The House In The Hollow: Chapter 1

Author:

Audience Rating:

Publication:

Genre:

Character Age:

TG Themes:

TG Elements:

Permission:

|

THE HOUSE IN THE HOLLOW

The sequel to 'Truth Or Consequences'

CHAPTER 1 By Touch the Light It’s finally happened. I stood on the shore of the mating game with Padraig and Gerald, Each illusory self is a construct of the

memetic world in which it successfully competes. Susan Blackmore |

Northcroft-on-Heugh, County Durham

May 19, 1979

Half-past eight on a warm, bright Saturday morning, and in the foyer of the Gladstone Hotel Sylvia is lingering.

Her beringed, scarlet-nailed fingers are toiling tirelessly, twiddling her beads and patting the diaphanous mesh she’s wearing over yesterday’s shampoo and set, whilst her false lashes are fluttering faster than a hummingbird’s wings.

She hasn’t had it this bad for a long time — but then we don’t often entertain guests as ruggedly handsome as Simon Whitaker.

He’s a self-employed demolition expert from Staffordshire — though his accent suggests he was born much further south — and is in Northcroft to oversee the removal of the railway station’s frontage and concourse. According to Sylv he’s thirty-two years old, divorced, and passes what little spare time his business allows him renovating classic cars.

So far, so what?

Except that her gushing directory of his manly attributes, which she raced into the bar to pour across me five minutes after he’d checked in last night, turned out to be no exaggeration. More than once during breakfast I found my gaze gravitating towards the table next to the fish tank when I ought to have been concentrating on the people I was serving, and if my mind kept warning me that it’s not yet ready to give in to my body’s physical needs and let a man sweep me off my feet, my nipples and the tiny winged creatures in my stomach weren’t listening. I don’t remember moistening my lips with my tongue — more than once, anyway — but there can be little doubt that a single flash of encouragement from those Robert Redford eyes and I’ll be tempted to indulge in a spot of lingering myself.

I might not have to do it for very long. Judging by the way he’s begun glancing from Sylv’s floral summer dress to my T-shirt and jeans, he certainly seems to appreciate what’s filling them.

After several abortive attempts, Simon manages to wriggle free from his would-be seductress and dashes upstairs.

“He can knock down my walls any time he wants,” Sylvia mutters as she lifts the hatch at the end of the reception counter.

I put down my duster and begin leafing through the copy of Au Courant lying beside the register.

“You’re smothering him,” I tell her, flicking back and forth between an article about the controversial new movie Jill Clayburgh is to appear in later this year and an ad for Max Factor that features some of the shades I might consider using when I finally get round to painting my nails. “Men need room.”

“Listen to the expert.”

I have to smile at that. When it comes to empathising with the opposite sex, I reckon I’ve got something of a head start on her.

“It’s still true,” I laugh.

“We’ll see which one of us lands him first. Oh yes, don’t think I haven’t noticed he’s turned your head as well.”

I arch my brows in mock outrage.

“How could you imagine such a thing?”

“I don’t need to. I’ve got eyes.”

“Mmm, so has he…”

“I thought so,” she grunts, vanishing into the office and by doing so missing the sight of my mouth falling open as I realise I said that aloud.

The telephone rings, and I force my jaws back together.

“Gladstone Hotel,” I answer in my sweetest sing-song voice. “How may I help you?”

“Good morning. I wonder if I might speak to Ruth Hansford-Jones?”

Male.

Mature.

Oxbridge vowels.

Succinct without being terse.

Military background a distinct possibility.

Gerald.

Shit.

“I’m sorry,” I say, hurriedly switching to what I hope sounds like a north-east accent, “Ruth doesn’ work ‘ere any more.”

“I see. Do you have her number, or perhaps a forwarding address?”

“I don’ know if I should be givin’ out that kind of information over the phone, pet. If yer want to leave a message I’ll do me best to make sure she gets it.”

“Very well. My name is Gerald Cooper, and my number is 0705 50389. I’d like her to ring me as soon as possible concerning Kerrieanne Latimer. Do you need me to repeat any of that?”

“Naw, I’ve got it all down,” I lie. “Is there owt more yer want me to tell ‘er?”

“That should suffice, thank you.”

I replace the receiver, then open the register and turn to the page containing Kerrie’s contact details. The telephone number she wrote down is the one Gerald quoted.

This has me scratching the back of my head. Is Gerald now living at 113 Woodford Road, in which case Kerrie must have returned from her trip to Belgium, or is he merely holding the fort while he waits for her to get in touch?

We have the situation in hand.

That was nearly three weeks ago. If Kerrie’s still trying to track down her daughter…

She can’t be. Suki’s people wouldn’t let her. They know what’s waiting for her in Bucovina. The risk of her becoming infected with the virus that took over Helen Sutton’s mind, then bringing it back to these shores, is too great.

You sly so-and-so, Gerald! Didn’t take you long to get your feet under the table, did it? I wonder what Rosie thinks about it all?

But why do you want to talk to me? I know Kerrie and I didn’t part on the best of terms, but if there was any news of Niamh or Cathryn I’d still expect to hear it from her.

I decide to call back later in the day, just to put my mind at rest.

Much later.

Shoving Gerald’s spring-coiled head back in its box, I go upstairs to make a start on the second-floor rooms. Just before I reach the landing I meet Simon coming the other way. We have to edge past each other, and there’s a moment when his left thigh becomes lodged in the gap between mine. Before he can free it, fate conspires to engineer things so that my breasts are pressed right into his diaphragm.

“They shouldn’t make the staircases so narrow,” he smiles.

“No…” I breathe, the little minx inside me letting him meet and hold my eyes for a second or five. “No, they shouldn’t…”

I get to the top somehow, and turn the corner without looking back to see if he was looking back to see if I was looking back at him. It takes me a few seconds to regain my composure; although I’m resigned to the fact that this body’s desires are rapidly becoming mine, the emotions associated with them are so different from the ones I experienced as Richard that it can be a real effort to keep them under control. It’s as if I’m undergoing some kind of mental puberty that will only end when the last layers of my male upbringing have been scraped away.

Don’t worry, babe. The time will eventually come when you’re lying in the arms of the man who’s just screwed you to within an inch of your life, shaking your head and wondering what all the fuss was about.

In the first of the rooms I’m due to service I begin stripping the sheets, blankets and pillows from the bed, tackling my duties with such vigour that I’m back in my Fortress of Solitude by ten past eleven, and giving me the chance to read a chapter and a half of Two Is Lonely before packing into plastic bags all the old jumpers, sweatshirts, jeans, and long, dark skirts I’ve decided to give to the next charitable organisation that comes a-calling. Summer — or what passes for it on the Durham coast — is approaching, and my wardrobe will soon take on a radically new look. Sylvia set things in motion when she donated an assortment of dresses, blouses and jackets she bought last year but never wore; the process is due to continue this afternoon when Janice drives us to Newcastle and we quarry Eldon Square for the latest separates and accessories. Although I can’t see myself strutting around in full ‘50s regalia just yet, my image will inevitably move in that direction. A girl well into her twenties ought not to come across as someone who’s trying desperately to persuade the world she can still cut it as a rebellious adolescent.

When the bags are all full I light a cigarette, noting that I’m down to my last three. Better if I head out to the newsagent’s now; if I wait until they’re all gone Sylv is certain to find me a job to do. First I have to swap my T-shirt — which I’ve just discovered has a coffee stain on the front — for the electric blue sleeveless jumper I plan to wear when we go shopping. And as it’s fairly breezy outside, I move my parting further to the right, comb back my fringe and spray it stiff. It wouldn’t impress Vidal Sassoon, but as a temporary measure it just about cuts the mustard.

Maybe I should heed Jan’s advice and have it all chopped off. Already the roots need doing, and I simply don’t have the patience to sit in a salon for over an hour with bits of paper or foil or whatever stuck to my locks, screwing up my nose against the reek of setting lotion. Give it a few weeks, then I’ll ask her to get rid of the dyed bits so I can go back to being a redhead. That’ll allow me to get used to wearing it short before I have it taken right off the ears for the trip to Lloret with my ‘parents’.

Shallow?

Sometimes I don’t think there’s enough water in my pond to submerge a fallen leaf.

