper. The woman grabbed the bags Hockings carried, and led the others to the kitchens, while the two men went to the Duke’s office. They found most of the staff in the kitchen, idly standing around.

“Have none of you anything to do?” Bentley asked angrily.

“Not really,” a man’s voice from the back replied. “We’re going to be on the street by noon, and hungrier than we are now.

“We have brought some food,” Abigail said. She looked around and could see no place to put the bags she carried. She set them on the floor. “We have rolls in these bags, and the bags that James, my driver, carries have some cold cooked beef and cheese. Perhaps we can all make a bun to break our fast and then have a little chat.”

The meat and cheese were put onto a small, rickety table, the only one in the kitchen. A woman Abigail assumed was the cook cut slices off the beef, and another woman cut slices off the block of cheddar. A third woman sliced the rolls after moving the bag to her feet. The staff formed a line and politely moved along, each getting a bun of meat and cheese at the end. Soon everyone was munching happily: breakfast in the past weeks had been weak oatmeal gruel, and there was none at all yesterday or today. Eyes were wide as they spied the meats and other foods that had been brought down to the kitchen. Abigail sent Bentley up to the office with buns for the Duke and William.

“You are all probably wondering who I am,” Abigail said as the staff ate. “My name is Abigail Currie, and my brother, William Currie, Earl of Stanstead is currently up with our cousin, your master, trying to save the house. If all goes well, we will be in possession of the house after noon, and will want to keep most of you, if not all, to stay on as staff. So when you are finished eating I want you all to go to your work. Your new master will want to inspect the property, and how well it looks will determine whether or not he wishes to keep you on. The kitchen staff should concentrate on cooking dinner. There is a ham in one of these bundles, so there will be meat for dinner today. Not just for the main dining room, but for the downstairs table as well. Although I don’t see a table here at the present time.

Bentley returned carrying her wooden platter. “The Duchess and her daughter will not have eaten yet,” Abigail noted. “Is there enough left for them to break fast?” The cook made two more rolls, and placed them on the platter. “I wish to see the house. Are you free to show me around?” Abigail asked Bentley.

As the two women walked up to the main floor carrying the platter, Bentley said: “I signed as witness to a deed that said your brother has purchased the house and estates. Does that mean the house is sold?”

“It does. William will speak to all the staff later, but rest assured you will be kept on. And paid your arrears of salary. I will be in charge of the household, so you should expect to report to me. Not the Duchess, who should be treated as an honored guest.”

“They will both be in the Duchess’s suite, I suspect,” the housekeeper said. She rapped twice on a door, and then opened it. A woman, wearing a somewhat tattered gown, was within, along with a girl of about 12 who looked to be squeezed into a dress of a 10-year-old.

“Is it time?” the woman said.

“Is that food?” the little girl said, salivating.

“We have food, and we have news,” Abigail said as Bentley approached the pair with the platter. They each quickly snapped up a bun and started eating, grinning as if they were eating a feast, not a common roll.

“It is clear which you wanted first,” Abigail said. “Now for the news. My brother, who is a cousin to the Duke, has purchased the house and the estates.”

“Gabrielle, eat like a lady,” the woman snapped. The girl took two smaller bites, and then went back to eating as fast as she could. Abigail noted that the bites her mother took were just as large. The woman continued: “When do we need to be out?”

“The thing is,” Abigail explained, “you are family, and you are not expected to leave. You are not even expected to move to other rooms. This will continue to be your home: even though it will be William that owns it, and not the Duke.”

“So he won’t be able to pawn or sell anything else,” the woman’s eyes lit up. “He will have to stop gambling.”

“William said he will allow 10 pounds a week allowance to the Duke, so he may continue his habits in moderation,” Abigail said. “But he will not be able to deplete the house or estates any further.”

“God bless you, cousin,” the Duchess said, hugging Abigail. “Bentley, put Abigail in the gold room. And have the lout of my husband moved into here.” She turned to Abigail and said in an aside. “I left the master suite three years ago, in an attempt to get him to stop gambling, but it just got worse. Your brother should get that suite. I will let John back in my bed, but it may be some time before he regains my attentions.”

She turned to Bentley, who had not moved, and was about to make a retort when she realized her mistake. “Oh my. It is no longer my place to order staff about, is it? That will be hard for me to break. I apologize.” She looked to two women standing at the wall. “Will we be able to keep our maids?”

Abigail had not even noticed the women standing motionless at the side of the room as they had watched their mistresses wolfing down food.

“Yes you will, but I will make one exception with this order,” Abigail said turning to the maids. “I want the two of you to hurry down to the kitchen and tell the cook that I said you were to be fed as the other staff have been.” She turned to Bentley. “And I will need a maid for my own purposes.

