Melissa Tawn

Author:

Organizational:

Audience Rating:

Taxonomy upgrade extras:

Melissa Tawn

A Heroine of our Time

Author:

Audience Rating:

Publication:

Genre:

Character Age:

Permission:

A Heroine of our Time

|

|

CHAPTER 1. THE DAUGHTER OF AN EARL

Lady Penelope Effingham was the daughter of the sixth Earl of Markham. Slim and athletic, she was an avid tennis player who could hold her own against men as well as other women; she was considered a beauty and was courted by many very desirable young men, though she had not shown a clear preference for any one of them. She was also a brilliant conversationalist and writer who, at the age of 20, had already published two slim volumes of poetry which received measured praise from the critics of the day. Penelope’s father travelled often and maintained a chateau in the Loire valley in France and a small mansion in the suburbs of Berlin, at both of which Lady Penelope spent considerable portions of her childhood. As a result, she was totally fluent in both French and German, as well as in Latin, which she had taught herself.

And then the second great European war came and, after working in various volunteer jobs, Lady Penelope suddenly disappeared from public view. Her friends and even her siblings had no idea where she was at, and they knew enough not to inquire. Her father did know, but did not talk about it. Only after the war did it become known that she had been approached by Colonel Colin Gubbins, an old friend of her father, who asked her to join a very clandestine organization which was being set up, the Special Operations Executive (SOE). The SOE was founded in June of 1940 and dedicated to conducting covert operations behind enemy lines. Lady Penelope joined without hesitation. After a year of conducting language classes for SOE operatives at the SOE’s first headquarters at 64 Baker Street in London (which led to the nickname “The Baker Street Irregulars”) and then at Wanborough Manor in Guildford, she volunteered for frontline action. She was trained as a wireless operator and was dropped into France in the fall of 1941 to act as liaison with the French CLOUCHE resistance network.

For seven months, the CLOUCHE network conducted sabotage raids against German targets, helped rescue downed British airmen and convey them to Spain or Switzerland, and provided highly valuable intelligence data on German operations in the Paris area. Then, somehow, the Gestapo and the Sicherheitsdienst (SD) were able to identify and penetrate them and, in a coordinated operation, all of the network’s leaders were rounded up or killed. Lady Penelope was apparently surprised in her bed in the garret where she slept. When her friends came the next morning, they found signs of a struggle and a blood-stained bullet-holed bed sheet. The Gestapo had apparently taken Penelope - dead or alive - with them. Her body was never recovered nor did any Gestapo records as to what happened to her ever come to light.

After the war, when the story of the SOE was published, the tale of Penelope Effingham was one of the highlights - the intelligent, beautiful, aristocratic young lady who sacrificed herself for the cause of fighting the Nazis. Those who knew her during the war told and retold stories of her courage, her leadership, and her sweetness which kept them going in many a dark hour. At least three books and two movies appeared based (rather loosely) on her life. The bullet-holed bed sheet stained with her blood was prominently displayed in the Imperial War Museum in London. Then, as inevitably happens, the interest in Penelope Effingham waned. A new postwar generation grew up that cared more about the future than the past, and the generation after that knew or cared even less about the war. Even the endless sequence of BBC and History Channel documentaries about the war seemed rather lifeless after a while. The story of Penelope Effingham, SOE heroine, became a footnote in a tome now rarely removed from the shelves.

CHAPTER 2. THE REVIVAL OF INTEREST

The revival of interest in Penelope Effingham came, surprisingly, not from her wartime heroics but from the two volumes of poetry she had published before her 20th birthday. Academic researchers in the late 90’s stumbled upon them and decided that they had a seminal influence on modern British poetry. Hugh Malcolm, a Cambridge don and expert on contemporary poetry, led the way with a brilliantly-written treatise entitled “The Eff Factor” in which he maintained that the poems Lady Penelope Effingham had a direct and major impact on all poets after the war, whether they were aware of it or not. Indeed, he diagrammed these effects with a series of eye-catching diagrams showing lines of influence (which he called “Eff-rays”) emanating from her to everybody else. Malcolm’s book, originally intended for specialists, became a best seller and the quickly-reissued volumes of Penelope’s poetry sold out as fast as they could be reprinted. Her image changed - instead of being seen as the heroic secret agent and fighter, she began being portrayed as the great and promising poet who was martyred in a useless and needless display of senseless patriotism. (In the big picture, one must admit, the heroics of the SOE were essentially negligible and contributed very little to hastening the end of the war or influencing its direction.)

The BBC was quick to announce that it was funding a new miniseries about her, and that it had commissioned a special group of historians and forensic scientists to try and find the answer to the mystery of what happened to Penelope after her capture and to locate where she was buried. If her bones were found, they would of course be brought back to Britain and reinterred in the Poets’ Corner of Westminster Abby, alongside of Geoffrey Chaucer, Lord Byron, Robert Browning, Alfred Tennyson, and many others.

CHAPTER 3. WHO WAS PENELOPE EFFINGHAM, REALLY?

While the BBC’s group of historians (and their graduate-student and research-assistant camp followers) headed for France and Germany to look for clues in the Gestapo archives which had survived the war, the forensic scientists concentrated on the only physical clue they had - the bullet-holed and blood-stained bed sheet still on display at the Imperial War Museum. Using the techniques of modern science, they were able to extract some DNA samples which, while barely usable, still might provide some information. These they intended to compare with DNA taken from Penelope’s only surviving sibling, her brother Herbert, now in his 80’s but still in full command of his mental facilities. Herbert Effingham had spent the war on the staff of Lord Mountbatten in Kandy and, after the conflict was over, parlayed the contacts he made into a very lucrative import/export business from which he had retired only at the age of 75. (The Earldom had passed from his father to his older brother Oliver and then on to Oliver’s eldest son, so Herbert Effingham was free to concentrate on making money without worrying about the burdens of aristocracy.)

When Dr. Hollis McBride, the head of the BBC’s forensic team, contacted him, he was of course willing to provide a DNA sample. Unfortunately, he had no papers or other memorabilia of his sister, all of these having been destroyed when the south wing of Markham Manor suffered a direct hit by a V-2 missile in the closing days of the war.

Dr. McBride duly arrived for their appointment two days later, and startled Herbert by telling him that he had made an amazing discovery, and so would not need a DNA sample after all. “What is that?” asked Herbert. “The blood on the sheet is not your sister’s blood,” replied Dr. McBride, “I know that for certain.” Herbert wondered how Dr. McBride could be so sure, without having another DNA sample to compare it to. “We did a preliminary analysis,” explained Dr. McBride, “and found that the blood is definitely of a man. Therefore it cannot be your sister’s.” Dr. McBride went on to explain that the historians were all very excited about this find, since it opened the question that if Penelope Effingham was not killed in that garret, what happened to her? Was she overpowered and taken alive to a Gestapo prison? Or, perhaps, did she go willingly? Maybe she was the traitor who told the Gestapo about the CLOUCHE network to begin with? She had, after all, spent a considerable amount of her girlhood in Germany - perhaps her loyalties secretly lay there?

Herbert Effingham sat quietly and looked very sad while Dr. McBride kept spinning wilder and wilder theories. Finally, he interjected quietly. “My sister was no traitor, and she did die in that garret.”

“I am going to tell you a long-hidden story,” he continued, “and then I am going to ask you and your group not to use it in any way. The story begins when I was four years old - barely old enough to understand what was happening around me. At the time, I had two brothers: Peter, the eldest, and Oliver, who was two years older than me. My mother had passed away a year before, and we were being raised by various governesses. As you pointed out, we lived in Germany quite a bit in those days, purportedly for my father’s business interests. Only many years later, after my father also passed away, did I find out that he really worked for SIS and was there collecting information on German industrial production and its military implications. One day, my father called us all into his study and told us that Peter was in the hospital, and it would be a while until he returned. But that when he returned, he would no longer be Peter any more, but would be a girl, whom we were to call Penelope from now on. We were not to pester her with questions, but just accept that this is what had to happen. Some of the governesses giggled and some were shocked (and one even tendered her resignation the next day) but Oliver and I, being little children, just accepted it as part of the game of life, which we were still learning how to play.