My make-up refurbished and my bag checked, I trot downstairs to find Simon standing at the counter, going through the pile of brochures extolling the virtues of such ‘local’ attractions as Durham Cathedral, Whitby Abbey and the Captain Cook Museum on the outskirts of Middlesbrough. Sylv doesn’t seem to be around, so I saunter over to the spindle loaded with postcards featuring colour photographs of St Hild’s, the old pier and Battery Point, as well as sepia-tinted images of Northcroft from the early years of the century, in the pretence that the display needs rearranging.

“Hello again!” he says cheerily.

“Hello,” I reply with an insouciance I only just feign in time. “Looking for somewhere to go?”

His eyes loiter on my bare arms, betraying his surprise at how plump and freckled they are. Yet they also tell me he prefers that to them being too thin.

“I might not wander very far today. It’s the Cup Final this afternoon, and as Arsenal’s my team I don’t want to miss it. No, I’ll just exercise the old leg muscles for an hour or two, have a beer and maybe a bite to eat before I come back to watch the action.”

The Cup Final’s today? That shouldn’t be news to me, but it is.

“Arsenal? I thought you were from the Midlands?”

“I grew up in Hertfordshire. You’re a southerner too, if I’m not mistaken.”

“Actually I was born in Northcroft, but we moved to Kent when I was twelve.”

“Which accounts for the accent.”

I expect him to follow up by asking me why I came back to the north-east — in which case I can reveal that I’m recently divorced and therefore available. Instead he picks up a tourist map of the North Pennines and points to the sketch of High Force waterfall in the top right corner.

“Looks to be quite a spectacle,” he remarks.

I edge closer, though I can see the map perfectly clearly from where I am.

“Oh, it’s wonderful — specially at this time of year just after the last of the snow’s melted. The ground on the top of the hills holds water like a sponge, which means it’s constantly seeping into the streams that supply the rivers. Right now it’ll be in full spate, even though we haven’t had all that much rain recently.”

“You seem very knowledgeable!”

“Geography degree. Anyway, we used to go up there all the time when I was a kid.”

“I still try and do the occasional bit of rambling. Dovedale, mainly. When I get the chance, which isn’t often these days.”

I indicate the area to the west of Middleton in Teesdale.

“My favourite spot was somewhere around here. It’s called Low Force, ‘cause the falls are lower down the river, obviously. There’s a rickety old suspension bridge, and loads of huge rocks where you can sit and have a picnic. I’d often go down to the water’s edge and just listen. It’s ever so therapeutic.”

His blue eyes widen, becoming even more beguiling.

“You’ll have to show me,” he smiles.

I’m not sure what expression my face serves up. I’ve been asked out many times since I came here, Peter Sewell being the most persistent of my aspiring suitors, though never by anyone whose company I’d enjoy enough for me to forget my qualms about taking what is after all one hell of a leap into the unknown.

But whatever Simon thinks my reaction is, it’s not the one he was hoping for.

“I’m sorry,” he groans, putting a hand to his forehead. “I overstepped the mark there, I know.”

“Not at all. I’d love to.”

It’s on sale in all good bookshops before the editor has had a chance to open the manuscript, let alone proofread it.

And the man whose proposition I’ve just accepted likes what he reads on the back cover.

“So if you’re free tomorrow…”

“We could have a drive over.”

Oh look, there’s volume two — rushed off the presses as hastily as its predecessor.

“In that case I’ll meet you here at…is eleven thirty too early?”

“It’s fine.”

Ruth Pattison one, Sylvia Russell nil.

I grab my bag and make a beeline for the door in case either of us changes their mind.

It’s finally happened.

I stood on the shore of the mating game with Padraig and Gerald, but did no more than poke a toe into the surf. Now I’ve waded in with both feet, and I’m waiting for the first real wave to break.

Let’s hope I prove to be a strong swimmer.

The red Mini Minor I can see parked in the forecourt when I return from the newsagent’s renders me as motionless as if I’d just banged into an invisible wall. It pushes aside thoughts of romantic walks beside the burbling waters of the River Tees and replaces them with memories of an altogether less pleasant nature.

Trisha Hodgson and her brother-in-law have been digging. We’d prefer them to desist.

Meaning it’s my job to talk some sense into her. If I can’t, goodness knows what the MoD might do.

The woman in that room. She’s not my mother.

No, she isn’t. But the real Carol Hodgson died along with Richard Brookbank’s body, and nothing her daughter does will bring her back.

Maybe I should crack open a bottle of tough love and send her on her way.

Then I recall that Trisha now owns the house where Helen Sutton once lived. Perhaps the only reason she’s here is that she and her boyfriend have been looking the property over, and felt it would be discourteous to leave without saying hello.

It transpires that she’s alone — and looking very summery in her demure, light green maternity dress as she stands at the reception counter reading the magazine I left there earlier.

I suddenly find I’m unable to be too hard on her. I need female friends; Trisha will have plenty, and to spare. Nor must I forget that her experiences as a mother-to-be are sure to provide valuable lessons I can draw on when I’m carrying a child of my own.

She turns at the sound of the door.

“You’re coming on quickly!” I exclaim, pulling her into a careful hug.

“Getting fatter every day,” she pouts.

I step back — but only a little way, so hopeful am I that I’ll feel her baby move against my middle.

“Notice anything different about me?” I ask.

“Different?”

“My hair, for example?”

“Your hair? Yeah, it suits you.”

She was quick enough to remark that I’d gone ginger. Whatever’s preying on her mind, it must be serious.

“How long have you got to go?” I enquire.

“She’s due on July 15th.”

“So it’s definitely a girl?”

“Oh, we’re quite sure of that.”

“Thought of a name yet?”

“Helen.”

“Not after Miss Sutton, I hope?” It’s a joke, but she seems far from amused. Time to change the subject. “Did you know my divorce came through?”

“Did it? Congratulations.”

“Yeah, I’m back to being Ruth Pattison again.”

“Good.”

She hasn’t cracked her face once since the conversation began. I’m starting to feel like a mourner at a funeral who can’t keep quiet about the new outfit she’s just bought.

One last try…

“My parents phoned the other day. They actually invited me on holiday with them. The Costa del Sol, no less.”

“Lucky you. The furthest some of us’ll get this summer will get is the maternity wing at North Tees.”

I’ve had enough of this.

“Okay Trish, out with it. What’s your mum said now?”

For a moment or two her features just freeze. Then she grabs my hand and pulls me into the lounge. After a quick look to check that the foyer is empty, she closes the door behind us.

“This has nothing to do with her. Not directly, anyway.”

She digs inside her purse. From it she takes a neatly folded piece of notepaper. When I see what’s written on it my frown is so pronounced it’s almost audible.

SUNNY HOLLOW, RAIKESDALE ROAD, ELLERBY, NORTH YORKS

…a couple of the teenagers who found dad’s body on the beach sneaked back through the police cordon just before it got dark and saw them zipping two more bodies into black bags.

“Are these the girls you were on about before? I thought they’d disappeared from the face of the earth?”

“It isn’t unusual for retired deputy headmistresses to have friends in the Education Offices. There’s all sorts of information on file if you know who to ask.”

“You mean your mum found it for you? Last time you were here the two of you were barely on speaking terms.”

“She apologised. We’re friends again.”

“Have you been in touch with them?” I ask, praying she’ll say no.

“They’re not on the phone. But we can at least…don’t look like that, it’s only twenty miles away.”

“Then it won’t take you very long to drive there, will it?”

“Come on, Ruth! You know how important this is to me!”

“What’s wrong with asking what’s his name, Paul? Or your boyfriend?”

“They’re both busy all weekend.”

“Well guess what, so am I!”

“Fine. I’ll go on my own.”

I do my very best to dissuade her from following this through. If Suki Tatsukichi’s bosses wanted those girls to vanish then vanish they would. That Trisha’s mother located their whereabouts so easily suggests the involvement of an outside agency, and it’s clear to me which one.

She has friends in the highest of high places.

Yvette de Monnier.

Using her hold over the woman calling herself Carol Vasey to stir up trouble.

But why do the whirlpools she creates have to suck me in every time?

In the end I agree to drop out of this afternoon’s shopping trip and resume the role of trusty sidekick. Apart from anything else, I can’t let a girl who’s nearly seven months’ pregnant blunder into another of de Monnier’s intrigues without someone to watch out for her. She’s lost enough because of that selfish bitch already.

Sylvia receives the news with a characteristic shrug of the shoulders.

“I know better than to argue with you,” she sighs. “Just be wary about what you’re getting yourself into. Remember what happened after you and Kerrie Latimer went sticking your noses in where you shouldn’t have.”

