Josephine's Adventure

Author:

Organizational:

Audience Rating:

TITANIC

Author:

Audience Rating:

Publication:

Genre:

Character Age:

Other Keywords:

Permission:

An Unexpected Journey

My name is Josephine. I live in Großmöllen, in the German Empire, near the coast of Pomerania. I am seven years old, and I am Jewish—Ashkenazi, like all the families on our street. We keep a kosher home, and Mama lights the Shabbos candles every Friday evening. But I suppose that's not the part most people notice first.

They see me and ask, "Is that the boy from the Goldstein family?"

But I'm not a boy. Not to me. Not ever.

I was born Joseph. But even when I was three years old—just learning to speak full sentences—I knew something was wrong with that name. With that life. I told Mama I was a girl. I wanted a girl's name. I wanted to wear dresses and ribbons and help knead challah with the other girls in the kitchen.

Papa didn't like it. He said I was born a boy and must behave like one. He didn't yell, but his eyes would get tight like the string of his fiddle when it needed tuning. I cried and stomped and screamed until I couldn't breathe. I remember that night so well—Mama kneeling by my bed, brushing my hair back, whispering that maybe this was just a phase. "It'll pass," she told Papa later. "Let her have her way for now."

But it's been four years. And it hasn't passed. It won't.

My twin sister, Anneliese, couldn't be happier. She says Hashem gave her a sister after all—just in His own time. We share everything: hair ribbons, secrets, and our favorite game—knucklebones, which we play on the cobblestone stoop outside. Sometimes we chalk squares for hopscotch. Other times, I stay inside with Lucie, my doll. Mama gave her to me for my sixth birthday. She has a soft linen face, blue glass eyes, and long red yarn hair. Her dress is sky blue with tiny hand-stitched flowers. I tuck her beside me every night before I sleep, whispering secrets only she can hear.

The boys in the neighborhood found out I was born Joseph. Since then, they've called me awful things. "Freak of nature," "sissy," "mishugene." They laugh when I pass by, kicking up dust with their boots and pointing. The girls, except for Anneliese, won't speak to me. They act like I don't exist.

So most days, it's just me and my sister. I don't have any other friends.

But I still have Lucie. And Shabbos. And Mama's soft hands brushing mine when no one else is looking.

Date: Friday, the 5th of April, 1912

Place: Großmöllen, German Empire

Time: Half Past Ten in the Morning

Anneliese and I were playing knucklebones in the yard, near the edge of the garden. The sun had warmed the stones just enough to make sitting outside pleasant, and we were halfway through our third round when we heard the sound of wheels skimming the road.

A boy on a bicycle—older than us, maybe fifteen or sixteen—sped up to our gate, tossed a small envelope toward Papa, and was gone again before the dust had time to settle. A telegram.

Whenever a telegram arrives, it's usually from Opa and Oma in Berlin. They send little messages on holidays or birthdays, always signing with blessings for health and long life. So of course Anneliese and I scrambled to the door, eager to hear what they had written this time.

But it wasn't from them.

Papa unfolded the paper. His brow furrowed as he read, and his hands began to tremble.

Mama stepped closer, peering over his shoulder. As her eyes scanned the words, she raised a hand to her mouth—and then the tears came.

Anneliese and I stood in silence, hearts pounding.

"It's from the city," Papa said quietly, though not really to us. "We're being told to leave."

"To leave?" Anneliese whispered.

"Five days," he said. "We are to vacate the home and leave Großmöllen."

For a moment, the whole house went still. Mama turned away, clutching her apron, crying harder now. Papa sat down heavily in his chair, the telegram still in his lap, staring ahead like someone had struck him.

Anneliese looked at me, her eyes wide with fear—and then she ran. Up the stairs, down the hallway, into our room.

I followed close behind, tears already welling up in my eyes.

We threw ourselves onto our beds and sobbed, holding onto each other like driftwood in a storm. When my crying slowed, I sat up and turned to the window.

From here, you could still see the water—gray and calm today, with just a few gulls gliding low near the shore. I stared at it, that familiar stretch of ocean I'd known my whole life, and wondered how I could ever leave it behind.

This was Mama's hometown. It's where Anneliese and I were born.

We weren't just being asked to leave a house.

We were being pushed away from home.

Date: Monday, the 8th of April, 1912

Place: Großmöllen, German Empire

Time: Quarter to Three in the Afternoon

It has been three days since the telegram arrived. Since then, we've packed up nearly everything—though not all of it can come with us. There's only so much you can carry when you're crossing the ocean.

Uncle Bernhard and Aunt Grethe are coming by to take the rest. Mama says they'll keep our things safe until we send word from America, once we've found a place to settle.

Yes—America.

The land of freedom. The land of opportunity. That's what Mama says, though the words feel too big for me to understand. All I can picture is that statue—a lady with a crown and a torch, waiting by the water to greet us. I wonder if she really smiles. Or if she's just made of stone.

Papa says we are leaving the German Empire for good. He doesn't talk much about why, but I can feel the worry beneath his voice when he speaks in hushed tones to Mama after we go to bed. Something about new laws. Something about how things are changing, and not in ways that are good for families like ours.

I had just finished tying the strings on my bag when I heard Papa hurrying up the stairs, his boots loud on the wooden steps. He's always in a rush on days like this—travel days. Leaving days.

"Beeile dich.Wir wollen nicht zu spät kommen!"he called.

Hurry up. We don't want to be late.

He doesn't speak much English—not yet—which Mama says might make things harder for a while. But she's hopeful. She always is.

Just as we finished bringing our bags downstairs, we heard the low rumble of an engine sputtering up the road. Uncle Bernhard pulled into the yard in his high-wheeled motor buggy, tipping his hat as he waved.

Anneliese and I ran to him at once.

"Uncle Bernhard!" we cried in unison.

"Hallo, meine Mädchen!" he said, arms open wide as he bent to hug us both. "All packed?"

"Pretty much," I said, my eyes dropping to the dirt road beneath my shoes. Saying goodbye was harder than I thought it would be.

We loaded into the buggy, and just before I shut the door, I turned to look back at the house—our house—for the last time. The white curtains fluttered in the upstairs windows, and I imagined Lucie waving to me from the bedroom, even though she was already tucked in my travel bag.

I didn't want to leave. I really didn't.

But we had to.

"Let's get this show on the road," Uncle Bernhard said with a grin, shifting gears and pulling away from the gate.

And just like that, we were gone.

We're bound for Cherbourg, in France, where we'll board a ship called the Titanic. Everyone says it's the largest ship in the world—even bigger than the Olympic, which sailed just last year. And best of all, it's unsinkable. Or so they say.

I wonder what it will feel like to stand on something that big and still float.

Date: Monday, the 8th of April, 1912

Place: Belgard, German Empire

Time: Half Past Six in the Evening

"Alleeinsteigen!" theconductor called, his voice sharp over the bustle of footsteps andclattering trunks. "Allaboard!"

We joined the small crowd making their way onto the train platform, the evening air crisp and damp. As we climbed aboard, the scent of coal and oil filled our noses. Papa helped Mama with her bag, while Anneliese and I clutched each other's hands tightly, trying not to get lost in the shuffle.

Our tickets were for third class, all the way at the rear of the train—but that didn't matter. To us, it felt like we were riding in gold-trimmed carriages. We had three seats toward the back, and since Anneliese and I were small enough, we sat together, pressed shoulder to shoulder. It wasn't the softest seat in the world, but we didn't care. We were going to America.

Papa had explained that train travel was the most affordable way to get anywhere. "We're lucky," he told us earlier. "The coal strike just ended, or there might not have been enough fuel to run the lines at all."

He looked tired when he said that. But proud, too—proud that he'd managed to get us this far.

And he had done something else too: he'd spent a little extra for our passage on the Titanic, so we wouldn't have to share a room with strangers. Just one small room, but it would be ours. Anneliese and I would share a bed, which we were already used to anyway. Better that than sleeping beside someone we didn't know—especially on a ship full of people from all over the world.

Once we found our seats, the conductor came down the aisle, long coat brushing the edges of the narrow path between benches. He took our four tickets with a polite nod, punched neat holes into each, then returned them to Papa with a quiet, "Danke schön."

The train gave a lurch, and we were off.

Anneliese and I jumped up at once, racing to the windows and watching as the world outside began to blur. Trees and cottages zipped by in streaks of green and brown. Horses in the fields turned their heads as we passed. We waved even though we knew they wouldn't see.

"I wish I could see the ocean," I sighed, resting my chin on the edge of the window.

"Why?" Anneliese asked. "We'll see the ocean when we get on the Titanic."