It was only several years later that I had the courage to ask Penelope to explain what had happened. She was very frank, as was her way. She told me that she had always felt she was a girl, even though she had the body of a boy, and discussed the matter openly with our parents. She sufficiently convinced them of her seriousness - but then she was always a very convincing talker - that my father took her to see a Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld who, in 1931, performed the first “sex-change” operation on Lili Elbe and on another person, whose name is known only as “Dora R”. Surprisingly, Dr. Hirschfeld was very slow and careful in arriving at his diagnosis, and called in not one but two psychologists to subject Penelope to a long series of interviews and tests. Only after almost a year, he concluded that she would be a good subject for another such operation.

Dr. Hirschfeld’s first two operations had been only qualified successes, mainly because the subjects were already adults who had been homosexually active and had definite sex drives they wished to fulfill immediately. These expectations were never met. He hoped, however, that by operating on someone who had not yet reached puberty, he would cause the body to secrete female hormones of its own accord and thus Penelope would be a more “normal” female. My father agreed to the operation which, for obvious reasons, was done under conditions of complete secrecy at a private clinic in Berlin. Dr. Hirschfeld had planned to follow Penelope’s subsequent development closely, but in 1933 the Nazis sacked and burned his offices and library in Berlin. He was out of Germany at the time, and never returned. Instead, he settled in France, first in Paris and later in Nice. Penelope was able to see him on a few occasions, but since her files had been left behind in Berlin, there was not much he could do. In 1935, Dr. Hirschfeld died of a heart attack.

While there is no clinical data, it does appear that Dr. Hirschfeld’s theory that Penelope’s body would generate its own female hormones was justified, for - as you know - she became a very lovely and very feminine lady.”

At this point Herbert Effingham took a longish break, and looked silently at the wall of his study. Then he continued.

“Of course, I knew nothing of what Penelope did during the war though my father who, as I told you, was in the SIS, most certainly did. After the war was over, he was determined to find Penelope’s body and bring it for burial in England. He had many chits that he could, and did, call in and was finally able to piece together the story of what happened to the CLOUCHE network with the help of some former Gestapo officers who, subsequently and rather unexpectedly, were granted early rehabilitation by the West German government. Basically, the story is this: while it is true that Nazi hotheads burned down Dr. Hirschfeld’s institute and library in 1933, many of his medical files were “rescued” by far-sighted leaders of what later became the Gestapo, who could foresee their possible future use. Among these was Penelope’s file. When, a few months after her arrival in France, she was identified on the street by a Gestapo informant, somebody managed to put two and two together and realize that they could blackmail her into working for them.

The Gestapo sent four men to confront Penelope. Of those four only one, Hans Joachim Mecke, survived the war. In 1949, he was personally interrogated by my father in a safe house not far from Bonn. According to Mecke, the four broke into Penelope’s garret and confronted her with her medical file from Dr. Hirschfeld’s clinic. They offered her a choice - act as their double agent inside the CLOUCHE network or the file would be leaked to the British authorities and to the “neutral” press in Sweden. While pretending to reluctantly acquiesce with their offer, Penelope reached for a gun she had hidden underneath her pillow and shot the leader directly in the head. Mecke pulled his gun and killed her on the spot. The three Gestapo agents then took both bodies away with them. Hans Joachim Mecke gave the exact details of where her corpse was dumped. He then had no more information to provide. As sometimes happens in such situations, he did not survive the interrogation. Pity.

My father managed to locate Penelope’s body where Herr Mecke said it would be and, using dental records, confirmed that it was indeed hers. He then secretly brought the body back to England. She was cremated and her ashes were scattered in the copse of trees where she often sat while writing her poetry, here at Markham Manor.”

Again, Herbert Effingham paused for a few moments.

“I have absolutely no documentary or other evidence to back up what I have just told you, nor will you be able to find any corroboration to it. If the BBC tries to air this story it will be skating on some very thin legal ice indeed. The SIS does not like tales like this to float around. I strongly suggest that the whole miniseries project be dropped.”

And so it was.

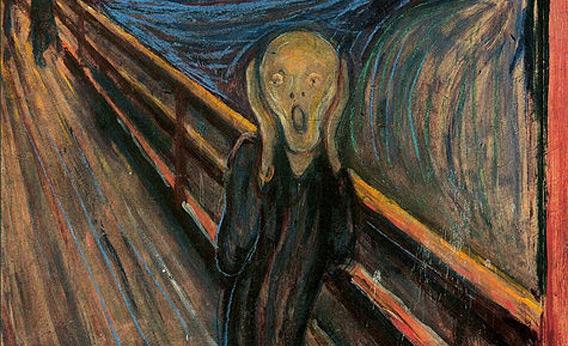

EPILOGUE: This story is fiction but, as usual, I have incorporated real people in walk-on roles. One of these is Colonel Colin Gubbins, Director of Operations and Training at the SOE, and the other, of course, is Dr. Marcus Hirschfeld, the flamboyant Berlin sexologist who performed the first sex-change operations. The character of Penelope Effingham is loosely based on that of Noor Inayat Khan, the Indian princess (raised in England and France) who served as an SOE wireless operator with the PHYSICIAN network in France; she was arrested by the Germans in 1943 and later executed by them. It is her picture which appears at the top of this story.

Adam's Pregnancy

Author:

Audience Rating:

Publication:

Genre:

Character Age:

TG Themes:

TG Elements:

Other Keywords:

Permission:

|

----------=BigCloset Retro Classic!=----------

Adam's Pregnancy

How Adam became pregnant, learned to live with it, and liked it!

|

|

Admin Note: Originally published on BigCloset TopShelf on Thursday 11-09-2006 at 12:15 am, this retro classic was pulled out of the closet, and re-presented for our newer readers. ~Sephrena

Adam Domanski considered himself to be lucky to have all of the opportunities he had in life. His father, the late Prof. Wlodzimierz Domanski, defected from Poland at the height of the Cold War by single-handedly stealing a light plane and piloting it to Denmark, flying very low to escape detection by the Polish and East German radar. After a short period of newspaper and television fame, he settled down to the relative obscurity of teaching chemistry at a small American college, met and married a Polish-American woman from Chicago, and fathered one child, Adam, who was brought up in a household which was both deeply conservative politically and very Catholic. The language of the house was Polish, and Adam grew up speaking it fluently.

Adam was a good and serious student, who met and, in turn, married a good Catholic girl, Mary-Ellen McCarthy, while both were undergraduates. They were virgins until their honeymoon. After he graduated with honors, Adam went on to law school, where he had achieved good grades, but -- to admit it -- did not find much satisfaction in the minutae of the law. One day, one of his law professors called him into his office and asked Adam for help. The professor had been doing some consulting to an American corporation which was trying to sign a very large export deal with the Polish government, and urgently needed some legal documents translated from Polish to English. Did Adam know anyone who could do it? Adam offered to do it himself, and found that he had no trouble at all finding the precise translations of the legal terms. He even liked the task, and was very surprised when the professor insisted on paying him at the going rate -- over $5000 -- for his work.

The word got around and soon Adam decided that he had found his vocation. He left law school at the end of the year and opened an office for legal translations. First, it specialized in translations between Polish and English, which he did himself. Later, he added a young Russian-American lawyer, Olga Yablokova, who handled legal translations between Russian and English and an African-American woman, Tracy Green, who had a master's degree in Slavic languages from Georgetown University and several years' experience in a government agency (best left unnamed -- as she put it, since No Such Agency exists) before she decided to leave Washington after her husband died on assignment for the same unnamed agency. Since Tracy had no law background, she acted as office manager in order to free Adam and Olga to concentrate on actual translation work. Clients would talk to her first, and would usually be startled when she conversed with them in fluent Russian, Polish, or other Slavic languages. Since she was also a generation older than Adam and Olga, she soon became the office "housemother," helping everyone with their personal problems as well. When Adam's father died suddenly of a stroke, she comforted him and helped him get over the loss and the pain. Finally, Maria Wajch, a young lady just out of high school, joined the group as secretary and general gofer.

