Puddin' River

Author:

Organizational:

Audience Rating:

Taxonomy upgrade extras:

Ancient History

Author:

Blog About:

Chimerae.net

Author:

Not exactly a new story, but it's there:

Sea Changes

A mutant story with animal/human hybrids/Chimerae and beaucoup other stuff. It will be published as a Kindle title and made a part of the BC online store, as soon as I can figure out exactly how to maintain the formatting and a few other technical details involving the limited HTML functionality inherent in the stupid Kindle format.

I particularly like the substitute for the poorly-supported Tooltips which are accessed by clicking in words or phrases highlighted in yellow. In many cases, a fuller explanation can be discovered in the Glossary.

Puddintane

Notable

Author:

Organizational:

Audience Rating:

Taxonomy upgrade extras:

A Uniquely Indian Perspective on Gay Marriage

Author:

Taxonomy upgrade extras:

Read and listen to the story on NPR

Worth the time...

A woman's exploration on the high seas, Jeanne Baret

Author:

Blog About:

Taxonomy upgrade extras:

The first woman to circumnavigate the glove was disguised as a man for the first portion of her journey, and was brutally raped by the crew when she was discovered. It's not a pretty story.

“http://www.npr.org/2010/12/26/132265308/a-female-explorer-discovered-on-the-high-seas”

She was a botanist at the time, and is evidently the actual discoverer of the common ornamental plant, the bougainvillea.

An Inspiring Letter to Anita Bryant

Author:

Taxonomy upgrade extras:

An Open Letter to Anita Bryant

Well worth reading.

Here's Anita Bryant: Anita Bryant's bio on Wikipedia

Note: The article mentions that Florida's ban on Gay and Lesbian adoptions was overturned by the State Supreme Court, but doesn't mention that the State appealed from the ruling and the struggle continues.

Like the poor, the hateful we have always with us.

Puddin'

Ann Rice Comes Out

Author:

Taxonomy upgrade extras:

Well, out of organised religion…

Because of things like this:

Bradley Manning, now Chelsea - Quote without Comment

Author:

Blog About:

Taxonomy upgrade extras:

Quote without Comment

“As I transition into this next phase of my life, I want everyone to know the real me,” Manning said. “I am Chelsea Manning. I am a female. Given the way that I feel, and have felt since childhood, I want to begin hormone therapy as soon as possible.”

Caster Semenya Vindicated -- Free to Compete

Author:

Taxonomy upgrade extras:

Athlete Caster Semenya free to compete

South African athlete Caster Semenya has been given the all-clear to return to competition by the International Association of Athletics Federations.

The 19-year-old world 800m champion has been out of the sport for 11 months after undergoing gender tests.

"The IAAF accepts the conclusion of a panel of medical experts that she can compete with immediate effect," said a statement from the athletics body.

-----------

And about time. Twits.

Common Decency

Author:

Taxonomy upgrade extras:

The California Supreme Court has ruled that a transgender prisoner can sue her guards and the prison system as a whole for their failure to protect her from sexual assault while held in the general male prison population.

The Prison system and the guards had claimed that they had no duty to protect or care for the inmates under their charge.

http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/c/a/2009/02/11/...

Gay Marriage

Author:

Taxonomy upgrade extras:

The recent victory against in the California Superior Court shouldn't be taken for more than what it is, since it's only a regional court, but it's also not trivial. Judge Walker laid out the issues fairly carefully, and the conservative half of the US Supreme Court -- where the case is undoubtedly headed -- has a particular problem in that the case was framed very carefully to draw parallels with the laws prohibiting miscegenation (the mixing of races) that existed in many regions of the USA prior to 1967, when Loving vs. Virginia decided the question in favour of general human rights throughout the USA. He was very specific in finding that the campaign against marriage for all was motivated by animus, not reason, which is a very good thing. In specific detail, his finding of fact are almost a wish list of incontrovertible truths about the hate-filled and bigoted motivations behind the anti-gay movement.

We note with some pleasure that one of the most vicious of the Conservatives on the current court is a Black man married to a White woman, and his vote to allow the public to outlaw anything they don't like would be a vote against his own marriage. He might not care, but his wife ought to.

This is often depicted in the media as a "culture war," but that's a deliberate distortion. It's only the latest faux "issue" in a long series of "white-bigots-only" skirmishes.

The fundamentalist preacher Jerry Falwell (He's the twit who thought that the Teletubbies were gay infiltrators trying to convert American children into flaming sodomites) was still preaching White Supremacy at the time Loving became the law of the land, but soon switched to anti-gay hate mongering:

In 1984, Falwell called the gay-friendly Metropolitan Community Church "a vile and Satanic system" that will "one day be utterly annihilated and there will be a celebration in heaven." Members of these churches, Falwell added, are "brute beasts." Falwell initially denied his statements, offering Jerry Sloan, an MCC minister and gay rights activist $5,000 to prove that he had made them. When Sloan produced a videotape containing footage of Falwell's denunciations, the reverend refused to pay. Only after Sloan sued did Falwell cough up the money.*

Times are changing.

"If Chief Justice Warren and his associates had known God's word and had desired to do the Lord's will, I am quite confident that the 1954 decision would never have been made," Falwell boomed from above his congregation in Lynchburg. "The facilities should be separate. When God has drawn a line of distinction, we should not attempt to cross that line."

Falwell's jeremiad continued: "The true Negro does not want integration.... He realizes his potential is far better among his own race." Falwell went on to announce that integration "will destroy our race eventually. In one northern city," he warned, "a pastor friend of mine tells me that a couple of opposite race live next door to his church as man and wife."*

Pretty soon, real soon now, bigotry of this sort will be intolerable in civilised society.

I can hardly wait.

* From Agent of Intolerance by Max Blumenthal

Interesting SF Book by Melissa Scott

Author:

Taxonomy upgrade extras:

Lambda Literary Award-winning author Melissa Scott often features GLBT characters, but I just ran across The Shadow Man, which explores a world of many genders, most of whom are forced into a binary model. Very interesting.

Iran to allow first transsexual marriage

Author:

Taxonomy upgrade extras:

Woman wins court battle for father's approval to marry schoolfriend who has undergone sex-change operation [FtM]

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2009/sep/11/iran-transexual-...

Laura Jane Grace, Transgender Punk, On Life In Transition

from: National Public Radio

http://www.npr.org/2014/01/19/263503567/laura-jane-grace-transgendered-punk-on-life-in-transition

Love Story

Author:

Taxonomy upgrade extras:

Mainstream Transgender Novel

Author:

Taxonomy upgrade extras:

Prisoners of Gender by John Bushore

A Medieval-Style sword and sorcery novel of magic spells and derring-do.

Used to be free, now free loan for Amazon Prime members, which means it may be free again, but it's only ninety-nine cents in any case.

Puddin'

Note: I've fixed the link.

Oh! It's available in paperback as well, more pricey, though.

My son, the pink boy

Author:

Taxonomy upgrade extras:

Interesting article from Salon.

New and Notable: The Good Lord Bird

Author:

Blog About:

Taxonomy upgrade extras:

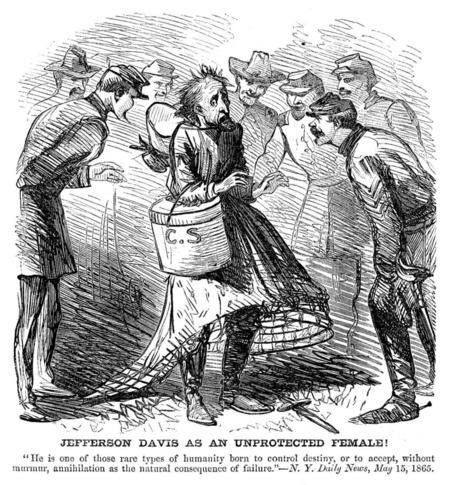

The Good Lord Bird by James McBride

A work of fiction, the protagonist is one Henry Shackleford, a "coloured" man "liberated" by John Brown, the famous Abolitionist and activist. In an odd development, John Brown comes to believe that "Henry," a petite young man, is actually a girl and renames him "Henrietta," which masquerade "Henry" adopts with more or less equanimity.

News isn't always bad

Author:

Taxonomy upgrade extras:

From Stars and Stripes, a newspaper whose audience is primarily men and women in US military service:

http://www.stripes.com/article.asp?section=104&article=68606

Policy revisions approved to allow transfer benefit for same-sex teacher couples

By Travis J. Tritten, Stars and Stripes

Pacific edition, Saturday, March 13, 2010

SASEBO NAVAL BASE, Japan – Same-sex teaching couples are eligible after all for joint job transfers this year at Department of Defense schools, officials said Wednesday.

====================

http://www.stripes.com/article.asp?section=104&article=68652

South Korea bar district offers a safe haven for gay servicemembers

By Ashley Rowland, Stars and Stripes

Pacific edition, Sunday, March 14, 2010

Perhaps of interest...