As if I needed reminding.

Trisha is on the telephone when I get back to the foyer, speaking in a voice so soft and low that I have to assume her boyfriend is on the other end of the line. She ends the call, then rolls her eyes.

“He who must be obeyed,” she grins, picking up her bag. “Men have such a high opinion of themselves, don’t you think so?”

“Some of them, I suppose.”

“They don’t realise that all they’ve ever been good for is to put food on the table and keep us warm at night.”

“Those are two quite important tasks,” I point out as she takes my arm and we begin making our way outside.

She’s unlocking the car door before I remember that she still hasn’t mentioned her partner’s name.

But then she’s Trisha.

Not so much a law unto herself as a complete Hammurabic Code.

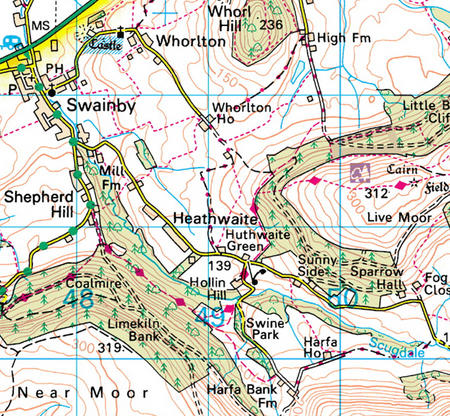

Less than half an hour’s drive from the clamour and smog of industrial Teesside — even the name sounds toxic — lies one of England’s best-kept secrets, the North York Moors. Its most spectacular feature is the thousand-foot high escarpment known as the Cleveland Hills, against whose bracken-covered slopes the lowlands wash in gentle, pastoral ripples. The rounded summits form a broad curve that tends west and then south, their course paralleled by the main road that connects the market towns of Stokesley and Northallerton. A few miles before its intersection with the A19, we take the short side road that brings us into the sleepy village of Ellerby.

“Where to now?” I ask Trisha as she guides the Mini onto a narrow bridge that crosses a sluggish, reed-filled stream.

“According to the map it’s straight through the village and keep going.”

“You bought a map?”

“There was one in Stockton library. They wouldn’t let me make a copy, worse luck.”

The surprisingly long main street steadily turns into a country lane as the buildings on either side become more dispersed and are gradually supplanted by fields, some used to graze cattle and sheep, others growing fodder crops. After a few minutes the gradient begins to increase; the hills, some of which are clothed with extensive belts of conifers, close in. We come to what must at one time have been a railway crossing — one of the gates is still there, and behind it stands a derelict guards’ van — and then a junction at which we bear left, climbing a bank bordered with high hedges, the road scarcely wide enough even for the tractor ambling in front of us.

Trisha changes gear for one more steep, winding ascent. At the top, beside a stone building with an arched doorway, is parked a Dormobile. She pulls in a few yards further on and switches off the engine.

“That can’t be it,” I say to her. “It’s just a barn.”

“See the gate on the other side of the road?”

I look past her, my gaze finally landing upon the concealed entranceway she indicated. Beyond the gate, trees lean over a rutted track that drops abruptly into shadow; through them I’m able to glimpse the rough pastures and knots of woodland falling to the valley floor, but little else.

“Are you sure about this?” I ask as I open my vanity case and begin refreshing my lipstick.

“I want answers, Ruth. I’m not going to give up until I get them.”

I refrain from telling her there are things the MoD has decided it’s better for the general public not to know. Let her come to that conclusion herself.

We pick up our jackets, lift the straps of our bags onto our shoulders and climb from the car.

“So where’s the house?” I ask, pushing open the gate.

“Hidden from the road, obviously. Maybe that’s why they chose it.”

She slips her arm through mine. I brace myself to take her weight.

“You won’t be able to fit behind the wheel soon,” I quip. “Sure it’s not twins?”

“There’s only Helen,” she replies, again failing to see the funny side of my remark.

I lead us forward, taking care not to lose my footing on the uneven ground. The track veers to the left, then merges into a grassy terrace some fifty feet across ending in a confusion of bramble, holly and yew. Opposite, fronted by a gravel forecourt, stands a large but otherwise unimpressive two-storey dwelling that invokes images of a giant hand lifting a house from one of Northcroft’s dowdiest streets and plonking it here just for fun.

“Sunny Hollow,” I murmur, noticing the lack of space between the back of the house and the cliff rearing above it. “I bet whoever called it that didn’t spend much time in the kitchen.”

Trisha releases my arm and makes straight for the front door. She raises her hand to ring the bell, but I’m too quick for her and manage to block it with my palm.

“What’s wrong?” she wants to know.

“I’m not sure. Something is.”

“You’re being silly.”

“No, I’m being cautious.”

Suddenly her eyes are ablaze.

“That’s a baby crying!” She waddles over to the window. “Look, a cot!”

Before I can join her, I hear the sound of a dustbin lid being raised behind the wooden fence at the far end of the building. Then a gate opens; we turn to see an attractive if quite heavily built woman, perhaps just short of forty, wearing a black pinafore dress over a short-sleeved white jumper. Her dark hair, unblemished by even a hint of grey, is brushed forward into a long fringe and tumbles loosely to her shoulders.

“May I be of assistance?” she enquires starchly.

“We’re looking for Donna Parker and Louise Dixon,” replies Trisha.

“Gillian Dixon — Louise’s mother.”

Gillian has noted Trisha’s condition, and seeing no threat from her proceeds to fire the full force of her mistrust directly into my face. It’s a searching examination, yet I’ve been through too much to be rocked back on my heels by a housewife.

“We’d like to talk to her, if that’s okay with you,” I say hopefully.

“The others have gone down to the village,” she informs me in a voice that couldn’t lack much more warmth if the words had been forced to fight their way out of her mouth with ice picks. “If you come in you’ll be supplied with refreshments while you wait for them.”

“This doesn’t feel right at all,” I whisper to Trisha as we follow Gillian through the gate and into a paved yard wet from having recently been washed clean.

“Whatever’s got into you?” she laughs.

“The way she talks. Her eyes. Everything about her is just weird. And did you notice she hasn’t asked us who we are or how we know her daughter?”

We walk through the dingy but fully fitted kitchen and enter a spacious living room. The walls have been stripped bare, and every item of furniture is draped with an old sheet. The two doors in each of the corners to our left are open; the nearer gives onto a stairwell, the other to what appears to be a dining area.

“Hope you both like tea,” says Gillian, uncovering a chintz sofa for us. “It’ll have to be Chinese. Donna bought rather a lot when she visited York last week.”

A teenage girl who spends her money on Chinese tea? This gets stranger by the minute.

While Gillian is out of the room Trisha amuses herself by making a fuss of the baby. I’m drawn to him too, speared by the desire to pick the gurgling child from his cot and hold him against my breast — not that I’d dream of doing such a thing without his mother’s permission.

“What’s his name?” I call into the kitchen.

“Philip. He’s Louise’s son.”

Trisha and I exchange a look. The child appears to be only a few months old, which means that Louise must have been pregnant with him when the MoD spirited her away from her home.

Our host returns with a tray bearing a willow-pattern pot and three matching bowls. She places it on the sideboard, clearing a space by moving aside a packet of disposable nappies.

“This is a first for me,” I confess.

“You should leave it for between three and five minutes to let it infuse properly,” Gillian advises me.

There follows an uncomfortable silence, which Trisha brings to an end when she remembers that a set of documents she intended to show Donna are still in the car. I offer to fetch them for her, but she’s adamant that being pregnant doesn’t make her a helpless invalid.

Finally the tea is deemed to be ready. Gillian pours it out, then suggests I sit at the kitchen table so she can talk to me while she prepares Philip’s bottle.

“How is it?” she asks, watching me lower the bowl from my lips.

“It’s an unusual flavour. Not at all what I expected.”

“That’s the ginseng. You’ll soon get used to it.”

The liquid quickly cools down, enabling me to take several more sips without scalding my tongue. I glance up at the clock on the front of the cooker; the hands are difficult to see, so little light is there.

I make a tactful attempt to bring up the subject of Bob Hodgson’s death and discover that I can’t be bothered to finish my sentence. For some reason the subject just doesn’t strike me as important any more.

Gillian tests the temperature of the baby formula on the back of her wrist. She goes into the living room to collect Philip, who immediately launches into a protracted wail, waves his arms about and refuses to allow the teat anywhere near his mouth.