Adam and Mary-Ellen were very much in love, and that love grew over the years, though it was accompanied by one deep sorrow: they did not have any children. Many years and dollars were spent on various doctors and spiritual counselors, but to no avail. Finally, after many tries, Prof. Harrison at the University Hospital pinpointed the problem -- a malformation in Mary-Ellen's womb which prevented any fertilized ovum from developing. There was hope, however, albeit rather slim: the doctor suggested an experimental technique whereby an ovum from Mary-Ellen be fertilized by Adam's sperm in a laboratory, and them implanted outside the womb, where -- if the implantation was done early enough in its development -- it could develop in its own placenta. The baby would then be delivered by Caesarian section, when the time came. This procedure, he explained, had been successfully tried on sheep and cows. but had never been done on humans. His team, however, had obtained permission from the hospital Ethics Committee to attempt it and, if Adam and Mary-Ellen were willing, the cost of the procedure and followup treatment would be covered from their research grant.

After a lot of soul searching and prayer, and after consulting with their parish priest, they agreed. Three months went by, as Mary-Ellen was extensively tested. Then, the day finally arrived. In separate rooms, Adam contributed sperm and Mary-Ellen contributed ova. They were told to wait for two hours to see if the laboratory fertilization was a success. Having nothing to do, they decided to go to a coffee shop across the road from the hospital, to get something to eat. They were so excited, they held hands and had eyes only for each other. As they crossed, they did not see the car, driven by a highly intoxicated driver, which ran a red light and was headed directly towards them ...

When Adam woke up, he was in a hospital bed, with one leg in a cast and traction and his head and left arm heavily bandaged. He felt terrible. Next to him sat his mother, and Father McQueen, his parish priest. Crying, his mother filled him in on what happened: Mary-Ellen had been killed outright in the crash, and Adam had been unconscious for over 24 hours. There appear to be no major injuries, but he would have to remain in the hospital for at least another three weeks. (He was lucky that the accident occurred right outside of the hospital, so that he was rushed into ER immediately, which was probably what saved his life.) He could not even get up to attend Mary-Ellen's funeral. Needless to say, Adam was crushed, and even Father McQueen's kind manner did little to comfort him.

It took almost a week before Adam's grip on reality returned, and he was able to think straight about his situation and about the future. His mother and Father McQueen had been daily visitors, as had been Olga, Tracy and Maria, who assured him that the work at the office was continuing with no problems and that he should feel free to take as much "leave" as necessary from the pressures of work. The couple's many friends filled the room with flowers and kind words about Mary-Ellen and there was talk of suitably memorializing her contributions to various church activities.

And then, a week after the accident, Prof. Harrison and his assistant, Dr. Anne Mayberry, came to visit, bringing a problem that had to be solved immediately. Everyone, it seems, had forgotten about the original purpose of Adam and Mary-Ellen's visit to the hospital -- the fertility treatment. The lab tests had shown that Mary-Ellen's ovum had, indeed, been successfully fertilized, and the embryo was now developing. It was time, imperatively, to make a decision what to do, since the embryo could not be kept alive in the laboratory for more than a few additional hours. Adam's eyes immediately filled with tears -- it must be allowed to live, so that it will be, in some sense, the continuation of Mary-Ellen's life. Was there not any other woman in whom it could be implanted?

Dr. Harrison explained that there would be no chance of implanting the embryo in a stranger -- the body would reject it. The only hope was finding somebody which a close genetic identity to the parents. Unfortunately, Adam was an only child, and Mary-Ellen had two brothers, but no sister. Adam asked for a few moments to consult with Father McQueen. It was the priest's opinion that, from the Church's position, everything should be done to save this living thing struggling to be born. There seemed to be no way out, and he and Adam both turned to silent prayer and asked for guidance.

Finally, Adam came to a decision. Calling Dr. Harrison back into the room, he asked, "Can you implant the embryo in my body?" Dr. Harrison was startled, but admitted that it might be possible. "Then do it," said Adam, "Mary-Ellen gave her life so that child might be born; I cannot have its death on my conscience." Things moved quickly. Within two hours, Adam had been sedated and transferred to a gurney. When he was returned to the room several hours later, he was still unconscious, but there was an additional scar on his abdomen, where the embryo had been implanted. Now it was a matter of waiting to see what would happen.

For another three weeks, Adam remained in the hospital, immobile in his bed while his leg and arm healed. Twice daily, members of Prof. Harrison's team visited him, took blood and urine samples, and sometimes scanned him with various exotic machines. Finally, when he was ready to leave, he was taken in a wheelchair to the office of Dr. Mayberry, who would be directly in charge of monitoring his progress.

"Call me Anne," she said, "We are going to be seeing a lot of each other for the next nine months. How do you feel at the moment?" she asked with a smile.

Adam said that he didn't feel anything special, and was sure that the implant had failed.

"No," said Anne, "it worked. You are, as best we can determine, pregnant. The embryo has built a placenta around itself, and is developing as one would expect. Your body is undergoing many changes, without you feeling them. Our tests show that it is producing a large quantity of female hormones, estrogen and progesterone -- this is necessary in order that the baby develop properly. We will give you additional shots to aid the process. You will notice the changes in a few weeks, when your breasts begin to grow. The areolas around your nipples will enlarge and darken too. This is necessary as your body begins to prepare itself towards breastfeeding after the baby arrives. In general, expect that your body will also become more feminine. Your voice will change, and so will your psychological reactions. You are also going to feel more tired. That too is normal. Also, be prepared for the possibility of nausea in the morning or at other times during the day. The important thing is to eat properly, get plenty of rest, and be mentally prepared for what is coming. I will be seeing you as often as you need me to, but certainly twice a week, because we want to keep a very close record of your physical changes."

Adam just sat there, not knowing what to say. He looked at the floor, not at the doctor. Anne smiled. "I know you suffered a great loss, Adam, that nothing can repair. But you also have elected to have the unique chance of bringing a life into the world, and be part of that wonderful miracle which God has given to the human race. So be proud of yourself, hon, and carry your baby with love and dignity." She gave him a booklet for pregnant mothers, and a swift hug, which he did not return.

Adam's mother drove him back to his house. He sat in the car and looked moodily at the floor of the car and did not speak. When they arrived, he got out of the car, felt dizzy all of a sudden, and then vomited all over the garage floor. His mother was horribly frightened, and wanted to take him back to the hospital, but he said no, and told her that he had something to tell her when they went inside. It was going to be somewhat of a shock.

"I am going to be a grandmother," she said after Adam explained what happened. "This is not the way I anticipated it, but you made the right decision, and I will stick by you and help you any way I can."

Adam hugged her tightly. "I need it mom, I need all of the love and care I can get very badly. For now, I just want to rest. I feel very tired."

Adam's mother understood, and unpacked his bag, while Adam slipped into bed. She smiled when she saw the booklet which Dr. Mayberry had given him, and thought about her own pregnancy. She must have dozens of things in the attic which Adam will need. She would have to check things out. She remembered how important it was that her mother was there with her; it was tenfold more important that she be with Adam, and offer her total support.

Tracy, Olga and Maria came over that afternoon, and Adam felt that he had to tell them about his situation too. They were overjoyed, especially Olga and Maria, who wanted to know everything he was feeling. He had to promise to tell them what it was like at every stage of the pregnancy. Tracy was much more practical. Her first concern was who would take care of him now. "You clearly can't do all of the housework yourself, in your condition," she insisted, "especially since you don't have a man to help you out."

Adam was afraid that it wouldn't "look right", but the next day, after vomiting again while trying to make morning coffee, he gave in. A compromise was reached: he talked to Dr. Mayberry and they decided that a nursing student would be assigned to live in Adam's house and take care of him, while at the same time monitoring his medical progress. That afternoon she showed up, a diminutive and almost-hyperactive young lady named Kathy Stryon, who said that she had experience before with "expecting mommies" and could handle anything. When Adam laughed at that description, she just smiled and said that Anne insisted that she treat Adam just like any other pregnant woman. "In fact," she decided, "from now on I am going to call you ... Wanda, which will be more appropriate as things get ... rounded out." Adam was not too crazy about that but Tracy, when she came over that afternoon with a large supply of groceries, loved it. "It is a good Polish name, hon," she said. "Just think about Wanda Landowska, the famous Polish concert pianist. You are going to be Wanda, the loveliest mother in the office."