Author:

Blog About:

Taxonomy upgrade extras:

Hit & Miss - Season One

DVD or BluRay

Available in PAL, NTSC, and BluRay at different price points.

http://www.amazon.com/dp/B00AQYUY9C

Mia is a contract killer with a secret: she's a transgender woman. After a young life where she never quite fitted in, Eddie, an underworld linchpin, took Mia under his wing and created a brilliant assassin. But Mia's life is turned upside down when she receives a letter from her ex, Wendy, who reveals that she's dying from cancer - and that when they were together Mia fathered a son, 11-year-old Ryan. Now Mia is his legal guardian. Travelling to a tiny village in West Yorkshire to see the boy, Mia meets the rest of Wendy's farmhouse clan: 16-year-old Riley, 15-year-old Levi, and 6-year-old Leonie. Hit & Miss follows Mia's attempts to mix her killer instincts with her new maternal ones, in a search for her own identity. A lethal killer at the heart of a troubled family in the middle of nowhere is where the series begins. ...Hit & Miss - Season 1 - 2-DVD Set ( Hit and Miss -- Six part series)

Serious SF/F which explores gender???

Author:

Blog About:

If you have a recommendation about great speculative fiction which explores gender in some way, please send the recommendation to the Tiptree Award jury. They’re reading now for works first published (as a book -- or possibly an e-book) in 2015 only.

http://tiptree.org/recommend-works-for-the-2015-james-tiptre...

James Tiptree, Jr., as you may or may not know, was a woman.

==========

Wikipedia Entry:

James Tiptree, Jr.

Alice B. Sheldon

Born Alice Hastings Bradley

August 24, 1915

Chicago, Illinois, U.S.

Died May 19, 1987 (aged 71)

McLean, Virginia, U.S.

Pen name James Tiptree, Jr.

Raccoona Sheldon

Occupation Artist, intelligence analyst, research psychologist, writer

Nationality American

Education BA, American University

PhD, George Washington U.

Period 1968–1988 (new fiction)[1]

Genre Science fiction

Spouse William Davey (1934–1941)

Huntington D. Sheldon (1945–1987, their deaths)

Relatives Mary Hastings Bradley (mother)

Herbert Edwin Bradley (father)

Alice Bradley Sheldon (August 24, 1915 – May 19, 1987) was an American science fiction author better known as James Tiptree, Jr., a pen name she used from 1967 to her death. From 1974 to 1977 she also used the pen name Raccoona Sheldon. She was most notable for breaking down the barriers between writing perceived as inherently "male" or "female" — it was not publicly known until 1977 that James Tiptree, Jr. was a woman.

Son of Fred Phelps

Author:

Taxonomy upgrade extras:

Story from Xtra! Gay and Lesbian News in Canada

Fred Phelps' son has a new job: promoting atheism and battling homophobia.

NEWS: Son of 'God Hates Fags' preacher likes Lady Gaga and wants more gay bars in Calgary

by Neil McKinnon

National

Thursday, July 22, 2010

Suicide and Suicidal Ideations

Forums:

Taxonomy upgrade extras:

Suicide and Suicidal Ideations

Suicide, the threat of suicide and suicidal depression are chronic problems among transgendered folk and other sexual minorities. Suicide is about emotional pain. Emotional pain can be managed and relieved with skilled assistance. Anyone who has persistent or recurrent thoughts of suicide needs to know that their lives are valuable, that there are people who care about them, and that there are people who can help, are trained to give timely assistance, and have resources on call.

If you, or someone you know, is in immediate danger because of thoughts of suicide, please call 911, the US National Emergency Number now. You will be helped, but you have to call.

If you're not in the USA, you can call your local emergency number, or one of the short selection below.

In the USA, There are two national hotlines, plus every state and many communities have local hotlines as well. A call to directory assistance or the local emergency number will put one into contact with effective help very quickly if a number isn't readily available.

The following numbers are available seven days a week and twenty-four hours a day in the USA.

Suicide.org - Suicide Prevention, Awareness, and Support

http://www.suicide.org/

1-800-SUICIDE

1-800-784-2433

National Suicide Prevention Lifeline

http://www.suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

1-800-273-TALK

1-800-273-8255

Deaf TTY Hotline:

1-800-799-4TTY

1-800-799-4889

In the UK and the Republic of Ireland

Samaritans: http://www.samaritans.org/

UK: 08457 90 90 90

ROI: 1850 60 90 90

In Australia: http://www.lifeline.org.au/

Telephone: 13 11 14

In New Zealand: http://www.lifeline.org.nz/

Telephone: 0800 111 777 (Christchurch)

Telephone: 0800 543 354 (National)

All Other Countries

Befrienders Worldwide http://www.befrienders.org/

They offer an extensive list of national and local helplines by country.

For everyone, even if you can foresee no possible need for one of these numbers on your own, it might be thoughtful to enter one of the local numbers on your cellphone, or write one down on a scrap of paper in your billfold or wallet. Life is long -- or should be -- and you may stumble upon someone who needs it.

TG Kindle Title download on Amazon

Author:

Taxonomy upgrade extras:

The Velvet Closet [Kindle Edition]

by Chandra Borden

Note: This title is no longer free.

There's a Good Tradition

Author:

Taxonomy upgrade extras:

Transsexual wins $500,000 lawsuit

Author:

Taxonomy upgrade extras:

Interesting piece originally in the SF Chronicle:

Article reprinted in the Pink Pages

A federal judge has awarded a former Army Special Forces commander nearly $500,000 because she was rejected from a job at the Library of Congress while transitioning from a man to a woman....

etc.

Turnabout Film on Cable

Author:

Blog About:

Turnabout, the 1940 Body-Swapping film from the original novel by Thorne Smith, is scheduled on Turner Classic Movies (TCM) at 5:00am Pacific Time tomorrow morning, if anyone is interested and has Cable or Satellite access to the channel. People who live in other timezones will have to apply the appropriate timezone arithmetic.

It’s not the greatest film, but it’s not terrible either, and (like most of his other works) is fairly droll.

If one lives in Europe, the book is out of copyright (published in 1931) and is available at the Forgotten Futures website, along with many of his other works.

A precís of the plot follows:

Tim and Sally Willows are vaguely dissatisfied with their lives, and are bickering about whose rôle in life is easier when they annoy a pagan idol from Egypt, one Mr. Ram, who swaps their bodies out of a certain malicious sense of humour. Tim is forced to cope with the complications of his wife’s life, including the amourous attentions of the local cad, whilst Sally has to manage Tim’s job as an advertising executive. Complications ensue, including the completely unplanned pregnancy of Tim (as Sally) who winds up giving birth to their child.

US House passes inclusive hate crimes bill

Author:

Taxonomy upgrade extras:

U.S. House Passes Inclusive Hate Crimes Bill

Updates to Federal Law Would Strengthen Law Enforcement Ability to Investigate, Prosecute Hate Crimes.

4/29/2009

Washington — The Human Rights Campaign — the nation’s largest lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender civil rights organization — hailed today’s bipartisan vote of 249-175 in the U.S. House passing the Local Law Enforcement Hate Crimes Prevention Act, also known in the U.S. Senate as the Matthew Shepard Act.

“All Americans are one step closer to protection from hate violence thanks to today’s vote,” said Human Rights Campaign President Joe Solmonese. “Hate crimes are a scourge on our communities and it’s time we give law enforcement the tools they need to combat this serious problem.”

“No one should face violence simply because of who they are,” said Judy Shepard, executive director of the Matthew Shepard Foundation. “This bill is a critical step to erasing the hate that has devastated far too many families.”

Yesterday the White House released a statement from President Obama calling for passage in the House and urging the Senate to follow with swift action. Along with the President, more than 300 law enforcement, civil rights and religious organizations support the bill.

“The Senate should heed the President’s leadership and quickly pass the Matthew Shepard Act,” said Solmonese. “After more than ten years and tens of thousands of victims, there should be no delay in passing this bill into law.”

This is the eighth successful vote on a federal hate crimes bill which — following a veto threat from former President Bush — died in the last Congress.

“Fair-minded leaders in Congress have for years stood strong against lies about the bill and we are grateful for their efforts,” continued Solmonese. “The leadership of Speaker Pelosi, Majority Leader Hoyer and Majority Whip Clyburn as well as Reps. Conyers, Kirk, Baldwin, Frank, and Polis made this incredible victory possible.”

Working in coalition with the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights, the Human Rights Campaign mobilized its members to support the bill. The website www.FightHateNow.org gives users opportunities to contact their member of Congress, watch video testimonials on hate crimes and learn the truth about the legislation. The site will continue as a clearinghouse for information leading up to Senate action.