That made me smile. She was right. But still... I wanted to see it now. Just a glimpse.

After a while, the passing scenery began to look the same—more trees, more houses, more fences. I sat back in my seat, and Anneliese followed, plopping down beside me with a happy little bounce.

"This is fun," she said, her voice light as air.

"I agree," I said, nodding. "But I wish there was more to do than just sit or stare out the window. Did you bring any games?"

Anneliese reached into her little cloth satchel and pulled out a small velvet pouch. "I brought jacks," she whispered.

I laughed softly. "We can't play that on a moving train. The ball will roll away, and we'll never find it again."

I looked up toward the baggage rack above us. "I put my chalkboard up there. We could play tic-tac-toe, if we can get it down."

I glanced at Mama, who was seated a few rows ahead, speaking gently to a man in the next seat. He looked kind and had a travel-worn coat. From what I overheard, he was going to Cherbourg as well. And like us, he would be boarding the Titanic.

I began to wonder—how many of these passengers were headed there too? How many people on this train would be with us at sea?

Papa was sitting across from us, leaning over a little wooden board playing chess with a man who wore spectacles and smelled faintly of pipe tobacco. Judging by Papa's pleased smile and the other man's frown, I think Papa was winning. I didn't dare interrupt him. I didn't even know how to play chess.

I giggled as I bounced in my seat. Anneliese was bouncing too, and it made her hair puff up and down like a wool hat being fluffed. I burst into a fit of quiet laughter.

"Stop that," I whispered. "You're making me dizzy."

She grinned and nudged me gently with her elbow. "Only a little dizzy?"

"Very dizzy."

I curled up beside her, hoping the train's rocking motion would help me fall asleep later, not make me sick. The rhythm of the wheels on the tracks—clack-clack, clack-clack—was starting to feel like a lullaby.

We were on our way. Not just to Cherbourg. Not just to a ship.

But to something completely new.

Date: Tuesday, the 9th of April, 1912

Place: Berlin, German Empire

Time: Quarter to Five in the Morning

Somehow, I must've fallen asleep.

The rhythm of the train must have rocked me into it, even if I can't remember when I drifted off. When we arrived in Berlin, it was still dark outside, and everything felt too quiet, too gray. The kind of gray that comes before the sun rises but after the warmth of dreams is already gone.

Papa shook us gently. "Aufwachen," he whispered. "Wake up. We need to change trains."

I rubbed my eyes and whined, "I'm tired." But there was no time for rest. Our connection to Cherbourg wouldn't wait for sleepy children.

We stepped off the train into the cold April air. My hands were stiff. My shoes felt heavier than before. As we crossed to the next platform, a uniformed man stepped in front of Papa and held out a hand.

Papa stopped and began digging in his coat pocket. I watched as he handed over a set of papers—documents and little booklets, the kind that had our photographs glued inside and stamps all over them. Next, they asked to look through our bags.

I clutched mine tightly at first, confused. "Why are they looking in my bag?" I asked.

"They're looking in everyone's," Mama replied softly. "They want to be sure no one is bringing anything forbidden across the border."

"What would we bring that's forbidden?" I asked again.

She didn't answer that time. Her lips pressed into a line, and her eyes stayed on Papa.

Once the inspection was over, we were allowed to board the next train. As before, our seats were in the last car—the third-class compartment near the rear. The benches were stiff and the windows smudged, but at least it was warm inside.

I climbed into the seat, peering longingly toward the front of the train.

"I wish we were up there," I murmured, gazing at the second-class carriages ahead. "They look so new... and clean."

Papa heard me but didn't say anything. I think he wished it too.

The train began to move again. This time, the conductor didn't come to check our tickets. I wondered if that meant something was different—or if maybe they already knew who we were.

The city was still waking up. As the train pulled away from the Berlin station, the early light began to spill through the windows, casting a golden glow across the rooftops. For a moment, the whole city looked like it was made of gold—like it had never known night.

There were people everywhere. Men pushing carts. Women sweeping stoops. Boys chasing each other down alleyways with paper caps on their heads. The buildings were tall, proud, stacked beside one another like dominoes in a row.

But soon, the tall buildings gave way to low houses, then to farmland. And then—

"Sheep! And goats!" I cried, pressing my face to the glass. "Look, Anneliese!"

"Nothing to write home about," a woman across from us muttered, hardly glancing up from her knitting. Her needles clicked steadily as she worked a pale gray yarn.

Her needles clicked steadily as she worked a pale gray yarn

Date: Tuesday, the 9th of April, 1912

Place: Cherbourg, France

Time: Five Minutes to Eight in the Evening

"Did we make it to Cherbourg?" I asked, rubbing sleep from my eyes as the train hissed to a stop.

"Yes, mein Kind, we did," Mama replied softly. "This is your first time outside the German Empire."

I blinked in surprise, then gasped. "Really? We're not in Germany anymore?"

"No, we're in France now," she said, brushing a bit of lint from my coat. "A whole new country."

I couldn't help it—I squealed with excitement. The idea of being in a brand-new land made me feel like a character in a storybook. I looked around as we stepped off the train, expecting something magical.

Instead, I felt a raindrop land on my cheek.

"It's raining!" I groaned, pulling my shawl tighter. The sky above was a sheet of dark gray, and the station's roof did little to keep the water out. Puddles were already forming along the cobblestones outside. I could tell from the look on Anneliese's face that she didn't like the rain any more than I did.

"Since we arrived a day earlier than expected," Mama said, pulling her scarf tighter around her neck, "your Papa and I will look for a place for us to stay tonight."

So we walked—Mama, Papa, Anneliese, and I—through the damp streets of Cherbourg. The gas lamps flickered, casting long shadows over slick stones. The buildings looked old and proud, with narrow windows and signs written in French, which I couldn't read.

We tried every inn we passed, but every place was full. The rooms were taken, and the clerks looked tired and impatient.

"No vacancies," one said without even looking up. Another simply shook his head.

After the fifth or sixth rejection, Mama sighed. Her voice was steady, but I knew she was disappointed.

"We'll have to go back to the station," she said quietly. "It's the only shelter left."

By the time we returned, we were all soaked through. My dress clung to my legs, and my shoes squished when I walked. The station smelled of wet stone, coal smoke, and too many people.

I found an empty bench near the wall and sat down, shivering. Anneliese sat beside me, and we huddled together under our coats, trying to stay warm.

"It's not much," Mama said, brushing water from my hair, "but it will have to do."

That's when I saw it—a flash of movement near the edge of the station wall. A rat darted across the floor, its tail trailing behind like a string. I nearly screamed, but swallowed the sound. No one else had seen it.

"I'm cold," Anneliese whimpered, curling against me.

"Me too," I whispered back. "And hungry."

Papa must have heard us, because he disappeared for a little while and returned with a small bundle of food wrapped in brown paper. He had bought it from a vendor near the station doors—a bit of dark bread, some boiled potatoes, and two small apples.

It wasn't much. But it was warm. And right then, it was enough.

As we ate, people passed us by without a glance, like we were invisible. Wet, tired, and sitting on a wooden bench with food in our laps—we must've looked like ghosts.

But after a while, some people began to notice us. A woman whispered to her husband. A man nearby gave us a long look before turning away. The whispers grew. I couldn't understand what they were saying—French, I think—but it was clear they were talking about us.

The noise in the station grew louder. It seemed the whole world was passing through at once—voices in every direction, carts creaking, footsteps echoing through the stone arches. I saw Mama and Papa listening, trying to catch bits of the conversation.

But I didn't care anymore. My head was heavy. My eyes burned. And despite the noise, despite the cold, despite the rat and the hunger and the strangers watching us...

Anneliese and I lay down on the bench—our coats wrapped around us, heads nestled together—and we fell asleep almost instantly.

Date: Wednesday, the 10th of April, 1912

Place: Cherbourg, France

Time: Six o'clock in the Evening

We spent the day near the harbor, not far from the train station. The rain hadn't quite stopped, but it had lightened into a soft drizzle—just enough to dampen our coats and turn the streets to mud.

The hours dragged by. Every time a ship's horn echoed in the distance, I perked up, hoping it was the Titanic, but Papa would shake his head and tell me, "Not yet."

Now, finally, it was almost time.

The ship was due any moment—thirty minutes, Papa said, checking the pocket watch he always kept chained to his belt. But before we could board the ferry that would take us out to her, we had to go through an inspection.

There was a queue of families ahead of us, all looking tired and travel-worn, some with crying babies, others clinging to sacks of belongings tied shut with string.