After a few days at home, Adam (or Wanda, as everyone -- including his mother -- now insisted on calling him) felt ready to return to the office. (Working at home was not an option; he needed to have ready access to the large library of books on Polish law which was kept in the office.) He had gotten used to the morning sickness and managed to live with it. His chest area was very sore, and he did notice some swelling there, or so it seemed. He also noticed that he didn't need to shave any more. Kathy insured that he stick to a healthy diet and did some mild exercises to help overcome his tiredness. Still, he found out that it was harder for him to concentrate on work, and that every so often he would just sink back in his chair and stare at the wall. When that happened, Olga or Maria would come in and give him a hug and a kiss on the cheek, and ask him if he was all right.

There were days when he could work well, but days when he would feel so dizzy and lightheaded that nothing would get done. Maria had gotten into the habit of putting a vase of fresh flowers on his desk in the morning, saying that expectant mothers should have happy things to think about. He no longer objected to being referred to as a woman. Indeed, it was beginning to feel sort of natural. And when one of the "other" girls in the office kissed him, he would blush and smile. And he would think about the baby. He would often dream about it, living inside him, turning from an embryo into a fetus, and from a fetus into ...

At the end of the second month, Dr. Mayberry was able to tell Wanda that they now knew for certain that the fetus was female. Wanda kissed her. He had been hoping so much for a girl, who would of course be named Mary-Ellen.

As the second trimester began, Wanda began noticing that his clothes no longer fit well, they constricted him. His mother, Tracy, Olga, Maria, and Kathy were all of the same opinion -- he had to buy maternity wear, including maternity dresses. However, Wanda objected that he couldn't very well go around looking like a "man in a dress," and so they decided that he had to be taught how to present himself as a woman. That meant, of course, getting an appropriate hairstyle, learning the appropriate mannerisms, and learning how to dress in a whole new wardrobe. Wanda did not like the idea, but he was clearly outnumbered and, really, was too lightheaded and uncertain of himself to argue much. In fact, he noticed that for the past month or so he was unable to really make a decision and stick to it. He did what he was told. Tracy had taken over the total management of the office and she assigned work to him just as she did to Olga, That was OK, however; he was not sure he could trust himself to make business decisions any more.

And so, one day Tracy and Wanda's mother came over while he was away at the office, bagged all of his male clothes, and put them in the attic. In their place, they brought a complete selection of maternity slacks, skirts, tops, and dresses, comfortable but stylish shoes, and lingerie, including the bras which he was beginning to definitely need. Frilly nighties replaced his pyjama, and a dressing table was added to his bedroom, with enough lotions and cosmetics "to cover the world," as he said later. A well-stocked jewelry box was added, containing some very expensive pieces handed down from his grandmother. Of those, the most important, in his mother's words, were his grandmother's wedding and engagement rings. Wanda should wear them all the time, she insisted, so that nobody would whisper behind his back. Surprisingly, they actually fit his ring finger. Kathy took it upon herself to redecorate Wanda's room in an appropriately-feminine style. At the same time, Wanda's mother brought over many things that she felt that would be needed, including a sewing machine, which she insisted on teaching Wanda how to use, and some baby furniture for the guest bedroom, which was to become the baby's room in time.

It was not easy. Despite all of the support from his own "fabulous five fans," as Wanda liked to call them, Wanda had a hard time adjusting. The first time he came to the University Hospital dressed in a skirt and blouse, even though Kathy accompanied him, he felt he was going to die of embarrassment. Dr. Mayberry, however, did her best to put him at ease, taking it all as very natural. She was also very encouraging about the baby. It was developing well, and the ultrasound pictures showed no problems at all. Gradually, it all came together though, and by the middle of the fourth month of his pregnancy, Wanda was as used to his new clothes as he had been to his old ones.

Being at work was simpler. Tracy managed the office. As far as clients were concerned, Adam had taken an extended leave and there was a new woman temporarily replacing him. His morning sickness was now past, and he could concentrate more on his work. Except for those times when he leaned back daydreamed about the baby. By the fourth month, he was definitely beginning to "show," and Tracy bought him a special cushion for his office chair to help him manage the back pain. He also had trouble sleeping, for a while, because of the shift in weight in his body, but managed to find a comfortable position rather quickly. Fortunately, he did not have the gum and nosebleed problems that many pregnant women have. Following Kathy's advice, he ate a calcium-rich diet so that the baby would have strong bones.

He was glad now for the wardrobe of maternity clothes that he had. In fact, he really liked them. He also got used to putting on makeup in the morning, and no longer needed Kathy to help him. Surprisingly, he enjoyed that too, and would occasionally experiment with new and different looks. Kathy had arranged for him to visit a beauty salon; at first he was very apprehensive, but he was treated well there, and by now he was getting to be a regular customer. His regular hairdresser kept on inquiring about the baby and, when the baby started kicking and he allowed her to feel his growing tummy, she almost screamed with excitement and then refused to charge him for that day's treatment. In order to look more feminine, he had tips added to his fingernails and enjoyed looking as his longer, thinner-looking hands with their bright red polish. His toes has the same color, even though it became harder and harder to see them, as his pregnancy became more advanced. But Kathy insisted on applying the polish to them, saying that a woman, even when pregnant, had to look her best.

---

When Wanda entered his third trimester, Dr. Mayberry insisted that he start attending classes for expectant mothers. While it was clear that his baby would be delivered by Caesarian section, and not by natural childbirth, she said that he had to learn about breastfeeding, as well as about the changes he was going to undergo during the final three months. Also, she said, he would learn to bond with other mothers-to-be. Wanda didn't even flinch at that. He was, by now, so used to thinking and acting like a woman, that the term didn't faze him. He didn't even get upset when his mother called him "my blossoming lovely daughter" and warned him to take care of himself, since he was carrying her granddaughter in there. Wanda found breastfeeding classes very interesting. He would definitely breastfeed his baby as long as possible. After all, Dr. Mayberry had assured him that this was no problem and, in fact, had used a breast pump to extract some milk from his (now C-cup) breasts to prove it. He loved the feeling, and at night would dream of holding little Mary-Ellen in his arms and nurturing her. He thought about the baby constantly. When his mother offered to teach him how to knit, he gladly accepted and, by the beginning of his third trimester, had already knitted a quilt for the baby, and was going to begin on some booties. He would sometimes take his knitting to work with him, much to the delight of the other women in the office.

One of the problems of the third trimester was his frequent need to go to the bathroom. Since he started dressing as a woman, he had, of course, been using the women's rest room, but at first had always made sure it was empty before he entered. Now, there were times when he could not afford to wait, and often would rush in while Tracy or Olga were still there. Needless to say, they never said anything about it, even when, once, he came in just as Maria was changing her tampon. He learned to elevate his legs while he was working, and to drink lots of water to avoid dehydration. His belly seemed to be so huge, and growing every day, that sometimes he was sure he would burst. The baby would kick him at the most unexpected moments, and sometimes he nearly lost his balance. Even though he always took Kathy's advice and wore very comfortable and sensible shoes, he felt surprisingly attached to the low heels he had worn during his second trimester. He missed how his legs felt nice and sexy. Tracy assured him that the sexiest thing about a woman is a pregnant belly.

Meanwhile, the workload in the office increased. When it was clear that Wanda could no longer carry his share of the load, Tracy decided to hire another worker to help him handle the Polish translation work. The choice fell on Jerzy Dudek, a recent immigrant from Warsaw with a law degree from there. At first, the others were apprehensive about having a man working in "this hen house," but even Wanda agreed to it in the end, since they could find nobody else. Of course Jerzy was not told that Wanda was anything except a pregnant woman who needed an assistant to carry out her duties. He was expected to help him until he gave birth, and then stay on for a few months while Wanda was on maternity leave. Jerzy was five years older than Wanda and treated him, as everyone else, with an old-world deference that Wanda remembered from when he was little. Jerzy always referred to "Madame Tracy," "Madame Olga," and "Madame Wanda," and would kiss their hand with a very exaggerated motion. He was especially solicitous to Wanda, because of his condition, and would always insist on holding his chair for him and on helping him on with his coat. Often, he would drive Wanda home and, after a while, would be invited in for a cup of coffee as a reward. Wanda had to admit that he enjoyed his attention, and looked forward to it.