The LLEHCPA gives the Justice Department the power to investigate and prosecute bias-motivated violence where the perpetrator has selected the victim because of the person's actual or perceived race, color, religion, national origin, gender, sexual orientation, gender identity or disability. It provides the Justice Department with the ability to aid state and local jurisdictions either by lending assistance or, where local authorities are unwilling or unable, by taking the lead in investigations and prosecutions of violent crime resulting in death or serious bodily injury that were motivated by bias. It also makes grants available to state and local communities to combat violent crimes committed by juveniles, train law enforcement officers, or to assist in state and local investigations and prosecutions of bias motivated crimes.

UPDATE: The Matthew Shepard Act was, in fact, signed by President Obama on October 28, 2009. Whilst not perfect, it's a very good start.

Wikipedia Article on the Matthew Shepard Act

Web Communities

Author:

Taxonomy upgrade extras:

A web community is like any other community, and needs police.

Just as people become tired and distant from their own local communities when vandals are allowed to freely trash the buildings, cover walls with vulgar or hateful messages, and play music loud enough to destroy eardrums, people demand a minimum level of civility in the places they spend any time in.

Since ordinary users can't perform a "citizen's arrest" of vandals, they are dependent on the "cop on the beat" to control things on their behalf. In most cases, this is a site admin, or a localy-appointed monitor if the community is large enough, and the job is largely thankless.

Ignoring the policing part of creating a community will inevitably destroy it, as there are always a few putzes around, who will quickly mess up the neighbourhood if not controlled. Messy neighbourhoods, hate-filled neighbourhoods, discourage loitering, so people move on quickly.

Cheers,

Puddin'

On Writing

Author:

Organizational:

Audience Rating:

"Said Bookisms are boring," she snarled.

Author:

Taxonomy upgrade extras:

"Said Bookisms are boring," she snarled.

by Puddin'

For reasons of my own, I have a treasured copy of The Said Book by J.I. Rodale and Mabel E. Mulock. While I've never actually studied it, I think of it from time to time because it's so infamous amongst writers that it has it's own catch phrase, a "said bookism." Go ahead, google it, you'll see.

It's so familiar that one often sees it abbreviated to the simpler "bookism," what might be called a euphemism for a particular style of purple prose in which the author elaborately avoids the use of the word "said" in favour of other, seemingly more descriptive verbs.

--- she laughed.

--- she cried.

--- she sighed.

--- she expostulated.

--- she lucubrated

The trouble with these verbs is that the first three aren't actually speech, and we must presume that they take place either before or after an act of speech, so they're really leaving the most cogent information being conveyed — the simple identity of the speaker — by the wayside and then haring off on a more-or-less lovely meander. The next two are just elaborate verbs that may or may not be easy for a reader to understand. They get in the way of understanding the story, and might as well be Sanskrit for many people.

These "descriptive" verbs aren't actually all that descriptive, don't serve their intended purpose of breaking up long and terminally-boring stretches of unleavened dialogue with evocative descriptions of the scene or the behaviour of the speaker, and are almost certain, in real life, to cause an acquisitions editor to toss a manuscript containing more than one or two per chapter back into the slush pile, if not to hurl it against the wall in disgust.

The advantage of "said" is that it's nearly invisible, nearly as invisible as the word "the," and takes up almost the perfect amount of visual dwell time to correspond to a natural pause in speech, like a comma. "Asked," although technically a "said bookism," is usually not counted amongst them, but the pair of these words is almost always sufficient for dialogue spoken without too much ambiguity or sarcasm.

Here's Hemingway's short story, Hills Like White Elephants as an example of the depths of subtlety possible, even within the span of these two simple verbs:

Note that the attributive verbs used are "said" and "asked," and that even these are sparsely distributed. Dialogue is quite often understood from context, and the flatness, sometimes anguished desperation, of the woman's speech lies hidden under the bland surface of the written dialogue like a strong current under the placid surface of a river.

Hemingway was a proponent of not saying everything possible, and of deliberately leaving some things unsaid, because the reader would become aware of them despite their seeming invisibility, so we quickly figure out that the "operation" in Hills Like White Elephants is actually an abortion, that the man is a fatuous and irresponsible fool, and that the whole scene is as dreary and oppressive as the flat landscape and heat.

He said once that he wrote one page of masterpiece for ninety-one pages of shit, and that he tried to put the shit in the wastebasket, an excellent motto for the aspiring writer.

Dialogue can indeed become boring, but the best solution is to introduce more evocative prose, not a single verb.

Instead of " 'Fred!' she cried," one might try "She fell sobbing to the ground, lifted up her face toward her husband, and slowly wiped the tears from her eyes. 'Fred!' "

Raiders of the Lost Ark, the movie, doesn't start with a narrative description of the dubious career of Indiana Jones and then talk about a fabled treasure he might like to look for whilst everyone is sitting around a shabby table in Podunk, Oklahoma. It starts with a cliffhanging episode of tension and catharsis which *shows* us what Indiana is like before the first line of dialogue is spoken.

Dialogue is easy, l'esprit d'escalier, the sort of thing one has running through one's head at times, "...and then I should have said...." Capturing the soul of a moment, a series of moments, picking and choosing which moments to describe --- possibly including dialogue --- and then retain and which to toss away is hard.

Here's an excellent discussion of Said Bookisms:

Cheers,

Puddin'

----------------------------

The first draft of anything is shit.

--- Ernest Hemingway

A Generous Baker's Dozen: Writing Guides by Women (Mostly)

Author:

Blog About:

Taxonomy upgrade extras:

A Generous Baker’s Dozen: Writing Guides by Women (Mostly)

in no particular order

- The Writing of Fiction by Edith Wharton

- Great book by the first woman to win the Pulizter Prize. Not only that, she has a chapter on Marcel Proust.

- Negotiating With the Dead: A Writer on Writing by Margaret Atwood

- The compilation of a series of lectures, Margaret Atwood is seriously literate, which every writer should strive to be.

- Steering the Craft: Exercises and Discussions on Story Writing for the Lone Navigator or the Mutinous Crew by Ursula K. Le Guin

- Ursula Le Guin. Enough said.

- Writing from the Body: For Writers, Artists and Dreamers Who Long to Free Their Voice by Ceci Miller-Kritsberg and John Lee

- An interesting approach, perhaps a bit reminiscent of Natalie Goldberg, but he runs a very popular writing workshop. Very focused.

- The Scene Book: A Primer for the Fiction Writer by Sandra Scofield

- This is a nitty-gritty book that takes a very detailed approach to creating the ‘scenes’ that chapters and books are made of.

- Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life by Anne Lamott

- This is a book that focuses on struggle. The title comes from an experience faced by her brother as a child, the need to write a report on birds that he’d been procastinating about until the last minute. Their father told him, ‘Just take it bird by bird….’

- One Year to a Writing Life: Twelve Lessons to Deepen Every Writer’s Art and Craft by Susan M. Tiberghien

- If you like Carl Jung, you’ll love Susan Tiberghein. Her excercise are something like a quick(ish) psychoanalitic treatment series.

- Writing Down the Bones: Freeing the Writer Within by Natalie Goldberg

- This is another deeply philosophical book inspired by Zen meditation. She has several books out, all of them excellent, in my opinion.

- Silences by Tillie Olsen

- A classic work for women on writing.

- Writing Fiction: A Guide to Narrative Craft by Elizabeth Stuckey-French and Janet Burroway

- The classic textbook used in many writing classes. Since it’s essentially a college text, it’s terribly expensive unless you find it in an out-of-the-way used bookshop, if things like that still exist in your neighbourhood.

- 20 Master Plots and How to Build Them by Ronald B. Tobias

- For those who like ‘cookbooks’ rather more than pure creativity, Mr Tobias gives one a simple precis. Fill in the blanks, season to taste.

- The Situation and the Story: The Art of Personal Narrative by Vivian Gornick

- Great book, but focuses more on nonfiction and essays.

- On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft by Stephen King

- Okay, speaking of personal narratives, this one’s definitely not by a woman, but it’s compelling in spite of that. I don’t particularly like his fiction books, as I’m not at all fond of the horror genre, but this, this book is different.

- Writing the Breakout Novel by Donald Maas

- This one is actually two books, the book proper and its workbook. The author is a literary agent, so perhaps knows a bit about what it takes to get one’s masterpiece published. Reading is all very well, but practice makes perfect.

- Your favourite title(s) by your favourite author(s)

- This/these is/are perhaps the most important book (or books) to reference. Write what you love, not what you think will sell. Emulate the authors whose books moved you, the books that made you want to write. Writing is an apprenticeship, when push comes to shove, and studying the work of a master, someone whose books you desperately want your work to resemble, is the most personal lesson you can learn. With every sentence, think about how (fill in the blank) might handle the scene, the dialog, the action. Seek out examples in his or her work, and see how they work.