“He’s upset, the poor little thing,” she explains. “His grandmother doesn’t usually look like this, that’s the problem.”

I want to ask her what she’s talking about, but come to the conclusion that it’s too much trouble. I think about checking to see if Trisha’s all right, because she’s taking longer than she should be; then I find I can’t even summon the enthusiasm to stand up.

Only when Gillian takes off her wig, and I stare in horror at the crest of black gemstones set in her shaven scalp, am I motivated to stir myself.

And then I’m unable to move a single muscle.

When my eyes finally close it comes as a blessing.

To Be Continued...

The House In The Hollow: Chapter 2

Author:

Caution:

Audience Rating:

Publication:

Genre:

Character Age:

TG Themes:

TG Elements:

Permission:

|

THE HOUSE IN THE HOLLOW

The sequel to 'Truth Or Consequences'

CHAPTER 2 By Touch the Light The door creaks open. My head snaps round, and I almost pass out at the sight of two living, breathing kuzkardesh gara. |

I am neither a neuroscientist nor a cognitive psychologist, and claim no expertise in either field. My knowledge of memes is based on a layman's reading of works by such authors as Richard Dawkins, Daniel Dennett and Susan Blackmore. I have extrapolated some of their ideas in this and the three chapters that follow, but all I'm really doing is making a few reasonably well-informed guesses.

I wake to find myself stretched out on a soft bed, completely naked. My arms are by my sides, and feel so heavy I can scarcely move them. When I try to lift my head from the pillow, the room spins so fast that the bile rises in my throat and I have to spit it onto my chest to prevent myself from throwing up.

Whatever Gillian Dixon put in that tea, it’s rendered me as feeble and defenceless as her daughter’s baby.

His grandmother doesn’t usually look like this, that’s the problem.

More brutal than the memory of some unspeakable act of violence, the picture of Gillian’s bald, jewel-crested head crashes into my mind, takes up residence there and refuses to leave.

When did she become a kuzkardesh gara? Who infected her, and where are they now? And what were the MoD doing while this was happening?

Pissing about forging wills and breaking into dead people’s houses to leave caskets behind, that’s what.

Fucking idiots.

But I can’t afford to let my temper get the better of me. Just as I did at Hayden Park, I force my mind to concentrate on making a thorough assessment of my immediate surroundings.

The room is smaller than the one I occupy at the Gladstone, roughly fifteen feet by ten. The door is in the left-hand corner as I look, and stands slightly ajar. Either I’m free to wander around as I please, or Gillian doesn’t expect me to be in any condition to make a run for it.

Trisha certainly isn’t, drugged or not.

Where is she? Christ, I hope she managed to get away.

Wait a minute, how did Gillian get me up here? I’m not the most sylphlike of girls; brawny as she is, it would have taken her five or ten minutes to drag me upstairs, and Trisha had only gone out to the car. Surely she’d have caught the bald-headed cow in the act…

Unless it was no coincidence that she left when the tea was about to be served.

Or that Gillian just happened to be wearing a wig when we arrived.

You’re being paranoid, babe. The very idea that Trisha lured you here under false pretences is too ludicrous for words.

Yet she’s got the same hairstyle as Gillian, brushed forward to hide her forehead…

Men have such a high opinion of themselves, don’t you think so?

And she wouldn’t tell me her boyfriend’s name…

They don’t realise that all they’ve ever been good for is to put food on the table and keep us warm at night.

Didn’t Susan Dwyer say something like that?

They are necessary to perpetuate our species, and to provide for us when we’re carrying and raising our children. In return we pleasure them, in ways most have never dreamed of.

The evidence is mounting up. It points towards only one conclusion: Trisha Hodgson, the girl I once loved more than life itself, is now a member of the same bizarre religious cult that Helen Sutton joined shortly before she died.

As nightmares go, that doesn’t so much as take the biscuit as run away with the whole barrel.

How could I have been so stupid? I knew there was something amiss as soon as she showed me Donna and Louise’s address. And yet I still barged headlong into what I ought to have realised was a set-up.

Not only that, but she managed to fool me into thinking there was nothing the matter with her.

No blame attached to you there, babe. It was one hell of an effective disguise.

Maybe, but that’s small comfort.

How many more of these women are walking unseen among us? How bad has the situation become?

If this menace gains control then that’s it. Full stop. Period. Punkt. Bye-bye progress, bye-bye creativity, bye-bye all the things that make us human. For ever.

After a few false starts I raise my hand far enough to check that I’ve still got my hair. The feel of it beneath my fingers — and what a blessed relief that is! — provides me with the impetus I need to drag myself to a kneeling position so I can look through the window to the right of the bed. The view is restricted by the sides of the hollow in which the house is set, but allows me a glimpse of the wooded hills on the south-western side of the valley. From the altitude of the sun I can tell that it’s quite late in the afternoon.

Trisha can’t have gone for help. It would have arrived long before now.

The woman in that room. She’s not my mother.

You stupid little tart! Why couldn’t you have left things alone?

I swing my legs round and instantly wish I hadn’t, for the nausea that sweeps through my system has me sitting with my head bent forward and dribbling like a senile old woman. It’s several minutes before I recover sufficiently to take note of the pinewood wardrobe and matching chest of drawers facing the window, or the dressing table to the right of the door whose surface is filled with bottles and jars disturbingly similar to those Kerrie Latimer and I came across in 6 Redheugh Close — as well as a stand holding a wig identical to the one Gillian Dixon wore.

The reason for my being here couldn’t be more plain.

If I didn’t feel so sick I’d laugh until I needed a hip replacing. Who do they think they’re dealing with? As soon as I can stand without the world turning somersaults around me I’m going to find that teapot and ram the snout so far up Gillian Dixon’s vagina I’ll be able to hang my coat on the back of her neck.

None of my clothes are anywhere to be seen, so I risk crawling across to the chest of drawers in the hope that it’ll contain something to cover my nakedness. A pair of black lace panties partly fulfils my requirements, but there isn’t a bra to be found — and the rest of the lingerie consists exclusively of suspender belts and pairs of seamed stockings.

Fine for the first time I sneak down to Simon’s room.

Not a great deal of use to me this afternoon.

When I open the wardrobe, it comes as no surprise to learn that the rails are hung with sleeveless black dresses. Yet when I pull one of them out I notice it lacks the diaphanous bodice that characterised the garments we found in the casket. Instead there’s a large heart-shaped hole cut into the material just below the collar, the edges machine-stitched and clearly not to factory standards.

Then I see the label attached to the inside.

“Marks and Spencer’s?” I gasp. “Marks and bloody Spencer’s?”

The others all carry the same tag. They’re common or garden retro ‘50s frocks that have been altered solely for the purpose of showing off the wearer’s breasts.

And this is a religious movement? What’s their holy book, Erica Jong’s Fear of Flying?

I sit at the dressing table and go through the various compartments, bringing out an assortment of necklaces, rings and loose stones that appear to be made of nothing more precious than coloured glass. Thankfully I don’t see any spiked leather chokers, dog leads, whips or sets of handcuffs…though it’s early days, I suppose.

The door creaks open. My head snaps round, and I almost pass out at the sight of two living, breathing kuzkardesh gara.

They move into the sunlight, which glints off the black gemstones set in their shaven scalps and brows, as well as those dangling from their ears, strung along the chains hanging almost to their waists, and mounted upon the silver rings adorning their fingers and thumbs. It shines equally brightly upon the ebony paint covering their lips, their nails and even their nipples.

Gillian — I can only distinguish her from the other because she’s the stockier of the pair — reaches out to stroke her companion’s cheek. The gesture is reciprocated with what I have to admit is genuine tenderness.

But any chance that my hostility towards the pair might weaken is removed when two smaller, much younger converts appear behind them — one of whom is rocking a baby in her arms.

A teenage girl, for heaven’s sake.

A teenage mother!

Now I’m really angry. I want to know who’s responsible for this. I want them punished and I want them shamed.

And if the MoD try to keep it quiet I’ll blow the whistle on the whole fucking lot of them.

A figure has appeared on the landing.

Trisha! And she’s fully clothed!

I have the presence of mind to yank the counterpane from the bed and drape it around my shoulders before barging past the inhuman creatures blocking my path.

“Quick! We’ve got to get out of here!” I yell, grabbing her hand.

She doesn’t move.