When, one day, Jerzy invited Wanda to a concert by the visiting Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra and, before he thought about it much, Wanda accepted. Only later that night, did he gasp when he realized what that meant -- he was about to go on his first date as a woman. Kathy, was delighted. She went with Wanda to pick out a new dress, appropriate both to his condition and to the occasion, and some new shoes and a handbag to go with it. When Jerzy came to pick him up, he brought a large bouquet of flowers and Wanda thanked him with a peck on the cheek -- it just seemed like the natural thing to do. After the concert, when he escorted him home, Jerzy kissed him on the lips. Wanda smiled and returned the kiss. He had had a wonderful evening, and dreamt about Jerzy that night -- not for the first time.

From that day on, Jerzy and Wanda would go out together often. Nothing sexual happened between them beyond short kisses. Jerzy was too much of an old-world gentleman to try anything with an obviously-pregnant woman. Wanda, for his part, forgot that he was not a woman, and just enjoyed being in the company of a nice male companion who flattered and pampered him, with whom he could speak Polish, and with whom he had so much in common.

And then, before he knew it, "the date" approached. Dr. Mayberry was the first to breach the topic. "We have to schedule the birth," she said. "Will a week from Wednesday be OK?" Wanda was shocked and unprepared. "Look at you," said Dr. Mayberry. "If you get any bigger you won't fit through the door. You have a healthy wonderful young girl inside of you and she wants to get out." Wanda burst into tears. "It is all right, honey, it is all right," Dr. Mayberry comforted her. "Go home and have Kathy pack a hospital bag for you. She will know what to put in it, and she will accompany you to the hospital."

On the evening before the Wanda was scheduled to go to the hospital, Tracy, Olga, Maria, and Kathy threw a "coming out" party for the baby. Jerzy was there too, but while all of the women were so excited and made a big fuss, he was surprisingly quiet and sat by himself in a corner, in deep thought. Then, finally, he pulled Wanda aside and asked to talk to her privately.

"Madame Wanda," he said quietly as they sat together on the sofa, "tomorrow you will have your baby. I know that the baby's father is no longer with us, and it will be bad for a child to grow up like that with no father. It is bad and it is wrong. Madame Wanda, you know that you are very special to me. I have been thinking about this a lot, though we have never talked about it. Madame Wanda, will you honor me by being my wife?" Wanda looked at him, his eyes filled with tears ... and he fainted.

It took a few minutes until Wanda came to. During that time, Jerzy retreated, very scared, to a seat in the corner while Tracy and the girls hovered over him. Even though he was not scheduled for his Caesarian until the following morning, Kathy insisted (in her role as resident nurse) that, just to be on the safe side, he had better be taken to the hospital immediately. Dr. Mayberry, when contacted by phone, agreed with her and so Wanda was bundled into the back seat of Kathy's old Ford and driven to the hospital, where he was admitted to the maternity ward and assigned to a private room. Dr. Mayberry was waiting for him, very anxious about the cause of his fainting spell. When Wanda told her what had happened, she laughed, and then asked whether Wanda was going to say yes or not. Wanda's eyes filled with tears, and he didn't answer.

"In other words," Dr. Mayberry said, "you are not rejecting it offhand, are you?"

"I can't say yes," said Wanda. "You know that. But I must admit that I am very fond of him."

"I know no such thing, hon," said Dr. Mayberry. "You are a mother about to give birth to a baby girl. Jerzy is right, the baby needs a father as well as a mother. You cannot be both, and being a mother is more natural for you at the moment. You have become a very feminine woman, because your body created all of those hormones to make the fetus' development possible. That will stop, however, once the birth is over. If you want to continue breastfeeding the baby afterwards -- which I gather you do -- you will have to take hormone shots, and well as injections to increase your milk production. After that, if you wish, it is not that great a step to surgically turn you fully into a woman. Think about it, honey. Think of your daughter's future and yours. But meanwhile, we have an operation to prepare for."

Wanda was very tired and quickly fell asleep. In his dreams, she saw herself in a white bridal dress, walking down the aisle with Jerzy at his side. However, before Father McQueen could begin the ceremony, he was awakened by Kathy and another nurse, who came to prep him for his Caesarian section. They carefully cleaned his huge abdomen with an antiseptic solution. He was moved to a gurney, and taken into the operating room. There, an IV was connected to his arm so that he would have plenty of bodily fluids. He was given a local anesthetic so that he would feel no pain, and his abdominal area was curtained off with surgical drapes. Dr. Mayberry and two others were going to perform the procedure. Wanda remained conscious, but was groggy and soon, almost against his will, dozed off. When he awoke, he was being transferred to the recovery room for post-operative care. The baby was fine and healthy, he was assured, and he would be able to hold it as soon as he felt he was fully alert.

And it happened! Within four hours, Wanda was able to sit up in bed and hold a tiny bundle of joy, little Mary-Ellen, in her hands and clasp her to his breast. The baby, with inborn instincts, began to suck at Wanda's breast, and looked at him with beautiful blue eyes. She seemed to say to him, "You are my mommy; please be my mommy always; I need you." Mother- and-daughter bonding, stronger than the strongest superglue, began to form.

One person who had not been completely happy with the emergence of Wanda was Father McQueen. Although he had approved of Adam's original pregnancy, he had his doubts about the advisability and suitability of Adam living as a women. When that happened, he advised Adam that the best course would be for Wanda to attend a church in another parish, where Adam had not been known previously. Nonetheless, the two remained close friends and Father McQueen would visit Wanda at home once a week, and hear his confession. He was among the first to visit Wanda in the hospital too, and, the moment he saw the him holding the baby and nursing it, he knew that Adam had made a right decision. He and Wanda decided that the baby had best be baptized at the Church which Wanda was now attending, but Father McQueen promised to be present.

In confession, Wanda told Father McQueen all about Jerzy's proposal, and how he had fainted. He asked for guidance, but Father McQueen could not give it. He would consider the matter carefully, and they will talk again. When he left the hospital, he was deep in thought and prayer and, in his head, was already composing a long confidential letter to the bishop, requesting an urgent personal interview. Before that, he knew he had a lot of theological research to do.

Tracy, Olga, and Maria, on the other hand, were totally ecstatic when they first saw the baby. They brought flowers, of course, and Tracy surprised Wanda by bringing a basket of bagels, reminding him that the earliest reference to bagels was in a Krakow manuscript from 1610, which mentions "beygls" as a gift to women after childbirth, though she admitted that nobody really knew if, in that source, "beygls" referred to the food, to a stirrup ("beugal" -- but then traditional Polish bagels are stirrup-shaped rather than round) or to something else altogether. They also brought lots of baby clothes.

Jerzy did not come to the hospital, much to Wanda's disappointment and dismay. He sent a huge bouquet of flowers and a wonderful card, saying that he loved her but would have to wait until she and the baby came home before he came to see them, since he was ill with the flu and did not want to infect the baby. Silently, Wanda cried.

When Wanda did come home, a surprise awaited him. His mother had completely outfitted the spare room as a baby's room, with all of the necessary furniture, piles of toys, and what seemed like a fifty-year supply of disposable diapers (In fact, they were all gone within six months.) The walls were painted a bright pink, and were decorated with pictures of angels.

Wanda needed to do some urgent shopping too. He had no "non-maternity" outfits and it would be clearly inappropriate to go back to wearing his male clothes at this stage. Fortunately, he and Olga were roughly the same size now, and she lent him some jeans and a top before they went off to the mall to splurge, with little Mary-Ellen being watched over by her doting grandmother. If he wondered a bit at how it came about that he was trying on skirts and blouses, all he had to do was touch his breasts, full of milk for his lovely infant daughter, to know in his heart that he was doing the only right thing. He would also admit, off the bat, that he loved the experience. Trying on beautiful clothes when you are pregnant and thinking of only the next few months is quite a different experience from doing it when you have committed yourself, knowingly or not, to the permanence of it all.