Adding Pictures to Your Stories

Author:

Taxonomy upgrade extras:

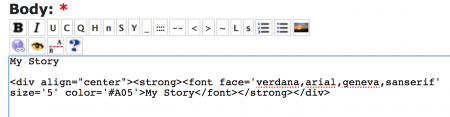

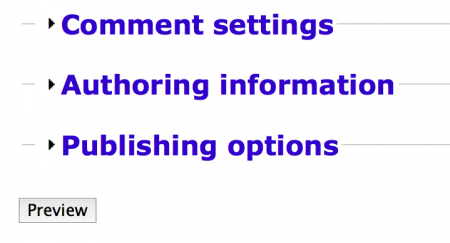

The key to adding pictures is one of the buttons at the top of your edit box. It looks like this:

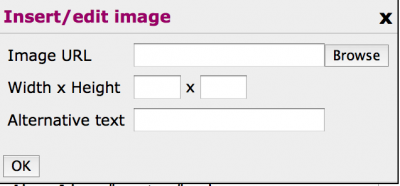

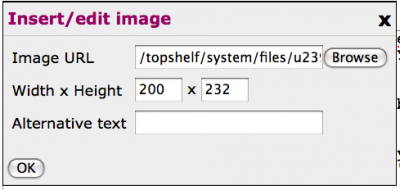

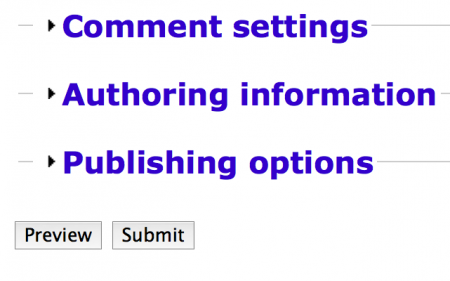

If you click on it, a little box will pop up that looks like this:

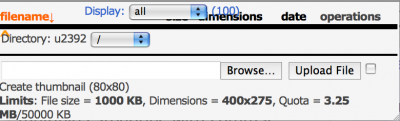

This new box allows you to do one of two things, you can enter the URL of a picture from the web in the field labelled Image URL*, or you can click on the ‘Browse’ button to either select preloaded pictures from your picture directory (if you've already loaded some) or you can click on yet another ‘Browse’ button at the bottom on the resulting selection box to choose a picture off your own hard disk. I shrank the size of this box down to almost nothing in the image below, so you can't see most of the box yet. Ignore the top of the box entirely.

To load something from your hard disk, you'll have to look at the bottom of this box. There are two important buttons, first the ‘Browse’ button, which will pop up a directory listing, from which you'll select your picture. Here's what they both look like:

Once you select the picture, click on the second button, the ‘Upload File’ button, or it will stay on your hard disk and never be copied to your picture directory on Big Closet.

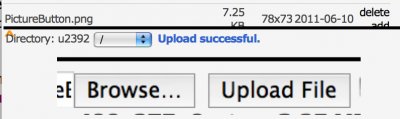

Eventually, you'll see the screen change so that looks like this:

Note that your picture will be displayed, so you can easily see if you got the right image when you selected the original file.

It might have another "success" message, which means that the picture was too big, and had to be scaled to fit the maximum allowed size. Here's what it looks like:

This is a good thing, because it's courteous to readers who don't happen to have a T1 line run to their home or office. It's a good thing for you as well, because you won't have to fiddle with graphics editing programmes to tweak your pictures.

Now, there's only one step left; you have to look at the top of the box we ignored before and choose the picture you've just uploaded from the user directory listing shown at the top of your screen. Don't select ‘Delete.’ Select ‘Add.’ The same ‘Insert/Edit’ box will pop up that we saw at the start of our little journey, except this time it will have the URL box filled in. Now click the ‘OK’ button. All the fancy HTML text needed to insert a picture is now inside your text.

You can use the ‘Preview’ button at the bottom of the Edit screen to see how it looks.

Voila!

Puddin'

* Taking pictures directly from the web isn't usually a good idea. In the first place, a lot of pictures on the Web are a lot larger than many Big Closet readers can comfortably download, if they have slow connections to the Internet, and it causes Erin's server to access the Web every time a Big Closet reader views your story or blog entry, which slows things down for everyone. URL accesses take time. Time is money.

Author Names

Author:

Taxonomy upgrade extras:

I've noticed quite a few stories with no titles and/or author names attached.

There may be a title vaguely associated with the story taken from the file name, but those two things are not necessarily the same thing, as you can see with this very blog.

Likewise, there may be a posting name associated with the story, but again, those things may have little or nothing to do with the author.

It's fairly important, if one wants at some point to assert a copyright to one's words, to have something like a real name or pseudonym that one can claim in the actual story display page.

Titles cannot be copyrighted, so a hundred authors can all write books called War and Peace and have no claim against each other.

Likewise, most names are not unique, so a hundred John Smiths can write a hundred novels, all named War and Peace, but you start to see the difficulty, which is why most writers come up with a name that is unique within their own particular genre, and there's a sort of tacit agreement not to tread on each other's toes in this regard.

If one becomes famous (even a little famous) in a particular genre, trademark law becomes an issue, so one might face problems if your real name was Anne Rice and you wanted to write Vampire or Witch novels, unless you happen to be the same Anne Rice who wrote The Vampire Lestat and made the name famous to begin with.

With really famous names, you probably don't want to use the name at all, even if you were given the name at birth, as many people named McDonald have discovered to their cost when they tried to open a restaurant named after themselves.

It's a reasonable precaution, then, to make sure that a reasonable story name and a reasonable author name are included on the page. Most authors are proud enough of their work that they insist upon it, but publishing with no name at all is an invitation to theft.

There are handy little buttons at the top of the story Body: entry box that make it easy to enter a title and an author, the [C] button (fourth from the right) and the [H] button (fifth from the right), which centre and emphasise selected text respectively.

They can be used sequentially on the same text or any single selection.

Right-Justified Title and Author

The Vampire Fred

by Edna Farkle

Centred Title and Author

By the way, when you look at the shelves in any real bookstore, you'll notice close to zero "author names" that look like 'Romeo472.' Part of trying to be a real author is looking like a human being, not a robot with a serial number attached to a model name. Mind you, there is a real book named Ralph-124C 41+, by Hugo Gernsback, but this describes the naming conventions of a dehumanising civilisation of the future, which Ralph himself eventually transcends. The book itself is written very badly, but it's simultaneously one of the most important works of Science Fiction ever written, a very pretty paradox.

Cutting Loose

Author:

Taxonomy upgrade extras:

Cutting Loose

by Puddin

Loose is pronounced with an "S" sound. One has loose change. One looses an arrow, or loosens a bolt with a spanner. One is at loose ends. One cuts loose a kite string.

Lose is pronounced with a "Z" sound. One loses one's mind, or one's way.

Usually, one doubles an "O" to make a long "OO" sound, but in this particular case the vowel sound is much the same and the doubling marks a change in the consonant. The double "O" in "loose" does make a difference, because it keeps its long sound when you fiddle with it, whereas "lose" turns to "lost" and changes both sounds at the same time.

You can always tell the difference between "lose" and "loose" if you say the word aloud.

She let her dog run loose, which is a sure way to lose it.

I tightened the loose nut on the axle, because I didn't want to lose it at high speed and crash.

If one loses weight, one's trousers may become loose. If one's trousers become too loose, one may lose them.

Editing Humour

Author:

Blog About:

Taxonomy upgrade extras:

English Punctuation Skills

Author:

Taxonomy upgrade extras:

English Punctuation Skills

by Puddin'

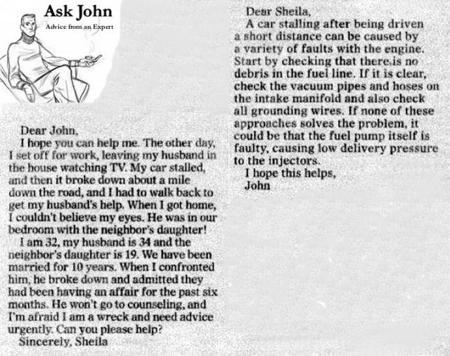

The Importance of Correct Punctuation

Author Unknown

Dear John:

I want a man who knows what love is all about. You are generous, kind, thoughtful. People who are not like you admit to being useless and inferior. You have ruined me for other men. I yearn for you. I have no feelings whatsoever when we're apart. I can be forever happy--will you let me be yours?

Gloria

-----------

Dear John:

I want a man who knows what love is. All about you are generous, kind, thoughtful people, who are not like you. Admit to being useless and inferior. You have ruined me. For other men, I yearn. For you, I have no feelings whatsoever. When we're apart, I can be forever happy. Will you let me be?

Yours,

Gloria

English Spelling Skills

Author:

Taxonomy upgrade extras:

English Spelling Skills

by Puddin'

No less a respected figure than Mark Twain, notable American author and raconteur, has offered a coherent plan for the simplification of English spelling such that, in a few short years, everyone will be fully literate and perfectly capable of spelling to a level that any English speaker could easily win at least local spelling bees.