“Harper, send up Wilson before you eat, and then come back to serve your mistresses,” Bentley ordered.

Abigail looked around the suite. The only place one could sit was on the edge of the bed. There was an old wardrobe that had one door broken off, showing three or four old gowns. One was so old it had a ruff collar, a style that had gone out after Queen Elizabeth had died.

The Duchess blushed at seeing Abigail look about her room: “I apologize, milady. There is not much left in the house. We thought we would be moving out today. And my gown is not very presentable.”

“Neither is mine,” Abigail said. “I had to wear yesterday’s again, and that was a somewhat exciting day for us. I do have a trunk with a few more gowns, so I will be able to change for dinner. And let’s stop with this milady stuff. You outrank me: duchess over sister to an Earl. I am not even a Countess. Call me Abigail, or even Abi when we are alone.”

“I am Ruth,” the Duchess said. “This is Gabrielle.”

“I will have your trunk moved into the Gold Room, milady,” Bentley said, certain that the dropping of titles did not apply to her. “If you later wish another, then we can move you. I fear you will not be impressed with the room. There is not even a bed in it!”

With that the women toured the house. It had two main suites upstairs, the master quarters of the Duke, and the Duchess’s. There were eight other rooms: one for Gabrielle, and the Gold room that Abigail was moving into. The other six were slightly smaller, but still good-sized guest rooms fit for the visitors that would have come to the house in its better years. Now all the rooms were empty, to the point where carpets had been lifted and tapestries and paintings removed. Gabrielle’s room had nothing in it but a bed and a small table made of two wooden trestles with a plank over them and three other gowns spread over them, each older and more tattered than the one she wore.

“I think we need to go shopping tomorrow,” Abigail said. “We all need gowns and other clothes, and more than a few things to decorate these rooms.”

“There is no money for clothes,” the Duchess nearly sobbed. “We should stay at home while you go to the shops. Wilson can accompany you. “She is only a few years older than you, and knows the styles and the stores.”

“Nonsense,” Abigail said. “I will be both hurt and angry if the two of you, and your maids, do not accompany us. And you will get new clothes. My brother will pay for them. He will own them, which will prevent anyone from pawning them for gambling money.”

A wide grin appeared on Ruth’s face. “That is brilliant. We will be pleased to accompany you tomorrow, and will gladly wear any clothes you decide to lend to us.”

A young maid appeared at the end of the hall, and froze until Bentley noticed her and waved her closer. She timidly moved closer. Abigail recognized her from the breakfast: a thin, pale girl with beautiful long red hair to mid back. “This is Abigail Currie, sister to the Earl, and your new mistress,” Bentley said. “For the next two weeks you will be on trial with her as her personal maid.

“What is your name, dear?” Abigail said.

“Wilson, milady,” the girl said softly.

“That would be your father’s name, I think. What is your name?” Abigail repeated.

“I am Gloria Wilson, milady,” the girl said, nearly crying. “I am sorry, milady, but I have no experience in being a personal servant. I worked mostly in the kitchen, or in cleaning crews. Perhaps you would choose someone else?”

“Nonsense, Gloria,” Abigail said in a soothing tone. “Mistress Bentley recommended you, and I value her judgment greatly.” The housekeeper beamed. “It turns out that I have no experience having a personal maid wait on me, so we should fit together splendidly. We will muddle through things together. I know Mistress Bentley considers the two-week trial to be on my side only, but I promise you that if you want to go back to the kitchens at that time, you may. It will be a two-way trial.”

That seemed to calm the girl down, and when the other two maids appeared a few minutes later looking happier for having full stomachs, she fell into step behind them and they followed their mistresses through the house.

Soon after, men started moving furniture into the house, and a beautiful four-poster bed was moved into the Gold Room. Other furniture came in time, but when the women had seen all the house, and went out into the grounds. Bentley stayed behind to direct the delivery people.

It seems that Abigail’s suggestion that the staff start working had some effect. There was a slightly over-grown garden in the back, and there was a man working on trimming it back. Three other men were working elsewhere on the grounds, doing the front gardens, and mowing the lawn. The oldest man Abigail had ever seen, hunched over and able to move only by shuffling his feet, oversaw them. He looked to be eighty, if he was in the 21st century, although here he might only be in his late 60s.

The stable was nearly empty, although there were several men and boys in it clearing it up, and taking old manure out to the gardeners. The carriage they had rented for the day was inside, along with the four horses. While they were there, a vendor arrived with a wagon that held several sacks of grains, including oats. James, the carriage driver, seemed to be in charge.