A week after Wanda came home, Father McQueen visited him and the baby, and then asked to talk to him frankly about his situation. "What is the most important thing in your life?" asked Father McQueen.

Wanda answered without hesitation, "I want to walk in the ways of my Lord and my Savior, the ways of life and love. I have been blessed to bring a baby into the world, and nurturing and raising her is now the center of my life. I feel that this is my destiny in life at the moment."

"Do you feel comfortable as you are, dressed as a woman, having people relate to you as a woman?"

"I cannot say that it was easy at first, nor that it is the way of life I imagined I would find myself in. There are times when I feel very uncomfortable in this role though, I must say, though, that I am beginning to enjoy it. Perhaps it is a result of the hormones which my body created, but it feels comfortable now, and sometimes fun. However, even if I did not enjoy it -- even if I hated it entirely -- I would sacrifice my own happiness and dreams for those of my baby, and continue on this path."

"Do you love Jerzy?" "Yes, Father, I do. I know that it is a sin for me to love another man, but I do not feel that way. He is a good man, and would be a good parent for Mary-Ellen and would be a good husband to me. I think we both need him and I am sure that I have a large enough supply of love to share with him as well.

The probing continued for over an hour. Father McQueen made Wanda confront his present situation and his feelings about it. Sometimes the same question returned in a different form. Sometimes it came in the form of a challenge. Finally, he was ready to give his opinion. "It is as I thought, and as I presented the situation to the bishop. Yours is a very unique case, Wanda. It has happened because God, in His infinite wisdom, has made available for humans to know the medical technology and knowledge which allowed you to be pregnant with Mary-Ellen to begin with. In His infinite wisdom, he has allowed you to bring your pregnancy to fruition, and has provided you with a beautiful daughter. It is therefore only right and fitting that you make use of other medical technology and knowledge to help raise your daughter, when such technology is available. The bishop and I talked about this and even consulted my old professor of theology at Marquette University, and we came to a rather unusual, but logical, conclusion, and one which seems necessary though it be rather non-canonical. We recommend, Wanda, that you strongly consider Sexual Reassignment Surgery to turn yourself into a legally-recognized woman. Then you will be allowed, in the eyes of the law and the eyes of the church, to marry Jerzy and pursue the life that you two, and your daughter, deserve."

Wanda was, needless to say, totally shocked. The idea of having a sex change had, of course, crossed his mind over the past months, and at one point Dr. Mayberry had brought the idea up as well, though she did not press it. She did point out that the operation has become relatively routine and that there are many fine surgeons available to do it. Moreover, Wanda certainly had the requisite "real life experience" as a woman already behind him, so that if Wanda wanted it, the matter could be arranged with relative swiftness. Still, Wanda had always assumed as a matter of course that the church would oppose such a decision. Here, all of a sudden, his own priest, backed explicitly by the bishop, was not only condoning it, but actively recommending it.

"The church is not as hidebound as people think, Wanda," said Father McQueen, "and it recognizes that special and unusual problems require creative, special and unusual solutions. You have been a very fine son of the church, one of which I am very proud. I am sure you will be a very fine daughter of the church as well. Jerzy is a good Catholic, and a good man. He will be a good father to Mary-Ellen."

The next day, as if on cue, Jerzy came to visit. He apologized for not coming earlier, but had been so worried that he might infect the baby, that he preferred to stay away. He hugged Wanda and kissed her repeatedly, and she returned his kisses. After looking at the sleeping baby, and gingerly holding it, and after half an hour of obviously-strained small talk, he finally came to the point. "Madame Wanda," he shyly said, "before you want to the hospital, I asked you a question. Have you thought of your answer?"

"Dearest Jerzy," Wanda replied, "I first have to tell you something ... you had better sit down."

"No you don't have to, Madame Wanda," he replied, "I already know all about you."

"You know?" gasped Wanda, "How?"

"I am a man of old-fashioned manners, Madame Wanda, as you know," he replied. "Before I even approached you, I talked to your mother, and formally asked for your hand in marriage. That is how things are done in the Old Country. She told me everything."

"And it didn't make any difference?" said Wanda, unbelieving. "No, darling, it didn't. I love you Wanda, and that is all that is important. The other things are details which can be worked out, somehow. The love is what is important."

"I love you too," said Wanda, "and my answer to you is yes, yes, yes, yes!"

And so it came to be. With the help (and even partial funding) of Prof. Harrison and Dr. Mayberry, Wanda was able to have her surgery within half a year. On Mary-Ellen's first birthday, they were married by Father McQueen in a full Catholic ceremony. Wanda was already a mother but, like her mother before her, was nonetheless a virgin when she walked up to the altar and wore her beautiful white dress with pride. As Father McQueen predicted, she was and would always be a good daughter of the church.

AUTHOR'S ENDNOTE This story was written to show that it is possible to come up with a plausible scenario in which a heterosexual male with no transsexual tendencies, coming from a deeply religious and conservative background, would decide to decide of his own free will to become a woman, and do so with the support of the people around him. Magic, domination and force play no part in the tale, and are not needed. Pure love is much stronger than any of them.

Notes:

Want to comment but don't want to open an account?

Anyone can log in as Guest Reader -- password topshelf to leave a comment.

Can-Can

Author:

Organizational:

Audience Rating:

Taxonomy upgrade extras:

A multipart story ...

Can-Can |

|

Can-Can, I

Author:

Audience Rating:

Publication:

Permission:

Can-Can, I Mirror, mirror on the wall, who -- really -- is the fairest can-can dancer of them all? |

|

CHAPTER 1. JEAN

The date is the last decade of the nineteenth century, and the place is Paris, France. More specifically, it is in the 18th arrondissement, at 82 Boulevard de Clichy, in that part of Paris known as Montmartre, notorious for its bohemian lifestyle and abutting on the brothel district of Pigalle. To many of the more cosmopolitan young men in the city, and in all of Europe, this is the center of the world. The name above the big doors is synonymous with their ideal of heaven: MOULIN ROUGE, the most famous music hall of them all! On the roof was the famous facsimile red windmill, and on both sides of the front door are gigantic posters advertising the reigning archangel of that heaven: Marie Lachaud, the can-can dancer extraordinaire, the wet dream of every red-blooded male in France. The posters show her with her gorgeous legs flung high into the air, her skirts swirling about her, her face beaming with a sexually-enticing smile.

But the hour is 4:30 am. The music hall is dark. Jean Daumer, stagehand aged 18 and a half, has turned off the last of the gas lights and has exited by the small green side door, bolting and locking it from the outside. “She is long gone,” he shouts at the dozen or so men in tuxedos, clutching Champagne bottles and mostly quite drunk, who are hoping for a chance to talk to, or even just touch, the fabled Marie Lachaud. They shuffle off reluctantly, as Jean walks down the street and turns to a small café on Rue Cadet, where, in the back room, a group of a dozen or so women are sitting and drinking tea. These are whores who work at the Moulin Rouge and, their work for the night done, gather together in their "parliament" to gossip and compare notes before drifting home to get some sleep.

(Author’s note: I am not being insensitive here. While all languages have many euphemisms for working ladies of the night, among themselves they tend to prefer being brutally simple and open about who and what they are, and always refer to themselves as “whores”. Also, they preferred to drink tea -- or hot chocolate in the winter -- than to touch any alcoholic beverage. Even the madly expensive “special Champagne” which they insisted that their marks order for them from the bar at the Moulin Rouge was, in reality, just colored carbonated cold tea, which the barmen keep in specially-marked bottles. A working girl cannot afford to have her senses dulled by alcohol. Now, after hours, most of them have removed their makeup — which was smudged anyhow after a hard night’s work — and look more like a group of shop women relaxing after long hours behind the counter. Two have even taken out their knitting, which keeps their hands busy during the conversation.)