We were checked first for illness—Papa said they didn't want anyone with fevers, or coughing fits, or anything that might spread aboard ship. Then a man in a white coat began looking through our hair and behind our ears. He held a small light, peering close. I froze.

What if they checked everything?

I turned quickly to Mama, tears already starting to prick my eyes.

"I don't want them to see... my boy parts," I whispered in a panic.

Mama knelt down beside me, brushing a lock of hair from my cheek. "Shh, Josephine. Don't worry," she said, gently rubbing my back. "They won't ask to see that. Just stay still. It'll be over soon."

I nodded, swallowing hard, and let the man finish. He barely looked at me.

Then they began searching our bags again—something I had become used to by now. I watched as they poked through the clothing, lifted Lucie from the bottom of my satchel, gave her a curious glance, and put her back.

When it was done, they handed Papa a stamped paper and told us we were cleared to board the tender—a ferryboat that would carry us to the great ship waiting just beyond the breakwater.

We stepped aboard with dozens of others, huddling together on the deck under the drizzle. The air was full of voices, French and German, some English too. Babies cried. A woman beside us clutched her rosary tight, whispering prayers under her breath. It was loud. Crowded. Smelled like coal smoke and wet wool.

"It's crowded," I said to Anneliese, squeezing her hand. "There must be a hundred people on here."

Before she could answer, a thunderous blast shook the air.

I jumped so hard I nearly dropped Lucie.

Then I heard Anneliese gasp, "Look, Josephine!"

She pointed out toward the sea.

And there—rising out of the mist and the fading light—was a ship so vast, so grand, so impossible, it made my breath catch.

I turned slowly, my heart pounding.

The funnels reached into the clouds. The hull was a mountain of black iron. The lights gleamed like stars strung along her decks. The ferry rocked slightly as the great vessel came into view, accompanied by smaller tugs and whistles.

I screamed the name before I could stop myself.

"TITANIC!"

TITANIC -2

Author:

Audience Rating:

Publication:

Genre:

Character Age:

Other Keywords:

Permission:

All A-Bored

Date: Wednesday, the 10th of April, 1912

Place: RMS Titanic – Cherbourg Harbor, France

Time: Five Minutes Past Eight in the Evening

We didn't go straight to our cabin when we boarded the Titanic. Instead, we lingered out on the well deck, watching the lights of Cherbourg shimmer across the harbor like stars dancing on the water.

It was already dark. The lamplight along the shoreline glowed orange through the misty drizzle, fading slowly as the distance between ship and land began to grow.

Most of the other passengers were hurrying past us, eager to find their cabins and unpack. But a few stood like we did—quiet, still, caught in the moment.

"Isn't it a beautiful view?" Mama asked, resting her hands gently on our shoulders.

"Yes," Anneliese and I said at the same time.

We didn't get many chances to watch ships leave port. Back home, we only ever saw them pass by Großmöllen—fishing boats and merchant steamers crossing the Baltic Sea. But never anything like this.

As I stared out at the water, I thought about our house. The small garden. The windows that faced the sea. I thought of Oma and Opa, and of the things we left behind—things that wouldn't fit in our bags or follow us across the ocean.

I felt sad. But also... something else. A strange flutter in my stomach that might've been hope.

The wind picked up as the Titanic eased away from the docks, making the night air colder. Maybe it was just the ship's own motion—cutting through the water like a giant iron palace.

"We should go below," Mama said softly. "Land's out of sight now."

We turned toward the companionway. Papa had already started ahead and was speaking with two men near the rail. I didn't know what they were talking about. Mama led us onward, Anneliese trailing behind with slow, reluctant steps.

We began to descend the stairs.

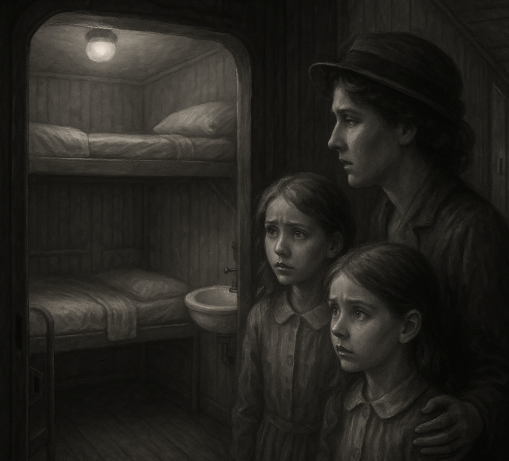

Down we went. Past D Deck. Then E Deck. Then F. Then... G.

Anneliese wrinkled her nose, and I didn't blame her. The farther we went, the colder and damper it became. The paint on the walls looked old and chipped. A few rats scurried across the lower landings, vanishing into cracks like ghosts. I don't think Mama noticed—or maybe she did and pretended not to.

At the bottom of the stairwell, Mama opened a heavy door, and we stepped into a long corridor. The ceiling was low. The lamps gave off a yellow, flickering light that made the walls look sickly.

Rats again. At least three of them, weaving through the shadows like they owned the place.

"This must be it," Mama said, stopping beside a small wooden door. "Cabin G-4."

The hallway was so narrow, I could touch both walls at once if I stretched my arms out. All the doors were close together—lined up like buttons on a coat.

I wasn't surprised by the size of the cabin. Not after seeing how cramped the corridor was. But still, I had hoped for something a little nicer. Something more... grand. This was the Titanic, after all.

Inside were four narrow bunks—two on each side—with thin wool blankets tucked tight. There was a washbasin bolted to the far wall, with a cracked mirror above it.

There was a washbasin bolted to the far wall, with a cracked mirror above it

I looked around, confused.

"Where's the water closet?" I asked quietly.

Mama didn't answer right away.

Do we have to share with strangers? I wondered, suddenly nervous.

"Are you sure this is our room?" I asked, peering inside. "It looks like a closet."

"Josephine!" Mama scolded me, her tone sharp but tired.

I stepped into the room and sat on one of the narrow bunks. Anneliese followed behind me and sat down beside me without saying a word.

I looked at her. I could tell she was sad.

"I know how you feel," I whispered. "I'm sad too. But once we reach America, Papa will find us a new home. And then... maybe things will feel normal again."

She gave me a little smile—but I could tell it wasn't a full one. It was the kind of smile that tries to be brave even when your heart is still heavy.

Mama was standing just outside the cabin door, speaking with a woman near G-6. Curious, I wandered over and wrapped my arms around her waist. She rested a hand gently on my head.

"Josephine, this is Mrs. Agnes Sandström," Mama said. "She lives in America—in a place called San Francisco, California."

"Really?" I said, wide-eyed. "I heard people moved there because of all the gold."

Mrs. Sandström laughed softly. "Yes, that's true. My husband, Hjalmar, and I moved there four years ago—though the gold rush was long over by then. Most of it was found back in the '90s."

She didn't look very old—maybe a little older than Mama. I guessed she was in her early twenties, just like my parents.

"Why were you in Europe?" I asked without thinking.

"Josephine!" Mama hissed under her breath. "It's not polite for a young lady to ask personal questions."

But Mrs. Sandström smiled kindly. "That's quite all right," she said. "My daughters and I were visiting my parents in Hultsjö, and some dear friends in Forserum."

I blinked, confused.

"Sweden, my dear," she added with a gentle laugh.

"Oh," I nodded, though I still wasn't exactly sure where that was.

Just then, I glanced back toward our cabin and saw Anneliese sitting on the floor, playing jacks by herself.

I politely excused myself and returned to our small, narrow room. Mama stayed to chat with Mrs. Sandström a little longer.

"You know," I said, plopping down beside Anneliese, "it's not much fun playing jacks by yourself."

"I know," she sighed. "But what else is there to do?"

I gave her a small grin and joined the game.

A few minutes later, just as I reached Sixsies, the door opened and Papa stepped in, followed by Mama.

"Great news, everyone!" Papa said, his voice full of excitement.

Anneliese and I looked up. I was so startled, I dropped the ball—and it bounced right through the door.

Mama caught it just in time before it rolled out into the corridor.

"What is it, Papa?" Anneliese asked.

"I got a temporary job—here on the Titanic," he said proudly. "I start tonight."

"That's good, Papa," I murmured. "But... what's so great about that?"

"Josephine!" Mama snapped. "You've been very rude tonight."

I lowered my head. "I'm sorry..."

Papa chuckled gently. "Well, Josephine," he said, crouching a bit to meet my eye. "The good news is that because I'm now working on the ship, the captain has moved our family from third class... to second class."

Anneliese and I gasped in unison.

"Really?!"

We both leapt up and cheered.