“I can’t take you back with me,” she says quietly. “Not after everything you’ve done. They told me what happened on the night dad died. You were trying to blackmail Miss Sutton into changing the will. That’s why she ran down to the breakwater, to get away from you.”

I stagger away from her, unable to believe what I’m hearing.

“I don’t know who you’ve been talking to,” I pant, “but they were lying.”

“Were they? I’ve seen one of the letters you wrote to her. And I know all about the casket, and the reason you sent it. Personally I think you’re getting off lightly. But at least this way the punishment fits the crime. Enjoy life as a kuzkardesh gara, Ruth.”

Her words slice my guts wide open. I slide to the floor and sit there with my head in my hands.

The reason I came to see you, Ruth, is to inform you that we’re taking you off this case with immediate effect.

You bastards.

I’ve outlived my usefulness, and now you’ve found the perfect means of erasing me from the picture.

I will never forgive you for this.

Never.

When I finally lower my arms, Trisha has gone. I look up to see four sets of ebony lips curl in identical malignant smiles.

“Welcome to your new home, Ruth Pattison,” the kuzkardesh gara chant in unison. “Welcome to the Sunny Hollow hive.”

The bathroom at Sunny Hollow is a modern extension, built into the back yard from the bottom of the staircase. The tub takes up the whole of the left-hand wall, and leaves only enough floor space for a lavatory and a washbasin. Above the latter is a cabinet fronted by an oval mirror; inside I discover a rack containing five toothbrushes, one of which is still in its packaging, and shelves filled with such commonplace items as antiseptic creams, headache tablets, vitamin pills, sanitary towels and mouthwash.

All of them will have cost money.

Village stores don’t give away bags of groceries and other provisions. Electricity accounts aren’t famous for settling themselves.

Someone is financing this enterprise.

And I have a good idea who.

The door opens — the bolt has been taken out of the lock — to admit Gillian.

“There is so much we have to tell you, Ruth Pattison,” she says mellifluously.

“Fate has brought you to us for a very special reason,” adds Louise, materialising at her side and touching a bejewelled, black-nailed finger to her mother’s upper arm.

I don’t reply straight away. Instead I battle back my rage so I can figure out what it is about their faces that strikes me as off beam.

That’s it!

They don’t have those intricate patterns of dots going back from the corners of their eyes I remember from the photgraph of Sarah-Jane Collingwood.

Why not? Is it possible that their commitment to the cause isn’t all it might be?

Hair grows back. Nail varnish, lip gloss and costume jewellery can be removed. Tattoos are a different kettle of fish entirely.

Are they merely trying this out, in the same way that impressionable youngsters sometimes become animal rights activists or join groups of squatters? I could believe that of Louise and Donna, but their mothers? How could two mature women allow themselves to be taken in by this rubbish?

The pair turn from me and begin communicating in a private language of clicks, whirrs and sibilant whispers. More unsettling than the sounds themselves is the sight of their eyes glazing over when they make them, as if they’re robots whose power packs have run out of juice. They remind me of how Susan Dwyer’s face changed when she told me humanity was doomed.

The genie is out of the bottle, and no one is going to put it back.

You don’t know us, you ugly half-human bitch.

Once again I make an effort to stop my temper from boiling over. I’ve got to play this very carefully indeed. Whatever I do, I mustn’t give them an excuse to drug me again. Gillian and Donna’s mother — did she say her name was Hilary? — both have an advantage over me as regards height and weight; I’m confident I can outwit them, but only if I stay fit and alert.

I’m more concerned about what might happen after I’ve escaped. Trisha’s bound to have concocted some cock and bull story she’ll use to explain my absence. I only hope in the light of what she said earlier it doesn’t prove too damaging.

“So what happens now?” I ask the insectile duo, as much to interrupt their hissing and chirruping as anything else.

“You should get dressed,” answers Gillian, gesturing upstairs with her fake oriental eyes.

“What, go around in that clobber you left in the wardrobe for me? I think I’ll have my own clothes back, if it’s all the same to you.”

“That is out of the question.”

I take a step towards her.

“You don’t fool me, darling. You’re playing at this, aren’t you? I’ve seen a photo of the real thing. You’re just an imitation, and not a particularly good one either.”

“The replication process is never absolutely faithful,” she smiles. “If it were, the meme would have no opportunity to evolve. However, your invective explains your initial response to our appearance, which was one of repugnance rather than surprise. Aware of what we are, you feign a sense of outrage in order to disguise your true intentions, which are to pretend to go along with us until you have succeeded in getting us to let down our guard enough for you to attempt to leave. That we cannot permit.”

“I’m a prisoner, then? Says a lot for your ‘hive’ and its beliefs if it can only make new converts by holding them captive. How many of you termites are there, by the way?”

“There are enough of us to serve the purposes of the universal female mind,” answers Louise.

“You mean it’s just the four of you? Really?”

“We set an example for others to follow,” declares Gillian. “They will come to us when they are ready. As will you.”

I push my bare breasts right into her chest. To her credit, she doesn’t flinch.

“I’m not sure what you think you hope to achieve, but you’ve picked the wrong babe to fuck about with.” I exert even more pressure. “Why are you so keen on keeping me here, anyway? What’s so special about me?”

“That will become clear to you soon enough,” Louise puts in.

“You have a destiny to fulfil, Ruth Pattison,” says her mother, her face so close I can feel her breath against my cheek. “The enemy have unwittingly presented us with what we are now certain will be our most powerful weapon.”

I narrow my eyes.

“What are you talking about?”

“You must dress,” insists Louise.

I open my mouth to protest, but realise there’s little to be gained by arguing with her. Besides, if I make a break for it I won’t get very far in just a pair of knickers.

Donna is standing outside the door to my room, like some hideous parody of a serving girl. She invites me to sit on the bed while she puts together my outfit.

“You’re wasting your time,” I tell her as she lifts my left foot and slides it inside the first of the stockings she’s selected for me. “I won’t weaken.”

“We do not anticipate that you will,” she says enigmatically.

I’m left to fasten the suspenders myself. It takes me a minute or two — there’s a knack to it, and my fingers don’t seem to ‘remember’ it all that well. Yet although I’d probably have changed from tights to stockings as soon as I started wearing ‘50s clothes on a regular basis, it still feels like putting on the opposition’s colours.

That impression is strengthened when I step into the dress Donna holds out for me. The one consolation comes when I gaze down at my naked breasts and realise I couldn’t have two more prominent reminders of the need to fight for my freedom.

“Satisfied?” I grumble as I bend down to slip on the black high-heeled shoes the kuzkardesh gara has picked from the dozen or so pairs I saw at the bottom of the wardrobe. “Tell me, where did you witches get the idea that you’ve got to go around with your tits hanging out? Did our Chrysanthemum moonlight as a stripper before she caught the anthropology bug?”

“Frau von Witzleben was a great admirer of Minoan culture,” answers Donna.

“Ancient Crete, eh? Good job she wasn’t interested in pre-colonial Africa, or you’d all have bones stuck through your noses.”

Not a flicker.

No sense of humour, then. That figures.

Bye-bye progress, bye-bye creativity, bye-bye all the things that make us human.

Donna adjusts my collar — as if anyone’s going to notice it with what I’m advertising on the shelf below. Her mouth shapes itself into a rictus of distaste when her hand comes into contact with my hair.

It serves no purpose other than to feed the chimera of selfhood.

My eyes are drawn to her scalp. There isn’t the slightest trace of stubble. It’s as shiny and smooth as I’d expect it to be if her head had been shaved only a few minutes ago.

That could be you, babe, if you allow this mental virus to worm its way inside your mind.

I’ll throw myself off Blackpool Tower first.

“We should join the others,” says Donna. “The evening meal is ready.”

I follow her downstairs, the sight of my breasts bouncing and swinging only adding to the sense of betrayal raging within me.

But they’ve forgotten one thing: I’ve put in too much hard work becoming Ruth to allow myself to be walled up in a place like this.

I’m getting out of here.

And when I do, Sunny Hollow is going to be on the front page of every newspaper in the country.

Hilary Parker inclines her head and hisses three guttural syllables into her daughter’s face. In reply she receives a single click of the tongue; the sound is clearly meant to indicate agreement, as both immediately rise from the table and begin piling together the plates, bowls and spoons they set out earlier for their so-called meal.

I watch the kuzkardesh gara carry them from the dining room, resolved not to let my gaze fall upon the sinister crests of black gemstones that seemed to pulse and vibrate in the artificial light as they fed.