-----------

A Plan for the Improvement of English Spelling

by Mark Twain

For example, in Year 1 that useless letter "c" would be dropped to be replased either by "k" or "s", and likewise "x" would no longer be part of the alphabet. The only kase in which "c" would be retained would be the "ch" formation, which will be dealt with later. Year 2 might reform "w" spelling, so that "which" and "one" would take the same konsonant, wile Year 3 might well abolish "y" replasing it with "i" and Iear 4 might fiks the "g/j" anomali wonse and for all.

Jenerally, then, the improvement would kontinue iear bai iear with Iear 5 doing awai with useless double konsonants, and Iears 6-12 or so modifaiing vowlz and the rimeining voist and unvoist konsonants. Bai Iear 15 or sou, it wud fainali bi posibl tu meik ius ov thi ridandant letez "c", "y" and "x" -- bai now jast a memori in the maindz ov ould doderez -- tu riplais "ch", "sh", and "th" rispektivli.

Fainali, xen, aafte sam 20 iers ov orxogrefkl riform, wi wud hev a lojikl, kohirnt speling in ius xrewawt xe Ingliy-spiking werld.

Giggles Seen as Harmful

Author:

Taxonomy upgrade extras:

Giggles Seen as Harmful

by Puddin'

There seems to be a misconception --- or perhaps a folk belief --- among many authors on this and other "transgender" sites that "giggle" means "to laugh in a girlish or womanly manner," and that using the word regularly, perhaps even to excess, makes a story more "feminine," but this isn't quite true.

Giggle - Verb

1. to laugh in a silly, often high-pitched way, esp. with short, repeated gasps and titters, as from juvenile or ill-concealed amusement or nervous embarrassment. (Random House Unabridged Dictionary © Random House, Inc. 2006)

The word is actually somewhat contemptuous, as you can guess from this definition, and in practice is quite often used in a snide and deliberately misogynistic way, implying that the females so described are noticeably less clever, capable, or mature than males are, and may even partake of the disgusting male "bimbo" fantasy.

There are situations in which this condescending and unflattering description might be accurate, but both young girls and women usually chuckle, laugh, snicker, or guffaw like other human beings, albeit usually in a higher vocal register. The word "giggle," like "cackle," "natter," "prattle," "titter," "chatter," and other contemptuous words most usually applied by men to women and/or homosexual men, does not reliably convey this latter meaning and, when almost every female expression of amusement is so depicted, it's more than a little tiresome and offensive.

One hardly ever hears a woman use the word, except as a noun, and possibly a joke, usually expressing (wryly or otherwise) a somewhat negative or hostile view of male attitudes toward women and girls, although this latter point is often a bit too subtle for most men to notice.

In fact, in stories purportedly being written a woman's viewpoint, with a woman as author, its cliched presence usually betrays an underlying masculine viewpoint, which tends in this culture to be misogynistic by default, and so is distinctly "unfeminine," despite its fetishistic presence in some "transgender" writing.

"Laugh" is the basic word, and should always be considered before other options. "Giggle" is not the female default, unless you mean to simultaneously imply stupid or immature behaviour and/or inappropriate emotions.

In the Batman stories, the Joker often "giggles" because he is psychotic, not because he's secretly a woman. Renfield, not generally thought of as transgendered, "giggles" in the Dracula novels and movies for the same reason, but insanity is not usually a reasonable opinion of the customary mental state or behaviour of women and girls.

Cheers,

Puddin'

Horizontals Rule

Author:

Taxonomy upgrade extras:

Horizontals Rule

by Puddin'

Although they look very tidy, they're only decorative elements in HTML, but people often use them as scene separators, a burden they're not meant to carry. Because they have no semantic meaning, they're exactly equivalent to nothing in the syntax of the web.

Amongst the pernicious effects of this logical invisibility, they're inaccessible to many people with vision difficulties, and the many people who archive their favourite stories will be discommoded as well, because the scene breaks will disappear from their purview, whilst the story turns into one endless scene mash-up.

Tricks of the Trade

There are three primary strategies often used in stories to signal scene changes, textual, visual, and some combination of both:

Meanwhile, back at the ranch, Dusty was packing up his bedroll for the long trail ahead…

…is a textual indication. It's a traditional storytelling tool, and needs no special equipment other than an author's voice or pen. Although this particular technique is very terse, it also depends upon the audience knowing that a ranch exists, and is familiar enough with it that they'll have an instant picture of it in their minds. It's often wise to add a few more bits of detail, because every scene should have an immediate presence and reality. It's almost always a mistake to transition between scenes when one scene ends with dialogue and the next begins with dialogue.

"O! what a rogue and peasant slave am I," said Hamlet.

-o~O~o-

"O most pernicious woman! O, villain, villain, smiling, damned villain!" said Hamlet

Even with enough space left to mark a scene change, and decorative indications, the lack of textual confirmation makes the continuity confusing, and may even lead to inadvertent jokes, because the reader can easily lose the context.

Another Trick

Chapter Seven

…is another textual indication. In the verbal storytelling tradition, it might correspond to a musical interlude or even an interval between one night's entertainment and the next. Ideally, a chapter indicates a logical break in the continuity of the story. A "cliffhanger" has been presented, an exciting revelation has been made, or something important has happened. At the end of a chapter, the reader should be very anxious to turn the page, and it ought to mark a significant milestone in the progress of the story.

Because they're so important, stories quite often add special indications as well, printing the chapter title in Bold Face, Larger, SMALL CAPS, and — most importantly — putting extra space between the end of one scene and the next, or even an extra page between one chapter and the next.

White space is very important on the printed page. It helps us see what's important, because our eyes are very finely attuned to variations in brightness and colour. We can see the glint of a panther's eyes in the forest, or the slight variation in the colour of the vegetation that masks a hidden mire. If we didn't have these skills, we would by now be a footnote in some other creature's paleontology books.

Printers have long made use of space to create a pleasing page that's easy for the eye to follow. The reason we hate sentences and words in ALL CAPITAL LETTERS is that there's not enough white space around them. Capital letters are square and ugly, so quickly cloy when there are too many of them. Normal letters go up and down as you read along the line, with ascenders and descenders that might remind you of a wooded meadow, if you could separate your literacy from your aesthetic sensibilities for a moment. Every human writing system uses similar tricks of light and shadow to make characters unique, although some are better at this task than others.

Squint your eyes together for a bit, until the letters on this page start to blur. You'll start to see organic patterns in the blocks of words, rivulets of white space running down through the paragraphs like the pale roots of trees, variations in the horizontal stretch of the lines that make them look a little like earthworms with rings and undulations them make them wriggle with life.

We humans enjoy life. We see living faces in clouds, the outline of dogs or horses in craggy rocks, we recreate life in paintings and drawings using smeared pigments or graphite dust, we make our words live by the way we place them on the page.

In traditional typography, empty space breaks up the page and gives it what typographers call "colour," although the "colour" may be only shades of grey, so it was and is traditional to celebrate that living space by filling the precious emptiness with one or more decorative elements, in older books, usually somewhat elaborate, often explicitly floral or vegetative, and in more modern books simple rules, but the primary indication of the scene break is the extra space, not the decoration meant only to embellish it.

If you glance to your upper right (you may have to scroll a bit), or follow the link, you can see more about using empty space in my essay on Paragraphs.

Poking a horizontal rule between two paragraphs does nothing, unless you create the space that rule is meant to decorate, and in fact the rule itself obscures the white space through partially filling it with typographical colour.

Pellentesque nibh felis, eleifend id, commodo in, interdum vitae, leo. Praesent eu elit. Ut eu ligula. Class aptent taciti sociosqu ad litora torquent per conubia nostra, per inceptos hymenaeos.

Maecenas elementum augue nec nisl. Proin auctor lorem at nibh. Curabitur nulla purus, feugiat id, elementum in, lobortis quis, pede. Vivamus sodales adipiscing sapien.

On BC, you create that extra space using one of the buttons above the edit box — the ninth button — the non-break space, labelled with an underscore: _ . You can also enter it directly:

If you place a non-break space on a line by itself, the BC rendering mechanism treats it as if it were an empty paragraph, so leaves a bit of extra space between one line and the next. If you don't use this trick, multiple empty lines will be collapsed into one empty line and your scene break will logically disappear, even if you add a horizontal rule. Here's a similar example with more whitespace added using a non-break space:

Vestibulum posuere nulla eget wisi. Integer volutpat ligula eget enim. Suspendisse vitae arcu. Quisque pellentesque. Nullam consequat, sem vitae rhoncus tristique, mauris nulla fermentum est, bibendum ullamcorper sapien magna et quam. Sed dapibus vehicula odio. Proin bibendum gravida nisl.

Fusce lorem. Phasellus sagittis, nulla in hendrerit laoreet, libero lacus feugiat urna, eget hendrerit pede magna vitae lorem. Praesent mauris.