"That's truly wonderful, dear!" Mama said, clasping her hands. "What kind of work will you be doing?"

"I'll be in the boiler room, shoveling coal," Papa said with a proud smile.

"Isn't that a dirty job?" I asked.

"Yes," Papa laughed. "But remember—we're going to second class."

~o~O~o~

As we prepared to leave third class, Mama stepped over to say goodbye to Mrs. Sandström, who smiled warmly and hugged her goodbye.

"I'm very pleased for you," she said, genuinely happy. "Second class will be more comfortable for the little ones."

Mama thanked her, and I noticed how calm Mrs. Sandström remained. She truly didn't seem to mind staying in third class, even with strangers in her cabin. "They're Swedish as well," she had said with a shrug. "It feels like home."

I wondered what it would feel like to belong so easily, even in a place so far from where you came from.

We made the long walk from G Deck up to E Deck, climbing stair after stair with our bags in hand. Each flight felt heavier than the last—my legs ached, and my bag kept bumping against my knee—but I didn't dare complain. Something about the air felt different the higher we climbed. Less damp. Less stale. Brighter.

The wood paneling on the walls became smoother. The lights were steadier. The people we passed looked a little more rested, a little more polished, though many still wore simple clothes like ours. There were children too, though they looked quieter somehow—like they had been told to behave differently in this part of the ship.

When we reached Cabin 51 on Deck E, Papa slid the key into the lock and pushed the door open.

My eyes widened.

The room was still small—nothing like the grand cabins I'd imagined for first class—but it was bright and clean, with white painted walls and crisp linen sheets. There were two beds instead of bunks, a small writing desk by the porthole, and even a washstand with fresh towels folded neatly on the side.

I ran straight to the bed and flopped down face-first.

"This is the life," I thought dreamily.

It felt like sleeping on a cloud after the narrow, stuffy hallway of G Deck.

Anneliese giggled and jumped onto the other bed, making the springs creak. We didn't even bother to unpack. We were too tired. Too warm. Too content.

It didn't take long for sleep to find us—there in a foreign country, on a ship the size of a city, rocking gently on the sea.

Somewhere behind us, Cherbourg had disappeared. Somewhere ahead, America waited.

And in between, for just a little while... we were safe.

Date: Thursday, the Eleventh Day of April, 1912

Place: Titanic – Second-Class Dining Saloon

Time: Five Minute Past Eight in The Morning

When we woke up the next day, we all felt refreshed and ready for the day—especially for breakfast. As we headed to the dining room, Papa was just coming back from his overnight shift in the boiler room. He looked filthy and definitely needed a bath. You could say he almost looked like a... well, Papa had so much coal dust on him, his face and arms were completely black. It made me laugh.

"You children go ahead and eat breakfast while I get washed up," Papa told us as he walked toward the washroom. "I'll be out later."

As he passed a well-dressed lady heading into the dining room—someone who looked like she belonged in first class with all those fancy clothes—she glanced at Papa with a look of disgust and walked away, muttering to herself.

"What's wrong with her?" I asked Anneliese.

"Beats me," she answered.

We walked into the dining room. Many people were already there, sitting at long tables. It looked almost like a restaurant, with servers walking around bringing out plates. It wasn't too fancy, but it was nice—and perfectly fine for us.

As we sat down, a waiter came over and handed us a menu.

"What would you young ladies like for breakfast?" he asked.

Being called a lady made something flutter happily in my chest. It felt... proper. Like maybe I really belonged here.

I looked down at the menu. "Oh! You have soda scones?" I said with a smile.

"I'm terribly sorry, miss," he replied. "We've just run out."

"Oh dear..." I pouted. "Well, I suppose I'll have the buckwheat cakes instead."

"A fine choice, miss," he said, jotting it down on his notepad. "And would you like some ham and eggs with that?"

"Just eggs, please. No ham—I'm Jewish," I said plainly. "And can I also have a bowl of oatmeal with fruit?"

"May I," Mama corrected gently.

I looked at her, then back at the waiter. "May I have a bowl of rolled oats and fruit, please?"

"Certainly, miss," he said with a smile, then turned to Anneliese. "And what would you like, dear?"

"I'll have the same as my sister," she replied softly.

Mama looked up from her own menu. "I'll have the fish, a bowl of hominy, and a cup of tea, please."

Mama doesn't eat much. She says she likes to keep her figure.

(Whatever that means.)

"I'll have tea as well," I added.

"Me too," Anneliese said, barely above a whisper.

"I'll bring those right out for you," the waiter said before walking off.

I glanced around the room. Other tables were already being served their breakfast. I supposed they must've arrived before us.

Papa came into the saloon just as our food arrived. He placed his order—grilled ox kidneys (which sounded dreadful), some au gratin potatoes, fish, and a cup of coffee. He must have been terribly hungry after working all night.

By the time we'd finished eating, the staff had already begun clearing the tables and preparing the room for lunch.

That's when we heard the ship's horn echo through the dining hall.

Date: Wednesday, the Eleventh Day of April, 1912

Place: Titanic – Queenstown Harbor – Queenstown, Ireland

Time: Thirty-four Minutes Past Eleven in the Morning

The horn we heard meant we had reached our final stop before heading out to sea. I asked one of the passengers nearby where we were, and he said the place was called Queenstown, Ireland.

I didn't know where Ireland was. I imagined it must be full of green hills and sheep, but I wasn't sure. I started skipping off toward the deck to get a better look at the harbor.

"Hey, kid!" a man's voice called out.

I turned to look. He was standing a little ways off, near the railing.

"Shouldn't you be down in third class?" he shouted.

"No!" I yelled back. "I'm in second."

He sneered. "You don't look like a second-class passenger. Go back down where you belong."

His words hit me like cold water. My eyes filled with tears, and I turned and ran, not stopping until I reached our cabin.

"Mama!" I cried as I burst into the room. "This mean man told me to go back to third class!"

Mama looked up from her sewing, alarmed. She stood and pulled me into a hug.

"He said I didn't look like I belonged in second class," I sobbed.

"The nerve of that man," Mama said sharply. "You are a second-class passenger, Josephine, and don't let anyone make you feel otherwise."

She pulled me close, gently patting my back. Then she reached for her hairbrush, sat me down, and began to brush my hair with careful strokes. From her trunk, she pulled out a pale ribbon and tied it neatly into my hair.

I wasn't sure if she was doing it to make me look more like I belonged in second class, or just to make me feel better. But either way, I liked it. It felt soft and pretty.

Anneliese came over, holding out her brush. "Can you do mine, too?"

Mama smiled and nodded.

When she finished, she turned to me and said, "Now Josie, if anyone gives you trouble again—anyone—go straight to a crew member, do you understand?"

I nodded.

"If you want," Anneliese offered, "I can go out with you."

I gave her a quiet smile and nodded again.

"Don't do anything I wouldn't do," Mama said with a laugh. "And be back before dinner."

Anneliese and I stepped back out onto the deck, the sea breeze tugging at our sleeves. We stood together near the railing, watching the small tender boats making their way from shore to ship, each one bringing new passengers aboard Titanic.

Date: Wednesday, the Eleventh Day of April, 1912

Place: Titanic – Queenstown Harbor – Queenstown, Ireland

Time: Fifteen Minutes Past One in the Afternoon

After about ten minutes of staring out at the water, Anneliese and I decided to explore the ship. We couldn't go everywhere, of course—there were areas marked off for first-class passengers only—but we still had fun seeing what we could.

Toward the stern of the ship, we spotted two children about our age. A boy and a girl. They looked cheerful, laughing together as they played some sort of game.

We walked over to them.

"Hi," I said as we got closer.

"Hello!" the girl replied with a smile. "I'm glad there are more children aboard. My name's Marjorie."

"I'm Josephine, and this is my twin sister, Anneliese."

"Hi," Anneliese said softly, her voice a little shy.

"What game are you playing?" I asked, watching the boy toss a rope ring across the deck.

"Quoits," he said as the ring landed neatly on a painted circle with a number on it.

"Never heard of it," I said, tilting my head.

"Never heard of it?" he laughed. "Where in the world are you from?"

"Großmöllen," I answered.

"Where's that?" Marjorie asked.

"Großmöllen is in the German Empire," I said with a small frown. "But we don't live there anymore. We're moving to America. We had to leave our home."

"Oh... I'm sorry," Marjorie said gently. "My mum and dad and I are moving to Idaho, from England. We're going to live near family."

"We haven't decided where we'll settle," I told her. "Probably—"

Just then, the ship's horn blared loudly across the harbor, and all four of us jumped. A few seconds later, we felt it: the subtle shift beneath our feet as the Titanic began to move.