“Greetings, miladies,” he said. “Your brother has hired me to buy this carriage and team from my prior employer. It will take a bit of work to get the place ship shape, but the lads here are eager and hard workers. You can drop that feed right here and the boys will take it in,” he said to the vendor driver.

“Me boss sed I weren’t to unload nothing till I saw the money,” the driver said. “It’s nine and five for the lot. Yer lot owes the boss money already.”

James flipped up a pound coin to the driver. “Take that. Apply the change to the account. And tell your boss that if he makes up an account of the rest of the charges owing, and gets us to us, it will be paid by the end of the month. And future bills will be paid monthly as well.”

The man started handing out huge cloth bags of grain to the men, along with several heaps of straw and hay1 that were dumped in the proper places in the stable. Soon the carriage team was being fed, and they eagerly ate the oats given them, and then worked more casually through the hay.

The women left the men to their work, and continued to circle the house. Abigail was astonished at how much maintenance had been let slide. Most window frames needed paint, and the stone work in a few places looked to need a mason. The Duchess told them that the roof was very bad, and needed work, and Abigail made a mental note to tell William, since that should be addressed as soon as possible. In the past when it rained, the staff would run from room to room, emptying buckets and pots containing rainwater, but two weeks ago all the spare pots had been sold to raise money. Apparently they tried to get the pots from the kitchen, and the cook needed to physically accost the men trying to remove her last cooking pots. In retrospect it sounded funny, like a situation comedy, but it showed how bad things were. Abigail noted that she needed to talk to the cook and find out if she had need for additional equipment, or foods beyond what Hockings had recommended that morning.

As they came to the back corner of the house, Abigail saw a building attached to the house that she didn’t recognize from her studies of 17th century architecture. It was round, with a domed roof, and a large door near the rear lane.

“What is that?” she asked Gloria.

“That is the icehouse,” the Duchess explained. “We used to store ice in there from the river every January. The ice would last until the following year, unless it was a really hot summer. It provided a cold room near the kitchen, so we could store meats for a longer time. Last couple years the Duke would sell of the ice when summer came and he could get a decent price for it. But last year he couldn’t afford the wagons to bring ice in at all. It sits empty now.”

Abigail thought for a moment. If the Duke sold ice in the summer, then there must be a vendor who could refill the room. Having even a rudimentary form of refrigeration would be useful.

They went into the house through a rear door near the icehouse, and were met by the smells from the kitchen, primarily the scent of pork being roasted. Abigail went down into the kitchen, but for some reason the Duchess and her daughter didn’t want to join them, and headed up to their suite.

The kitchen was a hive of activity. There was a large worktable that hadn’t been there before, and at least five undercooks were working on it preparing various items. As Abigail had worried, there was a squabble over pots, with the cook finally draining the beets into a serving dish and covering that with a towel to retain the heat, and then letting the other undercook use the pot. She was glad to see that there was a shelf covered with plates, platters, dishes and mugs that hadn’t been there in the morning.

“Milady,” the cook said. “Dinner in 25 … no 30 minutes. Is that young boy of yourn around? I needs a spit boy to turn the ham. I’se had use a wash girl, and that means others have to catch up fer her.”

“Thirty minutes? I need to go up and change. If I see Joe I will send him down.”

Abigail hurried up to her room, with Gloria following. She found a wardrobe had been installed in the room, but her clothes were still in her trunk. Abigail felt the need for a shower, but couldn’t wait the 300 years for one to be invented, so she just had Gloria help her out of her dirty clothes and into a second, cleaner gown.

The girl gasped, looking in amazement at Abigail’s large breasts. “Sorry milady,” she stammered. “I’ve never seen anyone so large. I had assumed you had padding or something in there.”

“Nope, it is all me. It’s like I’m following them around wherever I go. I don’t know if I’ll ever get used to them.”

“What? Did they grow that quickly?”

“Quicker than you might think,” Abigail said with a giggle. “But enough of them. More than enough of them, I think. Let’s get a dress on for dinner.”

As they walked down to the dining room, Abigail asked Gloria about cleanliness. She found out that the servants used an outhouse near the stables, but that there was an indoor facility for the family. But it sounded little better than an outhouse, albeit one that was shoveled out and rinsed weekly. Bathing was another matter. Apparently the Duchess called for a bath once a month, while the Duke, and most of the staff worked on the principle that one bath a year was one too many.

In spite of that Abigail insisted that she needed a bath that evening, and Gloria promised to have water boiled. There was a huge tub in the servant’s quarters that would be filled for her. It was stone, built into the foundations, so had not been pawned, as the Duchess’s upstairs tub had been.