Jean had been “adopted” by this parliament many years ago, when he was a street urchin of 12 years old, and they became surrogates for his biological mother, who threw him out of her home so that she could have privacy with her everchanging lovers. From the first — and in return for irregular meals — he ran errands and did other small tasks for them. One night, one of the whores, in a moment of distraction and tiredness, talked to him using the feminine gender and he, without a thought, answered her in the feminine gender. That drew a round of laughs and became the group in-joke. From then on, they always talked to Jean as though he was a girl, and he always answered them in the same vein. They called him “Mimi”, and he became like a little sister to them (or daughter, to the older ones).

Jean was particularly attached to Brigitte Leblanc, the youngest of the group. She had run away from her parents’ home in Brest at the age of 15 and a year later, when Jean first joined the group, she seemed to him to be the ultimate in grown-up sophistication. From the start, at 11:00 each morning, he would knock on her door and wake her up. (Where Jean slept nobody knew, and he refused to divulge.) While Brigitte prepared breakfast for both of them, he would wash her delicates in a wash basin in the corner of the room, and hang them on a clothesline to dry. Meanwhile, Brigitte would tell him about her night and clients. Sometimes she would be excited about a new position or other trick she had learned from one of her clients, and insist on demonstrating it on Jean (he would take the girl’s part, and she would act the client’s part). Sometimes she would show him some new jewelry she had managed to get as a present from a client or shoplift at the new and ultra-chic Galeries Lafayette.

For the most part, Brigitte sewed her own clothes and often used Jean as a model to see how they looked and make minor adjustments. Jean liked wearing them in her room, but was reluctant to go out of doors wearing them, saying that he did not feel right in them. One day, Brigitte surprised him by showing him a frock which she had sewn -- one just right for a preteen girl. Jean tried it on and loved it, especially when Brigitte also produced a pair of matching shoes, which she had "procured" at the Galeries Lafayette. They were so beautiful! Reluctantly, he agreed to go out with Brigitte for a walk in the park, wearing his new clothes. Brigitte did his longish hair in a nice bun and applied some makeup to his face (not to much, for he was only a kid) and they both went out together for a stroll. After that, this became part of their routine. After they ate and Jean did the dishes while Brigitte dressed (she slept in the nude and normally walked around her apartment that way; she had no qualms of being nude in front of “her little sister” Mimi), Jean would help her with her makeup and then she would help him dress and do his hair and makeup. They would go out for a stroll in one of the parks or along one of boulevards. Brigitte liked to point out the nice-looking men to “her sister”, and go into extravagant detail about how she imagined they were equipped between the legs, all the while maintaining the poise and expression of a very innocent teenager. Then she would give a very professional assessment of what she could expect from them in bed. Needless to say, it was quite an education for Jean. As Jean grew older, the clothes which Brigitte made for him became more and more adult in style. There were times that he even wore some of Brigitte's old dresses, which need only small alterations since both "sisters" were very close to the same size. Still, Jean was shy and never went out wearing a dress except in Brigitte's company (indeed, he stored all of his dresses in her room). He certainly never wore them to work at the Moulin Rouge, a job which the whores managed to obtain for him after he reached the age of 15.

Under Brigitte's direction, Jean learned how to care for his skin by rubbing it with various creams. He carefully plucked out his facial hair by the roots, when it started growing, and shaved the hair on his arms and legs, after first doing the same to Brigitte. Little by little, he unconsciously began adopting the mannerisms and body language of a teenage girl, much to the delight of the members of the parliament. By the time he was 15, he was so at home behaving and thinking like a girl that, when he went to work as a boy, he had to keep on reminding himself to behave and talk appropriately.

CHAPTER 2. THE DWARF

When Jean came in, the parliament was in the midst of an animated discussion concerning one of its favorite topics of conversation —The Dwarf. The Dwarf was, of course, the painter Henri Marie Raymond de Toulouse-Lautrec Monfa, a chronic habitué of the Moulin Rouge and of all of the brothels in the Montmartre area. His posters of Louise Weber, who created the can-can, made the dance, and the music hall, famous; his current posters of Marie Lachaud exceeded them in their vibrant beauty and life. The Dwarf visited the Montmartre brothels so frequently that he often literally moved into one for days on end, not only enjoying the professional services of the whores but also painting and drawing them during their leisure moments. He was one of the most endearing characters of Montmartre, and on good terms with everyone.

And now The Dwarf was upset, and creating a minor ruckus. It seems that he had taken it into his head that he must paint Marie Lachaud not only as a dancer but also in her moments of relaxation. He had asked her to model in his studio, and she refused. Not only that, she refused to tell him where she lived, or even meet with him anywhere outside of the Moulin Rouge. Now The Dwarf was a bohemian at heart and in lifestyle, but he was also an aristocrat, descended from the Counts of Toulouse. He was not used to being spurned, and was very upset. In fact, this evening he had gone to the office of Josep Oller, the manager of the Moulin Rouge, and demanded that his famous posters be removed. It was only with great difficulty that he was reminded that he had been paid a handsome commission for the posters, that they were now the property of the music hall, and would be removed only when the manager saw fit to remove them. He was also mollified with some free bottles of absinthe.

Of course, The Dwarf was not the only male in Paris who tried, without any success, to snare Marie Lachaud outside the music hall. In fact, nobody knew where she lived or what she did when she was not dancing. This gave rise to rumors that she was really the daughter of a high-ranking family, perhaps even of one of the cabinet members (several candidates were mentioned) or, even, that she was of royal Bourbon blood. Others said that she was the wife of a major banker or industrialist (several names were bandied about) or even the mistress of a cardinal. One story linked her to the American ambassador, either as daughter or mistress. Another story asserted that she was really a nun, who escaped nightly from one of the many convents in Paris. Where Marie Lachaud spent her days was one of the biggest mysteries of the city.

The whores were concerned not with that but with pacifying The Dwarf. If Marie Lachaud preferred her privacy that was her affair, but if Toulouse-Lautrec was in a foul mood, a pall of depression covered the whole of Montmartre. Several proposals were put forth, but the whores could agree on nothing and finally decided that they would have a talk with Rosa la Rouge, a notorious fellow whore who was The Dwarf’s favorite model, to try to figure out a way to overcome his current fixation.

Around 6, the meeting finally broke up and Jean went to the secret hovel where he had his bed. The next morning, as usual, he went to Brigitte’s room, but she was feeling poorly and clearly had a high fever. For several hours, he held compresses to her head and tried to cheer her up with various funny stories he heard or made up. It didn’t work all that well. Finally, he had to head to the Moulin Rouge to begin work. He wasn’t feeling all that well himself, but was sure he would be able to function, at least for that evening.

Jean was, as usual, the first to get to the music hall. He unlocked the side door and entered. After lighting the gas lights in the main corridor, he entered the largest of the dressing rooms and, from the inside, locked the door. Then he began the long and arduous process of transforming himself into Marie Lachaud, to be ready in time for the first performance of the evening. After all, it was part of Marie Lachaud's mystique that nobody ever saw her arrive, just as nobody ever saw her leave.

Can-Can, II

Author:

Audience Rating:

Publication:

Genre:

Character Age:

Permission:

Can-Can, II |

|

(author’s note: This is a direct continuation of Part I, which has to be read first.)

CHAPTER 1. THE END OF A LIFESTYLE

It was not a good performance. Although the vast majority of the audience were ecstatic at Marie Lachaud’s dancing, as usual (but then some of them were so drunk that they would go wild over a dancing iguana), those cognoscenti who were Moulin Rouge regulars realized that the night was far below par. Even The Dwarf left his usual place right in front of the stage and retired to the bar, disappointed and disgusted, before the act was finished. As Jean removed his makeup he realized that his forehead was burning up, just as Brigitte’s had been earlier that day. He barely managed to turn off the gas lights and lock the stage door. Instead of heading to meet the others at the parliament, he went directly to his bed and lay there, trembling, until he fell asleep.