"I suppose we're off," the boy said. "I'd better head back inside. Dinner's starting."

He turned to run.

"Wait!" I called after him. "What's your name?"

"Marshall... Marshall Drew!" he shouted over his shoulder. And then he was gone.

"I'd better get going too," Marjorie said. "I don't want Mum and Dad waiting."

She gave us a little wave and hurried off.

Anneliese and I walked back toward our cabin. Mama was waiting by the door when we arrived.

"You two have a good time?" she asked as we stepped inside.

"Yes," Anneliese said. "We met some children."

"That's lovely," Mama smiled. "Now come along. Let's get ready for dinner."

TITANIC -3

Author:

Audience Rating:

Publication:

Genre:

Character Age:

Other Keywords:

Permission:

Sick in the Head

Date: Thursday, the Eleventh Day of April, 1912

Place: Titanic – Second Class

Time: Seven Minutes Past Two in the Afternoon

After dinner, I went back out onto the deck to see if Marjorie or Marshall were out playing again.

They weren't.

I wandered to the front of the ship and looked out across the sea. All I could see was water—no land at all. Just open ocean. But then I saw them.

Dolphins.

A whole group of them, swimming just ahead of the ship.

They seemed to be following us. I stood there for a long time, watching them jump in and out of the waves. They were so fast, I couldn't believe how well they kept up with the Titanic. I didn't know much about speed—maybe we were going fourteen knots? I wasn't sure. But however fast we were going, the dolphins didn't seem to mind.

They jumped in groups—three, six, even fifteen at a time. Sometimes one swam alone, but it always found its way back to the others. That made me smile.

I really like dolphins. I've never understood how anyone could kill them for food.

They were so graceful the way they leapt through the waves, taking quick breaths before disappearing below the surface again. With each splash, the sea shimmered around them. The ship's bow threw up sprays of foam, making it all look like some kind of watery ballet.

Eventually, like all lovely things, the dolphins drifted off—disappearing behind us as the ship moved ahead.

I waved goodbye.

"I wish they had stayed," I whispered.

The wind picked up as the Titanic gained speed. I felt it rush through my hair and stretched my arms out, letting the breeze lift me.

I felt like I was flying.

"This is the greatest thing ever!" I shouted into the open air.

But just then, a strong gust of wind pushed me forward. I stumbled and had to grab the railing quickly to keep from falling.

"Careful there, kid!" someone shouted.

I turned and saw a man standing a little ways off, looking at me.

"Don't get too close to the edge," he said as he walked over. "You might fall."

He smiled. "What's your name?"

I looked down. "My Mama told me not to talk to strangers," I mumbled.

He chuckled. "You have a very smart mother."

I stepped away, still unsure. I turned and walked back toward our cabin. When I glanced behind me—he was gone.

Just vanished.

I kept walking, not knowing he had followed me for a short while, and then disappeared into the crowd.

Back in our cabin, Mama was sitting near the window, knitting. Most likely another sweater—for me or for Anneliese. Speaking of Anneliese, she was napping, curled up with Lucie. I like naps too, but I wasn't tired. Papa was asleep in the bunk across from me, and I didn't want to disturb him.

"Mama," I whined softly. "None of the other children are outside playing. I'm bored."

"Why don't you read a book?" Mama suggested, still focused on her stitches.

"A book?" I laughed. "Where am I supposed to find a book on a ship?"

"There's a library, you know," she said, amused.

I blinked. "Wait... there's a library?"

Mama chuckled. "Yes, it's on C Deck, near the rear of the ship. The area's called the poop deck."

My eyes widened. "Really?"

She nodded. "If you get lost, just ask a crew member."

That part confused me. Mama always said not to talk to strangers, but now she was telling me to ask one for help? I stared at her. She gave me a small smile, as if she could read my thoughts.

I guess she trusted I'd know when to speak—and when not to.

As I stepped out of the cabin, I saw something move—a quick shadow down the hallway. I paused, then shrugged it off and kept walking. The hallway stretched long in front of me. I figured if I kept walking straight, I'd reach the end of the ship, then head up two decks from there.

As I walked, I started to notice the details—the wood carvings, the gold trim, the softness of the carpet beneath my shoes. The red squares had little crosses in the center. Everything looked like it had been made by someone very skilled—chisels and hammers and careful hands. I thought to myself, People are going to talk about this ship for years. Maybe forever.

It took me a little over five minutes, since I kept stopping to look at everything. Eventually, I reached a staircase and climbed slowly upward. As I turned onto the landing, I nearly bumped into an elderly man making his way down.

He smiled politely, and I stepped aside so he could pass.

At the top of the stairs, I saw it.

The library.

It was tucked neatly into the corner of C Deck—a warm, quiet room filled with bookshelves and big windows that looked out to sea.

I stepped inside.

It wasn't crowded—just a few passengers sitting with books in their laps, or writing postcards. I wandered over to a shelf near the wall, running my fingers along the spines of the books.

So many titles I recognized: The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. The Last of the Mohicans. Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. David Copperfield.

It was hard to choose.

Then I saw it.

Moby-Dick.

The cover had a drawing of a whale, rising out of the ocean. It felt right—reading a sea story while riding the biggest ship in the world.

I opened the book and read the first line aloud under my breath:

"Call me Ishmael."

I wrinkled my nose. "Ishmael? Who would name their child that?"

I kept reading.

"Someyears ago—never mind how long precisely..."

I smiled. Now this was going to be interesting.

~o~O~o~

The book was fantastic. I laughed a few times, especially when things got silly. I was just about to turn the page and start another chapter when I looked up—and saw him.

The man from earlier.

He was sitting just across the room, one hand resting in his lap, the other cradling a cup of tea. He was gazing straight at me.

"Hello," he said, smiling.

"Hi," I replied, quietly.

"My name is Peter Good Man—" he cleared his throat. "Goodman."

He shifted slightly in his chair. "I know I asked your name earlier, but I figured... I wouldn't be a stranger if I told you mine first."

"I'm Josephine," I answered.

"Well, hello there, Josephine. That's a very pretty name."

"Thank you," I said, grinning. "I picked it out myself—"

My voice caught in my throat.

Peter tilted his head. "Hmm?"

"Er— I mean, my Mama picked it," I said quickly, looking down. "She always chooses nice names."

"That's what mothers do best," Peter chuckled.

There was a pause. Then he leaned forward slightly. "I can tell you're bored. Want to come out on the deck? We could play a few games of Quoits. Maybe Shuffleboard. Something fun."

"I'm not bored," I said politely. "I'm reading a book."

He leaned over and read the spine. "Moby-Dick. Oh. That one's about a whale, isn't it?"

"Yeah, it's getting really interesting," I said, lighting up. "Captain Ahab is really—"

Peter raised an eyebrow. "What's so interesting about a book?" he asked flatly.

I blinked. "Well—lots of things. You see, Captain Ahab is really after this white whale, and—"

"You can read that anytime," he said, waving it off. "You're only on this ship for a few days. Come on, enjoy it while you can."

I looked at the book... then back at him.

"...Okay," I sighed.

I gently closed the cover and returned it to the shelf. Then I followed him out of the library.

"You won't regret it," Peter chuckled as we stepped into the corridor. "You'll like the games I'm going to play with you."

As we walked, he reached for my hand.

I let him take it.

People we passed in the hallway probably thought I was his daughter. I blushed a little at the thought.

~o~O~o~

Peter brought me to the Promenade Deck, where he showed me a game using a long stick with a curved end. There were wooden disks lined up near the railing, and a painted triangle on the deck with numbers inside.

"It's called Shuffleboard," he said, setting up the game.

Inside the triangle were the numbers seven, eight, and ten, and farther back was a negative ten, which meant if you hit it, your score would go down. The goal was to push the disk across the deck and land it inside the other triangle.

I wasn't very good at it.

No matter how hard I tried, I could only get the disk halfway across the board. Peter, on the other hand, made it every time. He was very good. At the end of the first game, the score was thirty-three to zero. I was the zero.

We played two more rounds, but I gave up after that and sat down on a bench near the rail. My hands were tired, and I didn't like losing.

Peter sat beside me. He put his arm around my shoulder.

I tensed up and scooted a little farther away.

"Josephine," he said, inching closer, "you don't have to be shy. I wouldn't hurt you."

He slid off the bench and knelt down so our eyes met. I hadn't noticed, but at some point, he'd placed his hand on my lap.

"I need to grab something from my cabin," he said softly. "Why don't you come with me? It'll only take a minute. After that, we can play something different."