If only it were as easy to ignore the fact that the MoD, in their infinite wisdom, have set up an experimental hive in the middle of North Yorkshire.

“They want to know how fast a collective mind grows, whether the expansion is regular or exponential, and what effect its presence has on the local community,” Louise told me before she left the table to see to her baby. “As long as we refrain from drawing too much attention to our activities they have promised to leave us alone.”

They’re lab rats.

And I’ve just been dropped into the cage.

“You have not eaten very much,” frowns Gillian, gesturing with beringed, black-nailed hands at the plate containing the flavourless lentil-based mush I toyed with for all of thirty seconds before I pushed it away in disgust.

“Arrange the following appetite suppressants in order of effectiveness: drugged; being held here against my will; having my clothes confiscated; listening to you lot jabber on like overgrown cockroaches…oh, and being served something that looks like it came out the backside of one of those cows down by the beck.”

“This is all for your own good, Ruth Pattison. You will thank us for it when you come to recognise the illusory nature of the individual self.”

“I’ll decide what’s good for me, thank you very much. Now I haven’t had a cigarette since a quarter to eleven, so unless you fancy me showing you just what a bad-tempered bitch I can be when I’m deprived of my nicotine fix I suggest you hurry along and fetch me my bag.”

“We do not smoke,” she says coldly.

“Well I do, and I’m gasping. Don’t worry, I’ll go outside. You won’t have to breathe any of it in.”

“The hive requires you to abstain from stimulants of any kind.”

“Then the hive can piss off.”

The kuzkardesh gara touches a finger to the black gemstone set in the centre of her forehead.

“Are you not curious as to how Gillian Dixon came to discard the illusion of selfhood?”

“What d’you mean? You’re Gillian, aren’t you?”

“The organism with whom you are conversing uses that name, yes. She is not an individual, however, but an avatar — a vehicle if you will for a single intelligence that simultaneously inhabits this body and those of the other members of our hive.”

“Don’t be stupid. You’ve fallen for some kind of pseudo-religious gobbledegook, that’s all.”

Her jewelled brows lift.

“In spite of her intrinsic human failings, Gillian Dixon was no fool. She knew at once that the phenomenon we refer to as the universal female mind is real, and so did you.”

A single appearance, a single set of opinions, a single purpose.

“Okay, let’s say I accept that there’s something in what you say. Now explain why you need all those silly noises to communicate.”

“You fail to understand, Ruth Pattison. We possess no telepathic abilities. An avatar has her own set of sensory inputs; everything she sees, hears, smells, tastes and touches is unique to her. How could she function otherwise?”

“So you need a way of giving each other factual information, like if the milk has gone sour or a light bulb needs changing. I get that. But what’s with all the clicks and whirrs?”

“They represent syllables culled from a language called Ugur.”

“Ugur? Let me guess, that’s what they speak in Bucovina, right?”

“It originated in Central Asia. Our version was devised by Chrysanthemum von Witzleben, who as you are aware was the founder of the very first hive. It permits us to form expressions that impart the maximum amount of data in the shortest possible time.”

“And you picked it up just like that?”

“Gillian Dixon became proficient in Ugur within three days of her arrival. That is how she knew the incubation process was complete.”

“Your arrival? Weren’t you infected by your daughter?”

“Why do you say that?”

“Louise saw Helen Sutton’s body on the beach. I assumed that’s how the meme got into her brain.”

Gillian shakes her head.

“Helen is the reason we’re here, that is true. But a corpse cannot make converts. Our assimilation into the universal female mind was facilitated by your species.”

I feel the blood drain from my face.

They’re lying about this.

They have to be.

“We were removed from our homes the following night,” Gillian goes on. “Our daughters had seen too much, and had talked to too many of their friends.”

“Where did they take you?” I ask in as steady a voice as I can manage.

“To another country, where we stayed at the home of a kuzkardesh gara named Sorina Dascalu and her three children. Sorina was of English birth, and could therefore–“

“What was she called before her conversion?”

“Sarah-Jane Collingwood.”

I close my eyes and swear under my breath.

They were taken to Bucovina and deliberately exposed to the meme. No wonder Yvette de Monnier struck out on her own. The MoD are doing the cult’s work for them.

Gillian leans closer.

“Choose the right side, Ruth Pattison,” she says softly. “Choose us. Because we are going to win.”

And they are.

For the simple reason that humanity is its own worst enemy.

Our race is doomed by its very nature.

But I won’t become one of these creatures. I’ll slice off my own tits before I let that happen.

“I’m going for some fresh air,” I tell Gillian. “There’s no rule against that, is there?”

Apparently not. She even points me toward the vestibule, where I find a row of pegs upon each of which are hung thin linen jackets — black, of course, to match the regulation dresses. To my relief they all have three hooks at the front, so I can enjoy the luxury of covering my nipples.

Outside, the temperature is rapidly falling. I keep to the paved area near the front door, fearful of twisting an ankle if I stray onto the grass in these heels. After a minute or so the sound of a motor engine drifts from the top of the valley. Someone is heading for an evening at one of the village pubs, or perhaps a chat and a few games of cards at a friend’s, heedless of the peril lurking in the house they’re shortly to pass.

Long may their happy ignorance continue.

Hilary’s voice brings this all too brief spell of solitude to an end.

“It is cold, Ruth Pattison. You should come inside.”

“I’ll be okay,” I assure her, though the jacket wasn’t designed to keep out the chill of a cloudless northern night.

“You need sleep.”

“Yeah, I expect I’ll nod off the second my head touches the pillow.”

I feel her take my arm. I make as if to shrug it away, but her touch is inexplicably comforting.

“We know you are anxious. That is only natural. But the transition is a gradual one. It is not a case of one minute you think you are an individual and the next you do not. The illusion of selfhood does not suddenly disappear. What cease to exist are the mental barriers that prevent you from seeing it for what it is.”

There was no ‘decision’, Ruth. It doesn’t work like that. You don’t go through an epiphany when you lose your individual awareness. It still feels like being you. What’s changed is that your emotional and psychological responses are now identical to those of every other kuzkardesh gara.

“They just pop out of existence, do they?”

“You ought not to make the mistake of thinking there is no scientific basis for any of this.” She reaches into her own jacket and presses a slim paperback into my hand. “Open your mind, Ruth Pattison. If not to us, then to the message in here.”

“I was wondering when we’d get to your sacred texts.”

“It is the truth. Of course it is sacred.”

She walks back to the house. I follow her as far as the door, where there’s enough light for me to peer at the book’s cover. Although the title and author are unfamiliar to me, the publishing company definitely isn’t.

The Oxford University Press? Why are they encouraging this? Come to think of it, why are they being allowed to?

I take the volume up to my room, guessing I won’t be disturbed until I’ve had time to discover this ‘message’ for myself. But before I begin reading, my thoughts return to the tale I was told earlier. The details are unimportant; what matters is that the MoD set up the Sunny Hollow hive with so few restraints on its members’ movement. If they don’t feel threatened by these women, nor should I.

Kicking off my shoes, I hitch up my hem so I can unclip the tops of my stockings, then reconsider. I need to become thoroughly accustomed to these clothes if I’m to feel comfortable in them when I eventually make my escape. I lie back on the bed, raise my knees and let the wide folds of my dress fall where they will.

I open A New Approach to Cultural Evolution with a sense of purpose I didn’t have a few minutes ago. ‘Know your enemy,’ said Sun Tzu in The Art of War. It’s a piece of advice I fully intend to follow.

I haven’t finished the first chapter before I understand why the kuzkardesh gara set such store by this work.

Memes, they’re called, self-replicating units of information that copy themselves and jump from person to person.

Egerton could have been reading directly from the page now in front of me.

Memes.

Viruses of the mind that spread from one brain to another, parasitising the host and turning it into an instrument for the meme’s propagation. Agents of cultural transmission, passed on because of the brain’s predilection for unconscious imitation — a survival mechanism as old as humanity.

If you see a group of people running in a certain direction, the instinct is to join them because they’re almost certain to be fleeing from danger. On the African savannah that probably meant a large predator; those who lacked that automatic response were more likely to be eaten, and consequently fewer of them lived long enough to mate and have children. Natural selection, in the form of fierce, hungry carnivores, has made us intensely susceptible to the replicators that today bombard us from magazines, newspapers, cinema screens, radios and television sets. We can’t stop humming that tune. We’ve simply got to tell that joke. We don’t mean to start talking like the guys on that American cop show, it just slips out.