Abigail walked into the dining room just as the cook was checking that all was ready. A huge new table dominated the room, and at one end the Duke and his wife sat on chairs, while the other end had William in one chair, and another that Abigail climbed into, with Gloria pushing it in close for her. Gabrielle was on the end of one bench, opposite her mother.

“This is ridiculous,” William said as he looked down at the Duke 24 feet away. The benches could hold eight to ten comfortably on either side, so up to 24 could dine here easily. “We need to get a smaller table for just six. It should fit nicely in that corner.”

With that the meal started appearing. First was a course of soup, which Abigail thought was bean, although she wasn’t sure. It seemed to need seasoning. The main course was ham, of course, and Abigail was only able to eat half of the slab that landed on her plate. The sides were turnips and beets; the latter still warm in spite of the pot debacle downstairs. Finally there was a sweet pudding for dessert that was a bit soggy, but still acceptable.

When Gloria cleared the plates Abigail asked what would happen to the leftovers: she had left a huge portion of ham on her plate, and more than half of the sides that were served with it. The girl whispered back that it would be eaten by the staff, who were just starting to eat downstairs. Abigail was happy to know that the food would not be wasted.

During dinner William and Abigail exchanged information on what they had done during the day. Abi mentioned the problems with the roof, and William ordered Hockings to look into the matter. “I am taking Joe and James out to where ‘the incident’ took place yesterday. And probably two or three of the men. I’d like to take the wagon, but that will be needed to bring in more supplies. I’m sending Kensing and Winthrope out shopping again tomorrow and they will need it. James says that the carriage horses are all trained to be ridden as well, so we will ride those. I’ll probably pick up another common horse to carry our gear. What do you have planned for tomorrow?”

“The ladies and I will be shopping as well. Since you are taking the carriage horses, I don’t know how we will get there though. Perhaps you can send for another carriage from the stage station. Tell them we want it for the day, but this time we won’t be buying it at the end and stealing another driver.”

Just then Bentley came up and told them that the staff had finished eating, and were being assembled in the great room. “Well, let’s join them. We need these benches for folks to sit on,” William said. “Abi and I can carry one, and you and Bentley can take the other.

“Sir,” Hockings said in an astonished voice. “Let me get some men to move them. It isn’t proper for the Lord of a house to do manual work.”

“Don’t be silly,” William replied, and he picked up one end of the bench, and Abi took the other, waiting while the amazed butler and housekeeper took the ends of the other and led to the great room, where the entire staff waited. Jaws dropped as they saw the new lord and lady carrying in a bench for them to sit on.

“Could four of you lads run back to the dining room and get the four chairs?” William said. “I want as many of the ladies as possible to sit on the benches, and the rest can be for the inside men. Those men who work outside can sit on the floor, I suppose. Eventually we will have the place furnished again.”

The servants milled about in confusion. “By ladies, the Earl is using the term broadly to mean all the women staff,” Abigail explained. The servants were amazed at being called ladies.

Soon the staff settled down, and William stood in front of his chair.

- There is a difference between straw and hay, although a city slicker might not recognize the difference. Hay is harvested grass and is quite nutritious as fodder for animals. Straw is the stalks of grain where the cereal head has been removed, and is used mainly for bedding for animals.

Times -- Ch. 04

Author:

Audience Rating:

Publication:

Genre:

Permission:

May You Live in Interesting Times

Chapter Four

“As you all must know by now, I am the owner of this house, since noon today. Some things will change, and this meeting will give us a chance to explain things to everyone,” William started.

“First of all, there will be few, if any changes in staff. All of you who have suffered through the past few years should be proud of your accomplishments in keeping the place going as long as it did. I think all of you are still owed salary. This will be paid in full. If any of you need your money immediately, see Hockings immediately after the meeting. I will also be available to discuss matters until after supper, but I will be out on business tomorrow. Hockings will also meet with most of you, starting after the meal and let you know what you are due to receive at the end of the quarter, when I propose that all arrears be carried forward.”

“Now, this is something for you to think on,” he continued. “Many of you will be receiving six or more quarters of pay at Michaelmas1. I propose giving you up to half in cash, and a note for the balance. The money on notes will be invested, and I expect that it will grow by about 10% per year in safe investments. Thus someone with 100 pounds will see that amount grow to 110 pounds after a year, and 121 pounds the year following. And if you add half your quarterly income in the future the gains will be more impressive. You will receive a statement at the end of each year telling you what your holdings are. If you leave our employment, then you will receive the full amount at the time you leave, or a week or so later. Imagine leaving to marry or start a business, and having perhaps £500 or more.”