I hesitated. But I nodded.

We walked down the hall toward the cabins. As we went, I noticed a tattoo on his shoulder.

"Do you like doughnuts?" I asked suddenly.

Peter laughed. "Of course I do. Why?"

I pointed. "Your tattoo—it looks like one."

He chuckled. "Oh, that old thing."

A moment later, we reached a door marked E–36.

"Wow," I said, reading the number. "Your room's really close to ours."

"I know," he said quickly.

I blinked. "Wait... how do you know where we're staying?"

He didn't answer. Instead, he opened the door and stepped inside. I followed.

The room looked a lot like ours. Small, with a washbasin and a single bed. But something was different.

I noticed it right away.

Ladies' clothes.

They were folded on the dresser. A skirt. A blouse. A pair of shoes that clearly weren't his.

"Wait..." I said slowly. "Why are there so many women's clothes in here?"

Peter paused. "That's, uh... my wife's. Her clothes."

He tried to smile. "Why don't you sit on the bed while I find what I came for?"

I walked to the edge of the bed. But something felt off.

The bed looked far too small for two people. I turned back—and he was standing much too close behind me.

Then, without a word, he pushed me down.

"You'd better not tell anyone!" he hissed.

I stared up at him, frozen. My heart was pounding.

"Tell who?" I cried. "Is this even your room?!"

I started to scream.

And just then, the door flew open.

A woman stood in the doorway, staring.

Peter turned, stunned.

"Who are you?" she yelled. "And why are you in my room?!"

Peter didn't answer. He just shoved past her and ran—bolting down the corridor as fast as he could.

I stayed on the bed, shaking, my hands clenched in my skirt.

The woman turned to me, her face softening. "Sweetheart," she whispered. "Are you all right?"

I couldn't answer. I was crying too hard.

Date:Thursday, the Eleventh Day of April, 1912

Place:Titanic– Cabin E–36

Time:Thirty-eight Minutes Past Four in the Afternoon

The ship's officers arrived quickly—especially with a child involved.

Mama and Papa were notified immediately and rushed over as fast as they could. They didn't have far to come, since our cabin wasn't far from where I'd been found. Anneliese was with them, clinging to Mama's side.

I was still sitting on the bed, trying not to cry, while a ship's doctor gently examined me and asked quiet questions. My hands were shaking.

One of the ship's younger officers entered the room. He was in uniform, with a calm but serious face.

"Good afternoon, miss. I'm Fourth Officer Joseph Boxhall," he said gently, crouching a little to be closer to my height. "I know this is difficult, but can you try to tell me what happened?"

I nodded slowly.

"I... I thought he was nice," I began, voice trembling. "We played shuffleboard out on the deck."

I paused to wipe my eyes.

"Then he said he needed to get something from his cabin. I followed him, but... it wasn't his room. It was hers." I pointed to the woman standing in the doorway, her face pale and serious.

"Please, go on," Boxhall said quietly.

"He told me to sit on the bed," I said. "Said he had to find something before we went out to play a different game. Then he just... pushed me down and yelled at me."

My voice broke again as I began sobbing.

"That's when I walked in," the woman said firmly. "He was in my room—Cabin E–36. I saw him standing over her, looking angry."

Boxhall turned to her. "Can you describe him?"

"He had a mustache," she said. "That much I saw before he ran."

"He had a tattoo too," I added, sniffing. "On his left shoulder. It looked like... a doughnut."

Boxhall gave a quiet nod, then rose to his feet.

Just then, several more officers arrived at the door—Fifth Officer Harold Lowe, Third Officer Herbert Pitman, Sixth Officer James Moody, and Second Officer Charles Lightoller.

"Perfect timing, gentlemen," Boxhall said briskly.

"Lowe and Pitman," he continued, "I want you two to check the Promenade Deck and any outer walkways. Look for a man with a mustache and a tattoo on his left shoulder—a doughnut, the girl says. Approach with caution. Do not confront him alone."

The two nodded and stepped out at once.

"Moody, Lightoller," Boxhall turned to the others. "Search the second-class common areas, smoking lounges, and hallways. We need all eyes on this."

The officers moved with quiet urgency.

"You'll be alright," the doctor told me softly. "You weren't injured, thank goodness. But I recommend you stay with your family—or at least in a group—until this man is found."

"And we will find him," Boxhall said, turning back to me. "I give you my word."

He then turned to the woman who had found me—Miss Mabel, as her name was written on the passenger list hanging by her door.

"As for you, Miss Mabel," Boxhall said firmly, "I advise you keep your door locked from now on."

"Oh, believe me," she said, her voice shaking just a little. "I will."

TITANIC -4

Author:

Audience Rating:

Publication:

Genre:

Character Age:

Other Keywords:

Permission:

Keeping Together

When we returned to our cabin, Mama looked me over carefully, checking to see if I had any bruises. I didn't—but I was still scared.

I had thought Peter was a nice man. But he yelled at me, pushed me onto the bed, and hurt my feelings. Now... I just don't know what to think.

I have so many questions—questions I don't think I'll ever get answers to.

One of them is: why was he in that lady's cabin?

The rest of the evening was quiet. The sun was still shining, and I wanted to go back outside to play. But Papa told me I wasn't allowed to go out on the deck alone anymore. Anneliese had to be with me at all times.

"Just because I'm the youngest doesn't mean they have to treat me like a baby," I grumbled, sitting on my bed with a pout.

"You're acting like a baby," Anneliese giggled.

I stuck out my tongue at her.

"You two stop that," Papa scolded.

"I'm bored," I whined. "Can't I at least go to the library and get the book I was reading earlier?"

"I really don't want you out there right now," Papa said firmly. "Not with that man still on the loose."

"Okay," I mumbled, arms folded.

As usual, Anneliese was playing jacks. I sat down beside her on the floor to join in, but before long, I drifted off to sleep right in the middle of the game.

When I woke up, Anneliese was helping Mama with something near the washbasin. I felt a little left out—not angry, just... sad that I wasn't part of whatever they were doing.

When supper time came, we all left the cabin together. I felt like I was being punished—even though I hadn't done anything wrong. I walked slowly, keeping my eyes on the floor the entire way to the dining room.

As we walked, I kept hearing little noises—soft sounds coming from behind the walls or down the hall. I tried not to think too much about it. It was probably just other passengers leaving their rooms, I told myself.

When we reached the dining room, I noticed an officer standing near the entrance, watching the passengers as they filed in. He didn't speak, but he was keeping a careful eye on the men entering the room.

I figured they were doing this because, sooner or later, Peter would have to show up.

He has to eat sometime...

~o~O~o~

I still felt sad about losing what I thought was a friend.

He was almost like a grandpapa to me. He must've been around forty or fifty years old, but he had been kind—at least at first. He was a nice man... or so I thought.

I kind of wished he hadn't turned out to be a bad person.

I had fun playing shuffleboard with him, even though I lost every time.

Yes, he was a bit strange, especially when he put his hand on my shoulder. But at the time... it hadn't hurt. Not physically.

I lay down on my bed and let out a long sigh.

Mama must have heard me, because a moment later, I felt her presence beside me.

"What's wrong, sweetheart?" she asked gently.

"Nothing," I sighed again, not meeting her eyes.

"I know something's wrong," she said, sitting down next to me. "You always sigh like that when something's hurting on the inside."

I sat up slowly and rested my head against her shoulder. "It's Peter," I murmured.

"Peter?" Mama asked.

"He's the man I met earlier," I said quietly, barely above a whisper.

Mama's expression changed. "Josephine, he's not a good man," she said, sharper now. "He nearly hurt you. And he got you into trouble. You shouldn't have gone into that room with him. He could've done something much worse."

Her voice shook a little. I started crying.

"Oh, baby..." Mama wrapped her arms around me and held me close. "Why don't you try to sleep now, hmm? Things always look better in the morning."

"I hope so," I whispered through a yawn.

I lay back down, and Mama pulled the blanket over me. She walked over to check on Anneliese, already fast asleep in the top bunk.

"Momma?" I called softly.

"Yes, dear?" she asked, looking down at me.

"I'm sorry," I whispered, eyes heavy.

She gave me a soft smile, and before I could hear her reply, I was already asleep.

Date:Friday, the Twelfth Day of April, 1912

Place: Titanic – Family Cabin

Time: Fourteen Minutes Past Ten in the Morning

The next morning, just after we returned from breakfast, there was a knock at our cabin door.

It was Officer Boxhall.

He stepped inside and removed his cap. "We've caught him," he said quietly.

Peter.

Except... that wasn't his real name.