But memes alone can’t explain why Donna Parker and Louise Dixon, let alone their mothers, chose to follow Sarah-Jane Collingwood’s example and become kuzkardesh gara. There has to be something more going on. Teenage girls tend to copy models, actresses and pop singers, not thirty-four year old mothers of three who go about bald and bare-breasted.

What advantages does the subconscious see in that look? Why is it willing to copy something so utterly abnormal?

I toss the paperback to the floor and swing my legs after it. I reckon it’s well after midnight, and if I don’t at least try to get some sleep I’ll be in no fit state to resist whatever it was that turned Gillian, Hilary and their daughters into the abominations they are today.

I’ve just finished unzipping my dress when I notice a scrap of paper that must have fallen out of the book after I threw it down. I lean forward to lift it from the carpet, frowning as I look at the phrase written on it in a hand eerily reminiscent of Helen Sutton’s.

Siz okde

Now where have I heard those words before?

Okde…

I know what it means. I’m convinced of it.

More unnerving than a déja vu that refuses to fade, more annoying than a fragment of a song whose title just won’t come to mind, those alien syllables resound through my consciousness as I slide into bed and turn off the light.

It means…

It means…

Christ, it’s on the tip of my tongue!

She says I’m gifted.

Gifted. That’s it!

As in talented.

And siz?

Fate has brought you to us for a very special reason.

‘You are gifted.’

That’s the message Hilary was referring to.

And my gift is so important to these women that they’ll do everything in their power to turn me into one of their kind.

I’m going to make sure they have a bloody long wait.

The House In The Hollow: Chapter 3

Author:

Caution:

Audience Rating:

Publication:

Genre:

Character Age:

TG Themes:

TG Elements:

Permission:

|

THE HOUSE IN THE HOLLOW

The sequel to 'Truth Or Consequences'

CHAPTER 3 By Touch the Light I stand up and sweep every item in front of me to the floor. This has gone on long enough. I have to leave now. Fooling these women into thinking I’m coming round to their point of view has become an indulgence I can’t afford. Not when I’ve started hearing voices. |

The sound of someone moving around downstairs rouses me from a dreamless sleep. I sit up, yawn and push a hand back through my hair. It feels even more lank and lifeless than usual, prompting me to make a mental note to ask Janice if she can do something about it, preferably within the next few days.

For a moment I wonder why I’m not wearing pyjamas — then I see the scrap of paper poking from the book on the bedside table, and everything else is reduced to insignificance.

Siz okde.

You are gifted.

I’m in a house occupied by four kuzkardesh gara, and whatever abilities they’ve identified in me are valuable enough to justify keeping me here against my will.

They want me to join their hive.

To add my gift to their collective subconscious.

Imagine living in a street where everyone starts the day with a cup of tea except you, who always have coffee. One morning you walk into the kitchen and instead of coffee you make tea, because that’s what you prefer first thing. You don’t suddenly think of yourself as a tea drinker. You just like tea, the same as your neighbours.

And unless Susan Dwyer was making everything up as she went along, the conversion process is so insidious it could be well underway before I understand what’s happening to me.

Getting away from here would seem to figure reasonably highly on today’s list of things to do.

Emptying my bladder holds the number one spot. I pick up the dress Donna chose for me yesterday, holding it in front of my chest as I pad down to the bathroom. Once I’ve relieved myself I shower — but I don’t lather my hair before I’ve tested the soap on my pubes to make sure it won’t dissolve them like that stuff from Romania did when Kerrie Latimer used it on me. Better safe than sorry.

Better anything than being bald.

As I step from the tub it occurs to me that my clothes and other possessions may well be hidden either in the Dormobile or the barn it’s parked outside. Not that I feel particularly cheered by this sudden insight; without a crowbar to hand they might as well be buried in a strongbox on Pitcairn Island for all the chance I have of getting at them.

I wrap myself in towels, then open the cabinet above the washbasin to take a new toothbrush from the rack.

“Okde,” I mutter as I finish rinsing my mouth. “Siz okde.”

I’ve heard that phrase before. I know I have.

And I suspect it’ll be to my lasting benefit if I can only recall where.

Back in the bedroom, I scowl at the attire I have no choice but to wear until I can recover my own.

You just like tea, the same as your neighbours.

How long would I have to stay here before I came to regard this style of dress as normal? I suspect that’s one of the things I’ll need to watch out for.

I fasten my suspenders with surprising proficiency, but the zip at the back of my dress causes me no end of frustration before I eventually force it to the top. Nor do my shoes, which may be half a size too small — deliberately, no doubt — pinch any the less.

“Bir bolmak hemme.”

I jerk my head to the left at the sound of Gillian’s voice, but there’s no one else in the room. And it seemed much too clear to have come from the landing.

Bir bolmak hemme.

It’s the same language as before. Ugur, or whatever she called it.

As for what that phrase might mean, I don’t think I want to find out.

On the way to the door I catch a glimpse of my reflection in the dressing-table mirror. It’s not an uplifting sight: there are shadows under my eyes, and my hair is sticking up all over. If by some miracle Simon was to make an appearance now, I wouldn’t give much for the chances of him drawing me into his arms once we’d made our escape, let alone treating me to a long, delicious kiss. We might not even get that far — the shape I’m in he’d probably leave me behind for one of the kuzkardesh gara.

Would you believe it, I finally get asked out by a man I’m physically attracted to and something like this has to happen.

Just you wait, Alice Patricia Hodgson. I’ll still be reminding you about this when that kid in your belly is knitting booties for her first grandchild.

My self-esteem has risen slightly once I’ve added a couple of long necklaces to my outfit, so that when I glance down I can see more than just my naked breasts. It nosedives again after I notice how pallid my complexion appears without any foundation or rouge.

They’ve got my cigarettes too, damn them. It’s a good job they haven’t thought of trading fags for locks of hair or I’d be a skinhead by this time tomorrow.

“Bir bolmak hemme…”

There it is again!

Get out of my brain!

I stand up and sweep every item in front of me to the floor. This has gone on long enough.

I have to leave now. Fooling these women into thinking I’m coming round to their point of view has become an indulgence I can’t afford.

Not when I’ve started hearing voices.

I’m getting out of here, and no force on earth can stop me.

Except one.

When I reach the living room, Louise is leaning against the door to the vestibule as she rocks her little son in her arms, whilst Gillian is blocking the entrance to the kitchen. It’s as if they’ve divined my intentions and moved to counter them.

With a good deal of success. I’m no scrawny, underfed waif, but I simply don’t have the strength to push past someone of Gillian’s build. Even her daughter would present me with a problem unless I resorted to violence. And they know full well that as a woman I’d rather shoot myself in the vagina than risk harm coming to a three month old baby.

There’s got to be another way, one that involves tact and guile.

“Salam, Ruth,” smiles Louise, and all at once the solution is staring me in the face.

“Uh, salam,” I reply. “That’s the word they use for ‘hello’ in the Middle East, isn’t it?”

“Ugur is related to Turkish. It also contains elements of Arabic.”

“The meme programs our minds to think in Ugur,” explains Gillian. “We can still speak English, but it is no longer our native tongue.”

“It actually takes quite an effort,” admits Louise.

“The meme scrambles the patterns of neural signals that enable an avatar to use language as a means of communication. After they have been reconfigured she has become a Turcophone, and always will be. She has to rely on her episodic memory if she needs to revert, as we are doing now.”

“I see…” is the response I make — though I don’t, not really. “So what’s ‘baby’?”

“Babek,” answers Hilary, coming in from the dining room.

“That’s easy to remember! Would you mind if I, uh…?”

“Elbetde,” Louise hisses in reply to my unfinished question, her expression translating the term more effectively than any dictionary. She’s telling me of course I can hold him, she trusts me implicitly.

Can she really be that easy to hoodwink?

But as I take Philip from her, the love she feels for him engulfs me, transcending her outlandish appearance and making me viscerally aware of what it must be like to care for the living being I carried in my womb and gave birth to.

“Salam, babek,” I murmur to him, my eyes as adoring as his mother’s. Gillian and Hilary have arrived at my side, their hips pressing lightly against mine. We all start laughing when Philip’s tiny fingers try to shove my beads aside so he can get at my nipple. Donna is here too, her giggles adding to the merriment.