When Jean woke up, it was noon. He was late for Brigitte, and very worried about her health. Quickly, he dressed and went over to her room. When he came there, he was surprised to find all the members of the Rue Cadet parliament there, many of them in tears. One of them took him aside and broke the news to him. “Mimi, cherie, your elder sister Brigitte passed away during the night. She didn’t show up for work as usual, and so we went to see what was wrong. We found her in a very bad state, and managed to pry that old lecher Dr. Maheux away from the bar at the Moulin Rouge and bring him here. By the time he arrived, it was too late — she was gone. Dr. Maheux says it is most likely the influenza which has been sweeping Paris for the past month. He says that hundreds, maybe thousands, have died from it, but the government has ordered the newspapers not to print anything, supposedly to prevent panic but more likely to prevent anyone from questioning the competence of the health authorities.”

Jean looked blank. He tried to cry, but no tears seemed to come. Then he fainted.

When Jean awoke, he found himself lying in Brigitte’s bed, with one of the whores from the parliament sitting by to his side. “You have been sleeping for over 24 hours, Mimi” she said and kissed his forehead. “You had such a high fever, we were afraid that you were on your way to join your sister. Come, let me help you up.” Gently, she helped Jean to his feet and guided him down the hallway to the toilet common to all of the rooms on the floor. Afterwards, she heated some soup on the burner, and fed it to Jean slowly. She put her hand on Jean’s head. “Your fever seems to be lower. You will recover.”

Jean lay in Brigitte’s bed for two weeks, while the whores took turns feeding him and caring for him. They also brought him the news which was creating a sensation at the Moulin Rouge — the great Marie Lachaud had disappeared! She hadn’t shown up for work one day, and nobody knew where she was. Even M. Oller, the manager, had no idea where she could be. He explained to The Dwarf, and others, that he knew no more than they what Marie’s real identity was and where she lived. She had her own key to the back door and arrived early; she was paid every Monday in cash, and c’est tout. She had not given any explanation or excuse for her failure to report to work and, after a week, M. Oller reluctantly ordered the posters of her to be taken down, and be replaced by those announcing another dancer, Olivia d’Evian, who took her place (no pictures yet).

Needless to say, all of the music hall was abuzz with rumors as to what happened to Marie. The general belief was that she, too, was a victim of the influenza epidemic. It was pointed out that several workers at the Moulin Rouge, including two barmen, a waiter, and the stagehand Jean Daumer, were all known to be ill (the whores had reported Jean’s illness to M. Oller, in order to insure that he not be fired). The other barmen and waiters had taken to wearing gauze masks when they served the public. Several of the regular patrons had failed to appear and one of them, retired General Raynaud, had been buried only the day before in a formal public funeral — although the official reason for his death was listed as heart failure, rumor had it that he in fact died of influenza.

Others speculated that Marie had finally been caught by her husband/lover/father/mother superior and prevented from coming. The Dwarf drank himself into a stupor for four days in a row, but now seems to have recovered enough to make sketches of the new leading dancer, for a possible new set of posters (and another hefty commission).

Jean didn’t care. He would not go back to dancing anyway, he was sure of that. The whole adventure had started as a prank, which Brigitte had suggested to him. He had been working at the Moulin Rouge for a few months, and had plenty of time to observe the dancers from backstage. In Brigitte’s apartment, he showed her the steps of the can-can. While the dance is very impressive when seen from the audience (especially if the audience is rather drunk), it is in fact a simple dance to master. It did not take more than a few months of practice for Jean to be able to wag his legs and swing his body like a professional. “Mimi, you should try out as a dancer,” Brigitte teased him. You are better than half of the cows who are on the stage. At first, Jean just dismissed the idea, but Brigitte harped on it again and again until he finally agreed to come to the Moulin Rouge dressed as a girl and ask for a tryout. But he made Brigitte promise that this would be a secret between them. None of the other members of the parliament were to know.

Brigitte sewed a special dress for Jean for the occasion, which was padded so that he appeared to have a large bosom. She also “procured” at the Galeries Lafayette a pair of high-heeled shoes for him, and trained him in how to walk in them. Then, after fixing his hair just right, she had taken him to the music hall and introduced him to the assistant choreographer, who was also a client of hers. When he asked Jean what his name was, Jean blurted out “Marie Lachaud”, the first name that came into his mind. The rest, of course, is history. His audition was sensational and he was put in the chorus line. Within six months, he had moved to the position of lead dancer, and from there to stardom.

CHAPTER 2. THE BEGINNING OF ANOTHER

Although Jean made a lot of money dancing, he did not change his way of life one bit. He gave everything he earned to Brigitte, who invested it in various stocks suggested to her by another of her clients, who worked at the Paris bourse and had access to considerable confidential information. Sometimes, the two “sisters” talked about their future plans and they agreed that when Brigitte reached the age of 30, she would retire from her profession and they would buy a building in Paris, which they would manage as a small rooming house or perhaps a restaurant.

Without Brigitte, Jean felt lost and confused. He had to decide what to do, and was unable to do so. His only support was the Rue Cadet parliament, and he decided to turn to them. When he felt himself ready, he dressed himself in one of Brigitte’s best dresses and, for the first time, walked the streets of Paris as a woman, alone. He arrived at the parliament just as the last of the whores had come in, and caused no little sensation. While they were used to talking to him in the feminine, and calling him Mimi, none of the others had actually seen him dressed as a woman. Needless to say, the whores were both shocked and delighted to see him dressed that way. “Brigitte told us that you occasionally dressed in her clothes,” said one, “but I never thought you would look this beautiful.”

“Well,” Jean said, “we kept it a secret, just as we kept the secret of the name I used when I was dressed like this.”

“Do you mean you didn’t call yourself ‘Mimi’?”

“No,” said Jean, “Mimi was my name when I was with you. At other times, I had a very special name, which I used until now. But now, I will use it always, in tribute to Brigitte.

“And what did you call yourself, if I may ask?”

“I am Marie Lachaud.”

A collective gasp emerged from the parliament, followed a stunned silence. Everybody looked at Mimi carefully and realized that , yes, she was indeed Marie Lachaud — without the dancer’s heavy makeup and costume. “So that is how Marie Lachaud entered and left the Moulin Rouge without being noticed! She was disguised as Jean! Formidable!” Everybody rushed to hug Mimi and kiss her. She had fooled everybody, including — and especially — The Dwarf.

Mimi then told them about the money that she had earned and Brigitte had invested for her. The amount that had accrued was quite large. However, she insisted that everything belong to all of them, and not just to her. The question was what to do with it. Mimi suggested that they buy a building and open a brothel, but — perhaps surprisingly — the parliament was dead set against it. They wanted something more respectable. After several suggestions were put forth and considered, one of the whores suggested that they open an art gallery.

“But we know nothing about art,” Mimi objected.

“We do know somebody who does, though; all we have to do is persuade him to help us.”

“Who is that?”, Mimi wanted to know.

“The Dwarf, of course!” shouted several at once. Suddenly everyone was very enthusiastic about the notion and erupted with ideas. An art gallery — why not? It would be called The Parliament of the Arts, and would be located right here in Montmartre. They would aim at the same clients that they met during the nights — rich young men who would be glad to pay a fortune for a picture of the woman with whom they had spent the previous evening. They would commission the paintings themselves. Everybody in the group agreed to pose for pictures, in the nude if necessary. Mimi would act as manager of the gallery and as the “front woman” for them all. The main problem was finding artists with real talent, and to do that they had to persuade The Dwarf to help them. For that too, they devised a plan.

CHAPTER 3. PATRON OF THE ARTS

The next night, one of the whores took The Dwarf aside and told him she had a big surprise for him, if he would follow her after work. He did not believe her, but agreed anyway, since adventure was something he enjoyed and, in any case, he was still somewhat depressed. So, at 4:30 am, he was led to the back room of the café on Rue Cadet and there, waiting for him, was … Marie Lachaud. She slowly rose and kissed him on the forehead. “My dear Henri,” she whispered, “I had always wanted to meet you, but up until now — for reasons I cannot explain — it has been impossible. The situation has now changed. I have been very ill, as I am sure you have heard, and though I have recovered, I no longer have the strength to dance.”