"He was hiding in third class," Boxhall explained. "Moving between empty cabins. A night watchman spotted him trying to break into the kitchen to steal food."

Papa clenched his fists, standing protectively near Mama.

Boxhall continued. "His real name isn't Peter Goodman. It's Francis Hermann—a former reverend from Salt Lake City, Utah."

The name didn't mean anything to me—but the look on Mama's face said enough.

"He's wanted in connection to the murders of two women from his congregation," Boxhall added grimly. "And he's also suspected of killing his ex-wives... and two of his own children."

My stomach turned.

"He's in custody now," Boxhall finished. "Locked in a secured room below until we reach America."

None of us spoke for a moment.

The cabin felt smaller. The air felt heavier.

All I could think was:

He wasn't just a bad man. He was something worse.

And I had followed him. Smiled at him. Played games with him.

I didn't say anything out loud.

I just sat down on my bed, and hugged my doll tight.

Date: Friday, the Twelfth Day of April, 1912

Place: Titanic – Second-Class Promenade / First-Class Deck

Time: Just after Ten in the Morning

Even with Francis in custody, I still wasn't allowed out of the cabin alone. Anneliese was, though—she was tired of being cooped up. We ended up going outside to the shuffleboard court.

"This is the same one Peter and I played at!" I cheered.

"You mean Francis," Anneliese corrected me.

"He was Peter when we played here," I said, trying not to cry.

"Let's not play this game," Anneliese muttered, staring down at the deck. "It gives me the creeps... knowing a murderer was standing here."

I was disappointed, but I nodded and walked on to find something else to do. As we strolled along the deck, we saw the two children from the other day—Marjorie and Marshall—playing Deck Quoits again.

"Hello!" I called to them.

"Oh, hi!" Marjorie waved. "Want to play with us?"

"Not really," I said as I came closer. "I'd rather watch."

"Suit yourself," Marjorie said with a smile. "What about you?" she asked Anneliese.

"I guess," Anneliese replied with a shrug.

While I watched them play, I overheard two men walking by. Their voices were low, but not kind.

"What's this garbage doing on board?" one of them growled, looking at the lifeboats lined along the deck. "What a waste of space on a ship that's unsinkable."

"I agree," said the other man. "Not even God Himself could sink this ship."

They laughed and continued walking.

Something about that line made me feel uneasy.

I decided to follow them. Anneliese was too busy playing to notice, and I thought I'd be back before she even realized I was gone.

I trailed the men across the deck, keeping a safe distance. They talked nonsense the entire time—boasting, sneering, bragging about money and politics. Eventually, I realized we'd gone quite far... and I hadn't been paying attention to where we were.

Suddenly, a man's voice shouted from behind me.

"Hey! You there—kid!"

I froze. A crewman was running toward me.

The two men I'd followed looked back at me, laughed, and kept walking.

"What are you doing on the First-Class Promenade?" the crewman demanded.

"The what?" I said, looking around in confusion.

"Come with me, young lady," he said, reaching for my arm.

"You don't have to do that," another voice interrupted gently.

The crewman turned—and his eyes widened.

"Captain Smith... sir!"

"I'll handle this one," Captain Smith said calmly.

The crewman nodded stiffly, released me, and hurried back to his post.

Captain Smith looked down at me with kind eyes. "So," he said, "you're the young lady who helped capture a criminal."

"

"What?" I gasped. "How do you know about that?"

"Come with me," he said with a smile, resting his hand gently on my shoulder as we walked. "Word travels fast on a ship. You became something of a hero, you know. That man's been running from the law for over fifteen years."

"But Peter was such a nice man," I whispered.

"Is that what he called himself?" Captain Smith asked.

"Yes," I replied. "Peter Good Man—" I paused, then added, "Goodmann."

The captain laughed. "He cleared his throat when he said it, didn't he?"

"Yes!" I giggled. "Every time!"

As we walked along the first-class deck, I spotted Mama, Papa, and Anneliese searching for me near the staircase.

"There's my family!" I said, pointing. We headed down to them.

Papa scolded me right away for leaving Anneliese behind—but then he looked up and saw who I was with.

"Captain Smith," he said, nearly stammering.

"Please," the captain chuckled, "call me Edward Smith."

"We're terribly sorry for what Josephine has done," Papa said, putting a protective hand on my shoulder.

"Don't be sorry," Captain Smith said warmly. "Why don't your whole family join me for dinner this evening?"

"Dinner... with you?" Mama asked, clearly shocked.

"We'd love to," Papa began, "but... tonight is Shabbat."

"You're Jewish, then?" Captain Smith asked kindly.

Mama nodded.

"Well," he said, "then let's make it a proper Shabbat dinner. I'll have my cooks prepare a traditional Jewish meal—matzo ball soup, baked fish, Challah bread, and Latkes. We can light candles at sunset, if you wish."

Anneliese and I lit up instantly.

"Let's do it, Papa!" we sang in unison.

Papa glanced at Mama, then looked back at us. He thought for a moment.

"...All right," he said. "It's not every day we're invited to dine with the captain of a ship."

Anneliese and I cheered.

TITANIC -5

Author:

Audience Rating:

Publication:

Genre:

Character Age:

Other Keywords:

Permission:

Shabbat Shalom

Date: Friday, the Twelfth Day of April, 1912

Place: Titanic – Family Cabin

Time: Half Past Twelve in the Afternoon

When we returned to our cabin, Mama took me over to the bed.

"I'm disappointed in what you did," she said, sitting down beside me.

"I'm sorry," I whispered, tears in my eyes.

I glanced over at Papa. He had that look—the one that meant he was thinking about spanking me. My heart sank. I didn't want to be in trouble.

"Now, you sit here for a while and be a good girl," Mama said, gently patting my head.

Papa lay down on his bunk. I think he was trying to get some sleep.

I looked across the room at Anneliese. She was sitting quietly, reading a book.

"What are you reading?" I asked her.

"Anne of Green Gables," she said, placing it on the floor so I could see the cover. "It's about an energetic and unusual orphan girl who finds a home with some elderly folks."

"Sounds interesting," I giggled. "I was reading a book called Moby-Dick."

"Oh! The story about the great white whale that Captain Ahab wants revenge on?" She laughed.

"Yes!" I squealed.

"I have it right here," she said, handing me the book.

"Wait—how did you know I was reading this?" I asked, surprised.

"Someone up in the library gave it to me," she laughed. "They thought I was you and said I should keep reading it. I figured they meant you, so I brought it back."

"Thank you!" I cried. "I was reading this before... before I spent time with Peter."

"You're welcome," she said softly. Then, more serious: "Next time, don't be foolish and follow strange grown-ups."

I looked down at my feet. "I won't," I sighed.

I curled up on the bed and opened the book. The words felt familiar, like returning to a place I hadn't visited in years—even though it had only been days.

I read a few chapters, but before long, my eyes started to close.

I was pooped, as Mama would say.

~o~O~o~

Papa and I woke up a few hours later—just as someone knocked at our door.

Papa opened it, and to our surprise, Captain Smith stood in the hallway, holding two beautiful dresses draped over his arms.

"I thought your young ladies might like something special for this evening," he said with a smile, handing the dresses to Papa.

Anneliese and I jumped up right away, eyes sparkling with excitement.

"Are you sure about this?" Mama asked.

"You're our guests," Captain Smith said warmly. "And it wouldn't be proper for two young ladies to attend dinner without looking their best."

"Thanks!" I said cheerfully. Then I paused and looked at Mama and Papa. "But what about them?"

"Oh, don't worry," Papa said. "We'll find something to wear."

"Nonsense," the captain replied. "Come with me. I'll have my steward help you both. And my maid will come assist the girls."

Mama and Papa left with him, and a few minutes later, a well-dressed woman entered the room. She had a neat uniform and a calm, practiced smile.

"Alright then," she said kindly. "Why don't we get you ready? Would you like help with your dress?"

"No thank you," I replied politely. "I can do it myself."

"It's quite alright," she said, stepping closer. "I help girls with this sort of thing every day."

She gently reached for the ties of my old dress. I hesitated, suddenly nervous. My hands moved instinctively to protect myself—without thinking.

The maid paused. She looked at me for a second... then turned away.

"Oh," she said, her voice suddenly less warm. "I... didn't realize."

"I'm a girl," I said quietly, but firmly.

There was a silence.

She didn't say anything cruel—but she didn't smile anymore either.

Anneliese stood up, crossing her arms.

"She is a girl," she said boldly. "Just a different kind. That's allowed."