In the above case, I added even more whitespace by adding a width attribute to the horizontal rule: <hr width="50%" />

The Original Tricks

![]()

he old typographical rules for print publications used actual characters instead of lines, quite often stylised vegetation like ivy leaves (the Hedera - ☙ - sometimes improperly labelled a "floral heart"), other "pi" characters, or especially-cast decorative rules. You've seen them, I'm sure. The connection to living vegetation was so strong that they were collectively called "fleurons," from the Old French word for "flower." The stories recently posted by The Professor use especially florid examples, large graphics like this:

but simpler graphics are possible:

❀ ❀ ❀

~❦~❦~❦~

₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪

The last example uses a particularly pretty character for texts involving ancient times, although it's a modern symbol, the Sheqel symbol ( ₪ ), entered (one at a time) like this: ₪

The Catch

![]()

The problem with all these decorative imitations of a printed page, however, is that the Web allows authors to specify the actual construction of a page in very flexible ways. To properly use a horizontal rule, or any decorative separation, they should really be combined with semantic elements meant to carve documents into relevant bits, the "Heading" elements: H1-H6

Like this:

<H1>My Life with George</H1>

<H2>by Bess</H2>

<H3>In the Forest</H3>

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet. Suspendisse vestibulum dignissim quam. Integer vel augue. Phasellus nulla purus, interdum ac, venenatis non, varius rutrum, leo. Pellentesque habitant morbi tristique senectus et netus et malesuada fames ac turpis egestas.

<H4>☙X❦X❧</H4>

Duis a eros. Class aptent taciti sociosqu ad litora torquent per conubia nostra, per inceptos hymenaeos. Fusce magna mi, porttitor quis, convallis eget, sodales ac, urna. Phasellus luctus venenatis magna. Vivamus eget lacus. Nunc tincidunt convallis tortor. Duis eros mi, dictum vel, fringilla sit amet, fermentum id, sem.

☙X❦X❧ (H4)

Phasellus nunc enim, faucibus ut, laoreet in, consequat id, metus. Vivamus dignissim. Cras lobortis tempor velit. Phasellus nec diam ac nisl lacinia tristique. Nullam nec metus id mi dictum dignissim. Nullam quis wisi non sem lobortis condimentum. Phasellus pulvinar, nulla non aliquam eleifend, tortor wisi scelerisque felis, in sollicitudin arcu ante lacinia leo.

☙X❦X❧ (H4)

Blah blah blah...

The End (H4)

Of course the "headings" don't have to be words, and can be centred or decorated however one desires, but it will automatically generate a real structure for the document that most web-based tools for the vision-impaired can decode and present in accessible form.

Accessibility

If you use Firefox, you can actually see and make use of these features to help navigate through stories, if the author has included semantic elements. As a trial, start up Firefox — if you're not using it already — and select Accessibility from the top menu bar. Then select through Navigation and then Headings to pop up a navigation box for this page.

Because of the method used to display stories, it will say that there's an error on the page, because there are too many <H1> elements on the page. You can ignore this.

Look down the list in the navigation box and select the line that says: <H1>My Life with George</H1>

You'll notice that the main screen will adjust itself so that this element is highlighted and visible on the screen. You can select any of the other semantic elements and the same thing will happen.

Think of how handy this might be in many situations…

If you were blind and using the JAWS screen reader, this completely non-visual browser would speak the semantic elements aloud, and you could jump to different portions of the document by reacting when a particular element is read by pressing a key. Then, the browser would read the text following that element aloud. With practice, a blind user can navigate through a well-formatted document almost as quickly as a sighted user can.

Access for Everyone

Readers who archive the story for later reading -- perhaps because their Internet access is through a local library -- are able to see the physical characters used to construct the separators, and even primitive screen readers -- like the accessibility text to speech reader built in to your computer operating system -- will say something, even if it isn't clever enough to know what an ivy leaf looks like. The following element, for example, contains "hidden" characters interspersed with the visible decorations that will be pronounced if the screen is read aloud.

☙X❦X❧ (H4)

Here's how it's done:

<blockquote>

<h4 align="center"><big>☙<font color="#ffffff">X</font>❦<font color="#ffffff">X</font>❧</big></h4>

</blockquote>

It uses "Secret" (text with the colour set to white — accessed through the S button, seventh on the row above the edit box. You'll have to manually erase the text that says: {Highlight to read} ) Almost all screen readers will ignore the decorative hedera (ivy leaf) characters, but will pronounce the two X characters, which draws at least some attention to the break in the story flow.

It's not that much extra work, pays big dividends for disabled readers, and can be useful for almost everyone.

Puddin'

You shall not curse the deaf nor place a stumbling block before the blind — Leviticus 19:14

Note: To avoid having some of the code that creates the special characters automatically translated into the characters themselves, I poked a thin-space in between the ampersand and the number portion. This may cause the number to split across line boundaries, and will make it difficult to copy by highlighting it. If you see a space — or possibly a strange character like this: ¿ — between a copied & and a "number sign" or "octothorpe" ( # ) like this: & # with some numbers following after, then a semicolon, the way to fix it is to delete the extra space or strange character. For instance, &¿#160; should have the strange character removed.

How to count...

Author:

Taxonomy upgrade extras:

How to count...

by Puddin'

As a writer, you're meant to put words on blank paper. Accountants, on the other hand, are paid to put arabic numbers on paper with lines on it, which makes all the difference. Arabic numbers are not words, they're symbols, which don't actually translate all that well into real words. There are a whole set of rules that are absolutely mandatory when writers write using numbers, mostly to avoid confusion, but also to avoid looking like a rank amateur. The two instantly diagnostic symptoms of amateur writing are bad spelling, and the inappropriate use of arabic numerals.

The first thing a writer has to know about arabic numbers is that they're not precise, even though they look like they ought to be, and it's usually important for a writer to get the words right all the time. If you write: "Sam said, ‘It's 7:00,’" what the heck did Sam actually say? "Seven?" "Seven o'clock?" "Sevenish?" "Seven on the dot?" "Seven exactly?" "Seven AM?" "Seven PM?"" "Seven in the early evening?" "Seven in the morning?" "Oh seven hundred military time?" Those bare arabic symbols say nothing at all beyond what an accountant might dream of, and leaving important details as an exercise for the reader is rarely a good idea.

Every professional writing venue has what's called a "style guide" which details many of the rules associated with putting words on paper for that particular venue. Newspapers have style guides, as do magazines, as do book publishers, as do many web sites. This article addresses only the use of numbers, and offers explanations, which is rather more than most style guides do, since the typical response to submissions which don't follow the rules is to toss them into the trash.

Number Styles

Rule One — Spell out every isolated single-digit whole number. Arabic numerals should be used for large numbers, exact times, exact amounts, and certain other specific situations, but the exact point at which numbers become “large” varies. Some venues treat ten as a large number, but see rule two.

Correct Examples: The two of us went to town. I have 10,763 unique clips in my paperclip collection.

Rule Two — Be consistent. If you have a lot of small numbers that you spell out, and a very few larger numbers, you might consider spelling out every number. An exception may be made for extremmely large numbers, in which one may mix arabic numbers and spelled-out large portions of numbers, to spare your readers the difficulty of counting zeros. Likewise, if you have a lot of large numbers, which might use arabic numerals, you might consider using arabic numbers for everything, as long as you stick to one general topic, but see rule three.

Correct examples: One potato, two potato, three potato, four. I have forty-seven potatoes in all. The US military budget is $663.8 billion.

Incorrect example: The three of us carried 12 pounds each.

What consistency might be in any given instance may also depend on how you start out, but may be modified by other, less flexible rules.

Correct example: Whilst on my trip to the Moon, I collected 739 specimens of dust, 283 rocks, and 2 golf balls.

Incorrect Example: I’d ordered six eggs, but was given 66 eggs.

Rule Three — Never start a sentence with an arabic numeral.

Incorrect Example: 17 of us are astronomers.

Note that there are no "capital" arabic numbers, and it always looks stupid to start a sentence without a capital letter in English. If you have to use arabic numbers, for whatever reason, you either have to reword the sentence to put real words first or spell out the initial number, even if it’s ‘large.’

Correct example: Seventeen of us are astronomers.

Correct example: We're all astronomers, 17,639 of us.

Rule Four — Always spell out simple fractions and hyphenate them to make life easier for your readers. Unless consistency dictates otherwise, use ‘half,’ ‘a third,’ or other simple spelled-out fraction for common fractions.

Correct examples: We ate half the pies. Two-thirds of us were involved in the effort. A tenth of us were left behind. Three-quarters of the volunteers weren’t quite sober. An eighth of the men weren't qualified as yodelling cowboys.

Rule Five — Mixed fractions should be written as arabic figures unless, as dictated by Rule Three, it begins a sentence. Never use special glyphs for mixed fractions, like ¼, ½, or ¾, unless they are the only vulgar fractions used in a document, because this would violate Rule Two, which is all about consistency. Note that ¼ looks nothing like 1/5. Also, these special glyphs aren’t available in all fonts, nor are they guaranteed to exist at all, so your document may wind up with these characters looking either ‘odd,’ or invisible, on other people’s computers, if you use them at all.