“We will leave the money matters be for now. My sister and I are from overseas, and we have some different ideas about how things work. Hockings and Bentley tell me that most houses have a policy preventing fraternization amongst staff. Thus maids cannot become involved with manservants, etc. This bothers me. It seems that maids will reach a certain age, and then leave to marry and have children. The men will marry outside people, and then find they cannot support a household.”

“What I propose is that any staff member who has been with the house for over a quarter will be able to court any other member of the same status. The process is this: a young man who wishes to court a maid, would speak to the butler. The butler will speak to the housekeeper, who will let the maid know of the interest. If the maid is interested in being courted, then she tells the housekeeper, who tells the butler, who finally tells the manservant his interest is returned. From that point forth, there will be a set policy for courting. While details are yet to be completed, it will be something like this: for the first three months the couple will be allowed to sit and talk privately, with a chaperone present. During the following quarter, touching and holding of hands will be allowed. The quarter will allow kissing on the cheek or hand. The fourth three months will allow kissing, but still only in the presence of the chaperone. After a year, the couple may be engaged to be married, and if they do they will be allowed to continue to work in the house in their current positions. Family quarters will be provided.”

“And for those who are not so amorous, there is another innovation we will introduce. That is the day of rest. I know in most houses in the city staff are expected to work every day of the year. In the city apprentices and others are given at least Christmas off. Well we are proposing that every staff member will get one day of rest each week. For most it will be Sunday, but that is not hard and fast. For instance gardeners might get their rest day on a rainy day. And there needs to be staff to keep the house going at all times. This means that people will need to cross-train, which is a fancy way of saying someone else will have to be able to take over your job when you are off. Additional staff will be hired to ensure that we aren’t just making you all do seven days of work in six. And now my sister has something to say, I think.”

Abigail rose. “That’s a lot to take in, isn’t it,” she said lightly, and saw many heads nod blankly in response. “My offer is not so earthshattering. I understand that there are only a few members of the staff who can read and write. I propose to offer classes each evening to teach reading and writing to any staff member who wishes to learn. It is not a requirement to take these classes, but it will give each person an opportunity to advance. The young man shoveling manure in the barn might eventually become a future butler of this house if he learns to read and write, and do his numbers, which we will teach later. I am going to teach the class myself at first. If many sign up, then I will need help, of course. But this is an offer that this house makes to its employees.”

“It isn’t entirely for your benefit,” she continued. “If most of the staff can read and write, then we can send you a note asking you to do something, rather than going to you ourselves, or sending a message with another staffer with a chance of misinterpretation. It will make running this place more efficient, and hopefully a more fun place to work. Now, if none of you have any questions, we all have duties before supper. I can’t promise the same level as dinner was, but it will be better than you have had recently.”

“Gotta be better ‘n nothing,” one wag suggested as the meeting broke up, and this time it was the staff who returned the benches and chairs to the dining room.

Abigail planned to spend the evening making lists of items that would need to be purchased in her shopping trip tomorrow. She decided to head down to the kitchen first, where it was a hive of activity cleaning up after dinner and getting ready for supper.

Abigail approached the cook when it seemed that she had gotten all of her staff busy. “Mistress Boyle,” she said. “I am taking some of the ladies shopping tomorrow, and I wonder what you might need to get the kitchen fully equipped again. I heard earlier today that you have a shortage of pots.”

“Aye, milady, much of what was needed had been sold. I suspect that if you were to supply, say £50 or so I would be able to make up the supplies. The food you brought yesterday is enough for now, but we will need more in a day or two. Without ice, the meat will not last. And there are a few other things we are in need of. I could make a shopping trip one morning to replenish what we need.”

“I hope to get the icehouse restocked,” Abigail said. “Do you know who will have ice for sale?”

“I does, milady,” the cook said. “It will be dear to fill the house at this time, and really we only need half filled, since the hottest weather is past. It will probably cost £20 or so to meet our needs. If you could get me the money, I can arrange it.”

Abigail’s sixth sense flared. Why did the cook need cash? Suppliers were again accepting orders on account with the house. She leaned over to Joe, who was walking past, and whispered a few words into his ear. He immediately grinned widely, and then darted off.

“There is no need for you to go shopping, as several of us are making a trip tomorrow,” Abigail said. “We will pick things up for you. We just need to make a list”

“But you might not buy the right type of pots and such,” the cook protested. “I should see them so we get the right ones.”

“Surely you can describe them, and I will tell the merchant. If they are not the style or quality you need, you can return them and get what is needed. I don’t say that you will not go shopping in the future. It just doesn’t make sense for you to go tomorrow. And there will be no need for you to receive cash. Now that all our suppliers are accepting orders on account, you need not pay on the spot.”