The maid gave a tight nod, her face stiff. "I'll leave you to it, then," she said quickly, and walked out, shutting the door behind her with a bit more force than needed.

I stood frozen for a moment, my heart beating fast.

Anneliese walked over and squeezed my hand.

"You look great in that dress," she whispered.

I gave her a small smile. "Thank you."

~o~O~o~

When Mama and Papa returned to the cabin, they were dressed in fine clothes—just like the fancy ones Anneliese and I were wearing.

"Where's the maid Captain Smith sent over?" Mama asked.

"Yes, but she felt embarrassed and left," Anneliese said firmly.

Papa looked over at Captain Smith, who didn't look very pleased.

"I'll speak with her myself," the captain said, frowning.

Papa turned toward me. I was sitting on my bed, quietly crying.

"What's wrong, Josephine?" he asked gently.

I looked up at him through tears. "Papa," I sobbed, "I hate... having this part of me. I wish it wasn't there."

Papa sat beside me and wrapped his arms around me. "I know, dear," he said softly.

"Can we... can we have it taken away?" I asked, barely above a whisper.

"Taken away?" Papa blinked, startled. "You mean... like that? You could get hurt."

"I heard some people have had it removed," I said. "Why can't I?"

Papa looked thoughtful. "Josephine... those people had a special kind of surgery. It's not something that can just be done."

I lowered my eyes. "Could I have that surgery someday?"

Papa stood up slowly and walked over to the small round window that looked out over the ocean. He stared out for a long moment, then turned to me.

"Tell you what," he said. "Once we're in America... I'll try to find a doctor who can help. Someone who understands."

My heart leapt. "Really?" I whispered.

"I promise," Papa said with a smile.

"And I'll make sure it happens too," Mama added, stepping forward and placing a gentle hand on my shoulder.

I couldn't help myself—I cheered, spinning around in my new dress, then ran over to Anneliese.

"Did you hear?" I giggled. "I'm going to be just like you!"

Anneliese laughed and hugged me tight.

Date:Friday, the Twelfth Day of April, 1912

Place: Titanic – First-Class Dining Room

Time: Seven O'Clock in the Evening

We were escorted by a crew member to first class. When we entered the dining room, we walked straight over to Captain Smith.

"Shabbat Shalom," Papa and Mama greeted him warmly.

"Shabbat Shalom," Captain Smith replied with a smile. "And Shabbat Shalom to you, little misses," he said, turning to Anneliese and me.

"Shabbat Shalom!" we both said together.

Captain Smith stepped into the center of the dining room.

"Excuse me, everyone," he announced. "For those who wish to join, we're having something special tonight—celebrating Shabbat, the Jewish day of rest, which is similar to what many Christians observe as the Sabbath."

Most of the room quieted. Many people smiled and applauded softly. A few continued their quiet conversations, politely.

Then he turned to us.

"Would you two like to begin?" he asked.

"Us?" Anneliese blinked.

"Yes, you two." He chuckled.

We looked over at Mama and Papa. They were both smiling proudly.

"Go ahead, girls," Papa nodded.

We rose from our seats slowly, a little nervous with all eyes on us. Since this wasn't something we usually did in front of so many people, we felt a little shaky. Still, we walked up to the table where the candles had been placed.

The captain, our parents, and a number of guests watched us closely. Not everyone was interested, and that was okay. But those who did stay were curious—and respectful.

Anneliese took a match and carefully lit the first candle. She handed it to me, and I lit the second one. We waved our hands gently over the flames three times to welcome in Shabbat.

Then we covered our eyes and recited the blessing, joined by those who chose to participate:

"Baruch atahAdonai, Eloheinu melech ha-olam, asher kid'shanu b'mitzvotavv'tzivanu l'hadlik neir shel Shabbat."

We always say it in Hebrew, but what we sang meant:

We always say it in Hebrew, but what we sang meant:

"We praise You,Eternal God, Sovereign of the Universe, who makes us holy withcommandments and commands us to kindle the Sabbath lights."

Next, we lifted our cups—juice for us, wine for the adults—and said:

"Baruch atahAdonai, Eloheinu melech ha-olam, borei p'ri hagafen."

"Wepraise You, Eternal God, Sovereign of the Universe, who creates thefruit of the vine."

Then we uncovered the Challah, the braided bread, and said:

"Baruch atahAdonai, Eloheinu melech ha-olam, hamotzi lechem min ha-aretz."

"Wepraise You, Eternal God, Sovereign of the Universe, who brings forthbread from the earth."

We passed around pieces of Challah for everyone who wished to take part.

To my surprise, more than a dozen Jewish passengers came forward to thank us. They said we did a wonderful job—and we both felt so proud.

"Shabbat Shalom," we told each of them, beaming.

When we sat back down at the captain's table, he leaned over to me and whispered kindly, "I'm sorry about my maid earlier. And just between us—your secret is safe with me."

He gave me a little wink and turned to chat with Papa.

I looked at Anneliese and smiled. She smiled right back.

Supper was served on elegant plates with special utensils that were even marked Kosher. Each one had little words etched into them: Meat, Dairy, or Pareve.

Waiters brought over a buffet, just as the captain had promised. Some first-class passengers chose to have their usual meals from the standard menu, but many tried the Shabbat meal right alongside us.

My favorite part was the Latkes—crispy, golden potato pancakes with onion and matzo meal. Delicious. I also loved the matzo ball soup, though I had my chicken on the side. Anneliese preferred hers together.

Mama had fish, as always. Papa and Captain Smith were deep in conversation at the far end of the table, so I wasn't sure what they were eating—but both looked happy.

TITANIC -6

Author:

Audience Rating:

Publication:

Genre:

Character Age:

Other Keywords:

Permission:

Color me a picture

Date: Saturday, the Thirteenth Day of April, 1912

Place: Titanic – Second-Class Deck

Time: Eleven Forty-Five in the Morning

Breakfast was good today—not quite as fun as last night's supper in first class with Captain Smith, but still pleasant. The best part? We were allowed to keep the fancy dresses the captain gave us. He said they were gifts and refused to take them back. That made Anneliese and me very happy.

Papa and Mama still wouldn't let me wander off on my own. I had to promise—again—that I wouldn't leave Anneliese's side.

We walked around the deck together. There wasn't much to do, but it felt good to be outside in the fresh sea air.

As we passed by a group of women chatting, we overheard one of them mention that the barbershop sold toys. She said it was such a cute idea. Anneliese and I lit up. Toys? That sounded far more exciting than jacks—for once.

We rushed off toward the barbershop.

"Hey girls," a man said as we stepped in. "I'm Arthur White. You here for a haircut?" He had a pair of scissors in his hand. "Snip, snip!" he said, pretending to clip the air.

I stared at the scissors, wide-eyed.

"Uh—" I began, backing up a little.

"No," Anneliese laughed. "We heard you have toys!"

Arthur looked at me and smiled. "I was just teasing. I wouldn't dream of cutting such beautiful hair off two lovely young ladies."

I stopped feeling so tense.

"What kind of toys do you have?" Anneliese asked, stepping forward.

"Just look around," Arthur said. "There are toys everywhere."

We looked around—and our eyes went wide. Toys were hanging from strings, tucked onto shelves, even lined up along the walls. Why didn't we see this sooner?

There were dolls, yo-yos, cup-and-ball toys, and even familiar things like checkers, dominoes, playing cards, and crayons! I giggled when I saw a few more sets of jacks, just like ours.

I wished we could buy all of it.

"How much are the crayons?" I asked, pointing

"How much are the crayons?" I asked, pointing.

"For you?" Arthur smiled. "Just one penny."

"One penny?" I looked confused.

Anneliese leaned over to whisper, "What's a penny?"

"I don't know," I whispered back. Then I looked up at Arthur. "Can we ask our Papa?"

"Of course," he chuckled.

We hurried back to our cabin. But when we got there, Papa was asleep. That disappointed both of us. Mama was sitting nearby on the davenport, knitting something small—probably for the baby she said she hoped to have someday.

"Momma, what's a penny?" I asked.

"A penny is a coin," she said. "Similar to a pfennig back home."

"Back home?" I tilted my head. "You mean where we used to live?"

"It doesn't matter if we don't live there now," Mama said gently. "It's still our home. Always."

"Can we have a penny?" Anneliese asked quickly.

Mama looked puzzled. "Why do you need a penny?"

"To buy crayons at the barbershop," Anneliese explained.

"The barbershop?" Mama laughed.

"They sell toys there!" I added excitedly.

Mama set her knitting down and stood. "Well, why don't we all go see for ourselves?"

Anneliese and I jumped up and clapped.