Correct examples: The interest rate on secured deposits is 3 1/2 percent. Seven and one-half percent is the maximum you can expect on unsecured money-market accounts. Note that these two correct sentences would none-the-less violate the consistency required by Rule Two if they appeared in the same paragraph or talked about the same subject in a single document.

Incorrect example: Take 1 ¼ cup flour, then add 2 1/3 cup sugar, and mix slowly into 1 7/8 gallon of water.

Rule Six — Simple is better. If a number is ‘round,’ especially if it’s an explicit or implied approximation, spell it out. Arabic numbers tend to imply a precision which may not exist.

Correct examples: Into the valley of death rode the six hundred. Ali Baba and the forty thieves hid in the cave. There were hundreds of casualties. Almost fifty arrows hit the target.

Incorrect examples: We had 12s of eggs and didn’t know what to do with them. A few 100 bicyclists rode by the grandstand.

Rule Seven — Always use arabic numbers to express decimal numbers, and note that this implies precision. Put a single zero in front of a decimal number unless the decimal number begins with a zero.

Correct examples: Under the Rules of Golf, a golf ball weighs no more than 1.62 ounces (45.93 grams). The Euler-Mascheroni constant is approximately 0.577. There were only .07 parts per million of arsenic in the sample.

Incorrect example: Roughly 3.77 Girl Guides were assigned to sell cookies.

Rule Eight — In general, use arabic numbers for the days and years in dates, although they can be spelled out for stylistic reasons. Dates tend to look more formal when spelled out, and this is often done for formal invitations, as to a wedding. One can add ordinal indications if desired.

Correct examples: August 7th fell on a Saturday in 1909. January 9, 2007. December 21st, 1945. The 20th of November. June 2nd. You are cordially invited to Tea on October Fourth, Nineteen Hundred and Twelve.

Rule Nine — In running text, the time of day should always be spelled out, unless extreme precision is implied. If you use the idiom, ‘o’clock,’ the time must always be spelled out.

Correct examples: Dinner is served at eight o’clock. I plan to leave at three thirty in the afternoon. It’s seven oh seven in the evening right now.

Rule Ten — If you use AM or PM, use arabic numbers, and likewise when precision is implied, even when the precise time is on the hour, the half hour, or the quarter hour.

Correct examples: Dinner is served at 8:00am. The plane leaaves at 3:34pm. It’s 7:07 P.M. right this minute. The bomb is set to go off at 23:08.

Rule Eleven — Use noon and midnight rather than 12:00 P.M. and 12:00 A.M. Although they’re theoretically exact times, they’re also approximations of the location of the sun, like ‘dawn’ or ‘sunset.’ To be consistent, they have to be spelled out. Also, many people are confused about AM and PM in these contexts, and will often say ‘Twelve noon’ instead of 12:00 PM, or ‘Twelve midnight’ for 12:00 AM.

This actually makes a lot of sense. Other than amongst obsessive-compulsives, most people actually mean (or imply) ‘about’ when they speak of times. Few people will shoot you dead if you're one or two minutes late to an appointment made for ‘noon.’

Correct examples: She’s never up past midnight. We usually eat luncheon at noon. It’s high noon, on the dot. The take-off is on the stroke of midnight.

Rule Twelve — Hyphenate all compound numbers from twenty-one through ninety-nine unless using archaic forms for effect.

Correct examples: Ninety-nine bottles of beer on the wall, ninety-nine bottles of beer, take one down and pass it around, ninety-eight bottles of beer. Four and twenty blackbirds, baked in a pie. One hundred and forty-five ducks in a row.

Rule Thirteen — Never use arabic numerals in dialog.

Correct examples: “I plan to leave the office at half past five.” “Twelve-thirty is way past my usual bedtime.” “Happy New Year!”

Incorrect examples: “I plan to leave the office at 5:30pm.” “12:30 is way past my usual bedtime.” “Happy 01/01/2014!”

Hyphenetically Speaking

Author:

Blog About:

Taxonomy upgrade extras:

Hyphenetically Speaking

The Hyphen is one of those curious characters left over from ancient systems of writing, something like the ‘Pilcrow’ ( ¶ ) but much more common.

In Greek, it means ‘under one,’ (ὑπό ἕν = hypá³ hén) and was originally much like a simple underline written under two consecutive characters to indicate that they belonged to the same word. This helped to reduce ambiguity in phrases like:

‘WHENIWASACHILDANICEMANLIVEDNEXTDOOR’

By ‘joining’ the N and the I in this way, it was much simpler to distinguish the difference between ‘an iceman’ and ‘a nice man’. Everything else in this little sentence can be figured out with comparatively little effort, so of course they didn’t bother.

If you’ll glance at the blog entry on Paragraphs, you’ll see that spaces between words are a relatively recent invention, because parchment, which was made from real lamb skins, was way too expensive to waste on frivolous things like empty space when any fool could figure out where word boundaries were located for themselves.

Mind you, back in those days, speed-reading hadn’t been invented either, so taking half an hour to figure out what a single page of text meant was a worthwhile investment.

Well, to make a long story short, eventually cheap paper made of plant fibres was invented and the riffraff learned to read, thereby putting a lot of scribes out of business, since the act of writing a simple letter home was no longer a commercial transaction involving a third-party writer on one end and a third-party reader on the other. One still finds them in societies where illiteracy is common, but in most of the ‘Western World’ one needs them almost as rarely as one needs a blacksmith to shoe a horse or a tinker to mend a broken pot.

The appearance of spaces between words left the handy textual metacomment that the hyphen represented available for other purposes, and in fact it was drafted into service for several notions, the most common in handwritten missives being the underline which adds emphasis, usually represented in printed text as italics.

The second use — which also preserves the original meaning of a ‘joining’ between two things — is today’s ordinary hyphen, which we use for many purposes hovering around some sort of linkage, whether explicit or implied.

- Hyphenated Names

- In some traditions, and in some families, it’s customary to join the family names of certain married individuals with that of their spouses, that is: Mary Smith, MD might marry Joe Schmoe, carpenter, and decide either to keep her professional name, Mary Smith, MD, or to hyphenate it with her husband’s name, Mary Smith-Schmoe, MD. Joe might or might not make the same choice, and this is usually a matter of negotiation these days, at least in civilised society. These sort of hyphens are never optional, but required, despite the fact that many applications fail to accept hyphens (and many other characters) as legal characters in names.

Roughly the same situation exists for the nobility, except that the usual scheme was for a woman who married a man of lesser social status to retain her higher-status family name as part of a blended name, with the husband adopting the blended name as well. Which name comes first is often a matter of personal preference.

Likewise, some given names are hyphenated, like Jean-Claude Van Damme or Jean-Paul Sartre, so if you’re ever in charge of designing an input field for names, don’t be a boor. Many people use ‘unexpected’ characters in their names, like José Feliciano or Já¼rgen Todenhá¶fer. It’s polite to let people do pretty much what they want to do with their own damned names, to say the least. ASCII character input fields may have made sense in ancient times, let’s say 1991, but ever since Unicode became an international standard, there’s little or no excuse to pretend that every modern computer doesn’t support every character used in every major language in the world.

- Distinguishing Homophones

- Just as in the original use of the hyphen, one major purpose of their use is to eliminate ambiguity concerning similar-sounding words, so resource, a supply of money, raw materials, or other assets can be easily distinguished from re-source, to find or acquire another supplier for a particular item or asset.

- Conventions

- Many words are strung together so often that they’ve acquired a meaning of their own, at very least slightly separate from the meaning of the individual words combined. As an example, hard-boiled can refer either to an egg or to a detective in a certain type of novel, although this is a very similar use to the tradition of distinguishing between substantive and attributive uses of the very same string of words.

- Distinguishing attribution from substantiation

- A woman who is thirty-four years old (an attributive use) can be described as a thirty-four-year-old (a substantive use). In general, when you make a string of adjectives into a noun, you’re often well-advised to glue the pieces together with hyphens.

- Ambiguity

- The manner in which we jam words together is often ambiguous, if you can’t actually hear the person creating the words, so we often tie certain words together with hyphens if they’d normally be strung together in speech. High-achieving students are a rather different matter to high achieving students.

The wine-dark seas of Homer (attributive) might either be described as wine dark (predicative) or as wine-dark, depending on how the speaker believes the words ought to be spoken and the exact usage of the words involved. Some words are inherently ambiguous without the context supplied by one or more associated words, so a safe cracker isn’t quite the same as a safe-cracker. The first might simply be gluten-free, whilst the second is more probably a felon.