You struggle against us now, Ruth Hansford-Jones, but that which is within you may not be gainsaid.

Susan Dwyer’s warning thunders through my consciousness. This is how the meme operates, latching on to something that’s already inside the victim and changing it to suit its own purposes. It amplifies her desires, at the same time shaping them into the form best equipped to ensure their transmission.

And she hasn’t a clue what’s happening until it’s too late to do anything about it.

I’ve wrenched my mind free from the spell by the time I realise there’s no one between me and the door. I snuggle Philip against my right breast, freeing my left hand to turn the handle. To my immense relief, the jacket I wore yesterday evening is still on its peg.

“I’m going now,” I announce. “I’ll put the baby down when I’m certain I’m not being followed.”

None of the kuzkardesh gara move an inch. Unable to believe my good fortune, I lift the jacket by the collar and punch my arm into the sleeve. Unfastening the Yale lock proves to be a tricky business one-handed, but the taste of liberty is on my tongue and I’m not about to let it trickle from my mouth.

Once I’m outside, I slam the door shut. Depositing Philip on the dew-soaked grass — I don’t suppose he’ll be unattended for more than a moment or two so I have no concerns regarding the child’s safety — I head straight for the road. It’s a tough ascent in high heels; nor is my ability to concentrate on keeping my balance helped by the fact that I’ve eaten practically nothing during the last twenty-four hours.

Breathless and sweating profusely, I reach the top of the path. The Dormobile is still parked outside the barn. It’s locked, of course, and although I’m desperate enough to consider wrapping the sleeve of my jacket around my fist and smashing one of the side windows I’d have more chance of swallowing the engine whole than of starting it without the keys. I waste a few more precious seconds rattling the barn door, already beginning to feel as if I’m fighting for a lost cause.

Somehow I bully myself into thinking more positively. I’m more than twenty miles from home, I have no money and I fear that before long I’ll be ravenously hungry. On the other hand, conditions couldn’t be more favourable: the sunshine has that hazy quality that suggests the weather will soon be overcast and therefore reasonably cool, whilst the recent dry spell means that if I have to cut across country to avoid pursuit I’ll be in no danger of stumbling into a quagmire.

With any luck it won’t come to that.

Glancing behind me every few yards to check that the road is still clear — if one of the kuzkardesh gara comes after me she’ll need to put on her wig and change her make-up, which should give me a bit more time to play with — I walk down to the old railway crossing as fast as my shoes will let me.

The stone cottage beside it looks as devoid of life as the lightning tree in the corner of the field climbing to the wooded ridge on my right. Before I disturb the owner of the white Skoda taking up most of the forecourt I tug at the front of my jacket to test the strength of the hooks holding it closed. The last thing I need is for my tits to pop out while I’m begging to use the phone.

I knock loudly and repeatedly, but to no avail. I’m far from downhearted, however. I can see a farmhouse less than a quarter of a mile ahead, and the entrance to another the same distance along the lane leading from the junction to the beck.

The rumble of a vehicle approaching from the head of the valley has me rushing to open the crossing gate so I can hide round the back of the guards’ van. Although it turns out to be a grey Vauxhall Viva with an unaccompanied male driver, I’m reluctant to return to the road. In my black jacket and dress I’ll be all too easy to spot when my captors eventually start searching for me.

And they might not be the only ones.

I’ve got to disappear, and I’ve got to do it today. I won’t be safe in Northcroft; when the MoD learn that their ploy has failed, they may well opt for a more orthodox means of ensuring I don’t talk. As for where I should pick as a bolt-hole, the further away the better. A croft on a remote Scottish island seems a pretty desirable residence at present.

One thing I don’t have to worry about is supporting myself. Suki was telling the truth when she said I’d been paid handsomely for my work as a government agent. Thanks to the MoD’s munificence I now have nearly five thousand pounds to call on, which I’ve salted away in six separate bank and building society accounts. After a year or so it’s possible that I’d be forced to eke out a living serving pints of Tartan in some Hebridean drinking hovel; then again, I could end up marrying a laird and have servants attending to my every whim.

Will there be anything else, Lady McTavish?

A pot of tea would be nice, Morag. And if you wouldn’t mind asking Cruikshank to walk the collies down to the loch and back?

All that’s conditional on me getting back to the Gladstone by the middle of the afternoon at the very latest, so I can gather my things together and set about laying a false trail to fool people into thinking I’ve gone back down south to deal with a family emergency. I’ll stay in York tonight, then aim for somewhere on the other side of the Pennines to lie low until I’ve liquidated my assets and I’m ready to cross the border.

Fleetwood.

Why not? I’ve never been to Fleetwood. I bet it’s very nice there, on the coast and everything.

It’s not quite the last place anyone would think to look for me, but it’ll be in the top five.

First I need to phone for a cab, and to do that I’ll have to find a house where at least one of the occupants is awake.

I decide to take a chance and follow the trackbed, which is clearly distinguishable from the footpath rising at a gentle but constant gradient for the woods. The railway’s course appears to have run north, away from the foot of the escarpment; there’s every likelihood it’ll pass close to some of the farms and hamlets scattered across the countryside between here and Stokesley. Treading carefully in shoes that hurt more with each step I take, I start out on the next stage in my bid for freedom.

I haven’t walked more than three or four hundred yards before I recognise that I’m rapidly coming to the end of my tether. The mist has thickened, and every lungful of air I inhale seems laden with moisture. Despite the lack of sunshine, the temperature has continued to increase. I daren’t undo my jacket in case I meet someone out for an early morning stroll with his dog; just as annoying, when I push back my fringe, my hand comes away feeling like it’s been through a lump of straw coated in lard.

After about half a mile the trail enters a shallow cutting. This soon opens onto a wide bowl whose sheer, rocky slopes identify it as a disused quarry.

And there the track ends.

I’ve been going the wrong way. All I’ve done is walk down a very long cul-de-sac.

Shitbags!

I sit on one of the smoother boulders strewn around the depression, my fingers immune to the despair clouding my vision as they busy themselves arranging the folds of my dress. Not since I made the discovery that I’d be female for the rest of my life have I felt so low.

But I refuse to cry.

I didn’t then and I won’t now.

“Bir bolmak hemme…”

Not you again!

Can’t you leave me in peace?

I start back for the crossing, mainly because I don’t know what else to do. The footpath still runs parallel to the railway, but I’ll only be able to reach it by crawling up the side of the cutting. And if, as looks likely, it doesn’t skirt the woods but cuts through them to the moorland above, I’ll be faced with not just an exhausting scramble but also a hike of several miles across difficult terrain in poor visibility. With these shoes I’d be risking serious injury and worse.

At the gate I pause, checking to see that the road is clear. The track on the other side of the crossing disappears into a ploughed field. But the line of trees snaking along the valley floor gives me an idea. The dry weather means there won’t have been much run-off; I could follow the channel downstream, perhaps as far as the village. Marginally less irritated at the quirks and caprices of Mother Nature, I jog the short distance to the junction, then stride down the lane in the direction of the beck.

A narrow pathway diverges to the right, threading and dipping through riotous bushes to a precarious wooden footbridge. To my surprise the stream remains fairly vigorous, though the water is nowhere more than a few inches deep. I sit down, take off my shoes and gently lever my body off the slats until my feet are planted in the shallows on either side of the bed. Although my stockings insulate me from the worst of the sudden chill that shoots into my soles, I still let out a high-pitched squeal.

It turns out to be the first of many. With only one hand to fend off the overhanging branches I have to duck beneath in order to prevent their twigs snagging my hair, I find it almost impossible to maintain any sort of balance as I struggle along, one awkward step at a time. The stones and pebbles washed down by the current are jagged enough to tear the nylon protecting my feet to ribbons. Fearing that they’ll soon be lacerating my skin as well, I stoop to put my shoes back on — which only slows my progress more.

Fallen logs, clumps of reeds, banks cancerous with stinging nettles, and now clouds of midges so dense I can scarcely breathe without ingesting dozens of the little blighters…

But it’s the waterfall that defeats me. The drop is only about six feet, yet I can see no way to negotiate it that doesn’t involve jumping — and once I’m down there, I’ll have burned my boats. The sides of the gorge the stream has eroded are almost vertical. Were I to break an ankle I’d be trapped, yelling for help until my voice gave out and starvation or exposure finished me off.

Freedom is a wonderful thing, but it’s of little use to a carcass.