- Standards

- Over time, some types of hyphenation are falling into disuse, especially in the UK and places influenced by UK usage. Most professional writing follows a style guide, and writers who make money at it typically pay close attention to whatever standards they’re expected to adhere to. Even in the self-publishing field, one of the more common criticisms made by reviewers is bad grammar, spelling, and general sloppiness, many of which have resulted in returns for credit. That’s the dark side of publishing for the Kindle or Nook or iPad, because that ‘sale’ that flows so easily from a few ‘clicks’ on the part of the reader can be just as easily reversed, as long as the retailer’s time limits haven’t been exceeded.

- Style Guides

- The most accessible is probably the Wikipedia version, which can be found here: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia%3AManual_of_Style It has the great advantage of being free for anyone to use.

The Associated Press Stylebook is very valuable for newspaper reporters and print publishers, because it pays attention to the requirements of print media, and so values space-saving conventions. The online version is available here by subscription: http://www.apstylebook.com/ or you can purchase the print version through any bookstore.

The Tameri Guide for Writers is available online here: http://www.tameri.com/edit/style.html It tracks the AP Stylebook fairly closely, but has the advantage of being available gratis.

The Modern Language Association Handbook is very popular for scholarly writers in the humanities, especially academic writers. It’s available online here: http://www.mlahandbook.org/ and one ‘purchases’ online access through purchasing a copy of the current printed book, all of which contain access codes.

The Guardian Styleguide is available online here: http://www.theguardian.com/styleguide There’s no charge for online use, although they also sell an updated printed version. It’s nice for UK usage.

The BBC News stylebook from a while back is available as a PDF here: http://www2.media.uoa.gr/lectures/linguistic_archives/academic_papers0506/notes/stylesheets_3.pdf They do have a more recent version available to people in the UK available here: http://www.bbc.co.uk/academy/journalism/news-style-guide but you’ll be intercepted unless you’re ‘local,’ the theory being that UK citizens have paid their license fees and are thus deserving of BBC largesse. On the other hand, About.com has a freely-available version here: URL Gobbledygook from About.com

In Canada, you might want to take an online look at The Canadian Style: http://www.btb.termiumplus.gc.ca/tpv2guides/guides/tcdnstyl/index-eng.html?lang=eng

You might also want to take a look at the famous The Elements of Style by Strunk and White, which is described here: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Elements_of_Style

Strunk and White has its detractors, but few writers would ignore the overall thrust of the work. It’s well worth having, even if you use it as a source of arcane ‘rules’ that you’d personally prefer to flout.

I Should Be Writing

Author:

Blog About:

Taxonomy upgrade extras:

Here's a lovely little ditty for the writers among us:

I Should Be Writing was commissioned by Mur Lafferty as the theme song for her podcast.

Inserting the copyright symbol

Author:

Taxonomy upgrade extras:

The Copyright Symbol ©

Inserting the copyright symbol

by Puddin'

While it's possible to simulate a proper copyright symbol like this: (c)

It looks a little more elegant to use the authentic character: ©

It's not hard. All you have to do is type what's called an entity in the HTML/Web world, either a named (or mnemonic) entity using alphabetic characters or a numeric entity using assigned numbers, either option surrounded by "escape" characters that let your Web browser know that it should do something "special" with the mnemonic characters or assigned numbers. The escape characters are the ampersand (&) and the semicolon (;)

The numeric entity that will be turned into the copyright symbol is:

©

The mnemonic entity that will be turned into the copyright symbol is:

©

If you want to display an actual code in the screen text, as I do here to show you how to do it, you will have to "escape" the leading ampersand like this:

&copy;

although Big Closet sometimes ignores the "escaped" escape ampersand character, especially with numeric codes. Test it before you commit your edit. Luckily, there are few reasons to do this, other than to be absolutely certain that an intended ampersand will be properly displayed, so Big Closet's odd behaviour isn't usually a problem.

There are a raft of others which can be found here:

if you want to "spice up" your text with authentic accented characters (É), most common Greek letters (Ψ), and whatnot (¶).

It's important to use the actual escape character, and not some clever symbol inserted by your word processor, because different computers use different symbol sets, and if you use a character that's not in the user's character set, it will look something like this: ’ or this Â, when you meant something else entirely.

The default character set for the Internet is essentially the characters you can see on your keyboard. If the character you want isn't there, you have to "escape it" with an "entity" as shown above.

While not a "character," a lot of authors have good and sufficient reason to want to use indented text. Whilst there are a number of kludges floating about using non-breaking spaces and the like, the most reliable way to generate indented text is with HTML <blockquote> tags, which should be used in pairs like this:

<blockquote>

Stuff to be indented.

</blockquote>

Pay particular attention to the stroke (or forward slash) in the last "blockquote" tag since, if you don't close the tag pair properly, your text will start wandering to the right.

All of the above indented text was generated in just this manner.

An easy way to generate a pair of these tags online is to use the Q button at the top of the Big Closet editing screen.

You can then cut and paste them anywhere, or insert them at the point where you want the text indented and than cut and copy the closing tag and move it to where you want the indentation to stop.

Have fun!

Let’s Rest a Spell

Author:

Blog About:

Rarely Confused Words, Sort Of…

| Usually Intended | Often Mistaken | |

| Disdain – To hold in contempt | Distain – To stain or tarnish | |

| Distain is so rarely appropriate these days that it’s almost certainly a mistake, unless you’re still living in the Eighteenth Century, but most so-called ‘spelling checkers’ allow it. | ||

| Whose – The possessive of ‘Who’ | Who’s – A contraction for ‘Who is’ | |

| There are exactly zero possessives of the common pronouns formed with apostrophe ‘S’ in English, but most so-called ‘spelling checkers’ either allow or encourage the confusion. | ||

| Compliment | Complement | |

| When one says something nice about another person one ‘compliments’ them. | ||

| When things go well together they complement (or complete) each other. | ||

| We have a full complement of baseball players. | ||

| Our latest acquisition, the Biltmore in New York, complements our chain of hotel properties. | ||

| The easiest way to distinguish the two is usually one of agency. | ||

Feel free to add your own pet peeves…

One of These Days, Let's Get Organised!

Author:

Taxonomy upgrade extras:

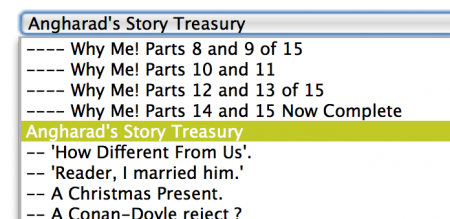

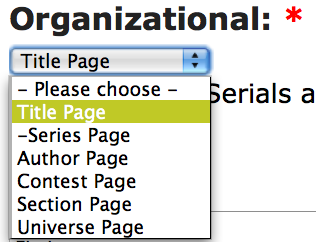

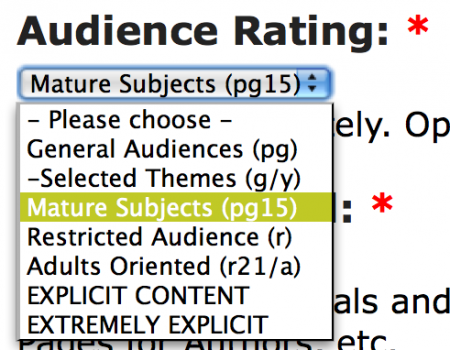

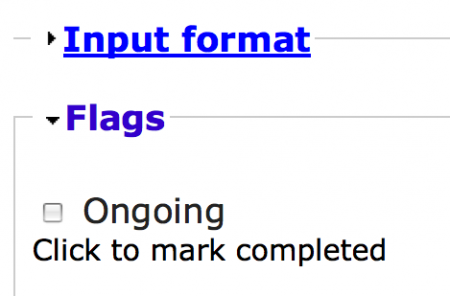

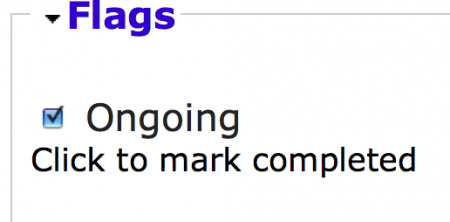

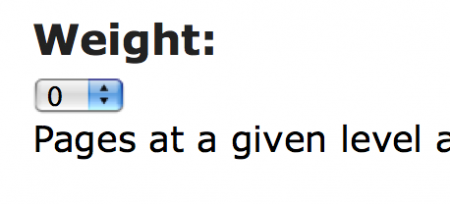

At the top of the screen, usually over toward the right if you use the default ‘appearance’ for BC, you’ll see a row of links (you can click on them) preceded by ‘++’ that looks like this:

Click on ‘++Organizer’.

An edit screen will appear with various blanks to fill in. Everything that simply must be filled in is marked with a colourful asterisk.

Most of the fields are self-explanatory, but be aware that the field at the very top labelled ‘Title’ can be repurposed for other uses. For a multi-part story, you’d enter your overall story title, lets call it ‘My Story’. If you’re creating an Author page, your Author name will go here instead.